A press conference on this topic will be held Tuesday, Aug. 17, at 9 a.m. Eastern time online at www.acs.org/fall2020pressconferences.

Category: Uncategorized

Patients taking long-term opioids produce antibodies against the drugs

University of Wisconsin-Madison scientists have discovered that a majority of back-pain patients they tested who were taking opioid painkillers produced anti-opioid antibodies. These antibodies may contribute to some of the negative side effects of long-term opioid use.

Hurricanes have names. Some climate experts say heat waves should, too

Hurricane Maria and Heat Wave Henrietta?

For decades, meteorologists have named hurricanes and ranked them according to severity. Naming and categorizing heat waves too could increase public awareness of the extreme weather events and their dangers, contends a newly formed group that includes public health and climate experts. Developing such a system is one of the first priorities of the international coalition, called the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance.

Hurricanes get attention because they cause obvious physical damage, says Jennifer Marlon, a climate scientist at Yale University who is not involved in the alliance. Heat waves, however, have less visible effects, since the primary damage is to human health.

Heat waves kill more people in the United States than any other weather-related disaster (SN: 4/3/18). Data from the National Weather Service show that from 1986 to 2019, there were 4,257 deaths as a result of heat. By comparison, there were fewer deaths by floods (2,907), tornadoes (2,203) or hurricanes (1,405) over the same period.

What’s more, climate change is amplifying the dangers of heat waves by increasing the likelihood of high temperature events worldwide. Heat waves linked to climate change include the powerful event that scorched Europe during June 2019 (SN: 7/2/19) and sweltering heat in Siberia during the first half of 2020 (SN: 7/15/20).

Some populations are particularly vulnerable to health problems as a result of high heat, including people over 65 and those with chronic medical conditions, such as neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes. Historical racial discrimination also places minority communities at disproportionately higher risk, says Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital and a member of the new alliance. Due to housing policies, communities of color are more likely to live in urban areas, heat islands which lack the green spaces that help cool down neighborhoods (SN: 3/27/09).

Part of the naming and ranking process will involve defining exactly what a heat wave is. No single definition currently exists. The National Weather Service issues an excessive heat warning when the maximum heat index — which reflects how hot it feels by taking humidity into account — is forecasted to exceed about 41° Celsius (105° Fahrenheit) for at least two days and nighttime air temperatures stay above roughly 24° C (75° F). The World Meteorological Organization and World Health Organization more broadly describe heat waves as periods of excessively hot weather that cause health problems.

Without a universally accepted definition of a heat wave, “we don’t have a common understanding of the threat we face,” Bernstein says. He has been studying the health effects of global environmental changes for nearly 20 years and is interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Defined categories for heat waves could help local officials better prepare to address potential health problems in the face of rising temperatures. And naming and categorizing heat waves could increase public awareness of the health risks posed by these silent killers.

“Naming [heat waves] will make something invisible more visible,” says climate communicator Susan Joy Hassol of Climate Communication, a project of the Aspen Global Change Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Colorado that’s not part of the new alliance. “It also makes it more real and concrete, rather than abstract.”

The alliance is in ongoing conversations with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the World Meteorological Organization and other institutions to develop a standard naming and ranking practice.

“People know when a hurricane’s coming,” Hassol says. “It’s been named and it’s been categorized, and they’re taking steps to prepare. And that’s what we need people to do with heat waves.”

Why do we miss the rituals put on hold by the COVID-19 pandemic?

For over a thousand years, the various prayers of the Catholic Holy Mass remained largely unaltered. Starting in the 1960s, though, the Catholic Church began implementing changes to make the Mass more modern. One such change occurred on November 27, 2011, when the church attempted to unify the world’s English-speaking Catholics by having them all use the same wording. The changes were slight; for instance, instead of responding to the priest’s “The Lord be with you” with “And also with you,” the response became: “And with your spirit.”

The seemingly small modification sparked an uproar so fierce that some leaders warned of a “ritual whiplash.”

