This post was originally published on this site

Krystal Tsosie grew up playing in the wide expanse of the Navajo Nation, scrambling up sandstone rocks and hiking in canyons in Northern Arizona. But after her father started working as a power plant operator at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center, the family moved to the city. “That upbringing in a lower socioeconomic household in West Phoenix really made me think about what it meant to be a good advocate for my people and my community,” says Tsosie, who like other Navajo people refers to herself as Diné. Today, she’s a geneticist-bioethicist at Arizona State University in Tempe. The challenges of urban life for Tsosie’s family and others, plus the distance from the Navajo Nation, helped spark the deep sense of community responsibility that has become the foundation of her work.

Tsosie was interested in science from an early age, volunteering at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center in high school with the hopes of eventually becoming a doctor. She remembers seeing posters at the Indian Health Service clinic in Phoenix warning against the dangers of rodents and dust. The posters were put up in response to cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, or HPS, in the Four Corners area. Though the disease had not been identified by Western science until that 1993 outbreak, it had long been known within the Navajo tradition. Learning how Navajo oral traditions helped researchers understand HPS made Tsosie want to work in a laboratory studying diseases, instead of becoming a practicing physician.

Tsosie settled on cancer biology and research after college, in part because of the health and environmental impacts of decades of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. But after leaving Arizona for the first time after college, Tsosie was confronted with the profit-driven realities and what she calls the “entrenched, systemic racism” of the biomedical space. She saw a lack of Indigenous representation and disparities that prevented Indigenous communities from accessing the best health care. Tsosie began asking herself whether her projects would be affordable and accessible to her community back home. “I didn’t like the answer,” she says.

The need for Indigenous geneticists

So Tsosie returned to Arizona State to work on a master’s degree in bioethics with the intention of going to law school. But the more she learned about how much genetic research relies on big data and how those data are shared and used, the more Tsosie realized there was a huge need for Indigenous geneticists.

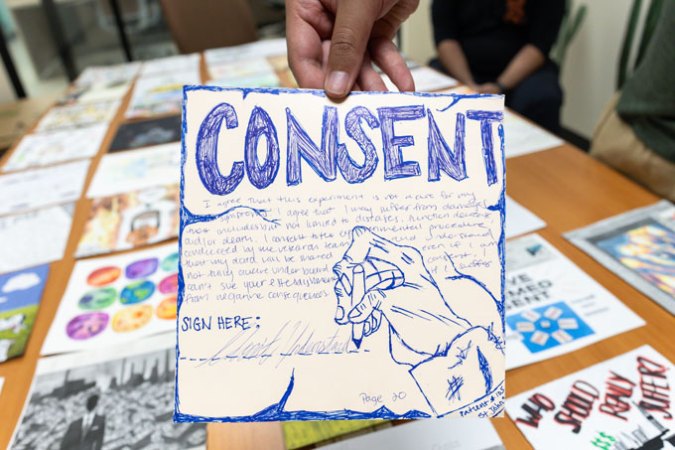

Around the world, scientific use of Indigenous genetic data has led to repeated violations of rights and sovereignty. For example, beginning in 1990, Havasupai Tribal members gave DNA samples to researchers from ASU, hoping to understand more about diabetes in their community. Researchers eventually used the Havasupai DNA in a range of studies, including for research on schizophrenia and alcoholism, which the Havasupai say they had not been properly informed about or consented to. In 2010, the Arizona Board of Regents settled with Tribal members for $700,000 and the return of the DNA samples, among other reparations.

The Havasupai case is perhaps the most high-profile example in a long history of Western science exploiting Indigenous DNA. “We have an unfortunate colonial, extractive way of coming into communities and taking samples, taking DNA, taking data, and just not engaging in equitable research partnerships,” Tsosie says.

