This post was originally published on this site

Nola Sullivan recently marked an inauspicious anniversary. A little more than a year ago, on November 16, 2020, the 57-year-old pharmacy technician from Kellogg, Idaho, came down with COVID-19.

“I lost my taste and smell, with a very bad head cold, body aches, muscle spasm, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,” she says. It took a month for her muscle spasms and a lingering headache to go away. She missed nearly three months of work. Her senses of smell and taste still haven’t fully returned. And “I still have the fatigue. It’s horrible. I’m nauseous all the time.”

Sullivan has another lasting reminder of her battle with the coronavirus, too: diabetes.

When she finally returned to work at the pharmacy, “I noticed that I was so thirsty all the time. And I just thought that was part of the COVID,” she says. “I was drinking gallons of water.” As a pharmacy technician, though, she knew that excessive thirst can be sign of diabetes. So she decided to check her blood sugar. A person is considered diabetic when levels of glucose in their blood reach 200 milligrams of glucose per deciliter of blood. Sullivan’s was over 500.

Sullivan is not alone. In a study of more than 3,800 COVID-19 patients, just under half developed high blood sugar levels, including many, like Sullivan, who were not previously diabetic, cardiologist James Lo and colleagues reported November 2 in Cell Metabolism. About 91 percent of the intubated COVID-19 patients had high blood sugar, as did almost 73 percent of people who died of the disease, the researchers reported.

Lo’s group, based at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, and others are now working to identify what’s causing high blood sugar in COVID-19 patients and what to do about it.

Sugar spikes

In March and April of 2020 — months before Sullivan caught COVID-19 — Columbia University Medical Center in New York City was full of COVID-19 patients. There, endocrinologist Utpal Pajvani noticed that “a lot of those people — but not a majority — were coming in with very high blood sugars. For some of those people, this was brand new for them.”

Lo too noticed that many of the COVID-19 patients in his hospital’s intensive care unit had high blood sugar. Preexisting diabetes is a risk factor for poor outcomes from COVID-19. But, like Sullivan, many of the patients Lo and his colleagues were seeing did not have diabetes before they got ill. People sometimes develop diabetes as they age, but Lo’s patients with high blood sugar were often “youngish, in their 30s and 40s,” he says. And levels of glucose in their blood were incredibly high, sometimes more than twice the level that indicates diabetes.

Such sky-high levels of blood sugar were associated with a 15 times higher risk of intubation and 3.6 times higher risk of death compared with people with the disease who had normal blood sugar levels, Lo and colleagues found.

Notes Pajvani, “we don’t know if the high blood sugar is causal of the bad outcome or reflective of the bad outcome.” Still, he and other doctors aren’t totally surprised by the connection between COVID-19 and high blood sugar, or hyperglycemia.

High blood sugar has been documented in people with acute respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, caused by injuries or infections with other viruses or bacteria. ARDS is a condition in which the lungs can’t supply enough oxygen to the body.

COVID-19 patients with ARDS and high blood sugar spent three times longer in the hospital than people with ARDS caused by COVID-19 who have normal blood sugar levels, Lo and colleagues found. But weirdly people with hyperglycemia who had ARDS caused by COVID-19 were less likely to die than hyperglycemic people with ARDS due to other causes.

“The outlook was still bad, just not as bad in the group with ARDS and COVID, which is surprising,” says Ralph DeFronzo, an endocrinologist and chief of the diabetes division at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, who was not involved with Lo’s study.

Fingering a culprit

Exactly what sends blood sugar soaring and causes diabetes in COVID-19 patients has been a mystery. Some evidence has hinted at the coronavirus infecting cells in the pancreas that make insulin, a hormone that lowers blood sugar levels by signaling cells to take in sugar and burn it for fuel. But in Lo’s study, COVID-19 patients with high blood sugar still made high levels of C-peptide, a naturally occurring bit of protein that links two chains of insulin and is made alongside insulin in pancreatic cells. High C-peptide levels indicate that the patients’ pancreatic cells were producing insulin.

These patients’ blood sugar was still high, though. So if the pancreatic cells weren’t the problem, something else must be going wrong.

That something else may be that fat cells infected with the coronavirus send the wrong message to other cells, ultimately leading to diabetes, Lo and colleagues suggest. Lo’s team discovered that COVID-19 patients had low levels of adiponectin, a hormone produced by fat cells that helps other cells heed insulin’s call to take in sugar. People with obesity also often make low levels of adiponectin, possibly explaining why they are at risk for poor outcomes from COVID-19 (SN: 4/22/20). Levels of several other hormones produced by fat cells were also out of whack, the researchers found.