The new wording has stayed intact, but that outsize reaction did not surprise ritual scholars. “The ritual reflects the sacred values of the group,” says Juliana Schroeder, a social psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Those [ritual actions] are nonnegotiable.”

But in the midst of the global coronavirus pandemic, people are being forced to renegotiate rituals large and small. Cruelly, a pandemic that has taken more than half a million lives worldwide has disrupted cherished funeral and grieving rituals.

Even when rituals can be tweaked to fit the moment, such as virtual religious services or car parades in place of graduation ceremonies, the experiences don’t carry the same emotional heft as the real thing. That’s because the immutability of rituals — their fixed and often repetitive nature — is core to their definition, Schroeder and others say. So too is the symbolic meaning people attach to behaviors; doing the ritual “right” can matter more than the outcome.

Why do such behaviors even exist? Anthropologists, psychologists and neuroscientists have all weighed in, so much so that the theories used to explain the purpose of rituals feel as myriad as the forms rituals have taken the world over.

That growing body of research can help explain the unrest people are now experiencing as beloved rituals go virtual or get punted to some unsettled future. Multiple lines of evidence suggest, for instance, that rituals help with emotional regulation, particularly during periods of uncertainty, when control over events is not within reach. Rituals also foster social cohesion. Engaging in rituals, in other words, could really help people and societies navigate this new and fraught global landscape.

“This is exactly the time … when we want to be able to congregate with other people, get social support and engage in the kinds of collective rituals that promote cooperation [and] reduce anxiety,” says developmental psychologist Cristine Legare of the University of Texas at Austin. And yet, with COVID-19, congregating in any sort of group can be downright dangerous. What does that mean for how we persevere?

An illusion of control

Polish-born British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski documented rituals and speculated on their reason for being in the early 1900s. Living among fishermen on the Trobriand Islands off New Guinea from 1915 to 1918, Malinowski noticed that when the fishermen stuck to the safe and reliable lagoon, they described their successes and failures in terms of skill and knowledge.

But when venturing into deeper waters, the fishermen practiced rituals during all stages of the journey, acts Malinowski collectively referred to as “magic.” Before setting out, the men consumed special herbs and sacrificed pigs. While on the water, the fishermen beat the canoe with banana leaves, applied body paint, blew on conch shells and chanted in synchrony. Malinowski later used that Trobriand data to comment more broadly on human behavior.

“We find magic wherever the elements of chance and accident, and the emotional play between hope and fear, have a wide and extensive range. We do not find magic whenever the pursuit is certain, reliable and well under control of rational methods,” Malinowski wrote in an essay published posthumously in 1948.

Working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, American anthropologist Roy Rappaport built on that idea by developing a social framework for ritual, theorizing that such behaviors help individuals and groups maintain a balanced psychological state — much like a thermostat system that controls when the heat kicks on. In recent decades, anthropologists and psychologists have tested the idea that rituals regulate emotions.

In 2002, during a period of intense fighting between Palestine and Israel, anthropologist Richard Sosis took a taxi from Jerusalem to Tzfat, in northern Israel. Sosis, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, noticed that the driver was carrying the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms despite professing little religious inclination and admitting he didn’t read it. The driver said the book was there for his protection. Sosis suspected that the mere presence of the book helped the cabdriver manage the stress of possibly violent encounters. But how?

A few years later, Sosis and his team recruited 115 Orthodox Jewish women from Tzfat to take part in a study about psalm reading. By the time interviews began in August 2006, war between Israel and Lebanon’s Hezbollah had broken out; 71 percent of the women in the study had fled Tzfat for central Israel.

The researchers asked the women to list their three top stressors during the war. The women listed many of the same issues, with a few important differences. Almost 76 percent of those who stayed in Tzfat reported concerns about property damage compared with just 11 percent of women who left. Women who left were more likely than women who stayed to worry about stressors associated with displacement, such as inadequate child care (32 percent versus 9 percent) and a lack of schedule (32 percent compared with 6 percent).