This history prompted the Navajo Nation in 2002 to place a “moratorium on genetic research studies conducted within the jurisdiction of the Navajo Nation.” It has also, along with the growth of genomics, convinced Tsosie that Indigenous geneticists must play a big role in protecting Indigenous data and empowering Indigenous peoples to manage, study and benefit from their own data. “It’s the right of indigenous peoples to exercise authority, agency, autonomy, and self-direct and self-govern decisions about our own data,” she says.

Tsosie was determined to become one of those Indigenous geneticists, and in 2016, she began dissertation research at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Around that time, she met Keolu Fox and Joseph Yracheta, two other Indigenous scientists interested in genetics. Fox, who is Kānaka Maoli and a geneticist at the University of California, San Diego, believes Tsosie and others prioritizing Indigenous health and rights represent a paradigm shift in the field of genetics. “Minority health is not an afterthought to someone like Krystal, it is the primary goal,” Fox says. “We have not been allowed to operate large laboratories in major influential academic institutions until now. And that’s why it’s different.”

In 2018, Tsosie, Yracheta and colleagues, with key support from Fox, founded the Native BioData Consortium, an Indigenous-led nonprofit research institute that brings Indigenous scholars, experts and scientists together. The consortium’s biorepository, which Tsosie believes is the first repository of Indigenous genomic data in North America, is located on the sovereign land of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota. The consortium supports various research, data and digital capacity building projects for Indigenous peoples and communities. These projects include researching soil health and the microbiome and creating a Tribal public health surveillance program for COVID that has Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certification, as well as hosting workshops for Indigenous researchers.

The work may be even more essential given current genomics trends: With Indigenous nations in the United States restricting access to their DNA, researchers and corporations seek DNA from Indigenous peoples in Latin America.

“We are now in the second era of discovery or the second era of colonization,” says Yracheta, who is P’urhépecha from Mexico, director of the consortium and a doctor of public health candidate in environmental health at Johns Hopkins University. “Lots of Indigenous spaces are small and shrinking and we’re trying to prevent that happening by asserting Indigenous data sovereignty not only over humans and biomedical data, but all data.”

Tsosie, Yracheta says, consistently works to bring Indigenous values and accountability to the consortium’s work and has an invaluable combination of skills. “She has a lot of really hard-core scientific background and now she’s mixing it with bioethics, law and policy and machine learning and artificial intelligence,” he says. “We make a really good team.”

Training the next generation

Today, Tsosie leads the Tsosie Lab for Indigenous Genomic Data Equity and Justice at ASU. One lab project involves working with Tribal partners in the Phoenix area to create a multiethnic cohort for genomic and nongenomic data. The data, which will include social, structural, cultural and traditional factors, could provide a more complex picture of health disparities and what causes them, as well as a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous identity and health.

In addition to her own research, Tsosie spends time teaching, mentoring, traveling to speak about the importance of data sovereignty, and serving as a consultant for tribes who want to develop their own data policies. “We’re not just talking about doing research with communities,” she says. “We’re also helping to cocreate legal policies and resolutions and laws to help Tribal nations and Indigenous peoples protect their data and rights to their data.”

At ASU, Tsosie says, she is in the position to push back against some of the prevailing trends in Indigenous genomics, including the tendency to lump Indigenous people together, regardless of environmental, cultural and political factors. “This is an opportunity for my lab to really explore the fact that being Indigenous is not always a biological category. It’s one that’s mediated by culture, and also sociopolitical factors that have sometimes been imposed on us,” Tsosie says.

And while Tsosie’s goals are ambitious, she is equally committed to uplifting the next generation of Indigenous scientists. “Krystal puts in so much time and energy into ensuring that the next generation of students are getting ecosystems where they feel safe and protected to learn about new disciplines,” Fox says. “It’s just so special.”

To Tsosie, empowering Indigenous communities to make decisions about their data and supporting Indigenous students are part of the same mission. “It just makes me happy to think about several academic generations in the future, how many of us will be occupying this colonial space that we call academia,” she says. “Then we can really start shifting this power imbalance towards something that is truly enriching and powerful for our peoples and our communities.”