A new report from researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health offers recommendations aimed at federal, state, and local policymakers to address the opioid epidemic during the pandemic.

Category: Uncategorized

Climate warming linked to tree leaf unfolding and flowering growing apart

An international team of researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Zhejiang A & F University and the University of Eastern Finland have found that regardless of whether flowering or leaf unfolding occurred first in a species, the first event advanced more than the second over the last seven decades.

Wildfires, heat waves and hurricanes broke all kinds of records in 2020

2020 was a year of unremitting extreme climate events, from heat waves to wildfires to hurricanes, many of which scientists have directly linked to human-caused climate change (SN: 8/27/20). Each event has taken a huge toll in lives lost and damages incurred. As of early October, the United States alone had weathered at least 16 climate- or weather-related disasters each costing more than $1 billion. The price tags of the late-season hurricanes Delta, Zeta and Eta could push the final 2020 tally of such expensive disasters even higher, setting a new record.

With the COVID-19 pandemic dominating the news, some of these events may have already faded into memory. Here, Science News takes a look at this year of climate extremes.

Australia’s ‘black summer’

The bushfires that burned southeastern Australia between July 2019 and March 2020 scorched roughly 11 million hectares and killed dozens of people. Climate change made those devastating fires at least 30 percent more likely to occur, researchers reported (SN: 3/4/20). The primary reason: a prolonged and severe heat wave that baked the country in 2019 and 2020, which itself was exacerbated by climate change.

The intensity of Australia’s fires produced some striking sights. A particularly intense fire led to the formation of towering pyrocumulonimbus clouds that launched hundreds of thousands of metric tons of smoke into the stratosphere (SN: 6/15/20).

One massive plume of smoke, wrapped in rotating winds, ascended to a record 31 kilometers in the atmosphere, deep into Earth’s protective ozone layer. Although it’s not clear what chemical scars it left, such a large smoke plume has the potential to trigger chemical reactions that destroy ozone.

The West on fire

Record-setting wildfires in the U.S. West also produced heartbreaking images: raging blazes, orange skies, destroyed homes, neighborhoods enveloped in acrid smoke (SN: 9/18/20). By mid-November, more than 9,200 fires in California had burned about 1.7 million hectares — more than double the acreage burned in 2018, the state’s previous record fire year. Meanwhile, Colorado battled three of the largest wildfires in the state’s history. Combined, those fires burned more than 219,000 hectares.

The role of climate change in these blazes is multipronged. From California to Colorado, rising temperatures due to climate change have led to earlier spring snow melting, resulting in drier vegetation by summer. In California, that extremely dry vegetation combined with a record-breaking heat wave primed the landscape for runaway fires (SN: 8/17/20).

Climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme climate conditions. California’s average heat and dryness in both summer and autumn have become more severe, dramatically increasing the number of days each year prone to extreme fire weather conditions (SN: 8/27/20). Simulations of future climate change project increasing dryness over at least the next few decades — which means 2020’s fire records aren’t likely to stand for long.

Siberian meltdown

From January through July, Siberia was in the grips of a powerful heat wave that led to record-breaking temperatures (SN: 6/23/20), unprecedented wildfires in the Arctic and thawing permafrost, which in turn may have led to the collapse of a fuel storage tank that flooded nearby rivers with diesel fuel (SN: 7/1/20).

Such heat in Siberia — with temperatures as high as 38° Celsius (about 100° Fahrenheit) — would have been impossible without climate change (SN: 7/15/20). Human influence made the heat wave at least 600 times as likely — and possibly as much as 99,000 times as likely, scientists reported. Moreover, the carbon dioxide churned into the atmosphere by this year’s Arctic wildfires also smashed the previous record for the region, set in 2019 (SN: 8/2/19). That CO2 can beget further warming, and the fires can also speed up permafrost thaw, which could add more of another greenhouse gas, methane, to the atmosphere.

This year also saw the second-lowest extent of Arctic sea ice on record. Meanwhile, a roughly Manhattan-sized chunk of Canada’s Milne ice shelf — close to half of what had been the country’s last intact ice shelf — suddenly collapsed into the Arctic Ocean in August, carrying an ice-observing station away with it.

Supercharged hurricanes

As early as April, scientists predicted that the Atlantic hurricane season, which lasts from June 1 through November 30, would be busy, with about 18 named storms, compared with an average of 12 (SN: 4/16/20). By August, scientists upped their predictions to as many as 25 (SN: 8/7/20). But 2020 surpassed those expectations too: By mid-November, there were 30 named storms, eclipsing a record set in 2005 (SN: 11/10/20).

It’s difficult to link climate change to the number of storms that form in a given year. Very warm ocean waters, such as in the Atlantic Ocean this year, foster tropical cyclone formation. It’s true that those warm waters are linked to climate change, as the surface ocean swallows up excess heat from the atmosphere. But other factors are also involved in hurricane formation, including wind conditions, making it difficult to establish a link.

But there are established links between warming oceans and increasing hurricane intensity, as well as rainfall (SN: 9/13/18). Warm Atlantic waters gave a boost to the intense storms of the 2017 hurricane season, for example (SN: 9/28/18). The warm waters can also provide enough energy to give hurricanes extra staying power even after landfall (SN: 11/11/20).

And, as the world saw in 2020, very warm ocean waters can also speed up how quickly a storm strengthens — leading to dangerous, difficult-to-predict, suddenly supercharged storms. Such rapid intensification is defined as sustained wind speeds increasing by at least 55 kilometers per hour within just 24 hours. 2020 saw that in abundance, with 10 Atlantic storms rapidly intensifying in the region’s bathlike waters before making landfall.

Pandemic has severely disrupted sleep, increasing stress and medication use

The COVID-19 pandemic is seriously affecting the sleep habits of half of those surveyed in a new study from The Royal and the University of Ottawa, leading to further stress and anxiety plus further dependence on sleep medication.

Meet 5 Black researchers fighting for diversity and equity in science

As the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum this year, Black scientists jumped in to call for inclusivity at school and work.

Within days of the news that a Black bird watcher, Christian Cooper, had been harassed in New York City’s Central Park, the social media campaign #BlackBirdersWeek was launched (SN Online: 6/4/20), followed closely by #BlackInNeuro, #BlackInSciComm and many others.

Young scientists led many of these efforts to make change happen. Science News talked with some of these new leaders, as well as a few researchers who have been pushing for diversity in the sciences for years and see new opportunities for progress.

The following conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Deja PerkinsJason Ward

Deja Perkins

Urban ecologist

North Carolina State University

President, BlackAFinSTEM

Co-organizer, #BlackBirdersWeek

What prompted you to act?