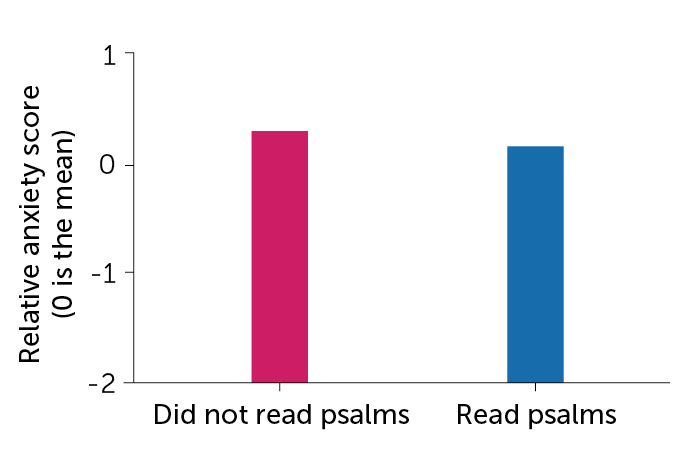

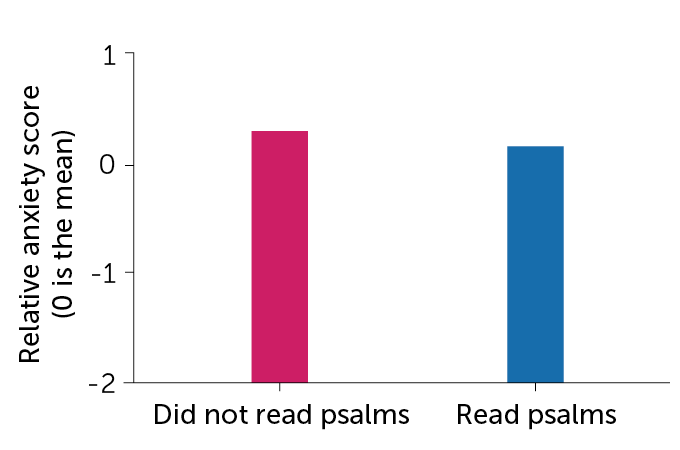

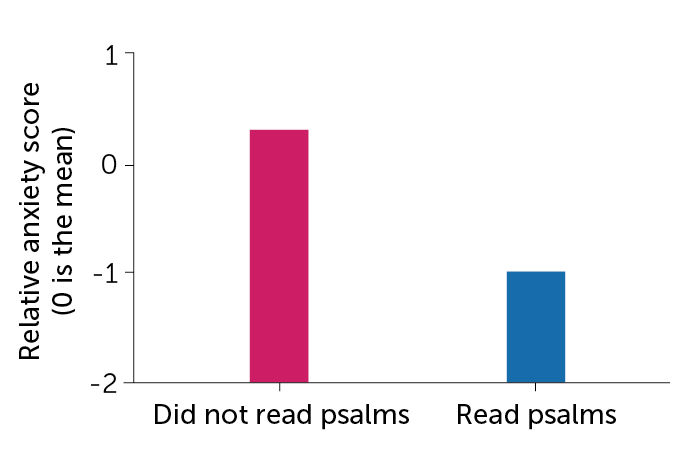

The researchers also had the women fill out a questionnaire about anxiety. Psalm reading provided anxiety relief, but the psalms’ true power depended on the women’s location. That is, the anxiety scores of women who left Tzfat and recited psalms were only slightly lower than the scores of women who left but did not recite psalms. The anxiety scores of women who stayed in Tzfat and recited psalms, on the other hand, were more than 50 percent lower than women who stayed and did not recite psalms. Overall, those who remained in Tzfat and recited psalms had lower anxiety scores than those who left.

