This post was originally published on this site

Rosalind Franklin’s role in the discovery of the structure of DNA may have been different than previously believed. Franklin wasn’t the victim of data theft at the hands of James Watson and Francis Crick, say biographers of the famous duo. Instead, she collaborated and shared data with Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins.

Seventy years ago, a trio of scientific papers announcing the discovery of DNA’s double helix was published. Watson, Crick and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1962 for the finding. Franklin, a chemist and X-ray crystallographer, died of ovarian cancer before the prize was awarded and was not eligible to be included.

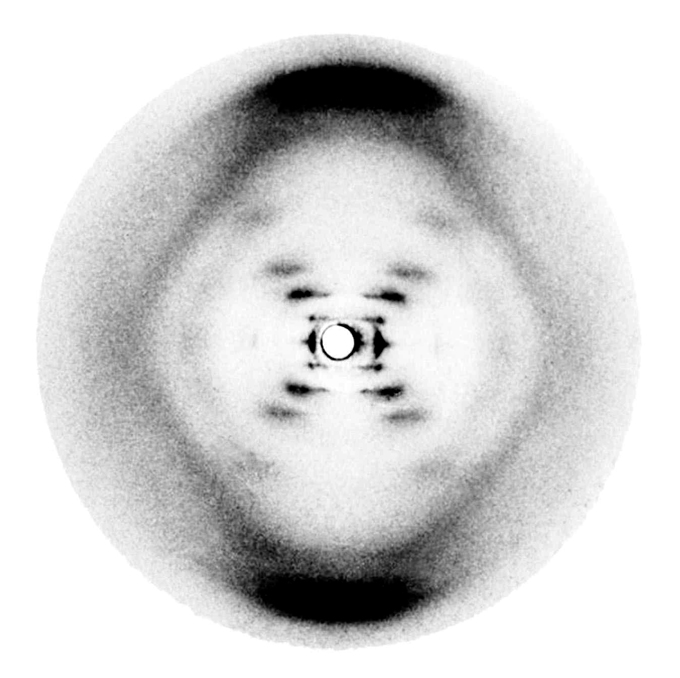

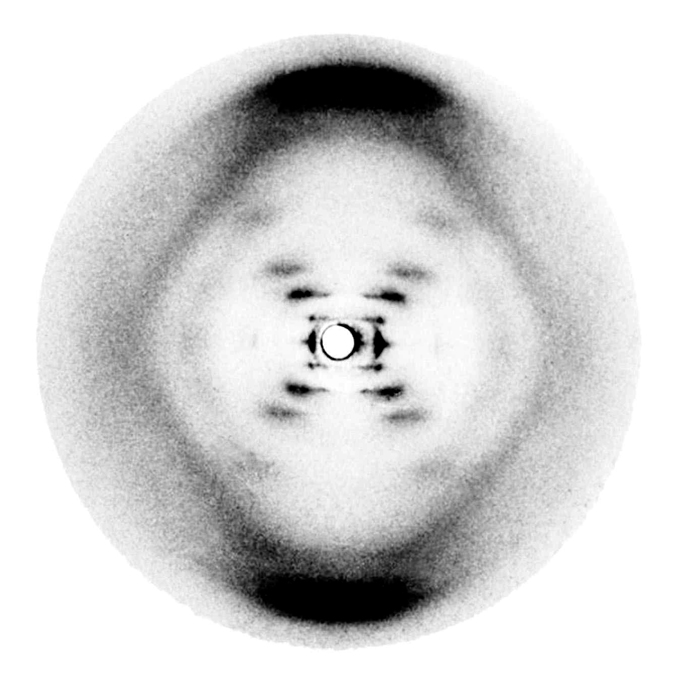

Many people have been outraged by accounts that Watson and Crick used Franklin’s unpublished data without her knowledge or consent in making their model of DNA’s molecular structure. What’s more, Franklin supposedly did not understand the significance of an X-ray diffraction image, taken by her graduate student, that came to be known as Photograph 51. Wilkins showed the image to Watson, who is said to have instantly recognized it as proof that DNA forms a double helix. And the rest is history.

Except that history is wrong, say Watson and Crick biographers Nathaniel Comfort and Matthew Cobb. Cobb is a zoologist at the University of Manchester in England, and Comfort, of Johns Hopkins University, is a historian of science and medicine. They uncovered historical documents among Franklin’s papers that they say should change the view of her contribution to the discovery.

Among the documents was an unpublished article from Time magazine depicting Watson and Crick as a team collaborating with Franklin and Wilkins, who were working as a pair. Overlooked letters and a program from a presentation to the United Kingdom’s Royal Society reinforced the idea that Franklin was a willing colleague who understood her data. The researchers laid out their findings in a commentary in the April 27 Nature.