After the May 25 incident that happened to Christian Cooper, Anna Gifty, another member of BlackAFinSTEM [a collective of Black professionals working across STEM fields], thought that it would be wise to highlight other Black birders. BlackAFinSTEM organized a week of events within about 48 hours. It was a good way to capture the momentum and bring attention to the experience of Black people outdoors. Any one of us could have been Christian Cooper. A lot of BlackAFinSTEM members have experienced racism in the field or have had negative experiences with the police.

What makes this year’s diversity initiatives different?

The collective effort of all of these events — #BlackHikersWeek, #BlackBotanistsWeek, #BlackInNationalParks, #BlackInNeuroWeek — is bringing more attention to the murders and harassment of Black people who are carrying out everyday tasks. These initiatives are making it easier for people who want to hop on board and make a difference.

Have you seen immediate effects?

Some organizations quickly responded to break down some of the barriers that prevent Black and Indigenous people from entering into the environmental space. The Free Binoculars for Black Birders campaign provided binoculars to anyone who identified as Black and wanted a pair of binoculars, and a similar campaign launched specifically for kids. Some organizations, such as the Wilson Ornithological Society, offered free memberships. And we have seen an increase in organizations reaching out to BlackAFinSTEM to hire some of our members for presentations, workshops and program development.

What could get in the way of lasting change?

One barrier I can foresee is gatekeeping. It’s still on a lot of organizations, nonprofits and government agencies to hire qualified Black professionals. Those groups hold the power for change, and so they have to take the initiative to hire qualified individuals.

With #BlackBirdersWeek and BlackAFinSTEM, we have been creating our own table to get more people engaged and involved in the outdoors. But we can only do so much. It really comes down to partnerships, working with other established organizations to continue to make change. — Carolyn Wilke

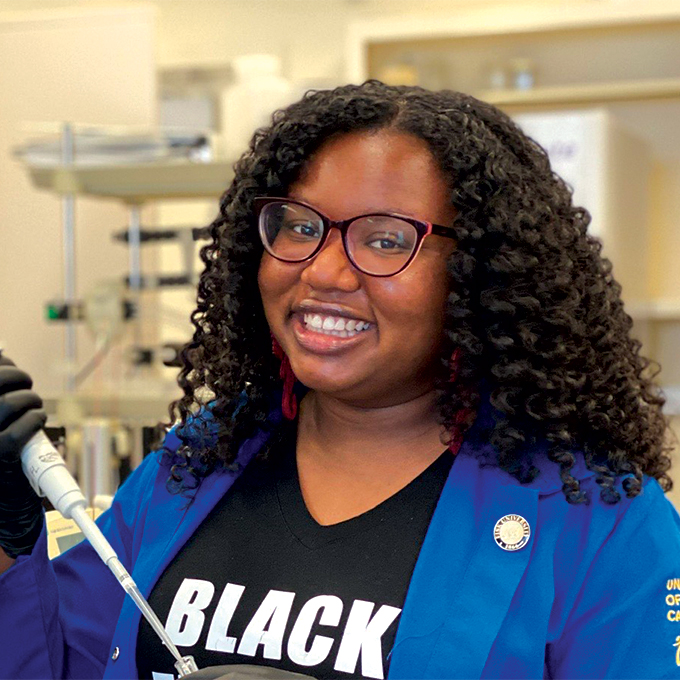

Raven Baxter

Science education graduate student

University at Buffalo

Raven the Science Maven on YouTube

Founder, @BlackInSciComm

What prompted you to act?

I founded #BlackInSciComm out of the need for Black voices in the science space. This year has been very hard for many, but particularly for Black people. And we’ve been feeling like Black science communicators have been using their voices advocating for racial justice and for their lives and for their freedom. That comes at a great price. They are sacrificing their voices in science to make sure that people understand that their lives matter. And, you know, that shouldn’t even have to be the case.

What makes this year’s diversity initiatives different?

We saw the importance of owning our own narrative. That’s why we’re seeing so many “Black in X” movements. Everybody is unique and doing special work. It should all be celebrated.

What long-term effects do you envision?

I think it’s going to be amazing for future generations. One of the biggest issues that marginalized folks have is imposter syndrome — the product of not feeling like you belong because you don’t see anybody like you in your field. So you’re doing well and you’re succeeding, but you feel like you’re an imposter because the narrative that’s been pushed for so long is that we’re not in these fields or that we don’t do well in these fields. But that’s not true.

How do this year’s efforts make you feel?

We’re setting roots that spread a message that Black people do belong in things, and building up new generations of STEM professionals. I can tell that people want to support and amplify Black voices and invest in the community and it’s so cool. I just feel very loved, and I feel like we are giving love. — Bethany Brookshire

Brian Nord

Cosmologist

Fermilab

Co-organizer, Strike for Black Lives

What prompted you to act?

In early June, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein of the University of New Hampshire and I initiated the Strike for Black Lives. The Particles for Justice collective, a group of scientists who originally convened to condemn sexism in STEM, organized and promoted the strike very quickly.

I had worked for a long time within the institutionally paved pathways to make change, and I tried to make new pathways. But, when I looked around, I saw promises unkept and much work to be done. For years, there’s been way too few Black faculty in physics plus too little investment by academic institutions in Black communities. And there’s been little to no accountability for racist and misogynist behavior that drives Black people away from research. It’s time for these things to end. We needed to do something different.

What was the aim of the June 10 Strike for Black Lives?

The core objective was for non-Black scientists to stop doing science for a day and invest their time into building an antiracist, just research environment. For Black scientists and other academics, the day was intended for rest or doing the work they may not have otherwise had time to do. Often, when I spend time fighting racism in STEM, this is time that I don’t spend doing research or with family. That’s time that my white colleagues have to get research done.

I have the privilege to explore nature, to investigate and extend the edge of knowledge. How many more [people] have wanted to do this but have been denied the opportunity? I’m here to imagine and learn how the universe works. I’m also here to imagine and build just research communities, where Black people have the opportunity to pursue their cosmic dreams.

Have you seen any immediate effects from the strike?

I’ve seen many scientists begin to invest time in the study of racism, white supremacy, misogyny, and begin to observe how these forces permeate society — including the scientific community — to disenfranchise Black people and other people of color. I’ve also seen scientists begin to take action to deflate or confront these forces, and to start creating a just research environment. — Maria Temming

Angeline Dukes

Neuroscience graduate student

University of California, Irvine

Founder and president, @BlackInNeuro

What prompted you to act?

