This post was originally published on this site

Snow covered the storied field of Fenway Park in Boston when Kate Yohay, in the second trimester of her pregnancy, arrived. The ballpark had become a COVID-19 vaccination site, and Yohay was getting her first shot. “That’s going to be a historical moment for me,” she says. “Like what I remember my parents describing as the day they got their polio vaccines.”

Yohay was about as enthusiastic to get the vaccine in early 2021 as one could be. She felt confident in the shots’ development. She was encouraged by the pregnant health care workers who had gotten vaccinated right away and given birth to healthy babies. She did worry whether she would develop a fever afterward and the risk that could pose to her baby. But “it’s still better than getting COVID,” Yohay says. “So for me, it was a small risk, and it was worth the risk.”

Others who’ve been pregnant during the pandemic haven’t been so sure. Cumulatively, only 42.6 percent of pregnant people ages 18 to 49 have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in the United States as of January 15, before or during their pregnancies.

Yet unlike when Yohay rolled up her sleeve almost a year ago, there is now a great deal of data attesting to the safety of COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant individuals and their newborns. “Being vaccinated is one of the best ways that you can keep yourself and your baby safe during this time,” says nurse-scientist Ifeyinwa Asiodu of the University of California, San Francisco.

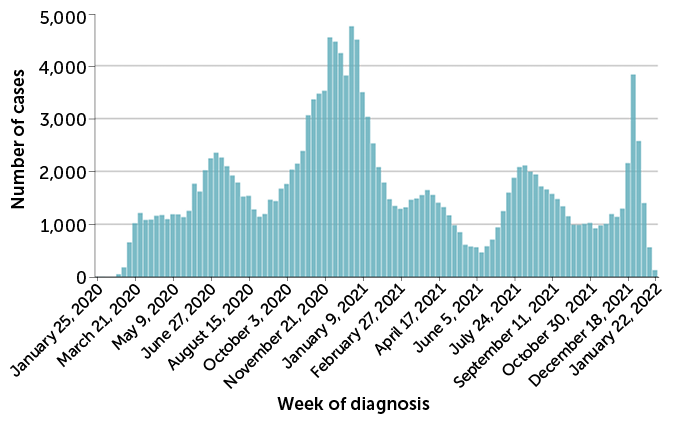

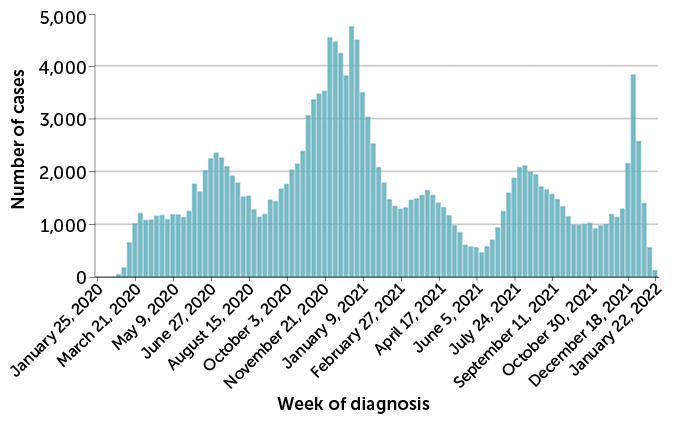

The risks from developing COVID-19 when pregnant and unvaccinated were demonstrated again in a recent study from Scotland. From December 2020 until the end of October 2021, a period when vaccines were available, there were 4,950 confirmed coronavirus infections among pregnant women. Seventy-seven percent occurred in those unvaccinated, along with 91 percent of the 823 hospital stays and all but two of the 104 intensive care admissions, researchers report January 13 in Nature Medicine.

Babies suffered too. The death rate for babies born within 28 days of their mother’s COVID-19 diagnosis was 22.6 deaths per 1,000 births, much higher than the rate for all newborns during the pandemic, 5.6 per 1,000. All of the babies who died over the course of the study were born to women who weren’t vaccinated when they got COVID-19, the researchers found.

