This post was originally published on this site

We’ve now seen farther, deeper and more clearly into space than ever before.

The first image from the James Webb Space Telescope, released in a White House briefing on July 11, shows thousands of distant galaxies. The galaxies captured here lie behind a cluster of galaxies about 4.6 billion light-years away. The mass from those galaxies distorts spacetime in such a way that objects behind the cluster are magnified, giving astronomers a way to peer about 13 billion years into the early universe.

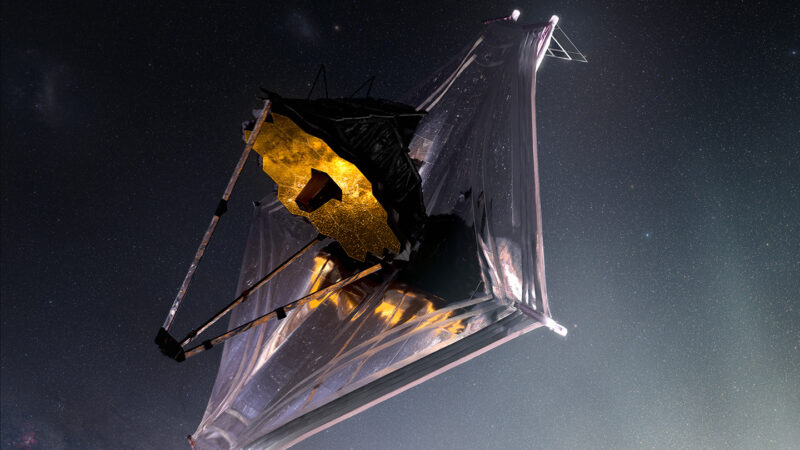

Even with that celestial assist, other existing telescopes could never see so far. But the James Webb Space Telescope, also known as JWST, is incredibly large — at 6.5 meters across, its mirror is nearly three times wider than that of the Hubble Space Telescope. It also sees in the infrared wavelengths of light where distant galaxies appear. Those features give it an edge over previous observatories.

“The James Webb Space Telescope allows us to see deeper into space than ever before, and in stunning clarity,” said Vice President Kamala Harris in the July 11 briefing. “It will enhance what we know about the origins of our universe, our solar system, and possibly life itself.”

Although this first image represents the deepest view of the cosmos to date, “this is not a record that will stand for very long,” astronomer Klaus Pontoppidan of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore said in a June 29 news briefing. “Scientists will very quickly beat that record and go even deeper.”

And this image is just the first. On July 12, astronomers plan to release first images of a stellar birthplace, a nebula surrounding a dying star, and a group of closely interacting galaxies, plus the first spectrum of an exoplanet’s light, a clue to its composition. All these images are a glimpse of what JWST will continue to reveal over its decade-plus planned mission.

This first image has been a very long time coming. The telescope that would become JWST was first dreamed up in the 1980s, and the planning and construction suffered years of budget issues and delays (SN: 10/6/21).

The telescope finally launched on December 25. It then had to unfold and assemble itself in space, travel to a gravitationally stable spot about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, align its insectlike primary mirror made of 18 hexagonal segments and calibrate its science instruments (SN: 1/24/22). There were hundreds of possible points of failure in that process, but the telescope unfurled successfully and got to work.

In the months following, the telescope team released teasers of imagery from calibration, which already showed hundreds of distant, never-before-seen galaxies. But the images now being released are the first full-color pictures made from the data scientists will use to start unraveling mysteries of the universe.

For the telescope team, the relief in finally seeing the first images was palpable. “It was like, ‘Oh my god, we made it!’” says image processor Alyssa Pagan, also of Space Telescope Science Institute. “It seems impossible. It’s like the impossible happened.”

In light of the expected anticipation surrounding the first batch of images, the imaging team was sworn to secrecy. “I couldn’t even share it with my wife,” says Pontoppidan, leader of the team that produced the first color science images.

“You’re looking at the deepest image of the universe yet, and you’re the only one who’s seen that,” he says. “It’s profoundly lonely.” Soon, though, the team of scientists, image processors and science writers was seeing something new every day for weeks as the telescope downloaded the first images. “It’s a crazy experience,” Pontoppidan says. “Once in a lifetime.”

For Pagan, the timing is perfect. “It’s a very unifying thing,” she says. “The world is so polarized right now. I think it could use something that’s a little bit more universal and connecting. It’s a good perspective, to be reminded that we’re part of something so much greater and beautiful.”

This story will be updated as more images are released.