August 2020 has been a devastating month across large swaths of the United States: As powerful Hurricane Laura barreled into the U.S. Gulf Coast on August 27, fires continued to blaze in California. Meanwhile, farmers are still assessing widespread damage to crops in the Midwest following an Aug. 10 “derecho,” a sudden, hurricane-force windstorm.

Each of these extreme weather events was the result of a particular set of atmospheric — and in the case of Laura, oceanic — conditions. In part, it’s just bad luck that the United States is being slammed with these events back-to-back-to-back. But for some of these events, such as intense hurricanes and more frequent wildfires, scientists have long warned that climate change has been setting the stage for disaster.

Science News takes a closer look at what causes these kinds of extreme weather events, and the extent to which human-caused climate change may be playing a role in each of them.

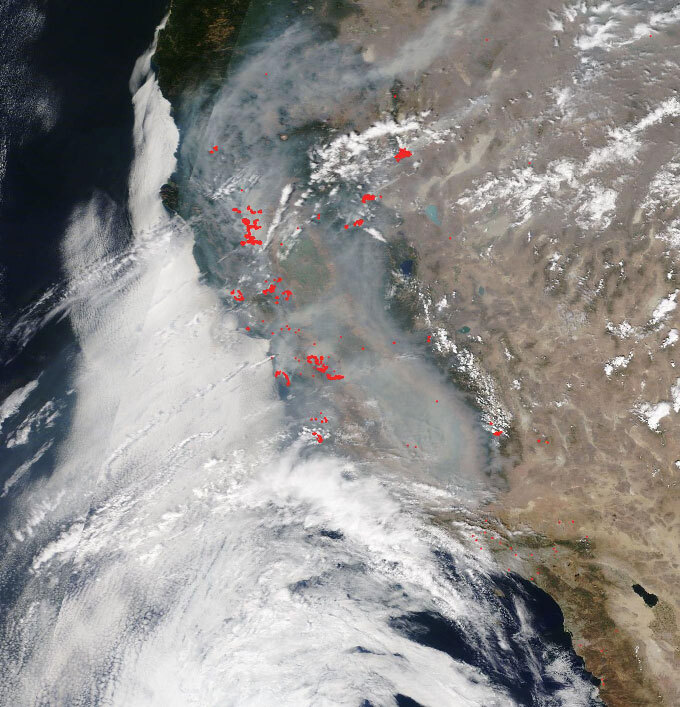

California wildfires

A “dry lightning” storm, which produced nearly 11,000 bursts of lightning between August 15 and August 19, set off devastating wildfires in across California. To date, these fires have burned more than 520,000 hectares.

That is “an unbelievable number to say out loud, even in the last few years,” says climate scientist Daniel Swain, of the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA.

The storm itself was the result of a particular, unusual set of circumstances. But the region was already primed for fires, the stage set by a prolonged and record-breaking heat wave in the western United States — including one of the hottest temperatures ever measured on Earth, at Death Valley, Calif. — as well as extreme dryness in the region (SN: 8/17/20). And those conditions bear the fingerprints of climate change, Swain says.

The extreme dryness is particularly key, he adds. “It’s not just incremental; it absolutely matters how dry it is. You don’t just flip a switch from dry enough to burn to not dry enough to burn. There’s a wide gradient up to dry enough to burn explosively.”

Both California’s average heat and dryness have become more severe due to climate change, dramatically increasing the likelihood of extreme wildfires. In an Aug. 20 study in Environmental Research Letters, Swain and colleagues noted that over the last 40 years, average autumn temperatures increased across the state by about 1 degree Celsius, and statewide precipitation dropped by about 30 percent. That, in turn, has more than doubled the number of autumn days with extreme fire weather conditions since the early 1980s, they found.

Although fall fires in California tend to be more wind-driven, and summertime fires more heat-driven, studies show that the fingerprint of climate change is present in both, Swain says. “A lot of it is very consistent with the long-term picture that scientists were suggesting would evolve.”

Though the stage had been set by the climate, the particular trigger for the latest fires was a “dry lightning” storm that resulted from a strange confluence of two key conditions, each in itself rare for the region and time of year. “’Freak storm’ would not be too far off,” Swain says.

The first was a plume of moisture from Tropical Storm Fausto, far to the south, which managed to travel north to California on the wind and provide just enough moisture to form clouds. The second was a small atmospheric ripple, the remnants of an old thunderstorm complex in the Sonoran Desert. That ripple, Swain says, was just enough to kick-start mixing in the atmosphere; such vertical motion is the key to thunderstorms. The resulting clouds were stormy but very high, their bases at least 3,000 meters aboveground. They produced plenty of lightning, but most rain would have evaporated during the long dry journey down.

Possible links between climate change and the conditions that led to such a dry lightning storm would be “very hard to disentangle,” Swain says. “The conditions are rare to begin with, and not well modeled from a weather perspective.”

But, he adds, “we know there’s a climate signal in the background conditions that allowed that rare event to have the outcome it did.”

