This post was originally published on this site

When Christopher Mazurek realizes he’s dreaming, it’s always the small stuff that tips him off.

The first time it happened, Mazurek was a freshman at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. In the dream, he found himself in a campus dining hall. It was winter, but Mazurek wasn’t wearing his favorite coat.

“I realized that, OK, if I don’t have the coat, I must be dreaming,” Mazurek says. That epiphany rocked the dream like an earthquake. “Gravity shifted, and I was flung down a hallway that seemed to go on for miles,” he says. “My left arm disappeared, and then I woke up.”

Most people rarely if ever realize that they’re dreaming while it’s happening, what’s known as lucid dreaming. But some enthusiasts have cultivated techniques to become self-aware in their sleep and even wrest some control over their dream selves and settings. Mazurek, 24, says that he’s gotten better at molding his lucid dreams since that first whirlwind experience, sometimes taking them as opportunities to try flying or say hi to deceased family members.

Other lucid dreamers have used their personal virtual realities to plumb their subconscious minds for insights or feast on junk food without real-world consequences. But now, scientists have a new job for lucid dreamers: to explore their dreamscapes and report out in real time.

Dream research has traditionally relied on reports collected after someone wakes up. But people often wake with only spotty, distorted memories of what they dreamed. The dreamers can’t say exactly when events occurred, and they certainly can’t tailor their dreams to specific scientific studies.

“The special thing about lucid dreaming is that you can get even closer to dream content and in a much more controlled and systematic fashion,” says Martin Dresler, a cognitive neuroscientist at the Donders Institute in Nijmegen, Netherlands.

Lucid dreamers who can perform assigned tasks and communicate with researchers during a dream open up tantalizing opportunities to study an otherwise untouchable realm. They are like the astronauts of the dream world, serving as envoys to the mysterious inner spaces created by slumbering minds.

So far, tests in very small groups of lucid dreamers suggest that the strange realities we visit in sleep may be experienced more like the real world than imagined ones. With more emissaries enlisted, researchers hope to probe how sleeping brains construct their elaborate, often bizarre plots and set pieces. Besides satisfying age-old curiosity, this work may point to new ways to treat nightmares. Lucid dream studies could also offer clues about how dreams contribute to creativity, regulating emotions or other cognitive jobs — helping solve the grand mystery of why we dream.

But there are still a lot of problems to solve before lucid dreaming research can really take off. Chief among them is that very few dreamers can become lucid on demand in the lab. Those who can often struggle to do scientists’ bidding or communicate with the waking world. Pinpointing the best techniques to give more people more lucid dreams may assuage those issues. But even if it does, not all scientists agree on what lucid dreams can tell us about the far more common, nonlucid kind.

Are lucid dreams real?

Tales of lucid dreams date back to antiquity. Aristotle may have been the first to mention them in Western literature in his treatise On Dreams. “Often when one is asleep,” he wrote, “there is something in consciousness which declares that what then presents itself is but a dream.”

If Aristotle had lucid dreams often, though, he was probably an outlier. Only about half of people say they’ve ever had a lucid dream, while a mere 1 percent or so say they lucid dream multiple times a week. Modern enthusiasts use various techniques to boost their likelihood of lucid dreaming — such as repeatedly telling themselves before bedtime that they will have a lucid dream, or making a habit of checking whether they’re awake several times a day in the hopes that this routine carries over into their dreams, where a self-check may help them realize they’re asleep. But those practices don’t guarantee lucidity.

The rarity of lucid dreaming may be why modern science took some convincing that it’s even real. For millennia, lucid dreamers’ own testimonies were the only evidence that someone could be self-aware while catching z’s. Some scientists wondered if so-called lucid dreams were just brief waking hallucinations between bouts of sleep.

But within the last few decades, experiments have offered proof that lucid dreams are truly what they seem. It turns out, when someone in a dream purposely sweeps their gaze all the way left, then all the way right, their eyes can match those movements behind closed lids in real life. These motions, measured by electrodes near the eyes, stand out from the smaller optical jitters typical of REM sleep, when most lucid dreams happen. This gives dreamers a crude way to signal they’ve become lucid or send other messages to the outside world (SN: 9/19/81, p. 183). Meanwhile, brain waves and muscle paralysis throughout the rest of the body confirm that the dreamer is indeed asleep.

Neuroscientists are just beginning to realize the potential of that line of communication. Lucid dream research “has been enjoying a renaissance over the last decade,” says neuroscientist Tore Nielsen. He directs the Dream & Nightmare Laboratory at the Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine in Montreal. “This renaissance has made it one of the cutting-edge areas of dream study.”