“Reciting the psalms was effective under conditions in which the stressor was uncontrollable. But once you could devise instrumental solutions to a problem, such as taking care of your kids or finding work, reciting psalms isn’t going to fix anything,” says Sosis, whose findings appeared in American Anthropologist in 2011. Several more recent studies conducted on individuals living in war and earthquake zones mirror Sosis’ finding that rituals give participants a sense — or a comforting illusion — of control over the uncontrollable.

Testing the illusion

In recent years, researchers have begun testing the psychological benefits of rituals using controlled experiments and physiological monitors. In one study, Dimitris Xygalatas, an anthropologist and psychologist also at the University of Connecticut, and colleagues recruited 74 Hindu women in southwest Mauritius. Thirty-two women were sent to a lab and the rest to the local temple. All participants completed a survey evaluating their overall anxiety and were fitted with heart rate monitors.

Researchers elicited anxiety among the women by giving them three minutes to put together a speech on their flood preparedness — natural disasters are a common threat to the island — to ostensibly be evaluated later by government experts.

Afterward, women at the temple performed their usual routine — praying to Hindu deities and offering fruits and flowers. These actions tended to follow the same pattern across participants, such as holding an oil lamp or incense stick and moving it slowly clockwise before the statue of a deity. Women at the lab, meanwhile, sat quietly for 11 minutes, about the same time it took for the other women to pray. All participants then took a second anxiety survey.

On the first survey, both groups reported similar levels of anxiety. But the women who then performed their rituals at the temple reported half as much anxiety as the women in the lab.

That divergence also showed up on the heart monitors, specifically on a marker for resilience known as heart rate variability. During periods of stress, heart rate becomes less variable and the time between beats gets shorter.

Spacing between heartbeats for women who sat quietly increased only about 3 percent from the baseline rate, measured when the women first arrived at the lab. But for women who performed the ritual and experienced stress reduction, the space between beats lengthened 22 percent from the baseline rate, Xygalatas and colleagues reported in the Aug. 17 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. That is, heart rate variability was 30 percent higher among women performing the ritual than women who sat quietly.

Xygalatas’ and Sosis’ studies suggest that engaging in the individual, repetitive rituals often seen in religious practices, such as reading psalms or reciting prayers, could serve as a balm during the pandemic. But, typically, even individual rituals carry a social component. For instance, it was common for women in Sosis’ study to divvy up the 150 passages so that they could read the entire Book of Psalms in a single day. “Women recognize that other women are also engaging in these psalm-recitation activities,” Sosis says.

Researchers largely concur that the power of rituals rests within a larger social fabric. Rituals “are created by groups, and individuals inherit them,” Legare says. The problem is, during the pandemic, even if people are engaging in rituals on their own, those larger groups are now fractured.

Merging with the in-group

The idea that rituals serve to bond individuals is not new. Fourteenth century scholar Ibn Khaldūn used the term asabiyah, Arabic for solidarity, to describe the social cohesion that emerges from engaging in collective rituals. Khaldūn believed that solidarity had its foundations in kinship but extended to tribes and even nations. Centuries later, in the early 1900s, French sociologist Émile Durkheim theorized that group rituals fostered unity among practitioners.

In contemporary times, researchers have sought to understand the ways in which rituals bind people together. Work by University of Oxford anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse suggests that rituals exist on either side of a dichotomy. On one side are “imagistic” rituals that fuse people together, often more tightly than kin, through intense moments and painful rites of passage, such as piercing or tattooing one’s body and walking on fire.

Today, imagistic rituals are much less common than the “doctrinal” rituals that characterize modern-day life — prayers, religious services and various regimented rites of passage, such as baby showers and birthday parties. Such rituals appear to have become established as societies grew increasingly complex with the emergence of agriculture. While not binding people as tightly as imagistic rituals, doctrinal rituals enable group members to both identify those in their larger group and spot and police social deviants, Whitehouse says.

