The proliferation of face coverings to keep COVID-19 in check isn’t keeping kids from understanding facial expressions, according to a new study by University of Wisconsin-Madison psychologists.

Category: Uncategorized

Christmas trees can be green because of a photosynthetic short-cut

How can conifers that are used for example as Christmas trees keep their green needles over the boreal winter when most trees shed their leaves?

How can conifers that are used for example as Christmas trees keep their green needles over the boreal winter when most trees shed their leaves?

Research reveals compromised transfer of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies through placenta

Recent analyses indicate that pregnant women and newborns may face elevated risks of developing more severe cases of COVID-19 following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Stupid Strong Charitable Foundation Pledges $250,000 to Support Gastric Cancer Research at MD Anderson Cancer Center

Stupid Strong Charitable Foundation is proud to contribute $250,000 to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center to support cutting-edge research in gastric cancer led by Jaffer Ajani, M.D., professor of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology.

Immersive virtual reality boosts the effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation for chronic pain

For patients receiving spinal cord stimulation (SCS) for chronic pain, integration with an immersive virtual reality (VR) system – allowing patients to see as well as feel the effects of electrical stimulation on a virtual image of their own body – can enhance the pain-relieving effectiveness of SCS, reports a study in PAIN(r), the official publication of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

These science claims from 2020 could be big news if confirmed

Discoveries about the cosmos and ancient life on Earth tantalized scientists and the public in 2020. But these big claims require more evidence before they can earn a spot in science textbooks.