Midwest derecho

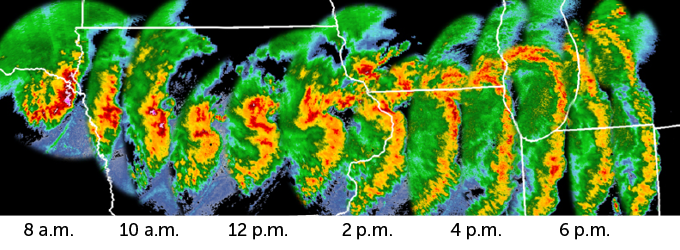

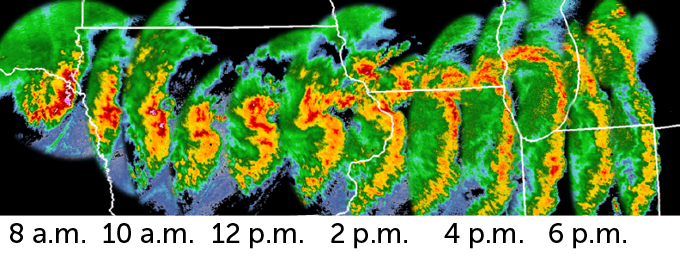

On August 10, a powerful windstorm with the ferocity of a hurricane traveled over 1,200 kilometers in just 14 hours, leaving a path of destruction from eastern South Dakota to western Ohio.

The storm was what’s known as a derecho, roughly translating to “straight ahead.” These storms have winds rivaling the strength of a hurricane or tornado, but push forward in one direction instead of rotating. By definition, a derecho produces sustained winds of at least 93 kilometers per hour (similar to the fury of tropical storm-force winds), nearly continuously, for at least 400 kilometers. Their power is equally devastating: The August derecho flattened millions of hectares of crops, uprooted trees, damaged homes, flipped trucks and left hundreds of thousands of people without power.

The Midwest has had many derechos before, says Alan Czarnetzki, a meteorologist at the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls. What made this one significant and unusual was its intensity and scale — and, Czarnetzki notes, the fact that it took even researchers by surprise.

Derechos originate within a mesoscale convective system — a vast, organized system of thunderclouds that are the basic building block for many different kinds of storms, including hurricanes and tornadoes. Unlike the better-known rotating supercells, however, derechos form from long bands of swiftly moving thunderstorms, sometimes called squall lines. In hindsight, derechos are easy to recognize. In addition to the length and strength conditions, derechos acquire a distinctive bowlike shape on radar images; this one appeared as though the storm was aiming its arrow eastward.

But the storms are much more difficult to forecast, because the conditions that can lead them to form can be very subtle. And there’s overall less research on these storms than on their more dramatic cousins, tornadoes. “We have to rely on situational awareness,” Czarnetzki says. “Like people, sometimes you can have an exceptional storm arise from very humble origins.”

The Aug. 10 derecho was particularly long and strong, with sustained winds in some places of up to 160 kilometers per hour (100 miles an hour). Still, such a strong derecho is not unheard of, Czarnetzki says. “It’s probably every 10 years you’d see something this strong.”

Whether such strong derechos might become more, or less, common due to climate change is difficult to say, however. Some anticipated effects of climate change, such as warming at the planet’s surface, could increase the likelihood of more and stronger derechos by increasing atmospheric instability. But warming higher in the atmosphere, also a possible result of climate change, could similarly increase atmospheric stability, Czarnetzki says. “It’s a straightforward question with an uncertain answer.”

Atlantic hurricanes

Hurricane Laura roared ashore in Louisiana in the early morning hours of August 27 as a Category 4 hurricane, with sustained winds of about 240 kilometers per hour (150 miles per hour). Just two days earlier, the storm had been a Category 1. But in the mere 24 hours from August 25 to August 26, the storm rapidly intensified, supercharged by warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic hurricane season is already setting several new records, with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration predicting as many as 25 named storms, the most the agency has ever anticipated (SN: 8/7/20).

At present, 2005 still holds the record for the most named storms to actually form in the Atlantic in a given season, at 28 (SN: 8/22/18). But 2020 may yet surpass that record. By August 26, 13 named storms had already formed in the Atlantic, the most ever before September.

The previous week, researchers pondered whether another highly unusual set of circumstances might be in the offing. As Laura’s track shifted southward, away from Florida, tropical storm Marco appeared to be on track to enter the Gulf of Mexico right behind it. That might have induced a type of physical interaction known as a Fujiwhara effect, in which a strong storm might strengthen further as it absorbs the energy of a lesser storm. In perhaps a stroke of good luck in the midst of this string of weather extremes, Marco dissipated instead.

As Hurricane Laura approached landfall, the U.S. National Hurricane Center warned that “unsurvivable” storm surges of up to five meters could inundate the Gulf Coast in parts of Texas and Louisiana. Storm surge is the height to which the seawater level rises as a result of a storm, on top of the normal tidal level.

It’s impossible to attribute the fury of any one storm to climate change, but scientists have observed a statistically significant link between warmer waters and hurricane intensity. Warm waters in the Atlantic Ocean, the result of climate change, juiced up 2017’s hurricanes, including Irma and Maria, researchers have found (SN: 9/28/18).

And the Gulf of Mexico’s bathlike waters have notably supercharged several hurricanes in recent years. In 2018, for example, Hurricane Michael intensified rapidly before slamming into the Florida panhandle (SN: 10/10/18). And in 2005, hurricanes Katrina and Rita did the same before making landfall (SN: 9/13/05).

As for Laura, one contributing factor to its rapid intensification was a drop in wind shear as it spun through the Gulf. Wind shear, a change in the speed and/or direction of winds with height, can disrupt a storm’s structure, robbing it of some of its power. But the Gulf’s warmer-than-average waters, which in some locations approached 32.2° C (90° Fahrenheit), were also key to the storm’s sudden strength. And, by warming the oceans, climate change is also setting the stage for supercharged storms, scientists say.

In a study, a team of Penn State researchers report that an algorithm they developed may be able to spot illicit online pharmacies that could be providing customers with substandard medications without their knowledge, among other potential problems.

In a study, a team of Penn State researchers report that an algorithm they developed may be able to spot illicit online pharmacies that could be providing customers with substandard medications without their knowledge, among other potential problems.