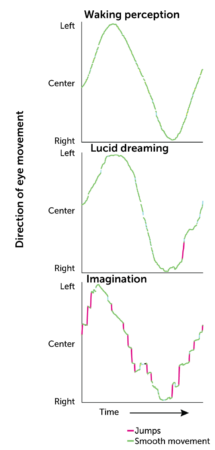

One research team recently deployed experienced lucid dreamers to find out whether dream imagery is more like real-life visuals or imagined ones. While asleep, six lucid dreamers moved their thumbs in either a circle or a line (or both) and traced that motion with their eyes. Participants repeated the same task while awake with their eyes open and in their imaginations with their eyes closed. People’s gazes panned jerkily when they tracked the imagined movements, as though they were viewing something in low resolution. But in dreams, people’s eyes tracked the movements smoothly just as in real life, the team reported in 2018 in Nature Communications.

“It’s been debated really all the way back to the ancient Greeks, are dreams more like imagination, or is it more like perception?” says study coauthor Benjamin Baird, a cognitive psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Texas at Austin. “The smooth tracking data suggests that, at least in that sense, the imagery is more like perception.”

This and other early experiments offer a taste of what dreamstronauts could teach us. But any conclusions based on just a handful of dreamers have to be taken with a grain of salt. “They’re more like proof-of-concept studies,” says Michelle Carr, a cognitive neuroscientist at the Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine. “It needs to be studied in bigger samples.”

That means finding — or creating — more expert lucid dreamers.

Strategies for lucid dreaming

If you want to have a lucid dream, there are a few strategies you can use to up your chances. Besides regularly questioning whether you’re awake and setting an intention before bed to become lucid, you can keep a dream diary. Getting familiar with common characters, events or themes in your dreams may help you recognize when you’re dreaming. Some aspiring lucid dreamers also use a tactic called “wake-back-to-bed.” They wake up extremely early in the morning, stay up for a while, then get more shut-eye. That jolt of alertness right before tumbling back into REM sleep may help them become lucid in a dream.

Such techniques can be hit-or-miss, though. And data on their effectiveness are still pretty murky, Baird says. One study with about 170 Australians, for instance, suggested that checking if you’re awake, setting an intention to become lucid and doing wake-back-to-bed all together can increase your odds of lucid dreaming. But it wasn’t as clear if using just one or two of those practices worked.

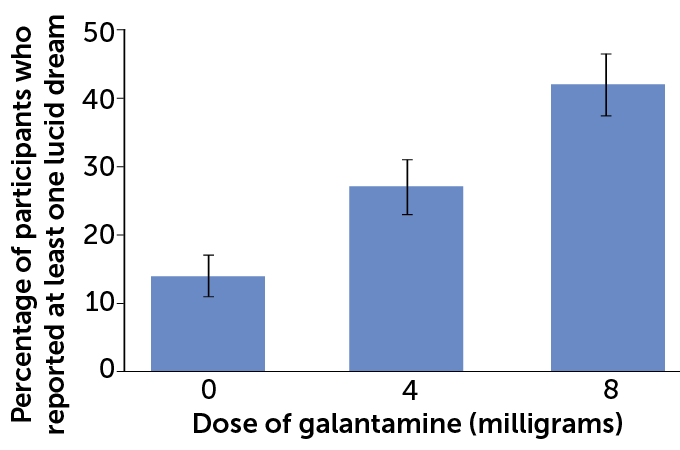

Investigations by Baird and others have shown that the supplement galantamine promotes lucid dreaming, probably by fiddling with neurotransmitters involved in REM sleep. But galantamine can be saddled with side effects such as nausea. And although lucidity itself does not appear to spoil sleep quality, the long-term effects of using galantamine are not well-known. “Personally, I wouldn’t be mucking around with my neurotransmitters every night,” Baird says.

In 2020, Carr and colleagues reported that they’d coaxed 14 of 28 nappers to become lucid in the lab — including three people who’d never before lucid dreamed — no drugs necessary. Before falling asleep, participants learned to associate a cue, such as a series of beeps, with self-awareness. Hearing the same sound again while sleeping reminded them to become lucid. Carr is particularly interested in finding out whether lucid dreaming can help people conquer nightmares, but researchers at Northwestern use the sensory cue strategy to get more lucid emissaries to carry out dream tasks for their experiments.

“Our method is kind of a shortcut,” says Northwestern cognitive neuroscientist Ken Paller. It doesn’t require a lot of mental training or the grueling sleep interruptions that some other lucid dreaming techniques do.

