This post was originally published on this site

Calamity after calamity befell Europe at the beginning of the so-called Dark Ages. The Roman Empire collapsed in the late fifth century. Volcanic eruptions in the mid-sixth century blocked out the sun, causing crop failure and famine across the Northern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, the Justinian Plague arrived, killing, by some estimates, nearly half of everybody in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and scores of others elsewhere.

And then, on June 8, 793, a group of marauders attacked a small island off the northeastern coast of Great Britain. As Christian monks noted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, “heathen men destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne island by fierce robbery and slaughter.”

With that description, the Vikings entered the annals of medieval history as merciless raiders, having also killed a local official in southern Great Britain in 789. From today’s perspective, these Norse seafarers burst into existence seemingly out of nowhere.

Exactly when and why the Vikings first turned their boats away from shore to sail south over the horizon and into the unknown is hotly debated. According to some historians, another development in the late eighth century offers a clue: Silver coins known as dirhams made their way to Europe from the Islamic world in the Middle East. Around this time, Viking men in what is now Norway and Sweden became obsessed with silver as a means to purchase brides made scarce by female infanticide, or so a popular theory holds. A desperate need for silver, it was thought, motivated the Vikings’ initial trips across the North and Baltic seas and somehow precipitated their infamous raids.

Other historians, however, suspect the Vikings’ first forays into the outside world long preceded their violent raids and had nothing to do with a quest for silver.

“Our understanding of the chronology of the early Viking Age is really patchy because our best accounts are sometimes written 100 years later,” says Matthew Delvaux, a medieval historian at Princeton University. That includes the description of the Lindisfarne raid in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Fortunately, medieval scholars have recently found another aid to turn to: a solar storm.

Archaeologist Søren Sindbæk and his colleagues at Aarhus University in Denmark have reconstructed the timing of the Vikings’ early voyages by harnessing the power of what was likely a supermassive solar flare that erupted in 775. The flare has helped the team improve radiocarbon dating and thus more precisely date artifacts excavated at Ribe, Denmark, the site of an early medieval trading post.

The chronology of events at Ribe reveals a less violent start for Viking voyages, at least 50 years before the Lindisfarne raid. The secret of Viking success, Sindbæk believes, is best explained by skillful trading, not fearsome raiding.

More precise radiocarbon dating has the potential to reveal other aspects of the medieval world once thought lost to history.

Viking Age archaeology at Ribe

Since the 1970s, archaeologists have been probing Ribe, on the North Sea, for artifacts that could help explain one of the deepest mysteries in medieval history: how, within the span of mere decades, hardscrabble farmers wedged between dangerous seas and impenetrable forests became the Vikings who dominated Europe for nearly 300 years — a period known as the Viking Age.

At some point, a few highly motivated seafarers from the Scandinavian Peninsula made it across the treacherous 100-kilometer Skagerrak strait to Ribe. There, among a cluster of thatched single-story houses on a sandy outcrop rising above a tidal marsh, the Vikings left clues to why they had come.

Sindbæk imagines how Ribe, already a marketplace for settlements to the south, would’ve looked to those early Vikings. “What would impress you at first sight would be all those masts,” he says. “There would be more ships than you’ve ever seen in your life.”