A lot of it was being one of two Black women in my department. It’s very isolating. Thank God I have her to talk to. But a lot of other Black students in neuroscience don’t even have that.

And we don’t have any Black faculty in our department. It’s not like we have someone who understands what it’s like to be a Black person and to be witnessing these brutal murders and all this police brutality. It’s emotionally and mentally draining, but we still have to be in the lab. And of course, it’s still a pandemic. There is so much going on.

Having a community who just gets it, and understands exactly what we’re going through and can support and uplift and just be there for us, is a major driving force in #BlackInNeuro. There are people out there who care about you and understand your experiences without you having to explain why you feel this way.

What initiative did you launch?

It started with a tweet: “Sooo when are we doing #BlackInNeuro week?” I didn’t expect to get a huge response. I didn’t have a huge following on Twitter. But a lot of people were very interested.

The same night I sent the tweet out, we made a Slack channel. We had about 22 people join. That was on Friday. By Sunday we had our first meeting. In about three weeks, we had organized the whole week [July 27 to August 2].

We got speakers and panelists from different career stages to talk about their experiences. We used hashtags to plan events and different ways of highlighting and amplifying Black voices and Black research and Black people in neuroscience-related fields. We want this to be a lasting thing. One week isn’t nearly enough for us to actually make a continuous change.

What makes #BlackInNeuro have such potential?

It is led by Black people for Black people. We are mostly graduate students and postdocs, so it’s a trainee-led initiative. There aren’t a lot of Black people in faculty positions. There are more of us at the graduate level. We have the energy and the drive to build a community and hopefully retain more of us in these fields so we can get those faculty positions.

What long-term effects do you envision?

The Society for Neuroscience meeting was canceled because of COVID. Black trainees would have used that as an opportunity to present their research. We held a mini-conference in late October to have a space for them to get that presentation experience and networking experience and professional development workshops.

How did this year’s efforts make you feel?

We did a #BlackInNeuro roll call [an invitation for people to share their own stories on social media]. What was really nice about that was seeing all the different Black neuroscientists, Black neuroengineers. Just seeing that there were so many Black people in this field was amazing to me.

We had a [virtual] social for Black women in neuro. It meant the world to me to be able to connect in that way with so many other Black women. I got to see them as people and not just names on paper. The whole week, I really loved all of it. — Laura Sanders

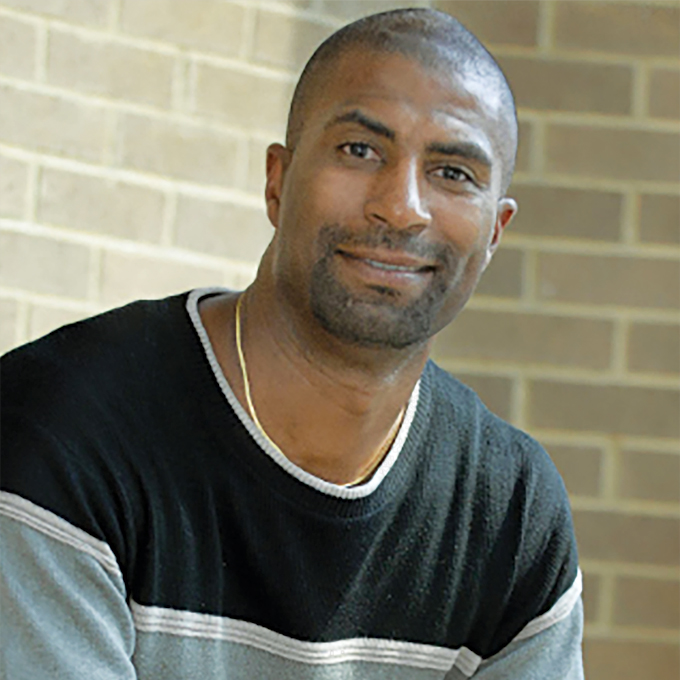

Gary Hoover

Economist

University of Oklahoma

Cochair, Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession, American Economic Association

What initiative have you been involved with?

For the last eight years, I have served as cochair of the Committee on the Status of Minority Groups in the Economics Profession. As such, I see all the data on minority representation and the number of minorities that we have in our field. That number always has been really, really low. In fact, economics has a lower percentage of minorities, or at least Blacks, than does pure mathematics. That is damning.

In early 2019, the American Economic Association sent out a survey about the state of our profession. The results showed that women and minorities didn’t feel good about things. My committee cochairs Ebonya Washington, Amanda Bayer and I realized that the survey only included people in the profession. For our survey, appearing in the Summer 2020 Journal of Economic Perspectives, we found people who had left the profession by looking at former participants in a decades-old summer program aimed at training undergraduates for careers in economics. Minority students didn’t always feel welcomed into the field. They weren’t told, “This is a big tent and there’s room for you here in this profession.”

What prompted you to act?

My first job out of graduate school was at the University of Alabama. I was the first Black tenure-track faculty member hired in the business school. Once I received tenure, around 2003, the university made me the assistant dean for faculty and graduate student development. My job was to recruit and retain Black faculty. By the time I left that job in 2014, the University of Alabama business school had more Black faculty and graduate students than all the other schools in the Southeast Conference combined. Since I left, those numbers have fallen off, which shows that we need active recruitment.

What makes this year’s diversity initiatives different?

Right after things blew up this summer with George Floyd’s death, the American Economic Association put out a statement about how much diversity and inclusiveness matters in our profession. Myself and Ebonya Washington, we said to them, “Statements aren’t enough. What are you going to do?”

We went to them with five actionable items, now permanent and annual parts of the American Economic Association initiatives for diversity and inclusion. One of the initiatives presents opportunities for underrepresented minorities to meet with a high-ranking person in the economics profession. We are talking about Ben Bernanke–type names, really high-profile economists. We succeeded because we went to the executive board with proposals already in hand.

What change would you like to see?

As economists, we know that if you want to change people’s behavior, you need incentives. For instance, we tell people they won’t get tenure if they don’t have a certain level and quantity of publications. That’s clearly written out and people know that and they respond by producing the quantity and quality of publications that are necessary. Why don’t we have that for diversity? If a school wants to diversify its econ department, it can say to the chair: “Your tenure status, your raises, your promotion are all tied to how well your department diversifies.” We can get what we’re looking for. It’s economics. It’s what we do. It works.

What is lost when minority voices aren’t at the table?