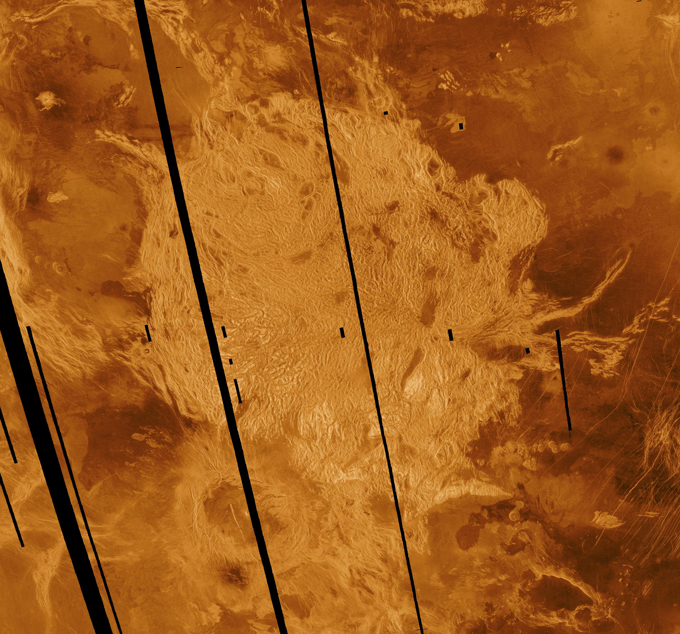

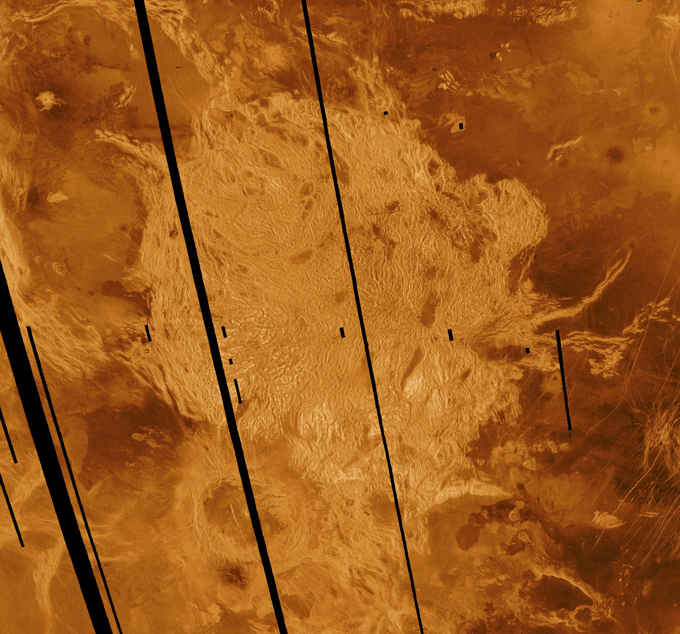

Cloudy with a chance of life

The scorching hellscape next door may be a place to look for life. Telescopes trained on Venus’ clouds spotted traces of phosphine in quantities that suggest something must be actively producing the gas (SN: 9/14/20). On Earth, phosphine is emitted by certain bacteria or industrial processes, leading some astrobiologists to speculate that microbes may be living in Venus’ relatively temperate upper atmosphere. But other research teams’ analyses suggest the phosphine detection was a misread — perhaps the result of a fluke in data processing (SN: 10/28/20).

Flashback

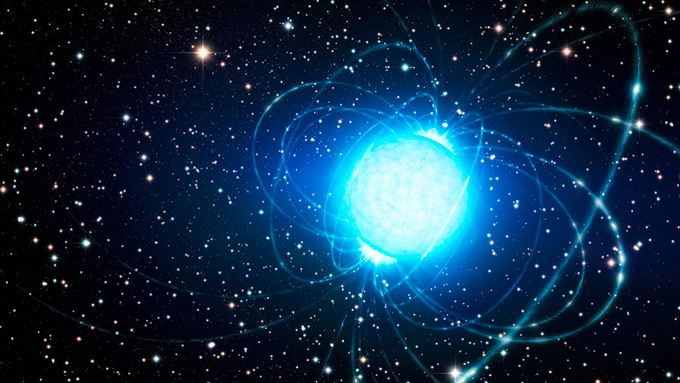

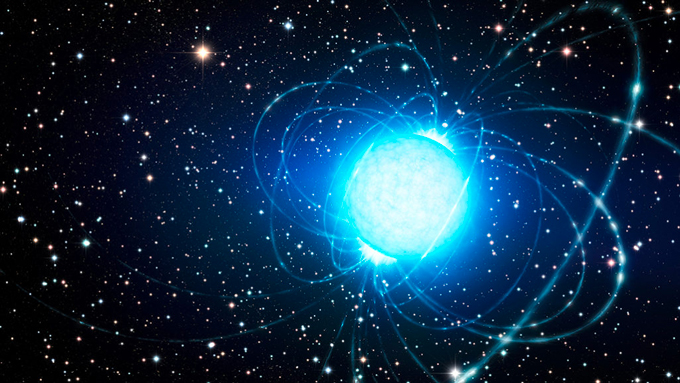

For the first time, astronomers may have glimpsed a fast radio burst in the Milky Way. Even more intriguing, the source of the super-bright boost of radio waves appears to be a magnetar — a type of neutron star with an intense magnetic field (SN: 6/4/20). But it’s too soon to claim that magnetars caused any of the dozens of previously detected fast radio bursts, as those flashes came from galaxies too far away to trace the bursts back to a source.

Totally tubular

Tubes stuck to the outer shells of hundreds of fossilized brachiopods discovered in an outcropping in China may have housed the earliest-known parasites. The clamlike brachiopods lived about 512 million years ago. Researchers speculate that organisms living inside the tubes swiped food from their filter-feeding hosts (SN: 6/2/20). That the tubes were never found alone or on other fossils in the outcropping suggests that the organisms could not survive on their own. But some critics question whether the relationship was truly parasitic, given that the tubed-up brachiopods didn’t seem any worse off than their tube-free counterparts.

Found: ordinary matter

Only about half of the universe’s expected amount of ordinary matter has ever been cataloged. But this year, astronomers claimed that the other half is hiding out in intergalactic space (SN: 5/27/20). That conclusion is based on an analysis of how a small sample of fast radio bursts from other galaxies were distorted by particles on the way to Earth. Before the case of the missing matter can be closed, though, more of these bright blasts of radio waves need to be examined.