Several studies of contemporary communities support the idea that doctrinal rituals help unite social groups. In the early 2000s, Sosis compared cooperation among members of secular versus religious collective farming settlements, called kibbutzim, in Israel. The two types of kibbutzim operated in similar ways, except that men in the religious settlements were required to pray in groups of 10 or more people at least three times a day. Women also prayed, but did not have to do so collectively. Sosis reported in Current Anthropology in 2003 that members of religious kibbutzim were more cooperative, as evidenced by taking less money out of a communal pot, than members of secular kibbutzim. That difference was driven entirely by those ritual-practicing men in the religious kibbutzim.

In her research, Legare — who invents rituals to see how children understand such practices — has shown that children use rituals to identify and reinforce connections with members of their own group while shunning those outside the group. Recently, Legare, working with Nicole Wen, now at Brunel University London, divided 60 children, ages 4 to 11, into two groups. The children were given wristbands denoting their group’s color. One group was then walked through a highly scripted, ritualized process to make a bead necklace with prompts like: “First, hold up a green string. Then, touch a green star to your head. Then, string on a green star” and so on. The other group made necklaces with the same materials, but no script.

The activities continued for two weeks, during which the researchers measured how long children spent comparing their handiwork to that of members of their own group and how long they spent watching members of the other group, such as by looking over their shoulders. Reporting in the Aug. 17 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, the team found that during the experiment, children in the ritual group spent on average twice as much time as children in the nonritual group showing off their necklaces to members of their own group and monitoring the behavior of those not in the group.

Working in a group helps people bond even without a script to follow, Legare says. But “rituals take the effects of a group experience and turn them way up.”

Legare’s project and others also illustrate how rituals engender in-groups and out-groups. Whitehouse’s work suggests that shared traumatic experiences, which may include imagistic rituals, contribute to the cohesion of terrorist cell networks, where fighters would sooner die for fellow fighters than even family (SN: 7/9/16, p. 18).

The pandemic itself is the latest example of how a shared traumatic experience and the resulting rituals — Zoom parties, alliances around wearing or eschewing masks and reactions to civil rights rallies — can break or bind communities.

“Human social groups … [are] always going to be vulnerable to in-group preferences and out-group biases,” Legare says. Whether we use ritual for good — or evil — is up to us.

Pandemic asynchrony

Certain rituals, such as singing and dancing together, are particularly good at amplifying group cohesion and a spirit of generosity. But these group rituals, tragically, also can spread the coronavirus.

On March 10 in Skagit County, Wash., 61 members of a church choir met for practice. One singer, who had been feeling unwell for a few days, later tested positive for COVID-19. Within weeks, almost 90 percent of those in attendance had developed similar symptoms, with 33 confirmed cases; two members died from the disease. Similar stories linking choir practice to superspreading events have emerged. And the collective singing that characterizes so many religious services has emerged as a particularly risky activity in this pandemic.