Policy makers come to economists for advice. But when you’ve got a sizable portion of your labor force of economists sitting it out because the climate isn’t inviting for them, then you can’t give good advice. What’s going to happen next is policy makers are going to start going to the fields that do give more inclusive advice. We’re just going to get left behind. — Sujata Gupta

These 6 graphs show that Black scientists are underrepresented at every level

Nationwide protests in response to the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other unarmed Black men and women in the first part of 2020 inspired calls to action within academia’s ivory tower.

Social media movements such as #BlackInSTEM brought attention to discrimination faced by Black students and professionals throughout the science, technology, engineering and mathematics pipelines. U.S. Black residents studying and working in STEM fields are underrepresented at every level, from undergraduate degree programs to the workforce.

The academic environment fails to support Black students, says economist Gary Hoover of the University of Oklahoma in Norman. “Black students in STEM are some of the most talented people around, and if the environment isn’t going to be welcoming, these folks just take their talents elsewhere.”

More U.S. students are getting science and engineering degrees than ever before. But the gap for Black students in these fields has been stubbornly wide, as population-adjusted figures show. In 2018, the most recent year for which data are available, about 238 of every 100,000 U.S. residents earned a STEM bachelor’s degree. If the Black community was adequately represented in STEM higher education, its rate would be similar – 238 of every 100,000 Black residents would have earned these degrees. Yet only 161 of every 100,000 Black residents had done so.

The gap continues into graduate school. In 2018, Black residents were 12.3 percent of the U.S. population, but only 8.4 percent of bachelor’s graduates, 8.3 percent of master’s graduates and 5.5 percent of doctoral graduates.

As Black STEM students make their way up the academic ladder, they may face learning and research environments that are unsupportive or actively hostile. In a 2018-2019 study by the American Institute of Physics, Black students in physics reported that they commonly experienced a lack of financial support, as well as microaggressions, small interactions in which peers or superiors question a person’s presence or performance due to racially charged bias. These experiences negatively affected the person’s sense of belonging in the field. The study results were based on a survey of 232 students, 53 percent of whom identified as Black or Black biracial. In the survey, 42 percent of the Black physics students reported that their department creates a supportive environment “most times,” compared with 53 percent of their white colleagues. Four percent of the Black students reported that their department “never” creates a supportive environment; none of the white students selected this response.

“As I reflect on my own academic journey… there were fewer and fewer Black students in my programs,” says anthropologist Stephanie Poindexter of the University of Buffalo in New York. Poindexter was one of very few Black students studying primates in her undergraduate program, and representation narrowed further as she progressed to a Ph.D. “What I see is a lot of untapped potential,” Poindexter days: “interested students of color who are not fostered into higher degrees in the same way that other students are fostered.”

Within the U.S. STEM workforce, Black scientists are also underrepresented, as are Hispanic or Latino and Native American scientists, according to 2017 data.

Among 11 STEM professions reviewed by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, or NCSES, only one field demonstrates a rate of Black representation that is close to the overall population: 92 of every 100,000 Black residents are social scientists, compared with 122 of every 100,000 U.S. residents overall.

The disparity is especially severe in engineering. For example, 29 of every 100,000 U.S. residents are chemical engineers compared with 2 of every 1000,000 Black residents.

“Young Black potential engineers have few role models that look like them and/or come from similar backgrounds that they can emulate, manifesting in a deficit in the younger students cultivating these skills,” says Aaron Kyle, senior lecturer in biomedical engineering design at Columbia University’s Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science. Kyle also notes that minority scientists may be cited less than their peers, leading to challenges in career advancement.

Disparities in salary are found in most, but not all, STEM fields. Computer science has the largest disparity, with a median annual salary in 2017 of $97,000 for white professionals compared with $72,000 for Black professionals. There are so few working Black mathematicians that the NCSES couldn’t even make a comparison.

Black scientists in the biological and social sciences, on the other hand, have higher median salaries than their white colleagues. Perhaps, Hoover says, some social sciences, such as political science, may be “more readily able and willing to embrace issues around ethnicity, race and inclusion” than other fields, allowing Black scientists to negotiate more equitable pay.

When Black students shift to other tracks, Black communities suffer from a lack of doctors, researchers and engineers who directly understand their experiences and needs. The loss leads to blind spots in innovation, Kyle says.

“We see clear examples of this, ranging from facial recognition software not accurately identifying Black faces all the way through race-based health care disparities: COVID-19 mortality, elevated maternal [death] in Black women, higher amputation levels amongst Black diabetics,” he says. For instance, the mortality rate for Black newborns was cut in half when the babies were cared for by Black doctors, according to a recent report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (SN: 8/25/20).

To improve Black representation in science, Poindexter, Hoover and Kyle all say that solutions must include new offerings of grants, promotions and other research programs dedicated to supporting Black STEM students from elementary school into the workforce. “There needs to be a concentrated effort and financial commitment to balance the scales in the next one to five years,” Poindexter says.

Small, quiet crickets turn leaves into megaphones to blare their mating call

The rules of the tree cricket world, sexually speaking, are simple.

Perched from a leaf’s edge, males call out into the night by rhythmically rubbing their wings. Females survey the soundscape, gravitating towards the loudest and largest males. Small, quiet types get drowned out.

Unless they cheat the system.

Some male crickets make their own megaphones by cutting wing-sized holes into the center of leaves. With their bodies stuck halfway through this vegetative speaker, male Oecanthus henryi crickets can more than double the volume of their calls, allowing naturally quiet males to attract as many females as loud males, researchers report December 16 in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

It’s a rare example of insect tool use that “really challenges you to think about what it takes to produce complex behavior,” says Marlene Zuk, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul who wasn’t involved in the study.

Biologists first spotted crickets creating leaf-speakers, called baffles, and singing from them, or baffling, in 1975. Since then, the baffling behavior has been reported in two other species, but wasn’t clear exactly how it benefits individual crickets.

Rittik Deb, an evolutionary ecologist at the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India, was stunned when he first witnessed an O. henryi male baffling. “It was mind-bogglingly beautiful,” he says, “I had to understand why it was happening.”

Deb and his colleagues first looked for any commonalities among crickets who use baffles. Only 25 out of 463, or 5 percent, of crickets observed and individually marked at field sites outside Bangalore were seen baffling. On average, baffling males were smaller, and called more quietly when not baffling. In the field, Deb found that baffling approximately doubles the volume of a quiet male’s call, raising them to the level of the most attractive males.

Cricket wings are essentially resonance structures, reverberating with the vibration caused by rubbing, sort of like the body of a violin (SN: 4/30/12). When bafflers crawl through a hole in a leaf, align their wings with the leaf and start to sing, they’re essentially expanding this resonance structure, using the leaf “a bit like a loudspeaker or a megaphone,” Deb says.