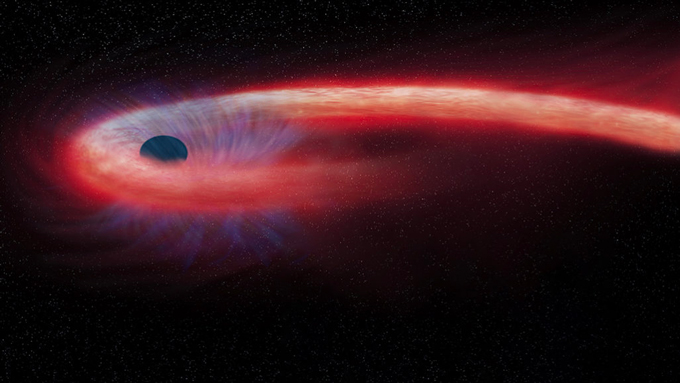

Start your cosmic engines

A ghostly subatomic particle may have been revved up by a star’s destructive encounter with a black hole. Sensed by the IceCube detector in Antarctica, the neutrino carried 200 trillion electron volts — about 30 times as much energy as that of a proton accelerated by the Large Hadron Collider. Scientists matched the neutrino detection to a flash of light in the sky caused by a black hole shredding a star. The probability of the neutrino and the flash coinciding by chance is just 0.2 percent. If the finding holds up, it would be only the second time a high-energy neutrino has been traced to its source, and the first direct evidence that shredding a star can accelerate neutrinos to high energies (SN: 5/26/20).

On the move

The long-running debate over when humans first traveled to and from the Americas rages on. One group of researchers reported that people arrived to North America more than 15,000 years earlier than generally thought, based on the discovery of roughly 33,000-year-old stone tools unearthed in Mexico (SN: 7/22/20). Some archaeologists, however, doubt that the artifacts are even stone tools and say they instead are just naturally broken rocks.

Another research group reported that Indigenous South Americans crossed thousands of kilometers of open ocean and reached eastern Polynesia more than 800 years ago, not long after settlers from Asia initially colonized the islands (SN: 7/8/20). That conclusion rests on genetic evidence suggesting the intrepid South Americans mated with ancient Polynesians. But some anthropologists question whether early South American groups had the equipment or seafaring skills necessary for the journey. Ancient Polynesians, who were expert navigators, may have traveled to South America, bringing new DNA with them on a return trip home.

How future spacecraft might handle tricky landings on Venus or Europa

The best way to know a world is to touch it. Scientists have observed the planets and moons in our solar system for centuries, and have flown spacecraft past the orbs for decades. But to really understand these worlds, researchers need to get their hands dirty — or at least a spacecraft’s landing pads.

Since the dawn of the space age, Mars and the moon have gotten almost all the lander love. Only a handful of spacecraft have landed on Venus, our other nearest neighbor world, and none have touched down on Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter thought to be one of the best places in the solar system to look for present-day life (SN: 5/2/14).

Researchers are working to change that. In several talks at the virtual American Geophysical Union meeting that ran from December 1 to December 17, planetary scientists and engineers discussed new tricks that hypothetical future spacecraft may need to land on unfamiliar terrain on Venus and Europa. The missions are still in a design phase and are not on NASA’s launch schedule, but scientists want to be prepared.

Navigating a Venusian gauntlet

Venus is a notoriously difficult world to visit (SN: 2/13/18). Its searing temperatures and crushing atmospheric pressure have destroyed every spacecraft lucky enough to reach the surface within about two hours of arrival. The last landing was over 30 years ago, despite increasing confidence among planetary scientists that Venus’ surface was once habitable (SN: 8/26/16). That possibility of past, and perhaps current, life on Venus is one reason scientists are anxious to get back (SN: 10/28/20).

In one of the proposed plans discussed at the AGU meeting, scientists have ridged, folded mountainous terrain on Venus called tessera in their sights. “Safely landing in tessera terrain is absolutely necessary to satisfy our science objectives,” said planetary scientist Joshua Knicely of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in a talk recorded for the meeting. “We have to do it.”

