This post was originally published on this site

A sledgehammer dealt the final blow to New York City’s dream of a paleontology museum.

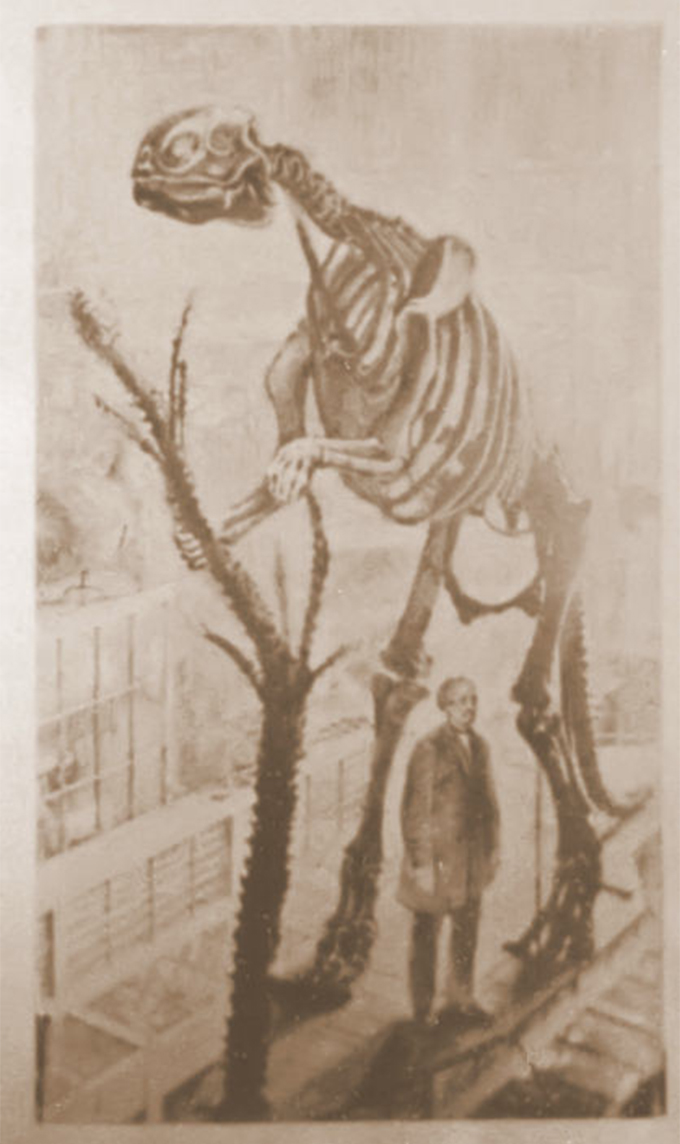

On May 3, 1871, workers broke into the workshop of famed British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Inside, they came upon a plaster skeleton of a towering duck-billed dinosaur — modeled after the first dinosaur fossil unearthed in New Jersey 13 years earlier — alongside a statue of the beast as it would have appeared in life.

These were the first 3-D renderings of any North American dinosaur, a testament to the continent’s geologic past that scientists were only just beginning to understand. But the public would never see the skeleton or the statute.

The workers wrecked the workshop. Plans and drawings were torn to pieces. Sledgehammers shattered the dinosaurs.

In the more than 150 years since, this vandalism has remained one of the most infamous events in paleontology. The story passed down through the years is that the workshop was destroyed on the orders of New York political boss William Tweed in a malicious act of political and religious vengeance.

Tweed viewed dinosaurs as “inconsistent with the doctrines of received religion,” a paleontologist noted later in 1940. The destruction is cited as one of the early battles between a traditional Christian worldview and a growing scientific understanding of Earth’s deep past.

The loss of Hawkins’ dinosaurs has “always been a shock to the paleontological community,” says Vicky Coules, an art historian at the University of Bristol in England. It’s been thought that Tweed “was basically against the whole concept of dinosaurs,” she says.

But the story might be due for a rewrite. Recent historical sleuthing by Coules and her Ph.D. adviser Michael Benton, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol, suggests that the demise of Hawkins’ dinosaurs was not religiously motivated, or even ordered by Tweed.

Instead, the story that paleontologists tell about this affair may say more about the history of anti-evolution sentiment during the 20th century than in the 1800s.

Who was Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins?

Today, dinosaurs are everywhere, the most iconic creatures of the prehistoric past. Their place in the public imagination is in no small part due to Hawkins.

Hawkins dedicated his career to depicting the natural world, even helping Charles Darwin illustrate the 1839 book The Voyage of the Beagle (SN: 1/16/09). In 1854, Hawkins’ most famous artwork went on display when the Crystal Palace reopened in London. Thousands flocked to this showcase of (sometimes looted) wonders from across the British Empire. A natural history section featured life-size statues of dinosaurs made by Hawkins.

This was several years before Darwin published his theory of evolution and only about a decade after the term “dinosaur” had entered the lexicon. For many people, seeing Hawkins’ statues was the first time they had come face-to-face with the concept of deep time (SN: 6/4/19).