Do females fall for their inflated calls? Yes, according to lab experiments. When given a choice, females overwhelmingly prefer louder calls, even when these come from baffling males. Baffling essentially evens the playing field, allowing quiet males to attract just as many females as louder males.

The benefits of baffling don’t stop there.

The climax of cricket mating is the transfer of the spermatophore, a protein ball packed with sperm. Females dictate how much sperm they accept by how long they retain the spermatophore. With larger males, it’s about 40 minutes, compared with only 10 minutes for small males. But when Deb artificially boosted the calls of small and quiet males, females treated them like large males, retaining their spermatophores for longer. “That really surprised us,” Deb says. “It’s as though the females are in some sense being deceived.”

It’s unclear why females don’t seem to notice that they’re mating with a smaller male, though it’s not necessarily surprising. “They’re not wrapping their little arms around males to see whether they’re big or small,” Zuk says. “Maybe there’s something in the song that signals ‘go ahead and have more of this guy’s babies.’”

Whatever the mechanism, O. henryi males have evolved a remarkably effective mating strategy, Zuk says. The behavior appears to be innate, not learned, as lab-raised crickets of all sizes can make and use baffles when given leaves. “It makes me really want to know why such a small portion of males actually do this,” Zuk says.

Baffling might not be worth the extra work for larger males that can already attract plenty of females. But there are many small and quiet males who could presumably reap huge rewards by baffling, but don’t. Perhaps the crickets face a shortage of big enough leaves, or maybe baffling males face a trade-off: With their antennae blocked by the leaf, baffling could make crickets sitting ducks for predators such as geckos and spiders to attack from behind.

Despite potential costs, it’s clear these crickets have evolved a clever way of bending the natural world to their interests. Such tool use among animals is varied, from primates cracking nuts with stones to puffins scratching themselves with sticks (SN: 6/24/19;SN: 12/30/19). While some biologists may quibble with designating a baffle as a bona fide tool, these crickets show that sophisticated behaviors aren’t just for big, complex brains. “It really turns that idea on its head,” Deb says.

The Milky Way’s central black hole may have turned nearby red giant stars blue

Innumerable stars reside within 1.6 light-years of the Milky Way’s central black hole. But this same crowded neighborhood has fewer red giants — luminous stars that are large and cool — than expected.

Now astrophysicists have a new theory why: The supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*, launched a powerful jet of gas that ripped off the red giants’ outer layers. That transformed the stars into smaller red giants or stars that are hotter and bluer, Michal Zajaček, an astrophysicist at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, and colleagues suggest in a paper published online November 12 in Astrophysical Journal.

Today Sagittarius A* is quiet, but two enormous bubbles of gamma-ray-emitting gas rooted at the center of the Milky Way tower far above and below the galaxy’s plane (SN: 12/9/20). These gas bubbles imply the black hole sprang to life some 4 million years ago when something fell into it.

At that time, a disk of gas around the black hole shot a powerful jet of material into its star-studded neighborhood, Zajaček and colleagues propose. “The jet preferentially acts on large red giants,” he says. “They can be effectively ablated by the jet.” The biggest and brightest red giants seem to be missing near the galactic center, Zajaček says.

Red giants are vulnerable because they are large and their envelopes of gas tenuous. A red giant forms from a smaller star after the star’s center gets so full of helium that it can no longer burn its hydrogen fuel there. Instead, the star starts to burn hydrogen in a layer around the center, which makes the star’s outer layers expand, causing its surface to cool and turn red. As a result, some red giants are more than a hundred times the diameter of the sun, making them easy pickings for the jet.

Still, Zajaček says that as red giants orbit the black hole, they must pass through the jet hundreds or thousands of times before becoming hot, blue stars. The jet is most effective at removing red giants within 0.13 light-years of the black hole, the team calculates.

“The idea is plausible,” says Farhad Yusef-Zadeh, an astronomer at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., who was not involved with the study.

Tuan Do, an astronomer at UCLA, adds “it may take a combination of several of these kinds of mechanisms to fully explain the lack of the red giants.” In particular, he says, something other than a jet likely accounts for the paucity of red giants farther away from the black hole.

One candidate, say Zajaček and Do, is a large disk of gas that circled the black hole a few million years ago. This disk spawned stars that now orbit the black hole in a single plane. These young stars exist as far as 1.6 light-years from the black hole, which is also the extent of the red giant gap. As red giants revolved around the black hole and repeatedly plunged through the disk, its gas may have torn off their outer layers, explaining another part of the galactic center’s red star shortage.

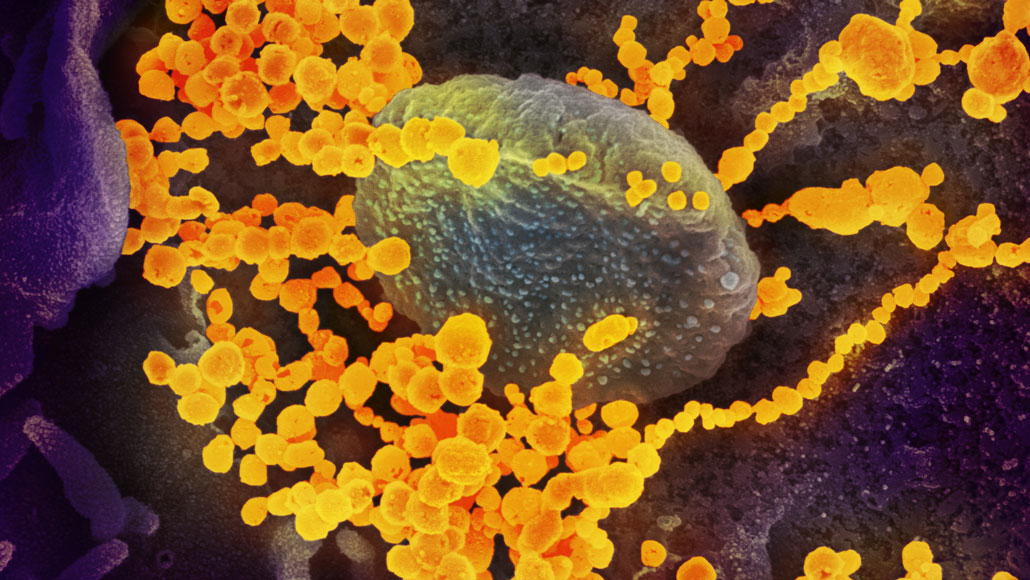

This COVID-19 pandemic timeline shows how fast the coronavirus took over our lives

Few people noticed on New Year’s Eve last year when China reported a mystery illness to the World Health Organization. But soon, the never-before-seen coronavirus responsible for the disease was infiltrating the rest of the world.