Another shortcut for researchers is to recruit dreamers from a special slice of the population: people with narcolepsy, who are liable to fall asleep suddenly during the day.

“They’re just champions at lucid dreams,” says Isabelle Arnulf, a sleep neurologist who heads the sleep disorders clinic at Pitie-Salpetriere University Hospital in Paris.

In 2018, Arnulf’s team reported a study where 18 of 21 narcolepsy patients signaled lucidity during lab naps. Even with those impressive numbers, a couple of lucid nappers still couldn’t control their dreams well enough to complete their assignment: to do something in a dream that made them briefly stop breathing, such as swimming underwater or speaking. One said after waking that they’d simply forgotten to stop breathing while diving off a cliff, while another said they tried to speak but couldn’t get any words out.

Staying lucid and successfully wrangling dream scenarios present challenges for lucid dreamers — and the scientists relying on them. In one study, lucid dreamers instructed to fill a dream room with objects, such as a clock and a rubber snake, ran into problems; the clock spun wildly, or the snake slithered away. In another experiment, lucid dreamers asked to practice throwing darts were waylaid by only having pencils to throw or being pelted with darts by a nasty doll.

“It’s a lot harder than just passively lucid dreaming in your bed,” says Mazurek, who has participated in several lucid dream studies at Northwestern. “You realize, ‘OK, I have to stabilize the dream. I have to remember what the task is. I have to do the task without the dream falling apart.’ ”

Missions to the moon may be hard, but at least astronauts don’t have to worry about forgetting who or where they are, or their spaceship suddenly turning into a banana.

Despite these challenges, lucid dream expeditions are forging ahead — and fast. In fact, an international crew of dreamfarers, including Mazurek, recently embarked on their most ambitious mission yet.

Real-time dream science

When it comes to getting on-the-ground data, interviewing dreamers in real time is, well, the dream. Instead of just sitting back and watching dreamers do various activities, researchers could ask these agents about their experiences moment to moment, painting the realm of dreams in sharper detail than ever before.

“Reports of dreamed sensations, [such as] tasting certain foods, can be compared with those of actual sensations,” Nielsen says. “Similarly, one could test whether sexual pleasure, certain sounds or other types of experiences are accurately simulated.” These details, he says, might help “probe the limits and mechanisms of dream production.”

Karen Konkoly is especially excited about giving people assignments mid-dream. Say researchers want to know how much dreams help with creative problem-solving. If dreamers are assigned a problem before sleep, they’re liable to mull it over as they nod off. “Even if it feels like the lucid dream, maybe it’s really the time as you’re falling asleep that helped you solve the problem,” says Konkoly, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern. Airdropping a puzzle straight into a dream could better isolate the usefulness of that specific part of sleep.

There’s a whole medley of theories about why people dream, from honing skills to tapping into creativity to processing memories or emotions. “But if you can’t control the dream in real time and then study the outcome, then you never know … if the dream is really doing anything,” Konkoly says. So a few years ago, she, Arnulf, Dresler and others decided to find out if people can receive and respond to outside input while dreaming.

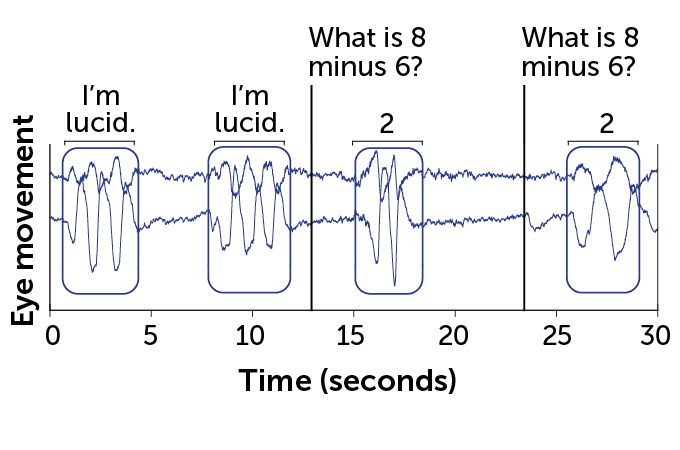

Thirty-six people took snoozes at Northwestern, Arnulf’s lab, Dresler’s lab or another lab that was in Germany. Once sleepers signaled that they were lucid, researchers spoke yes-or-no questions or math problems in the sleepers’ ears. Or, for the Germans, lights flashing different colors conveyed math questions in Morse code. Before conking out, dreamers were told to answer whatever questions they received with eye signals or by smiling and frowning.