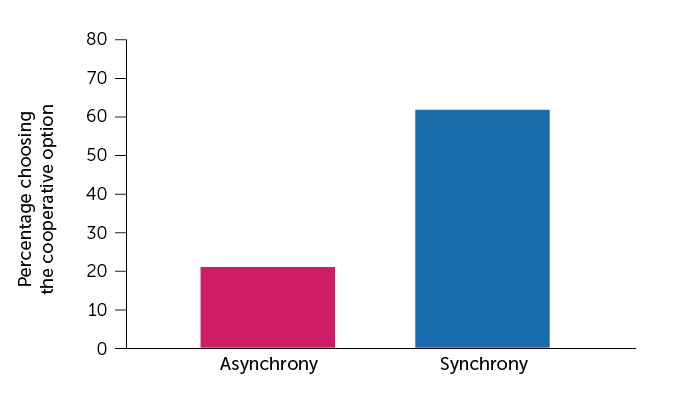

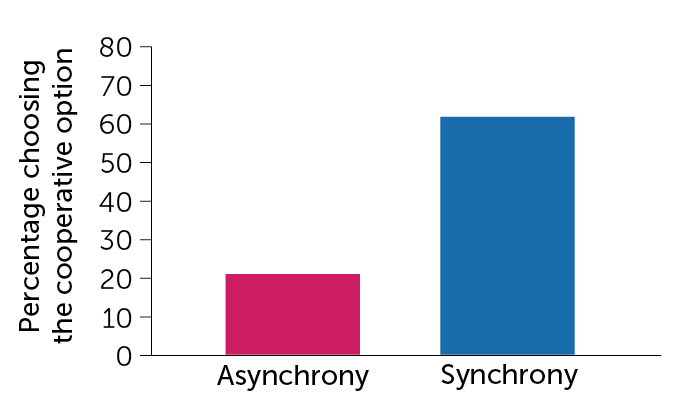

In a series of experiments reported in 2013, researchers tested to see if dancing or chanting together made people feel more generous toward members of their group. One of the tests divided 27 volunteers into groups of three and handed them a list of one-syllable words divided into three columns. The researchers told some of the groups to go down the list and chant the words together for six minutes, keeping in beat with a metronome — effectively a ritual performed in synchrony. Other groups recited the words sequentially, with each member reading the words in only one column.

The participants then played a cooperative game within their groups. Anonymously, each member could choose either option X, a guaranteed prize of $7, or option Y, a prize of $10 that came through only if every group member chose Y. If a single member chose X, no one would get money. Reporting in PLOS ONE, the researchers found that 62 percent of participants who chanted together chose Y compared with just 21 percent who chanted in sequence.

Other synchronized activities, such as marching, dancing, rowing and even collective social distancing while out in public, can bond participants, Whitehouse says. The alliance forged by synchrony is arguably playing out across the United States even now as both Black and non-Black people march and chant in unison to protest police brutality and systemic racism. In any context, Legare says, synchrony “is a powerful social catalyst.”

New rituals

Ironically, as the pandemic makes practicing rituals, particularly social rituals, profoundly challenging, decades of research have made clear that people turn to such regimented behaviors during periods of unrest. “Anthropologists have long observed that during times of anxiety, you see spikes in ritual activity,” Xygalatas says.

So even as rituals are being disrupted and diluted, people are seeking new sources of solace. Many people, for instance, are turning to their immediate family members to fill that ritual void.

“It’s possible that lockdowns are actually leading to the invention of new family rituals that foster this kind of resilience, ranging from the arrangement of rainbows and teddy bears in windows to the revival of more traditional family rituals like eating, singing [and] telling stories together,” Whitehouse says.

People are also finding new ways to experience old traditions. Rachel Fraumann, a Methodist minister in Barre, Vt., says online attendance at her recorded sermons has more than doubled since mid-March. In her view, now is a great time for the ritually and spiritually adrift to shop around for their ritual fit.

Such “shopping” doesn’t need to occur within a religious context. Secular rituals, such as those centered around crafts, music or sports, have shown similar promises, and pitfalls, as religious activities, says Oxford cognitive anthropologist Martha Newson. Which means now could be a great time to try new hobbies with a solo component as a way to practice in the here and now, with a group component to look forward to after the pandemic ends, such as knitting with the goal of joining a knitting circle or buying a rowing machine to get fit enough to join the local crew team, where bodies move in sync.

Creating rituals outside of religion, though, can be hard to get right. “It’s not the hobby, it’s the people who do the hobby who make the tribe. Precisely what the magic ingredients are for that, we [don’t] know,” Newson says.

Those challenges won’t stop people from trying once the pandemic ends, Legare says. “I would predict that there will be an increase in attending religious services but [also] an increase in attending all kinds of social group activities. People are so starved for social interaction, I would predict increased enrollment in absolutely everything.”

Newly discovered cells in mice can sense four of the five tastes

Taste buds can turn food from mere fuel into a memorable meal. Now researchers have discovered a set of supersensing cells in the taste buds of mice that can detect four of the five flavors that the buds recognize. Bitter, sweet, sour and umami — these cells can catch them all.