As we prepare to enter the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Science News looks back on how the disease took over 2020 and how society attempted to fight back.

December 31, 2019

China notifies the World Health Organization about a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown cause in Wuhan.

January 9, 2020

The WHO announces a novel coronavirus is the cause of the pneumonia.

January 10

Scientists release the virus’s complete genetic blueprint.

January 13

Thailand reports the first known novel coronavirus infection outside of China. Within a week, Japan and South Korea report cases.

January 21

The first U.S. infection is reported in the state of Washington.

Scientists announce the virus can spread person-to-person.

January 23

Wuhan goes into lockdown to stem the virus’ spread.

January 24

France reports the first cases in Europe.

January 25

Australia reports its first case.

January 30

Scientists say an infected person spread the virus before showing symptoms.

February 3

The Diamond Princess cruise ship is quarantined in Japan. Eventually, 712 of the 3,711 people on board test positive. Through mid-March, cruise ship travelers represent about 17 percent of known U.S. cases.

February 5

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention releases a flawed COVID-19 diagnostic test, delaying the country’s ability to screen widely for the virus.

February 11

Virologists name the virus “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” or SARS-CoV-2, because it is related to the virus that caused the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak. The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is named “COVID-19.”

February 14

Egypt reports Africa’s first case.

February 26

Brazil reports South America’s first case.

March 9

Italy begins a national lockdown. Ten days later, the country’s COVID-19 deaths top 3,400, surpassing China’s death toll.

March 10

After a choir in Washington state meets for a practice, over 80 percent of attendees get infected, suggesting airborne transmission of the virus.

March 11

The WHO declares the outbreak is a pandemic. The virus has spread to at least 114 countries, killed over 4,000 people and infected nearly 120,000.

March 16

COVID-19 vaccine safety tests begin in the United States and in China.

March 17

Contrary to conspiracy theories, a study confirms the virus was not made in or released from a lab. Subsequent research suggests a bat is the most likely source.

March 19

California issues the first statewide stay-at-home order.

March 27

As the number of U.S. cases surpasses 100,000, the United States becomes the new epicenter of the pandemic.

March 28

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration grants emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine, an antimalaria drug, to treat some hospitalized patients.

April 2

Global cases hit 1 million. More than 53,000 people have died.

April 3

With evidence mounting that the virus can spread through the air and that asymptomatic people are contagious, the CDC recommends people wear face coverings in public.

April 11

U.S. death toll hits 20,000 people, surpassing the number of deaths in Italy.

April 28

U.S. cases reach 1 million.

May 1

The FDA grants emergency use authorization for the antiviral drug remdesivir for severely ill patients after preliminary findings suggest the drug can shorten hospital stays.

May 14

The CDC sends out an advisory about cases of a multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children who test positive for the virus.

June 15

The FDA revokes emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine after multiple studies show no benefit.

June 16

Dexamethasone, a steroid, is the first drug found to reduce COVID-19 deaths, among people sick enough to need respiratory support.

June 25

China approves a vaccine for use by the military, before final safety and efficacy testing is completed.

June 28

Less than six months after the disease is named, more than 10 million people worldwide have been infected with the virus and over 500,000 have died.

July 10

Gilead Sciences, the maker of remdesivir, claims the drug reduces risk of death from COVID-19.

July 27

Pfizer and Moderna begin recruiting tens of thousands of volunteers for late-phase clinical trials of their vaccines.

August 11

Russian President Vladimir Putin announces that a vaccine dubbed Sputnik V will be available to the general public, even though all phases of testing are not yet completed.

August 17

A week into the fall semester, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announces all undergraduate classes will move online because of high infection rates on campus.

August 23

The FDA grants emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma to treat hospitalized patients, despite a lack of clinical trials assessing whether blood from recovered patients actually helps fight the disease.

August 25

The first report of a person being reinfected with the virus raises concerns about how long immunity lasts.

September 28

More than 1 million people have died from COVID-19; over 40 percent of deaths have occurred in the United States, Brazil and India.

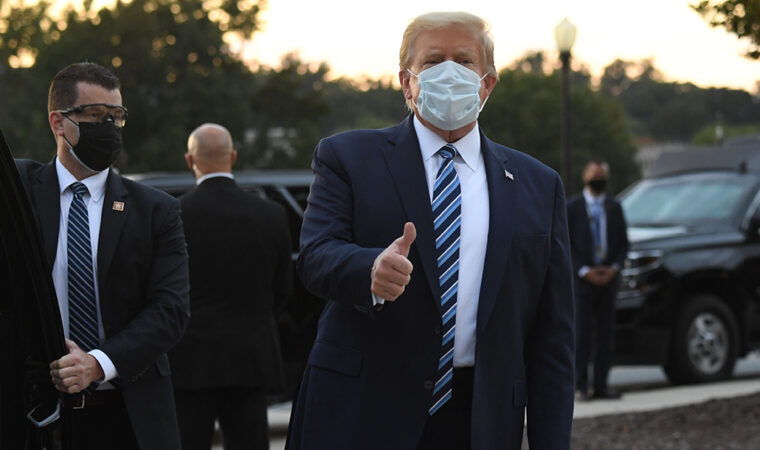

October 2

President Donald Trump tweets that he is infected, becoming the latest in a series of world leaders to get COVID-19. He is later hospitalized and receives remdesivir, dexamethasone and an experimental antibody treatment.

October 22

Remdesivir becomes the first drug to win full FDA approval for treating COVID-19. A week earlier, however, a WHO study found that the drug does not reduce COVID-19 deaths, countering the drugmaker’s earlier claim.

October 23

Researchers report that Hispanic and Black residents are disproportionately represented among U.S. COVID-19 deaths. From May through August, Hispanic or Latino people accounted for 24.2 percent of the total deaths. Non-Hispanic Black people accounted for 18.7 percent of the deaths.

November 9

Based on preliminary data, Pfizer says its vaccine appears to be 90 percent effective at preventing people from getting sick from the coronavirus. Subsequent findings suggest 95 percent effectiveness.

The FDA grants emergency use authorization for Eli Lilly’s monoclonal antibody therapy. The lab-made antibodies may keep virus levels low in newly infected people and prevent hospitalizations.

November 16

Moderna says its vaccine is 95 percent effective.

November 20

Pfizer seeks emergency FDA approval for its vaccine. Ten days later, Moderna requests the same.