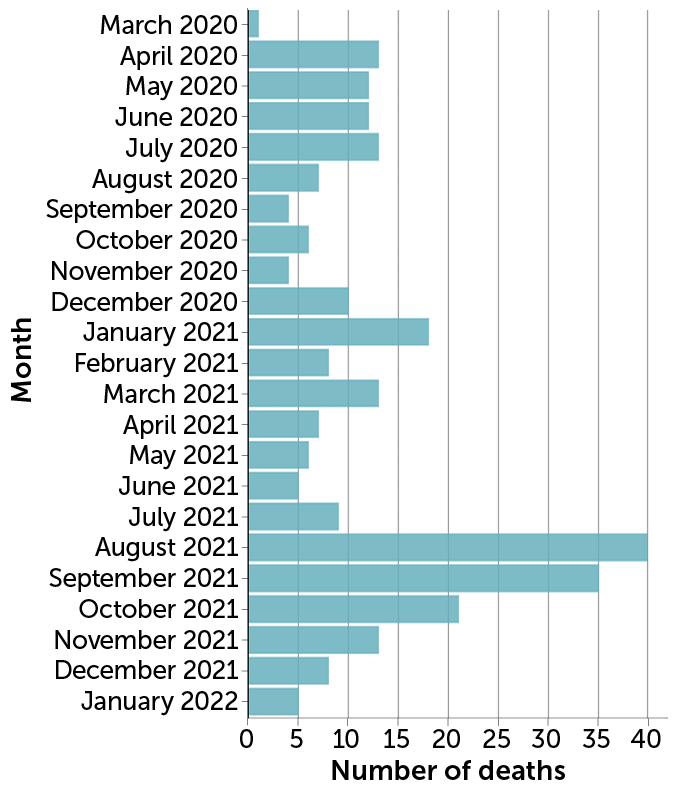

Scientists are still unraveling what’s happening behind the scenes during a SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy, and why the delta variant was especially deadly for those expecting. The highest numbers of U.S. deaths for pregnant individuals, 40 in August and 35 in September, occurred during the delta surge.

There aren’t details yet on how pregnant people fare after becoming ill with the now-dominant omicron variant. But experts don’t advise a wait-and-see approach. And the vaccines continue to offer protection against severe disease and death.

“We’ve all seen terrible outcomes with COVID and pregnancy,” says maternal-fetal medicine specialist Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman of the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. “And we know how preventable some of those outcomes are.”

Tough time for infections

Pregnancy can be a risky time to get an infection in general. Influenza and malaria, for example, can be more severe in people who are pregnant than in those who aren’t.

That risk is tied to changes in the immune system. “Pregnancy is a very complicated immune state,” says Andrea Edlow, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. The immune system needs to defend pregnant individuals and their fetuses against pathogens. But certain immune system players are somewhat suppressed in order to tolerate pregnancy, something that is half self and half non-self.

Plus, the physiological changes during pregnancy can hinder the body’s handling of an infection. “Lots of aspects of your physiology are kind of maxed out,” Edlow says, and “operating at the edge of what your body can do.” For example, the blood clotting system is ramped up to be ready to control bleeding at birth. This already puts pregnant individuals at higher risk for blood clots, which other pathogens, especially SARS-CoV-2, can trigger too.

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was evidence that those infected and pregnant fared worse compared with those infected but not expecting. Pregnant women with COVID-19 were three times as likely to require admission to an intensive care unit and need ventilation, two times as likely to use a heart-lung machine and close to two times as likely to die, researchers reported in November of 2020 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The study included 400,000 U.S. women ages 15 to 44 and covered January to October 2020, before vaccination was available.

An international study of pregnant women covering March 2020 to February 2021 revealed that those with COVID-19 were close to two times as likely to develop preeclampsia — a serious pregnancy complication in which the blood pressure surges and the liver and kidneys don’t work properly — as those who didn’t have the illness. Of the 725 pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19, 59, or 8 percent, developed preeclampsia, compared with 64, or 4 percent, of the 1,459 pregnant women without COVID-19, researchers reported in the September 2021 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

And in a study of pregnant individuals in the United States from March 2020 to September 2021, those with COVID-19 had about two times the risk of stillbirth compared with those who didn’t have the illness, researchers reported in November 2021 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. There were 273 stillbirths among 21,653 deliveries to women with COVID-19, or 1.26 percent, and 7,881 stillbirths among 1.2 million deliveries to women without the disease, or 0.64 percent.

When the delta variant took over in the summer and fall of 2021, the risk of stillbirth grew, the study found. From March 2020 to June 2021, before delta, the risk was 1.5 times higher for pregnant women with COVID-19. From July to September of 2021, when delta reigned, there were 3,559 deliveries among women with COVID-19, of which 96, or 2.7 percent, were stillbirths. Of the 169,330 deliveries among those without the disease, 1,075, or 0.6 percent, were stillbirths. That’s four times the risk.

Some clues have emerged as to why the delta variant raised the stakes. With the original SARS-CoV-2 and the early variants, pregnant individuals rarely had detectable virus in their bloodstream during an infection, Edlow says. It was also uncommon for the placenta to be infected, and even rarer for the virus to spread to the fetus, she says.

But with the delta variant, the amount of virus in the body, or the viral load, is higher during an infection, researchers have found. That, in turn, could increase the risk of the virus spreading to the bloodstream and infecting the placenta, Edlow says.