Cobb and Comfort talked with Science News about their new view of Franklin’s contributions. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

SN: Why did you decide to go through these documents?

Comfort: Matthew’s writing this biography of Crick, and I am writing a biography of Watson…. And we decided as a kind of pilgrimage to go and see the Franklin papers in person….

We weren’t expecting really anything other than just sort of a perfunctory visit when we sat down in this archive room together, and they pulled out the folders. We started going over them together, bouncing ideas back and forth saying, “Hey, what’s this?”

The sparks started flying, and that was when we found this magazine article from Time that was never published. It was a very rough draft that the author, named Joan Bruce, had sent to Franklin for fact-checking to make sure she got the science right.

Cobb: So what Nathaniel immediately picked up on in the Bruce article was the way that she presented the discovery. She presents it as being an equal piece of work — that the two groups, at King’s [College with Franklin and Wilkins] and at the Cavendish [Laboratory with Watson and Crick] in Cambridge, are effectively collaborating….

It’s not [the story] we’re used to hearing because the version we have is the dramatic Jim Watson version from his book The Double Helix: “Ha-ha! I stole their data!… Little did they know but I had it in my hands.” This is dramatic reconstruction.

Comfort: If it were this way [as in Bruce’s article], it actually gives the lie to Watson’s sensational account. And we know why — or at least I think I know why — Watson gave that sensational account.

The audience for The Double Helix was intended to be high school and college students who he wanted to get excited about science.… And I have lots of examples from that book where he stretches the truth, where he takes liberties, where he takes literary license. And I can show that as a pattern through the entire book. So it also fits with the style and tone of The Double Helix.

SN: Is there other evidence that Watson and Crick didn’t steal her data?

Cobb: What we have separately done by looking in real detail at the records — the interviews that Crick did in the ’60s and so on — is we’ve been able to reconstruct the process that [Watson and Crick] went through. Which, if you read their papers really carefully, actually says quite explicitly that they engaged in what they called a process of trial and error. So they knew roughly the size of the crystal of the DNA molecule. They knew the atoms that should be in there from the density. So they tried to fit this stuff into this size using chemical rules.

Then there’s this report [on X-ray diffraction data] that was written by the King’s researchers, Franklin and Wilkins, as part of their funding from the Medical Research Council. It was shared with other laboratories, including the head of the laboratory in Cambridge, Max Perutz [Crick’s boss]. And this is all known, so we haven’t discovered this. Watson and Crick used some of the numbers in there from Franklin and Wilkins as a kind of check on their random walk-through of possible structures….

This still looks like kind of underhand, right? Because they’ve been given this semi-official document. Then two things happened. Firstly, if you read their documents, it’s quite clear that they do explain that they had access to this document, and that they used it as a check on their models. So this fact is acknowledged at the time….

We then stumbled upon a letter from a Ph.D. student who was at King’s College, called Pauline Cowan, who was a friend of Crick’s…. So Cowan writes this letter asking him for help with something completely uninteresting. Then she says in passing, “Franklin and Gosling” — that’s Franklin’s Ph.D. student who took Photograph 51 — “are giving a seminar on their data.” This is in January 1953. “You can come along if you want. Here’s the details. But they say that they’re not really going to go into much detail. It’s for the general lab audience, and Perutz knows all the results anyway. So you might not want to bother coming.”

In other words, Franklin knows that Watson and Crick will have access to this informal report, and she doesn’t care. It’s all, “Hey, if you want it, that’s fine.” So that then shifts the optic away from they got this surreptitious access to this MRC report. So we’re back to this collaborative [picture]. Franklin doesn’t seem to be too bothered.

And then the final element … we found a program of a Royal Society exhibition…. This is two months after the publication of the papers. [In the program] is a brief summary of the structure of DNA signed by everybody, presented by Franklin.

It was like a school science fair. She’s standing there in front of a model explaining it to everybody, and all their names are on it. So this isn’t a race that’s been won by Watson and Crick. I mean, they did get there first, don’t get us wrong. But it wasn’t seen that way at the time. They could not have done it without the data from Franklin. And Wilkins. And everybody — at least at this stage in 1953 — is accepting that and seems okay with it.

Just like the Joan Bruce article said. So this changes the mood, right? We’re moving away from the Hollywood thriller that Watson wrote, where he’s sneaked some data. That version is really exciting. It’s just not true. [We’re moving] to something that’s much more collaborative, modern in some respects, about sharing data.