November 23

AstraZeneca reports its vaccine is 62 to 90 percent effective.

December 2

The United Kingdom clears Pfizer’s vaccine for emergency use.

December 10

An advisory committee recommends that the FDA grant emergency use authorization of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine.

Global cases stand at more than 69 million, with more than 1.5 million deaths.

Hear from people taking action against COVID-19

As the coronavirus pandemic picked up speed this year, some people’s jobs became a nonstop race to help save lives. Here, an emergency medicine doctor, vaccine trial volunteer, protective equipment manufacturer, public health director and others share what 2020 was like for them.

The following interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Yvette Calderon is chair of emergency medicine at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital. She was on the front lines of New York’s City’s early pandemic surge.

Q: How did the pandemic change your work?

Calderon: It was a very stressful time. it was really important to check in with everyone — nursing staff, faculty, residents, the [physician’s assistants] — just to make sure we had a mental health check. We saw a lot of death, more than I’ve ever seen in a short period of time.

Q: Tell us about your experience.

Calderon: It was very isolating. You saw the fear on everyone’s face, not only the patients, but your peers, your staff. It was just incredibly tense. Yet there was nowhere else that I wanted to be.

Q: What surprised you about the public’s response to the pandemic?

Calderon: Nothing. New Yorkers are awesome. How New Yorkers came together in this crisis, from the 7 o’clock clapping to people going out of their way with food for health providers, making sure that the elderly had [what they needed], kids creating incredible masks and shields for our essential workers.

Q: What has made your job hard?

Calderon: Not knowing. I haven’t seen my mom in several months and I lost my father [to COVID] on April 6. Both of them had COVID. I made an appointment to see [Mom] this week. But [the nursing facility] can call me and say there’s another outbreak and then I can’t see her.

To be a physician that has spent your whole life taking care of patients, holding patients’ hands when they’re at the end of their life, crying with the patient’s family, and to not be able to be with my father was the biggest heartbreak of all.

Q: What gives you hope for the future?

Calderon: Several colleges and medical schools have reached out to me to do presentations on health disparities. What gives me hope is how many incredibly bright, passionate young individuals want to understand [why certain groups are getting more seriously ill]. And actually want to do something about it.

Abigail Echo-Hawk, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma, is chief research officer at the Seattle Indian Health Board, a federally qualified health center that serves American Indians and Alaska Natives in the Puget Sound region. As director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, she focuses on gathering data on the more than 70 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives who live off tribal reservation lands, and whose information is rarely collected or analyzed, making COVID-19 resource allocation difficult.

Q: How has the pandemic changed your work?

Echo-Hawk: I had to take my staff and redirect them, which means that work we’re doing on cancer prevention and HIV prevention is going to suffer. HIV is an epidemic within our community. But right now, COVID-19 is killing our people every single day.

Q: What do you want people to know about your experience?

Echo-Hawk: We are really suffering from a lack of resources, and that suffering is not new. As a result of the continuous underfunding of public health infrastructure within the Native community, and all public health infrastructure, this country set up a perfect environment for a pandemic to run wild.

Q: What has surprised you about the public’s response?

Echo-Hawk: Some tribal nations made incredible public health decisions before states did, before counties did, before cities did. They closed off their reservations, they shut down businesses, they worked to put together support systems to take care of their elders.

Q: What one thing is making your job hard?

Echo-Hawk: Access to good-quality data. We know that people of color are more at risk for COVID and for mortality from COVID. It is going to be imperative to prioritize folks who are most at risk for getting [a] vaccine. How are we going to know that those priority populations are actually the ones getting that vaccine?

Q: What gives you hope?

Echo-Hawk: Because of the pandemic, along with all the other things that have happened on addressing racial justice within the United States, there is a level of awareness in the U.S. about racial disparities, in health, in policing. It’s given me hope for the future, that we can build a new normal where all people have equal value and equal worth.

Dale Chappell is chief scientific officer of Humanigen, a biotech company in Burlingame, Calif., that makes the monoclonal antibody lenzilumab, developed to prevent an immune system overreaction known as a cytokine storm. The drug is in Phase II and Phase III clinical trials against COVID-19. Chappell is currently based outside Geneva.

Q: How has the pandemic changed your work?

Chappell: I’m a scientist by training, but I came to biotechnology initially as an investor. I joined the Humanigen board and then after discussion with the board and management team I became the full-time chief scientific officer. [With the pandemic,] I’ve dedicated full time to lenzilumab, making sure we can get this drug to patients as quickly as possible.

Q: How did your training prepare you to fight the pandemic?

Chappell: After medical school I did a postdoc fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., and I studied [granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor], an immune system chemical that initiates the cytokine storm that can [occur] in COVID-19. So for me, this has come full circle. This is exactly what I should be doing at this moment in time.

Q: What have you learned?

Chappell: It’s been really interesting to watch the global pharma and biotech community all come together to try to address this pandemic. The information-sharing. The fact that people are willing to put their data out on preprint servers.

Q: What has surprised you about the public’s response?

Chappell: I’m living in Switzerland. The initial [European] lockdowns and quarantines [were] a pretty amazing act of humanity by everyone to try to flatten the curve, to keep the hospitals from being overrun.

Q: What is making your job hard to do?

Chappell: As a small company trying to take on a global pandemic, it’s always resources. We could use more people, we could use more clinical trial sites. We can’t get data fast enough. We need more hours in the day.

Q: What gives you hope for the future?

Chappell: The way governments around the world, and the biopharma industry, the way they’ve all come together to tackle this pandemic. We’ve learned a dramatic amount. In six, 12, 18 months’ time, I think we’re going to know a lot more. And hopefully, life will start to look a little more normal.

Q: What do you miss about your old life?

Chappell: The human interaction with colleagues. Going to scientific conferences, having that personal interaction. It’s tough to do by Zoom.

Michael Bowen is executive vice president of Prestige Ameritech in North Richland Hills, Texas, a maker of surgical masks and respirators. He predicted that a future epidemic would eat up U.S. supplies of personal protective equipment because most PPE is made in other countries.

Q: How has the pandemic changed your life?

Bowen: We work all the time, my business partner and I. I am the face of the company; I have the easy job. He is literally living at the office: He has an RV parked there and goes home only on weekends. Our sales have increased 600 percent. We’ve grown from 80 people to 260. We were selling 75,000 respirators per month. We’re now selling 5 million per month. By January or February we’ll be making 10 million a month.

Q: What do you want people to know about your experience?