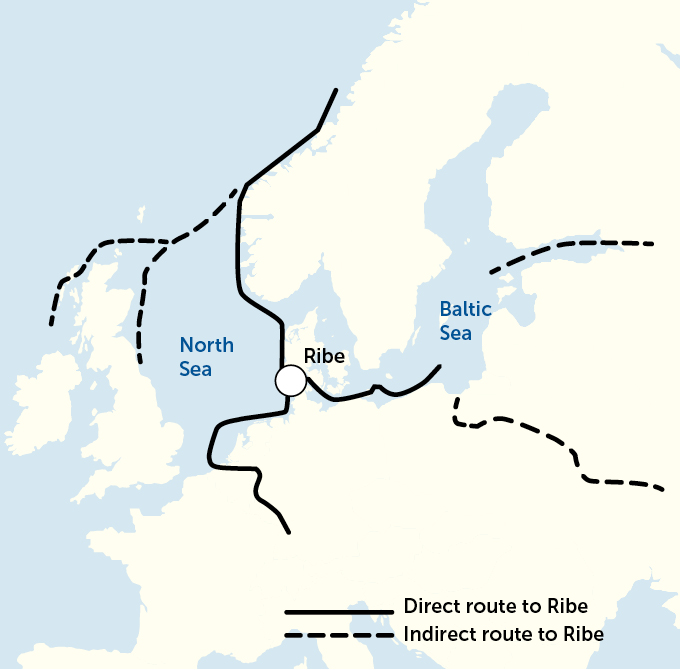

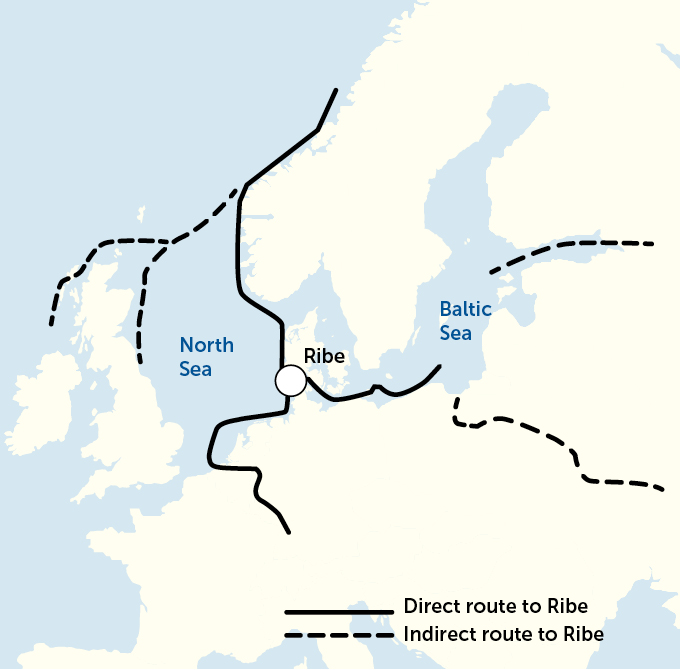

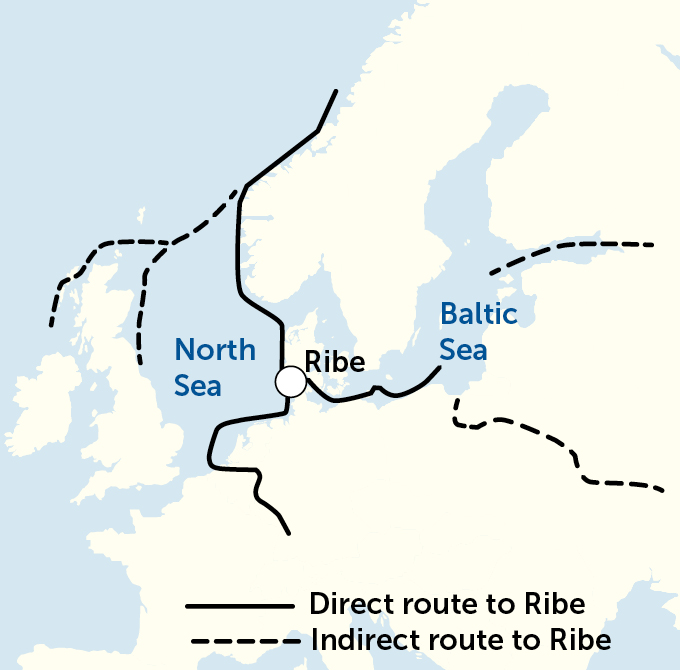

Ribe, Denmark’s oldest town, eventually linked trade routes crisscrossing across northern Europe. The artifacts excavated along its narrow streets reveal when the early Vikings first arrived and where they spread next, expanding their influence around the region.