Today, we focus on Franklin because we’re currently interested in equality, women’s oppression, and so on. We’re also obsessed with DNA. But people weren’t back then. DNA wasn’t then what it is now. [People might think] how could Franklin not have been livid? This was the secret of life and she had had it taken away from her. But it wasn’t and she didn’t.

SN: Did Franklin understand the importance of her data?

Cobb: Franklin was very skilled at being able to move DNA between two forms; what’s called the A form, which is the crystalline form which gives really precise images, and what’s called the B form. That form is what you get if there’s much more water around the molecule kind of pulling it into a different shape. And it was very clear from her notes that she thought that the B form was basically the loss of order, that it was disintegrating….

If you study the double helix story, there’s this this kind of enigma, because there are these two forms, A and B. Franklin studies the A form … [but] it’s never been clear to anybody why she chose that form. And then we realized it’s because she’s a crystallographer. She’s a chemist. And if you’re a chemist, and you’re trying to find the crystalline structure of something, what are you going to look at? The crystal.

It’s easy in retrospect to get in a time machine and go back and whisper in her ear, “Hey, but what’s the inside of the cell like? It’s not very dry, you know. Maybe think about the other form.” But … you can’t do that. That’s against the rules….

Everybody who wants to favor Rosalind Franklin thinks that Watson and Crick were kind of sexist pigs who stole her data. The first bit of that description is probably accurate. The second bit isn’t. They certainly were pretty rude. But they did not steal the data.

This is the popular version of the story which we wanted to undermine. That this Photograph 51, which is the B form, is so striking that Watson, when he’s given a glimpse of it, can instantly realize its significance. According to the story he tells and people who are in favor of Franklin tell, this is the moment he steals her data.

But if you think about it for a minute, you think, “Well, why didn’t Franklin get it if it’s so obvious? This really smart woman who’s much smarter than Watson is about this aspect of science, but she doesn’t get it?” And the answer is very clear when you read her notes. She did get it and she didn’t care. She knew it was some kind of helix, but that was not the structure that interested her.

What [the popular story] does is it removes any agency from Franklin. People are inadvertently presenting her as a negative version, the version that Watson presents. She’s the heroine, but she hasn’t gotten it yet. Why hasn’t she got it? Well, the only implication is what Wilkins says; that she was stubborn and blinkered, which is just not true. So we’re trying to put her back at the center of the story, make her much more human than this harridan that Watson presents her as.

SN: Do we know if Franklin complained at the time about her data being stolen?

So after the double helix [discovery], Franklin and Wilkins never question Watson and Crick, “How did you do this?” They never fall out with them. They never have a row. They never write anything. Either they were stupid and never asked the question, or they knew [that the data were shared fairly].

Then in [19]54, for example, Franklin’s going to the East Coast to go to this meeting on the West Coast that Watson’s going to as well. And so she writes to Watson, “Dear Jim, I gather you’re getting a car across the states. Can I come with you?” So she tried to hitch a ride on a transcontinental car journey with this man who supposedly had stolen life’s secret from under her nose. That doesn’t make sense.

She was on collegial terms — I don’t think she liked him — but she was on collegial terms with Jim…. They had extensive correspondence because they were in the same area of viral structure.

In the last two or three years of her life, she became very good friends with Crick and with his wife. They went on holiday together in Spain after a conference. After she had her first two operations for ovarian cancer, she went to the Cricks to convalesce. She would send Crick her draft articles and ask his advice. So she clearly didn’t think he was a pig who was going to steal all of that data.

SN: So they were just much more chill about the whole thing?

Cobb: They were all much more chill. We look at this, one, through a feminist optic. We being the world. It’s an inverse version of The Double Helix. And, two, through the optic of what would it be like today to discover this? Clearly, you’d have competing labs, they would not talk to each other, and if one of them had these data, then they would behave exactly like Watson describes it.

But that was not the world of the 1950s. Partly because DNA was not DNA. It wasn’t clear that it was the genetic material [of life]. So it wasn’t a big deal.

On Franklin’s tomb there is no mention of DNA. What there is mention of is viruses. Because that’s the practical work that she was engaged in when she died. She had worked out the structure of the polio virus. DNA wasn’t a practical thing for another 20 years. Whereas the structure the polio virus, maybe that could save lives.

The way we see her is not how she was seen at the time. She was very famous. She got a page obituary in Nature, obituaries in Britain’s the Times and the New York Times. So many of her American colleagues were utterly distraught when they discovered that she died [in 1958]. So you know, she was a very significant person, not just for DNA.

SN: Dr. Watson is still living. Have you spoken with him or anyone else who’s still around that could offer some insight?

Comfort: I’ve spoken with him many times, and he knows about this project. But he’s not in any [physical] shape right now to be able to comment on something like this. Believe me, I would love to, but it’s just not possible.