Bowen: I’ve gotten thousands of emails in a day: “My daughter is a nurse and she’s been wearing the same mask for 30 days. Can you help me?” It was heartbreaking. I want people to know that America needs to make its own products.

Q: What have you learned during the pandemic?

Bowen: That humans aren’t very good at preparing for things. After this is over, people are going to forget. Hospitals are going to think: What are the odds of it happening again? I went through this before, in [the 2009] H1N1 [avian flu pandemic]. We had people calling, very emotional: I need help, we need masks. And then they didn’t stick with us.

Q: What do you miss about your old life?

Bowen: The ability to make everyone who calls me happy. We had great products and we served people right and if they had a problem or ran out of product we would put it in a truck and drive it there. I can’t do that anymore. I can’t help everyone.

Lisa Fitzpatrick is a clinical professor of medicine at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, D.C. She launched the company Grapevine Health to promote health literacy. She is also a coronavirus vaccine trial volunteer.

Q: What do you want people to know?

Fitzpatrick: I want people to know it’s always relevant to connect and listen to people. More than ever, the pandemic is showing how disconnected we are. The things I’m hearing on the street — is 5G transmitting coronavirus? Is there a chip in the vaccine? Is coronavirus real? — people are so distrustful of government and the health care system.

Q: Why did you join a vaccine trial?

Fitzpatrick: One day, a gentleman said he didn’t want to have anything to do with Trump’s vaccine. When I asked him what would have to happen for him to decide to take the vaccine, he said, “I would consider it if I saw some other Black people working on it.” And I thought, well, I’ve been a research investigator. I’m a Black woman. I’m a physician. I can be a bridge between science and the community and let my experience speak.

Q: What is making your job hard?

Fitzpatrick: Anything that’s wild and crazy spreads like wildfire. Credible messengers have to be part of the solution. When the lockdown first happened, people were texting me, calling me, sending me emails: Is this really true? Can you read this for me? Should I believe this? And I thought, I need to spring into action.

Q: What gives you hope?

Fitzpatrick: I’m never without hope. Because this too shall pass. A lot of damage is being done right now, but I don’t know that it’s irreparable. Black people have survived slavery; American Indians have survived the genocide. We just have to figure out how to become more resilient and deal with it.

Evan J. Anderson is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta, which has been conducting trials of Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine and others. He supports testing promising vaccine candidates in children.

Q: Tell us about your experience.

Anderson: (Long pause) This has been a very challenging experience, having watched patients die with no therapeutic options. Now we have some major advances as far as helping to improve care. Patients are doing better than they did early in the pandemic and that’s been great.

Q: What have you learned during the pandemic?

Anderson: That a focused approach by industry, academics and the government can result in dramatic improvements in being able to move vaccines forward from the laboratory into early phase and now late-phase clinical trials, shortening the timelines for conducting those studies and for getting data out and available to the public.

Q: What has surprised you about the public’s response to the pandemic?

Anderson: The anti-science bent of segments of the population, and the antagonism toward basic public health interventions for decreasing SARS CoV-2 transmission. Plus the polls that indicate that a substantial percentage of the population will categorically refuse COVID-19 vaccines. That’s surprising. And discouraging, honestly.

Q: What is making your job hard?

Anderson: Just the cumulative exhaustion. We ramped up the beginning of March to sprint pace, and now I’ve been going at that pace for [many] months. At a certain point, you just can’t keep sprinting any longer.

Q: What gives you hope for the future?

Anderson: The high vaccine efficacy observed in the Moderna and Pfizer trials is really encouraging. If these vaccines (and potentially others as well) can be quickly distributed and people receive a highly effective vaccine, we will likely be seeing a return to a “new normal” sometime in 2021. To accomplish this, we still have much work to do, including evaluating these vaccines in pregnant women and children. There is much hope for better days ahead.

Virologist Angela Rasmussen of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, is living in Seattle while doing research on SARS CoV-2. Trying to combat misinformation has become a big part of her job.

Q: What do you want people to know about your experience?

Rasmussen: It’s been just as grueling for scientists as it has been for everybody else. It’s been incredibly frustrating and demoralizing to see expert advice — from epidemiologists, from physicians, from virologists like me — be ignored.

Q: What have you learned during the pandemic?

Rasmussen: How one very small virus that we didn’t even know about until December 30 last year — and actually, didn’t know was a coronavirus until January 10 this year — could profoundly affect the entire human species.

Q: What is making your job hard?

Rasmussen: The misinformation. It makes it 10 times harder for me to do my job if every time I write a paper, every time I write a perspective piece, every time I even tweet something, I have to think very carefully about what I say. Because it could be taken out of context and people could run with it in ways that are really harmful.

Q: What gives you hope for the future?

Rasmussen: Those of us who work with emerging viruses — we all know each other. This has given me opportunities to meet people who are approaching some of the same problems, but from a very different professional perspective. And that has been really wonderful. Hopefully it’s going to lead to some great research.

Q: What do you miss about your old life?

Rasmussen: I miss being able to think of my job as a job, and not as: What sort of crushing despair do I have to deal with today?

Thomas Quade is health commissioner of Geauga County, Ohio, managing a team of about two dozen people who enforce state law to protect public health.

Q: How has the pandemic changed your work?

Quade: Some of the work that we would normally do got put on hold. We didn’t start off the year with a lot of extra contact tracers and epidemiologists, for example, so we retrained our sanitarians, who normally inspect restaurants, to make COVID contact-tracing calls.

Q: What do you want people to know about your experience?

Quade: Folks at local health departments — and this is not just mine, this is across the country — are working harder than they’ve ever worked. And they weren’t slacking before. Public health in this country has been lean for the last 15 years; in the 2008 recession we lost about 25 percent of the U.S. public health workforce and it has not been replenished.

Q: What have you learned during the pandemic?

Quade: It reinforced that we really have to have relationships in the community. The United Way or YMCA, or your church or your school, can say the same things we would say, but it’s absorbed differently. We need those partners, otherwise the story is no longer about fighting the virus. The story is about fighting the people that are fighting the virus. And that’s not productive.

Q: What has surprised you about the public’s response?

Quade: That we’re getting pushback on what are very simple strategies. These are things that parents tell little kids: wash your hands, stay home when you’re sick. What surprised me is how successfully this has been made political, that a mask says you’re for something or against something.

Q: What gives you hope for the future?

Quade: (Long pause) What gives me hope is that, as tired and worn out as my colleagues are — not just here at this health department, but my national network of public health colleagues — they seem to have reserves of energy left. I think it’s because diehard public health professionals are mission-oriented. If it was just a job, none of us would be doing this.