Displaying dinosaurs in the flesh was “enormously innovative,” Benton says. “No one had attempted anything like this before.”

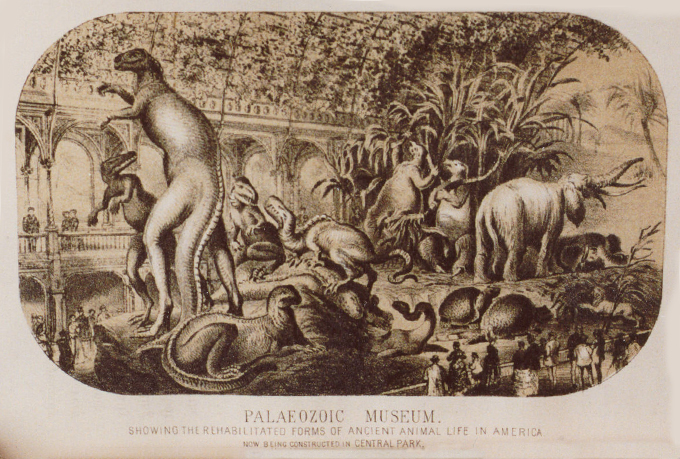

The exhibit made Hawkins the de facto expert on depicting prehistoric life, and in 1868, the Board of Commissioners of Central Park — the group in charge of developing New York’s new green space — asked Hawkins to build similar statues. They were to be the centerpiece for the park’s planned Paleozoic Museum, dedicated to American paleontology.

At this time, most of the major dinosaur discoveries were happening in Europe or its colonies. American scientists had yet to dig into the ample bone grounds of western North America, and most of the continent’s major paleontological finds — including Tyrannosaurs rex — were still at least a decade away (SN: 3/30/23).

But a small number of fossils were starting to come out of the East Coast, including a dinosaur with a flat, beaklike snout named Hadrosaurus found in New Jersey. The Paleozoic Museum, the Central Park commission thought, would give Americans a chance to prove that they too had a prehistory worth remembering. Hawkins’ Crystal Palace statutes “hit [the public] between the eyes,” Benton says. Now, “New York wanted that.”

Hawkins accepted the job. He would dedicate the next few years to a museum that would never open its doors.

The story that paleontologists tell

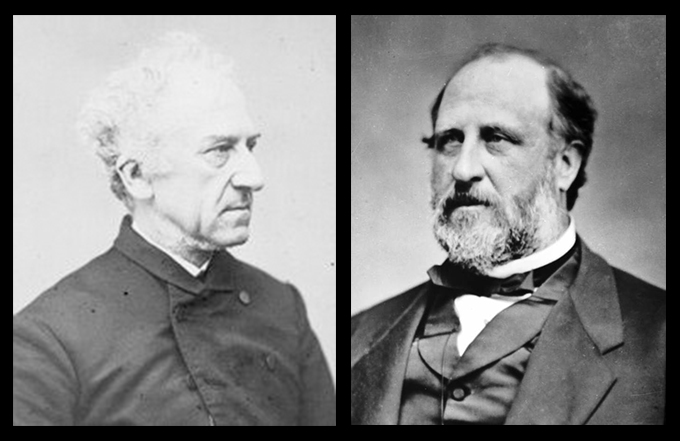

In the 1860s, New York was a city on the rise. One of the men riding that high was William Tweed, a state senator who dominated the city’s political scene. Tweed stripped power from all who opposed him. In May 1870, for instance, he dissolved Central Park’s board of commissioners and created a new group filled with his cronies.

By year’s end, the new commissioners canceled the Paleozoic Museum and moved to discontinue their relationship with Hawkins — without paying him.

The museum’s demise had been simmering in the background for months. Already, Hawkins’ workshop had been relocated from a government building to a shed in the park. The move made room for the growing collection of the upcoming American Museum of Natural History, which, unlike the publicly funded Paleozoic Museum, had the private financial backing of New York’s wealthiest citizens, including the banker J.P. Morgan.

Plans for the two museums coexisted for a while. But eventually, the park commissioners decided that a museum dedicated solely to paleontology and funded by the public was just too big a burden to take on. It didn’t help that at least one member of the park commission was also on the committee for the American Museum of Natural History.

In March 1871, the New York Times — which frequently ran stories critical of Tweed — reported on the loss of the Paleozoic Museum, which Hawkins had lamented at a public meeting.

Two months later, the artist’s dino models lay in pieces.

“Hawkins was distraught,” Coules says. The destruction sent ripples through the scientific community, eventually becoming one of the foundational stories in the history of American paleontology, she says.

And the villain in the story: Tweed.

The Times article allegedly sent Tweed into a rage, and he ordered one of his cronies to descend “upon the Paleozoic Museum with vengeance in his soul,” paleontologists later wrote.

But it wasn’t just the bad press that supposedly angered Tweed. “There was always a rumor that there was some sort of creationist angle to it,” says paleontologist Carl Mehling of the American Museum of Natural History.