Knicely is part of a study led by geologist Martha Gilmore of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn., to design a hypothetical mission to Venus that could launch in the 2030s. The mission would include three orbiters, an aerobot to float in the clouds and a lander that could drill and analyze samples of tessera rocks. This terrain is thought to have formed where edges of continents slid over and under each other long ago, bringing new rock up to the surface in what might have been some version of plate tectonics. On Earth, this sort of resurfacing may have been important in making the planet hospitable to life (SN: 4/22/20).

But landing in these areas on Venus could be especially difficult. Unfortunately, the best maps of the planet — from NASA’s Magellan orbiter in the 1990s — can’t tell engineers how steep the slopes are in tessera terrain. Those maps suggest that most are less than 30 degrees, which the lander could handle with four telescoping legs. But some could be up to 60 degrees, leaving the spacecraft vulnerable to toppling over.

“We have a very poor understanding of what the surface is like,” Gilmore said in a talk recorded for the meeting. “What’s the boulder size? What’s the rock size distribution? Is it fluffy?”

So the lander will need some kind of intelligent navigation system to pick out the best places to land and steer there. But that need for steering brings up another problem: Unlike landers on Mars, a Venus lander can’t use small rocket engines to slow down as it descends.

The shape of a rocket is tailored to the density of air that it will push against. That’s why rockets that launch spacecraft from Earth have two sections: one for Earth’s atmosphere and one for the near-vacuum of space. Venus’ atmosphere changes density and pressure so quickly between space and the planet’s surface that “dropping a kilometer would go from the rocket working perfectly, to it’s going to misfire and possibly blow itself apart,” Knicely says.

Instead of rockets, the proposed lander would use fans to push itself around, almost like a submarine, turning the disadvantage of the dense atmosphere into an advantage.

The planet’s atmosphere also presents the biggest challenge of all: seeing the ground. Venus’ dense atmosphere scatters light more than Earth’s or Mars’ does, blurring the view of the surface until the last few kilometers of descent.

Worse, the scattered light makes it seem like illumination is coming from all directions at once, like shining a flashlight into fog. There are no shadows to help show steep slopes or reveal big boulders that the lander could crash into. That’s a major issue, according to Knicely, because all of the existing navigation software assumes that light comes from just one direction.

“If we can’t see the ground, we can’t find out where the safe stuff is,” Knicely says. “And we also can’t find out where the science is.” While proposed solutions to the other challenges of landing on Venus are close to doable, he says, this one remains the biggest hurdle.

Sticking the landing on Europa

Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, on the other hand, has no air to blur the surface or break rockets. A hypothetical future Europa lander, also discussed at the AGU meeting, would be able to use the “sky crane” technique (SN: 8/6/12). That method, in which a platform hovers above the surface using rockets and drops a spacecraft to the ground, was used to land the Curiosity rover on Mars in 2012 and will be used for the Perseverance lander in February 2021.

“The engineers are very excited about not having to deal with an atmosphere on the way down,” said spacecraft engineer Jo Pitesky of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., in a recorded talk for the meeting.

Still, there’s a lot that scientists don’t know about Europa’s surface, which could have implications for any lander that touches down, said planetary scientist Marissa Cameron of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in another talk.

The best views of the moon’s landscape are from the Galileo orbiter in the 1990s, and the smallest features it could see were half a kilometer across. Some scientists have suggested that Europa could sport jagged ice spikes called penitentes, similar to ice features in the Chilean Andes Mountains that are named for their resemblance to hooded monks with bowed heads — although more recent work shows Europa’s lack of atmosphere should keep penitentes from forming.

Another mission, the Europa Clipper, that’s already underway will take higher-resolution images when the orbiter visits the Jovian moon later this decade, which should help clarify the issue.

In the meantime, scientists and engineers are running elaborate dress rehearsals for a Europa landing, from simulating ices with different chemical compositions in vacuum chambers to dropping a dummy lander named Olaf from a crane to see how it holds up.

“We have a requirement that says the terrain can have any configuration — jagged, potholes, you name it — and we have to be able to conform to that surface and be stable at it,” says John Gallon, an engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. (The dummy lander was named for his 4-year-old daughter’s favorite character in the movie Frozen.)