“Facial muscles are less inhibited than other muscles during REM sleep,” Arnulf explains. Someone smiling in a dream may not make that expression in real life, but electrodes on the face can register tiny corresponding muscle twitches.

Out of 158 attempts to interrogate lucid dreamers, 29 total correct responses came from six different people. Those six ranged from newbie to frequent lucid dreamers, including Mazurek, who heard scientists’ questions while dreaming he was in a Legend of Zelda game. The rest of the attempts yielded five wrong answers, 28 ambiguous ones and 96 nonresponses.

When Konkoly first saw someone correctly answer a question in their sleep, “my first reaction was to not believe it.” But for 26 of those 29 correct responses, a panel of independent sleep experts unanimously agreed that the dreamers were in the throes of REM sleep when they replied. Nearly 400 attempts to reach sleepers who hadn’t signaled lucidity netted a single correct response — bolstering the researchers’ confidence that correct answers from lucid dreamers weren’t flukes. The results appeared in 2021 in Current Biology.

“I was astonished,” says Robert Stickgold, a cognitive neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School who studies dreams but not lucid ones. “I had no question but that these people are in fact listening and are in fact having lucid dreams at the time of the communication — and that opens up all sorts of possibilities.”

Arnulf and others have since asked lucid dreamers to smile or frown as their dreams became more or less pleasant with the goal of understanding how dreamers experience emotion. Another study, not yet published, tracked when lucid dreamers answered or ignored researchers’ questions to see how people tuned in and out of the real world while dreaming. Knowing which signals break the dream-reality barrier could help “uncover the mechanism of the brain’s disconnection from the external world — which is huge,” Baird says. It could even be relevant for other states of unconsciousness, he adds, such as when someone is put under for surgery.

Limits of lucidity

Even if researchers get all the expert lucid dreamers they need to run all their desired experiments, there’s still one major sticking point to this whole field of study.

“The biggest issue is how far can you push these results to dreaming in general,” Stickgold says. Imagine, for instance, that lucid dreamers get better at a skill by practicing it in their dreams. It’s not clear that people who just happen to have normal dreams about doing those activities, without self-awareness, would reap the same rewards. “It’s a little bit like recruiting major league baseball players to give you some baseline data on how far people can throw balls,” Stickgold says.

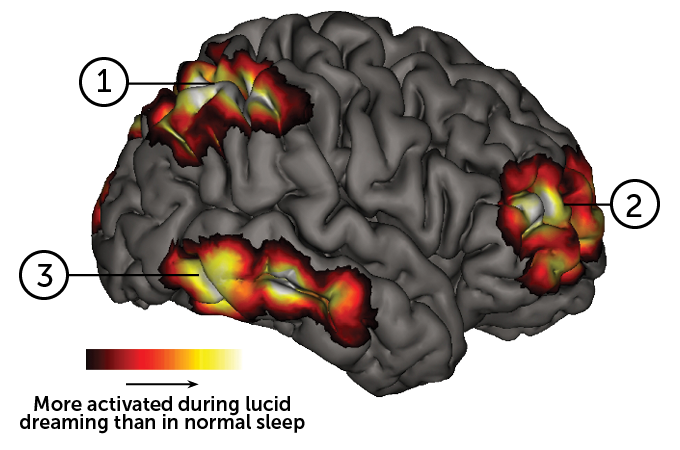

Existing data do suggest that lucid dreamers may have access to parts of the brain that normal dreamers don’t. The lone case study comparing fMRIs of someone’s lucid and nonlucid REM sleep hints that brain areas linked with self-reflection and working memory are more active during lucidity. But those data come from just one person, and it’s not yet clear how such differences in brain activity would affect the outcomes of lucid dream experiments.

Some researchers, including Dresler, resist the idea that lucid dreams are profoundly different from nonlucid ones. “Lucid dreaming is not a strict all-or-nothing phenomenon,” he says, with people often fluttering in and out of awareness. “That suggests that lucid and nonlucid dreaming are in principle something very similar on the neural level and not two completely different animals.”

Perhaps lucidity affects some aspects of the dream experience but not all of them, Baird adds. In terms of how dreams look, he says, “it would be very, very surprising if it was somehow completely different when you become lucid.”

A more thorough inventory of the differences in brain activity between lucid and nonlucid dreams might help settle these questions. But even if lucid dreams don’t represent dreams in general, Nielsen still thinks they’re worth studying. “It is a type of consciousness that has intrigued and amused people for centuries,” he says. “It would be important for science to understand how and why humans have this extraordinary capacity for intentional world simulation.”