That occurred in a study of three unvaccinated pregnant women with delta infections and mild cases of COVID-19 in the third trimester. Within two weeks of their diagnoses, two of the women had stillbirths, and the third woman’s baby had to be delivered early by emergency cesarean surgery. The two women who had blood samples taken at delivery had bloodstream infections, and all three women had infected placentas. The organs showed signs of SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, Edlow and her colleagues report January 13 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases. This inflammatory condition damages the placenta and endangers the fetus.

A shot good for two

The first inklings that COVID-19 was especially dangerous for pregnant people came in the first year of the pandemic. Year two brought vaccines and plenty of research that found COVID-19 vaccination was safe during pregnancy.

More than 194,000 pregnant people in the United States have gotten COVID-19 vaccines as of January 31, according to the CDC. There have been no reported safety concerns. A study of close to 2,500 participants in a CDC COVID-19 pregnancy registry found no increased risk of miscarriage after vaccination, researchers reported in October of 2021 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Nor is there a risk of the baby coming too soon or too small, researchers report January 7 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The U.S. study of over 40,000 pregnant women found no link between COVID-19 vaccination and preterm birth (a birth before 37 weeks) or small-for-gestational age, when a newborn’s birth weight is on the lowest end of the spectrum.

In contrast, “preterm birth, stillbirth, adverse pregnancy outcomes, maternal risk, all have been definitively linked to having COVID,” Edlow says.

As for post-vaccination reactions, a study of over 17,000 people who were pregnant, nursing or planning pregnancy found that most reported pain at the site of the shot, while close to a third felt fatigue. Study participants who were pregnant were less likely to report a fever than those who were planning pregnancy, the researchers reported in August of 2021 in JAMA Network Open.

Among participants who were nursing, 339 of 6,815 after the first vaccine dose and 434 of 6,056 after the second dose reported a drop in their milk supply that lasted less than 24 hours.

Getting vaccinated against COVID-19 when pregnant also appears to protect the baby, as the post-shot antibodies can cross the placenta. For example, a study from November of 2021 analyzed umbilical cord blood from 36 pregnancies during which the moms had gotten shots. All of the newborns had high levels of antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (the protein the vaccines target), researchers reported in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

And the antibodies are also found in the breastmilk of those vaccinated while nursing, several studies have found. These antibodies can be passed along to the nursing infant, researchers report in the February Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Confidence and doubts

Even with the reassuring data on COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy, it’s been hard to stamp out the uncertainty some feel about the shots. Other vaccines are routinely recommended in pregnancy, such as the influenza shot. But the COVID-19 vaccines were new, and pregnant people — as is standard practice — were excluded from the clinical trials that assessed the shots’ safety and efficacy (SN: 5/30/18).

Initially, there wasn’t strong guidance on getting the shots during pregnancy. That left pregnant people wondering, “Is this safe? Is this something I should do now, or should I wait until after I give birth?” Asiodu says.

Excluding pregnant women from the trials can make it seem like “something must be wrong, this must be dangerous,” Edlow says. There were no safety issues among individuals who became pregnant during the trials, nor were there safety concerns in animal studies. Medical organizations said that COVID-19 vaccines shouldn’t be withheld due to pregnancy, but a forceful recommendation for vaccination didn’t come until July of 2021.

There are also structural barriers to more widespread vaccination, which impact pregnant individuals too, says Asiodu. And these barriers do not impede all equally. Hispanic and Black people are less likely to have access to paid family leave than white people. Having to save days for after birth, or for prenatal appointments, makes it even harder to take time from work to get vaccinated. These issues need structural solutions, Asiodu says.

Increasing vaccination among pregnant people also “takes listening,” Asiodu says, “hearing what their concerns are, and really addressing them.” And meeting people where they are, Edlow says. “When pregnant people aren’t getting the vaccine, it’s not because they want to be sick. They think they’re doing the best thing for their baby.”

Plus, pregnant people can be bombarded by relatives and friends skeptical of vaccination. The scrutiny that those expecting face, and the relentless opinions offered about their and their babies’ health, can shake even the resolute.

Caroline Fiore of Lincoln, Mass., knows what that’s like. She was vaccinated against COVID-19 before she became pregnant in the summer of 2021. When boosters were recommended, Fiore didn’t hesitate to sign up. She got her third dose during the second trimester of her pregnancy, in November.

“I was taken aback by how monumental that decision felt when I was sitting in the chair” at her appointment, Fiore says. It felt emotional and powerful to do something that directly benefitted her and her baby. But she was surprised to feel some fear too.

She has family members who chose not to be vaccinated, including a relative who shunned the shots while pregnant. Their views “never changed my mind,” Fiore says, but played into an anxiety response of “well, what if I’m wrong.”

Fiore had to let go of “any judgment or discomfort around anybody else’s response” to her vaccination, she says. She has no regrets. “After the vaccine dose, you feel a little superhuman, so I’m still kind of riding that wave.”