This version of the story, which paleontologists have repeated since at least the 1940s, rests on Tweed and his men referring to Hawkins’ dinosaurs as “pre-Adamite” animals and an incident in which one of Tweed’s followers told Hawkins he should focus on living animals. The argument fits into a common perception that emerged during the mid-20th century that religion and prehistory were often at odds in the late 19th century.

This is where the Central Park story begins to unravel.

Rethinking the Central Park dinosaur scandal

Last year while Coules was working on her Ph.D., she read up on Hawkins and things weren’t adding up.

For one, the timing of events didn’t make sense. Why would Tweed wait two months after the Times article to retaliate against Hawkins? When Coules dug up the newspaper story, she found it on Page 5, with no mention of Tweed in the article.

“My first question was, why on Earth would you be upset about that?” Coules recalls.

Tweed had bigger things to worry about. At the time, he had been accused of everything from bribery to money laundering. (Tweed was eventually arrested in late 1871 and died in prison several years later.) So it seemed odd that Tweed, who was fighting for his political life, would take such offense to a story buried so deep in the paper.

Coules started to suspect another culprit: Henry Hilton. Tweed appointed Hilton, a top lawyer to New York’s wealthiest men, to the new board in charge of Central Park in 1870. Hilton took to the role immediately, regularly visiting the park to search for areas of improvement.

Some of these “improvements” were head-scratchers. Hilton had workers paint a bronze statue of the biblical Eve entirely white, permanently damaging the metal. His penchant for destructive whitewashing — he ordered a similar treatment for a whale skeleton destined for a museum — became a joke in the press.

One day while going through her notes at a café, Coules came across park commission meeting minutes from the day before the models were destroyed. In that meeting, the committee resolved to remove Hawkins’ workshop “under the direction of the Treasurer” — Henry Hilton.

“I was like, wow! Look at this!” Coules says. Hawkins himself blamed Hilton for the vandalism. Coules found New York Times articles from the period in which Hawkins implicated Hilton.

But why did Hilton want the dinosaurs destroyed? Coules’ research didn’t pick up any hint that religion was a major motivation. Rather, she argues, Hilton “had a strange relationship with artifacts,” as demonstrated by his whitewashing habits.

Hilton would also go on to harbor other destructive tendencies — swindling a wealthy widow out of her fortune and running her late husband’s business into the ground.

Hilton had “quite strange ideas [that managed] basically to piss off everybody,” says Coules, who published her findings with Benton last year in the Proceedings of the Geologist’s Association.

That Hilton’s “strange ideas” would be behind the Hawkins incident makes sense to Ellinor Mitchel, an evolutionary biologist at the Natural History Museum in London and coauthor of a book on Hawkins’ Crystal Palace dinosaurs. “I think that’s the way of much of history, that it turns it’s sort of out human strengths and weaknesses that pivot the direction of things,” she says.

But not everyone is so sure. “It seemed quite convincing to me that Hilton played an important role,” says Lukas Rieppel, a science historian at Brown University in Providence, R.I., and author of a book on dinosaurs during America’s Gilded Age. But “it’s very hard for historians to know the private motivations of people who died over 100 years ago.”

Still, Coules’ work convincingly shows religion wasn’t a motivating factor.

For one thing, “pre-Adamite” was simply a way to refer to deep time, Benton says. So even if Tweed and Hilton did refer to Hawkins’ models in this way, it would have been more descriptive than derisive. What’s more, natural history — including paleontology — was seen as a respectable, middle-class occupation in the 19th century. “Natural history was seen as an expression of piety,” Rieppel says. “So a way that one could express one’s devotion to God [was] by learning about God’s works in the natural world.”

In fact, the idea that the world was ancient was widely accepted at the time, Benton adds. A more inflexible view of creationism, in which evolution is false and the world is only a few thousand years old, really started to gain steam only in the 20th century, he says.

Religion’s supposed role in the Hawkins’ saga may have been introduced by paleontologists writing about this incident in the mid-20th century, who may have been projecting their experiences with creationist movements into the past, Rieppel says. From there, the story stuck.

Hawkins’ lasting influence

The loss of the Paleozoic Museum might have been for the best. It would have been “obsolete almost immediately and I fear almost comical,” Mehling says — soon overshadowed by bigger discoveries from the American West.

But that doesn’t mean that Hawkins’ models didn’t have value, Mehling says. Dinosaur statues may now be the stuff of tacky roadside attractions and miniature golf courses. But in the 19th century, Hawkins’ statues were key to opening the public’s imagination to an ancient world that was quite different from the present.

Hawkins’ display was so awe-inspiring that in 1905, when the American Museum of Natural History unveiled its 20-meter-long Brontosaurus, it displayed the skeleton upright (SN: 4/7/15).

And Hawkins’ work continues to influence how people think of dinosaurs. While doing research for the Paleozoic Museum, Hawkins strung together the fossil pieces of Hadrosaurus into a standing skeleton and displayed it in Philadelphia. Before this, fossils had only ever been displayed flat on a table or kept in drawers. Visitors flocked to see the strung-together skeleton, overwhelming staff at the institution where it was housed.

The tradition stuck. And today, most museums display their fossils using Hawkins’ method.