That’s a surprise because it’s commonly thought that taste cells are very specific, detecting just one or two flavors. Some known taste cells respond to only one compound, for instance, detecting sweet sucralose or bitter caffeine. But the new results suggest that a far more complicated process is at work.

When neurophysiologist Debarghya Dutta Banik and colleagues turned off the sensing abilities of more specific taste cells in mice, the researchers were startled to find other cells responding to flavors. Pulling those cells out of the rodents’ taste buds and giving them a taste of several compounds revealed a group of cells that can sense multiple chemicals across different taste classes, the team reports August 13 in PLOS Genetics.

“We never expected that any population of [taste] cells would respond to so many different compounds,” says Dutta Banik, of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

But taste cells don’t respond to flavors in insolation; the brain and the tongue work together as tastemakers (SN: 11/24/15). So the scientists monitored the brain to see if it received bitter, sweet or umami signals when mice lacked a key protein needed for these broadly tasting cells to relay information. Those observations revealed that without the protein, the brain didn’t get the flavor messages, which was also shown when mice slurped bitter solutions as though they were water even though the rodents hate bitter tastes, says Dutta Banik, who did the work at the University at Buffalo in New York.

While these broadly sensing cells were incommunicado, the also brain seemed to miss signals from other more specific taste cells, such as those for sensing bitterness. So it may be that the broadly sensing cells work with the others to communicate taste information.

“The presence of these [newly discovered] cells completely disrupts how people think the taste bud works,” says Kathryn Medler, a neurophysiologist at the University at Buffalo in New York.

Life without functioning taste cells would be beyond bland. Taste is crucial for survival, Medler says. When taste diminishes, with age or after treatments such as chemotherapy, people can lose their appetites and become malnourished. A working sense of taste also helps protect us from eating something spoiled or toxic.

Since taste works similarly in mice and humans, Medler says, untangling how such cells work may someday help scientists bring the flavor back for people who have lost the sense of taste.

“The long-term implications are pretty profound,” says Stephen Roper, a neurobiologist at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla., who was not involved with the work. Learning how these cells sense and how information passes between them, the buds and the brain, he says, could someday allow people to engineer taste signals.

Patients’ Access to Opioid Treatment Cumbersome

The “secret shopper” study used trained actors attempting to get into treatment with an addiction provider in 10 U.S. states. The results, with more than 10,000 unique patients, revealed numerous challenges in scheduling a first-time appointment to receive medications for opioid use disorder, including finding a provider who takes insurance rather than cash.

The “secret shopper” study used trained actors attempting to get into treatment with an addiction provider in 10 U.S. states. The results, with more than 10,000 unique patients, revealed numerous challenges in scheduling a first-time appointment to receive medications for opioid use disorder, including finding a provider who takes insurance rather than cash.

Rutgers Toxicologist Warns About TikTok “Benadryl Challenge” Sending Teens to the ER

Economists conclude opioid crisis responsible for millions of children living apart from parents

Affiliates with Notre Dame’s Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities found that greater exposure to the opioid crisis increases the chance that a child’s mother or father is absent from the household and increases the likelihood that he or she lives in a household headed by a grandparent.

Affiliates with Notre Dame’s Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities found that greater exposure to the opioid crisis increases the chance that a child’s mother or father is absent from the household and increases the likelihood that he or she lives in a household headed by a grandparent.

Negative side effects of opioids could be coming from users’ own immune systems (video)

Opioid users can develop chronic inflammation and heightened pain sensitivity. These side effects might stem from the body’s own immune system, which can make antibodies against the drugs. The researchers will present their results at the American Chemical Society Fall 2020 Virtual Meeting & Expo.

American Chemical Society Fall 2020 Virtual Meeting Press Conference Schedule

Watch live and recorded press conferences at https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/pressroom/news-room/press-conferences.html. Press conferences will be held Monday, Aug. 17 through Thursday, Aug. 20, 2020