This post was originally published on this site

Three virologists have won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for the discovery of the hepatitis C virus.

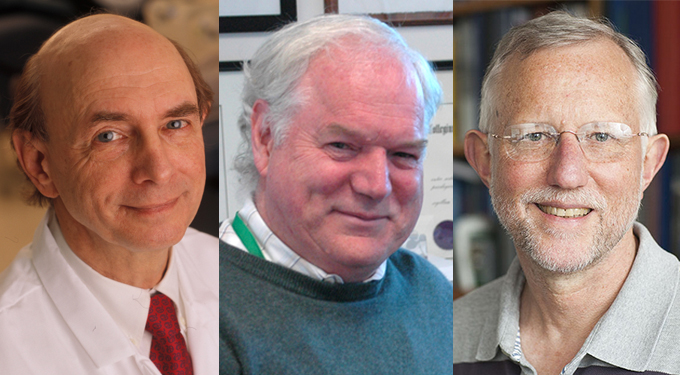

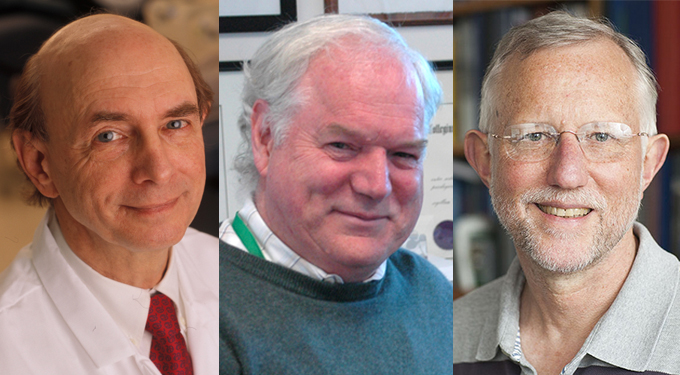

Harvey Alter, of the U.S. National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., Michael Houghton, who is now at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, and Charles Rice now of The Rockefeller University in New York City will split the prize of 10 million Swedish kronor, or more than $1.1 million, the Nobel Assembly of the Karolinska Institute announced October 5.

About 71 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C infections. An estimated 400,000 people die each year of complications from the disease, which include cirrhosis and liver cancer. Today, the major way people get infected is through contaminated needles used for injecting intravenous drugs, but when the researchers made their discoveries in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, blood transfusions were an important source of hepatitis C infection.

“This is a bit overdue,” says Dennis Brown, chief science officer of the American Physiological Society. It often takes decades before scientific achievements are recognized by the Nobel committee. One reason for the recognition this year may be COVID-19, Brown says. “This keeps virology and viruses in the public eye,” he says. “It might be a push to put science at the forefront, to say when we put money into this and when we have well-funded people working on these viruses, we can actually do something about them.”

Alter worked at a large blood bank at NIH in the 1960s when hepatitis B was discovered. (That discovery won the 1976 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine (SN: 10/23/76).) Blood could be screened so that people wouldn’t get that virus from a transfusion, but patients were still developing hepatitis. Alter and colleagues showed in the mid- and late 1970s that a new virus, dubbed “non-A, non-B” was causing the infection, and that the virus could be used to transmit the disease to chimpanzees (SN: 4/1/78).

Just over a decade later, Houghton, working at the pharmaceutical company Chiron Corp. (now part of Novartis), developed a way to pull fragments of the virus’s genetic material from the blood of infected chimpanzees and developed a test to screen out hepatitis C-infected blood (SN: 5/14/88) . It took so long to isolate the virus’s genetic material because Houghton “had to wait until the technology was available,” Brown says.

The blood test Houghton and colleagues developed was used to screen blood all around the world and dramatically decreased hepatitis C infections, said Gunilla Karlsson Hedestam, an immunologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm who described the laureates’ contributions. Before then, “it was a bit like Russian roulette to get a blood transfusion” said Nils-Göran Larsson, a member of the selection committee.

But a question still remained about whether the hepatitis C virus alone was responsible for the infection. Rice and colleagues working at Washington University in St. Louis stitched together genetic fragments of the virus pulled from the blood of infected chimpanzees into a working virus and demonstrated that it could cause hepatitis in animals. “This provided conclusive evidence that the cloned hepatitis C alone could cause the disease,” Karlsson Hedestam said.

Thomas Perlmann, secretary general of the Nobel Assembly, had to try several times before he reached Alter and Rice to give them news of their win. Alter said he got up angrily the third time his phone rang before 5 a.m. EDT, but his anger soon turned to shock. “It’s otherworldly. It’s something you don’t think will ever happen, and sometimes don’t think you deserve to happen. And then it happens,” he said in an interview posted at nobelprize.org. “In this crazy COVID year, where everything is upside down, this is a nice upside down for me.”