The findings suggest that COVID-19 patients’ high blood sugar levels result from insulin resistance — a condition in which cells ignore insulin’s message to take in glucose — brought on by a dearth of fat hormones rather than by an inability to produce insulin.

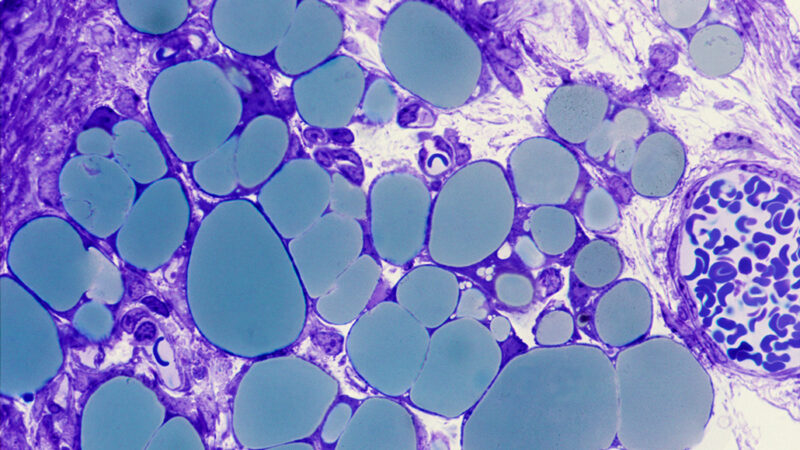

The coronavirus can infect fat cells, the researchers’ experiments with hamsters and with cells grown in lab dishes showed. Damage done to fat cells directly by the virus, or indirectly by inflammation directed toward fighting the virus, may interfere with fat cells’ ability to make normal hormone levels and help maintain steady blood sugar levels.

Experiments by other researchers have also indicated that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can replicate in human fat, also known as adipose tissue, says Jose Aleman, an endocrinologist at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. That’s yet another clue that fat is involved in severe disease.

For instance, autopsies revealed that the coronavirus had infected fat cells of 10 of 18 men who died of COVID-19, researchers in Germany report January 4 in Cell Metabolism. All 10 of the men with coronavirus in their fat were overweight or obese. The researchers also found SARS-CoV-2 in fats cells of 5 of 12 women who died of COVID-19, but those women were not all overweight or obese.

Inspired by Lo’s work, the German team uncovered evidence that coronavirus infection also affects fat cells’ ability to metabolize some lipids, leading people with COVID-19 to develop high levels of triglycerides in their blood. That’s yet another clue that fat isn’t working properly in some COVID patients. And these changes in fat may contribute to more severe COVID-19.

Obesity is often associated with inflammation in fat and other tissues. Coronavirus infection may make that inflammation worse, tipping the scales toward messed-up hormone production and eventual diabetes, Aleman says. Lo’s findings “lend credence to the idea that adipose is the reservoir for this low-grade inflammation that then gets triggered by COVID,” Aleman says.

But the conclusion is not a slam dunk, Pajvani says. “This is an example of very good research done in very difficult settings.” But because the study looked back a group of patients, but didn’t match their characteristics and limit other variables from the beginning, the work can’t definitively show the cause of COVID-related diabetes. “This gives us a great hint of the type of study to do,” he says.

A lasting legacy

Whether coronavirus infections cause diabetes or simply unmask the condition in susceptible people, such as people who are overweight or obese, is not yet clear, DeFronzo says. Aleman agrees. “A lot of these patients have an underlying state of insulin resistance, likely prediabetes, but then acute illness in the form of COVID-19 tips [them] over to diabetes.”

Doctors may be able to counteract high blood sugar by giving COVID-19 patients drugs called thiazolidinediones or glitazones that make cells more sensitive to insulin’s action. DeFronzo says he hopes to test one of those drugs called pioglitazone in COVID-19 patients with high blood sugar. The aim is to prevent the worst outcomes from COVID-19, but patients’ high blood sugar may linger.

For Sullivan, changing her diet and taking medication have helped her to control her blood sugar levels. “I’ve lost almost 60 pounds,” she says. But “they say that the diabetes will probably be for life.”

Trishla Ostwal contributed reporting to this story.