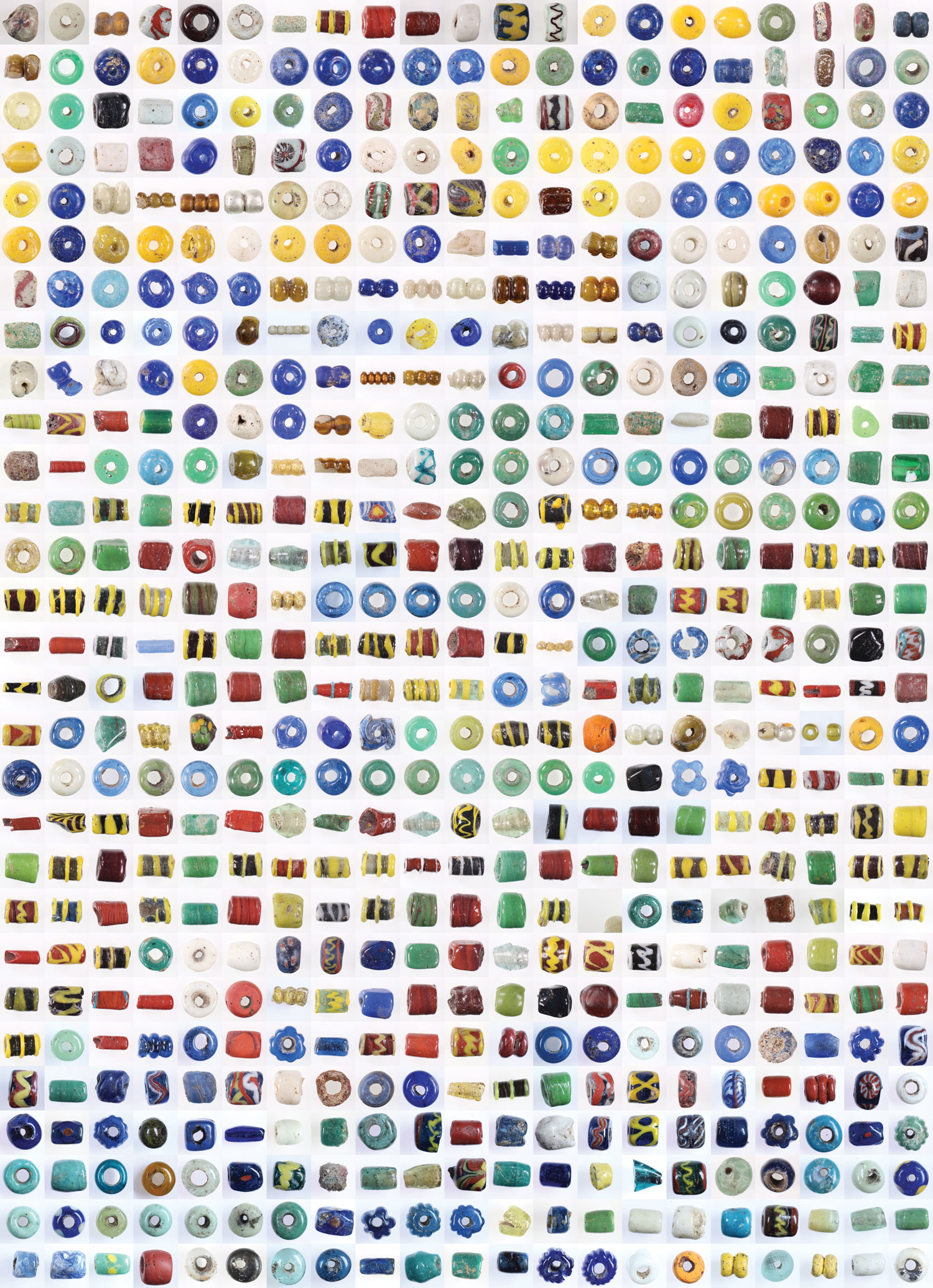

Starting in June 2017 for 15 consecutive months, Sindbæk’s group uncovered extensive evidence of trade in Ribe, starting around the year 700. In clay floors of houses that had functioned as both residences and workshops, the Aarhus team found glass beads, including a kaleidoscopic array of colorful Middle Eastern beads, embedded among debris from prolific metalworking, hide preparation, weaving and bone carving. These were all telltale remains of a Viking Age trading town, where a variety of people met, mingled and hawked their wares.

And they did so peacefully. There is virtually no archeological evidence of violent conflict in Ribe, contrary to the popular myth of Vikings as bloodthirsty barbarians.

“From the beginning Ribe seems to have been a sort of safe haven. You can land here, you’ll be safe. We’re not going to plunder you. We’ll try to outsmart you,” Sindbæk says.

In all, he and his colleagues unearthed more than 100,000 artifacts — tools, accessories and trinkets that would come to define Viking Age culture. In many cases, these objects were made with materials sourced from the Scandinavian Peninsula inhabited by the early Vikings. Some beauties stand out. A magnificent amber battle axe pendant hints at the Vikings’ warrior ethos. Combs carved from reindeer antlers display intricate designs. Terrifying beasts adorn oval brooches. The face of the Viking god Odin graces coins. The artifacts had value beyond their utility or inherent beauty. Back home on the Scandinavian Peninsula, these prestige items gave social status to those who delivered or received them.

“You can kind of show off your ability to participate in these interregional networks the same way that we might show off our ability to purchase a foreign car,” Delvaux says.

Digging down through the centuries, there were many generations of workshops. Twenty shop floors strewn with artifacts. Two hundred years of continuous manufacturing activity compressed into 2½ vertical meters.