Over the last two years, Gallon and colleagues have tested different lander feet, legs and configurations in a lab by suspending the lander from the ceiling like a marionette. That suspension helps simulate Europa’s gravity, which is one-seventh that of Earth’s.

Without much gravity, a massive lander could easily bounce around and damage itself when trying to land. “You’re not going to stick the landing like a gymnast coming off the bars,” Gallon says. His team has tried sticky feet, bowl-shaped feet, springs that compress and push into the surface and legs that lock to help the lander stay put on various terrains. The lander might crouch like a frog or stand stiff like a table, depending on what type of surface it lands on.

Although Olaf is hard at work helping scientists figure out what it will take to build a successful Europa lander, the mission itself, like its Venusian counterpart, remains only on some planetary scientists’ wish lists for now. Meanwhile, other researchers dream about voyages to entirely different worlds, including Saturn’s geyser moon Enceladus.

“Some people will pick favorites,” Cameron says. “I just want to land someplace we’ve never been to that’s not Mars. I’d love that.”

The new U.K. coronavirus variant is concerning. But don’t freak out

Coronavirus infections in part of the United Kingdom have rapidly taken center stage in the COVID-19 pandemic after researchers identified a variant of the virus that may be behind a recent spike in cases there.

On December 14, U.K. Health Secretary Matt Hancock first announced that the variant, called B.1.1.7., might be linked to faster spread that officials were seeing among people. In the days since, evidence supporting that hypothesis has emerged, prompting officials to put stricter public health measures in place to curb new infections — including restricting gatherings of people who don’t live in the same household.

The early evidence has prompted experts to closely monitor the new variant’s spread, but they say, there’s no cause for alarm as of now. Here are a few things to know about B.1.1.7.

It’s common for new variants of viruses to appear.

Variants of viruses, including the novel coronavirus, are always popping up. As viruses replicate in cells and make error-prone copies of their genetic blueprints, the viruses naturally accumulate mutations (SN: 5/26/20).

Some rare mutations do change how a virus behaves, but most don’t. Instead, researchers primarily use variants as “fingerprints” to track disease spread, says Stephen Goldstein, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The new U.K. variant seems to spread rapidly, but scientists don’t know for sure.

The U.K. variant does have more changes compared with its closest relative than most other coronavirus variants. “Nothing of what I’ve seen … is the single definitive, killer piece of evidence that this is definitely more transmissible,” says Aris Katzourakis, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Oxford. “But there is so much circumstantial stuff all pointing in that direction.”

For example, people who are infected with B.1.1.7 tend to pass the virus on to more people on average and have higher amounts of the coronavirus’s genetic material in the body than people with other variants of the virus, according a Dec. 18 meeting summary from the U.K. New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. Such evidence is, as Katzourakis says, circumstantial. To know for sure, researchers need additional proof from experiments done in animals or more data from people.

Studies have also shown that one of the variant’s mutations, called N501Y, might make B.1.1.7 more contagious — perhaps by helping it bind better to ACE2, a host protein that lets the virus into cells (SN: 2/3/20). It’s unclear, however, whether all the observations together stem from a more transmissible virus, which could be harder to control.

It’s also possible that the spike in coronavirus cases could be due to human behavior, Katzourakis says. “We have recently come out of a lockdown, so a lot of that increase in case numbers could be due to the relaxation of social distancing measures.” Which scenario is more plausible should become clear in about a week or longer, he says.

It’s unknown if it causes more severe or milder disease.

A mutation in B.1.1.7 leads to a shorter version of a viral protein called ORF8 than what’s seen in other variants. But it’s unclear what ORF8 does during an infection. Some modifications in ORF8 have actually been associated with less severe COVID-19 symptoms.

There’s currently no evidence to suggest the variant causes more severe disease.

There’s also no evidence that vaccines would be less effective against it.

The U.K. variant is missing two amino acids that are targets of neutralizing antibodies, immune proteins that stop the virus from making it into a host cell. That, among a slew of other mutations in the B.1.1.7’s spike protein, could help the virus hide from some immune responses, including those induced by a vaccine.