Richard Hodges, an archaeologist and past president of the American University of Rome, visited the site in 2018. It’s “a layer cake of superimposed workshops, one on top of another,” he says. “Some burned down. Some of them were just demolished. Every one of them was producing huge amounts of material culture.”

With the layers often bleeding together, the Aarhus team needed to radiocarbon-date each one to put the artifacts in a clear chronological order and reveal the timing of events that produced them.

The limitations of radiocarbon dating

For decades, radiocarbon dating has been a go-to technique for archaeologists. It takes advantage of the fact that when living organisms take in carbon and incorporate it into their tissues, some fraction of the carbon is a radioactive version of the element. It takes 5,730 years for half of that radiocarbon to decay into a form of nitrogen. Knowing that half-life and the amount of radiocarbon in, say, a bone or piece of charcoal helps scientists calculate the age of that organic matter.

But the amount of radiocarbon in the atmosphere — and thus taken up by plants during photosynthesis and then by the animals that eat them — fluctuates over time, so scientists must calibrate their measurements to estimate a true calendar date. Tree rings are handy for this purpose; each one records the atmospheric radiocarbon content in the year it formed. Experts have used trees of known ages from around the world to compile a curve called IntCal20 that plots fluctuations in radiocarbon over the last 55,000 years to help researchers calibrate radiocarbon dates.

But IntCal20’s annual tree ring data are sparse for parts of the eighth and ninth centuries. So archaeologists haven’t been able to date Viking-era artifacts precisely enough to explain the Vikings’ emergence on the global stage.

To fill the gap, physicist Bente Philippsen, a member of the Aarhus team, performed her own calibration using oak tree specimens from the National Museum of Denmark — one of which befittingly had been part of a bridge built by Viking King Harald Bluetooth (the great unifier of people in Denmark and Norway in the 10th century after whom the eponymous device-linking technology is named).

But even with the extra calibration, Philippsen couldn’t narrow the possible age range of a given layer enough to know exactly when Vikings first arrived or when long-distance trading networks reached the town.

An ancient solar flare boosts radiocarbon precision

To zero in on the timing of these events, the Aarhus team looked to see if signs of an ancient solar flare were recorded at the site. In 775, a few literate observers in western Europe reported seeing the impact of a solar storm. Celestial phenomena streaking across the sky were described in various ways: a red cross, inflamed shields, fire from heaven. Some people saw “snakes” slither with the same movements as the aurora borealis.

At the atomic level, solar particles streaming into Earth’s atmosphere kicked off nuclear reactions that transformed some nitrogen atoms into an unstable variant of carbon with six protons and eight neutrons: the isotope carbon-14, or radiocarbon.

Typically, 99 percent of atmospheric carbon is carbon-12, which has six protons and six neutrons. Only one in a trillion atoms of the remaining 1 percent is carbon-14; the rest is carbon-13. But these ratios vary ever-so-slightly over time due to carbon-14’s unstable nature. In 775, the solar storm created 1.2 percent more carbon-14 than usual. That ratio of carbon isotopes became imprinted on any organisms alive at the time.

Physicist Fusa Miyake of Nagoya University in Japan and colleagues first discovered this 775 spike in radiocarbon about a decade ago, in the rings of Japanese cedar trees. Counting the annual rings, she was able to pinpoint the year of the solar storm. It turns out that the sun has on several occasions, about once every millennium and a half or so it appears, sent flares in our direction with enough energy to make measurably more carbon-14.

So while the Aarhus team peeled back layer upon layer of wet clay and sand along one of Ribe’s ancient streets, Philippsen set out to see if any of those layers might date to 775. Up to her elbows in mud and clay at the site, she searched for the right bits of organic material to date.

“I’ve been trained in all the [excavation] methods, so it’s safe for them to let me be in the trench and work, and you get a really good understanding of the samples,” Philippsen says.

Of all the startling finds in Ribe, the site’s trash held the most potential to shed light on the origins of Viking Age trade. Twigs, rye, barley, oats, nutshells and other refuse still lying around more than 1,000 years later possibly bore the time stamp of the supermassive flare.

Philippsen shuttled between her lab at Aarhus and the dig at Ribe with 140 samples plucked from different workshop layers. Trading her trowel for a scalpel, she diced up her bits of ancient oak and ran them along with samples from the site through the lab’s accelerator mass spectrometer, which counts carbon-12 and carbon-14 atoms by sorting them according to mass.

Two pieces of charcoal and a hazelnut shell from a combmaker’s workshop turned out to have the same ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-14 as the oak tree rings dated to 775.

Ribe is a time capsule of early medieval trade

Once Philippsen identified a workshop layer dated to 775, every other workshop and its artifacts above and below fell into a decade-by-decade chronological order. And with that sequence, Sindbæk and colleagues pieced together the evolution of trade at Ribe, reporting the findings in 2022 in Nature.

Around the year 700, ceramics and repurposed Roman glass appear at Ribe, indicating trade with the Franks of the Rhine Valley in what’s now Germany. By the 740s, early Vikings were arriving in ships large enough to carry blocks of Swedish and Norwegian stone. In the 750s, reindeer antler appears from a species not found outside of Norway’s hinterlands — more signs of a Viking presence. Craftspeople in town turned those bulk items into sought-after combs and sharpening stones. In exchange, vendors probably offered the early Vikings beads and brooches that would become the ubiquitous hallmarks of the Viking Age. These items also show up later in other Viking trading towns, such as Birka in Sweden. Finally, around 790, a cache of beautiful beads arrived in Ribe, likely via Russia, indicating new Middle Eastern trade connections.

This scenario strongly suggests, if not proves, that Viking explorations began as regional trading expeditions, not as a desperate bid for Middle Eastern silver, Sindbæk’s team argues.