But our bodies can attack a wide variety of surfaces on the coronavirus to control the infection, Goldstein says. So, for now, immune protection from vaccines should still be effective. Vaccines may need to be updated in the future, but perhaps not for a few years.

COVID-19 vaccine developers Pfizer and Moderna are reportedly running tests to make sure their newly authorized vaccines work against the new variant (SN: 12/18/20).

Scientists don’t know where it came from.

Where the new variant arose is a mystery. In general, coronaviruses are similar to other viruses in that their genetic material rapidly accumulates errors. But they are also different in that they are among a select group that have a viral version of spell check. Such a correction system means that coronaviruses change more slowly over time than other viruses that also use RNA as their genetic blueprint, such as influenza.

B.1.1.7, on the other hand, has far more mutations that change or remove amino acids in viral proteins than experts would expect when compared with the most closely related coronavirus variant.

One possibility is that the variant came from someone who had a weak immune system, which allowed the virus to replicate for a much longer period of time than usual and gather lots of mutations, Katzourakis says. “It seems like that was a kind of leap, something that essentially gave evolution a helping hand.” Researchers have previously seen the coronavirus change after an infection in immunocompromised patients. Such cases might help the virus pick up mutations that it might not otherwise during infections in other people with stronger immune systems.

A coronavirus variant from South Africa shares some of the U.K. variant’s changes.

The United Kingdom is not the only country to report a variant with the N501Y mutation. Such a variant is also on the rise in South Africa. Both versions acquired the change independently of one another, researchers say.

The fact that coronavirus variants in different parts of the world independently evolved the same mutation suggests that it might have some beneficial effect for the virus, Goldstein says. Some variants may be successful at spreading in the population by chance alone — an infected person hopped on a plane and spread the virus after arriving at his or her destination. But in this case, the rapid spread of B.1.1.7 in the United Kingdom and of its distant relative in South Africa hints that the change might help the variants transmit, he says.

Researchers around the world should examine coronavirus genetic material from as many infected people as possible to monitor for similar variants, experts say. That would help officials pinpoint whether the new or similar variants are spreading in other countries as well.

The variant may very well be spreading in the United States, but that’s also unclear.

Some people outside the United Kingdom have been infected with the U.K. variant, including in Denmark and Australia, but there is no evidence that it is spreading broadly in those countries yet. It’s also possible that the variant is also in the United States, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in an interview with Good Morning America on December 22.

So far, efforts to monitor the genetic makeup of coronaviruses in the United States haven’t found that specific variant of the virus. But less than half a percent of cases in the United States have been analyzed, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Public health measures like masks will still prevent the variant from spreading.

Even if it becomes clear that B.1.1.7 is more contagious than other versions of the coronavirus, wearing masks and social distancing are still going to be crucial tools to curb its spread (SN: 11/11/20). Officials “may have to think about introducing additional measures, but it’ll be the same kind of measures — potentially more often and more stringent.”

For example, while there is now evidence suggesting that another coronavirus variant with a mutation, called D614G, that emerged after the pandemic began and spread around the world is more contagious than variants without the change, “it hasn’t prevented countries like Vietnam or Taiwan or South Korea or New Zealand from being able to contain the virus,” Goldstein says.

“I think it shows us that although there may be small differences in transmission efficiency, it doesn’t mean that the virus is all of a sudden uncontainable.”

Preventing Nurse Suicides as New Study Finds Shift in Method

In a new study, University of California San Diego School of Medicine and UC San Diego Health researchers report that the rate of firearm use by female nurses who die by suicide increased between 2014 to 2017. Published December 21, 2020 in the journal Nursing Forum, the study examined more than 2,000 nurse suicides that occurred in the United States from 2003 to 2017 and found a distinct shift from using pharmacological poisoning to firearms, beginning in 2014.

Research explores hallmarks of effective conversations

What makes people good at having conversations? In a recent paper, Cornell researchers explored conversations on a crisis text service in order to figure out how to answer that question.