Given the similar timing, the possibility that the raids somehow relate to Middle Eastern trade goods just then finding their way into northern Europe raises important questions.

“We’re seeing this intensification of [Middle] Eastern trade on the Scandinavian periphery of the North Sea, and that precedes the intensification of Viking raiding in the British Isles,” Delvaux says. “Did this trade stimulate the raids? Were they raiding so they would pick up things to engage in Eastern trade? Did the raids start because people wanted to compete with Eastern trade? I could trade with the Muslims for silver or else I can raid the English for it, right?” Delvaux asks rhetorically.

Regardless, the solar flare clearly demarcates a moment of first contact between emerging civilizations. Sindbæk can imagine how it happened.

The Middle Eastern beads, he says, probably traveled north from the Mesopotamian heartland in several-pound bags before being handed over to a merchant in present-day Turkey, who probably followed nomadic trails north to the forest steppe somewhere in northern Ukraine. There, the merchant may have met Vikings who had come east across the Baltic Sea and exchanged the beads for furs or enslaved people. The beads dispersed through Scandinavian markets, ultimately arriving in Ribe.

Ribe is awash in these imported beads after 790, while the locally made black-and-yellow-striped “wasp beads” individually crafted exclusively in Ribe disappear from the archaeological record. The reason, the Aarhus team concludes, is competition.

Craftspeople living several thousand kilometers away mass-produced beads by dicing up long rods of glass. People now had to ask themselves: “Do I want the beads that are made by Sven on the corner, or do I want the beads Olaf is bringing in from God-knows-where, but he could give me 30 of them for the same price that Sven can make me one?” Delvaux says.

Future questions to address

The solar flare in 775 and a slightly weaker one in 993 with a distinct carbon spike have revealed how Vikings were trying to touch every corner of the globe. Using that 993 solar flare, another group of archaeologists finally confirmed when Vikings lived in North America. Wooden objects at the L’Anse aux Meadows site in Newfoundland, Canada, hold the signature of the 993 flare. Counting tree rings revealed when the timbers to make those objects had been cut — in the year 1021, the team reported in 2022 in Nature.

Vikings weren’t the only ones reaching beyond their horizons at the time. A diverse set of trader-explorers in Afro-Eurasia also survived perilous sea crossings and found each other in towns akin to Ribe. Solar flare–aided radiocarbon dating could bring their stories to light as well.

“We can put different cultures and regions on the same timeline, no matter whether they had a tradition of history writing or not,” Philippsen says. “This makes it much easier to study contacts and the causes and effects of developments in different parts of the world. Environmental and climate records are also dated by radiocarbon … we can also check how societies responded to climate change, and how cultural developments are connected with changes in the environment.”

Archaeologist Mark Horton of the Royal Agricultural University in Cirencester, England, agrees that solar flares “enable us to create a much more precise timetable for history.” But in trading towns around the Indian Ocean where he works, for example, dead trees decay out of existence very quickly, leaving huge gaps in the radiocarbon calibration curve for the Southern Hemisphere, SHCal20, making it more difficult to fill them in as Philippsen did.

Next up for Philippsen is helping Aarhus archaeologist Sarah Croix radiocarbon-date early Christian graves to test King Harald Bluetooth’s claim that he converted Denmark to Christianity. If the graves predate his rule, then Bluetooth would’ve been, let’s say, exaggerating.

“Radiocarbon dating now approaches the precision of traditional historical sources, so it becomes relevant for studying ‘recent’ history, not only prehistory,” Philippsen says. “We can thus study the lives of individuals who are not mentioned in historical sources, i.e., ‘normal people,’ with the same chronological precision as those of the rulers, the literate, or whoever wrote or was written about.”

.image-mobile {

display: none;

}

@media (max-width: 400px) {

.image-mobile {

display: block;

}

.image-desktop {

display: none;

}

}