More than a year and a half into the pandemic, researchers are beginning to get a handle on how the coronavirus makes people sick and what to do about it. That includes some valuable lessons about what doesn’t work. Now the trick is to find drugs or therapies that do work, especially for people who aren’t sick enough to go to the hospital. Early treatment may limit transmission of the virus and keep people out of overburdened hospitals.

Finding those treatments is proving to be particularly tricky. While the race to create vaccines was astonishingly successful, effective treatments have proved elusive. But they are crucial, especially because the pandemic is far from over. After seemingly gaining ground on the virus in the United States, cases and hospitalizations are again on the rise as the more infectious delta variant sweeps across the country (SN: 7/2/21). The variant is driving a surge of new infections globally, too.

“We still have a lot of people who remain unvaccinated” and at risk of getting COVID-19, says Susanna Naggie, an infectious diseases physician at Duke University School of Medicine. “The need for a safe therapy that can be administered at home remains huge.”

A few drugs — including the antiviral medication remdesivir, immune system–calming antibody therapies such as baricitinib and tocilizumab and steroids such as dexamethasone — have been literal lifesavers for some of the sickest patients (SN: 4/29/20; SN: 10/30/20; SN: 9/2/20). For instance, real-world data from more than 98,000 people hospitalized with COVID-19 suggest that infusions of remdesivir cut the chance of dying by up to 23 percent, researchers from the drug’s maker Gilead Sciences, Inc., reported at the World Microbe Forum, held online in June. Still, those drugs don’t save everyone, and they are reserved for people who are hospitalized.

Some lab-made antibodies may help newly diagnosed people avoid hospitalization and severe illness (SN: 9/22/20). But relatively few people have gotten the treatment, which requires intravenous infusions.

While finding effective, easy-to-take treatments has been no easy task, it’s not for lack of trying. But it can seem like for every encouraging lead, there’s a hurdle. Here’s a look at some of the challenges that have stymied efforts to develop treatments for COVID-19 and some of the promising approaches, including some in pill form, that may still pan out.

A false lead

To speed the search for treatments, researchers first reached for drugs already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and in the medicine cabinet for treating other diseases. Most of the proven treatments for COVID-19 started this way, with the exception of remdesivir. That antiviral drug was developed to fight RNA viruses, but hadn’t been approved prior to the pandemic. It is now the only FDA-approved treatment for COVID-19.

Most repurposed drugs haven’t panned out as coronavirus treatments despite some tantalizing hints they might. Now, scientists have insight into one reason why drugs such as hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine and about 30 others don’t work in people even though they stop SARS-CoV-2 from infecting cells in lab dishes (SN: 8/2/2020). It’s all connected to a particular side effect of the drugs.

The route to this discovery began in 2020 when researchers identified proteins called sigma receptors in human and monkey cells that interact with some of the virus’s proteins. Researchers thought that might be important for infection. So they proposed that some common antidepressants, antipsychotics and antihistamines may disrupt those interactions and might stymie the coronavirus’s ability to infect people (SN: 4/30/20).

But further investigation showed that for many of the compounds, there was no relationship between a drug’s ability to grab the sigma receptors and effectiveness against the virus when tested on cells grown in lab dishes, says medicinal chemist Brian Shoichet. The drugs either targeted the sigma receptors or they stopped the virus from growing. They didn’t do both.

“When you see something like that, it’s a real showstopper for someone like myself,” says Shoichet, of the University of California San Francisco School of Pharmacy. “It really makes you think, ‘Oh, we’re digging in the wrong place. There’s something fundamentally wrong with our hypothesis,’” he says. The evidence seems to indicate that targeting sigma receptors won’t improve COVID-19 symptoms, he says.

But of the drugs that did have potent antiviral effects, many were ones known to disrupt the way human cells build and use fats called lipids, he noticed. That disruption can lead to a potentially serious side effect called phospholipidosis. That side effect causes lipids to build up in cells, giving some cells a foamy appearance. That buildup can lead to inflammation, which can damage organs or interfere with their functions.

Shoichet and his colleagues wondered if that lipid disruption was causing the antiviral effect. Teaming with researchers from the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research in Basel, Switzerland, they first tested whether the drugs were causing the side effect in cells. Sure enough, the more phospholipidosis the drugs caused, the more potently they inhibited virus growth in those cells, the researchers reported June 22 in Science.

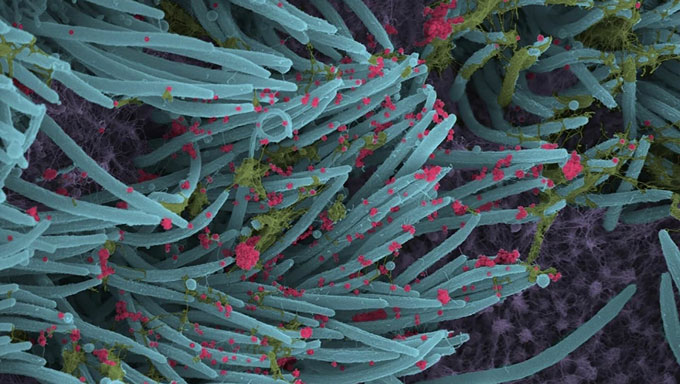

That’s because SARS-CoV-2 needs to build lipid bubbles inside cells where it can replicate. Phospholipidosis may interfere with that process, Shoichet says. That might be a useful property, except for one thing: The drugs that caused the side effect didn’t work in animal experiments. In mice, these drugs didn’t stop the coronavirus from replicating in lung cells, colleagues at the Pasteur Institute in Paris discovered.

This disconnect between a drug’s antiviral activity in lab dishes and its inability to protect animals may happen for two reasons, says François Pognan, an investigative toxicologist at Novartis. Either the drugs have to be given in very high doses to cause phospholipidosis — much higher than would be safe — or they need to build up over time. In lab dishes, “it’s a piece of cake,” Pognan says. But in the body, it’s very difficult to reach levels of the drug that would cause enough lipid disruption to be protective.

That finding could help researchers avoid dead-ends. If a drug stops the coronavirus from growing in cells in the lab, researchers should test for phospholipidosis. If the drug causes that side effect, it should be discarded as a COVID-19 therapy.

Following that advice could impact many ongoing clinical trials and save time and money. Currently, at least 33 drugs, including the antibiotic azithromycin, that cause phospholipidosis are being tested in 136 clinical trials.

One trial at the University of California, San Francisco tested whether azithromycin could clear up symptoms of COVID-19 in 263 newly diagnosed people. There was no difference between the drug and a placebo, researchers reported July 16 in JAMA. What’s more, people taking the antibiotic were much more likely than those getting a placebo to report side effects, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea and nausea. And five people taking azithromycin were hospitalized, while no one in the placebo group was. An independent monitoring committee recommended ending the trial for “futility.”

Another 180 trials were devoted to hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, which also lead to the lipid foaming side effect. (Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine have other issues, too: Both fail to block the coronavirus’s preferred route of entry and don’t help patients, researchers discovered last year (SN: 8/2/20).)

Together, those 316 trials cost an estimated $6 billion. That money, time and effort would be better spent on drug candidates that don’t cause the side effect, Shoichet, Pognan and colleagues say.

Helping too few

Even drugs that work as they are supposed to might not be worth giving to everyone who gets COVID-19. Take interferons. These immune system chemicals are among the first to do battle with viruses (SN: 8/6/20). Before the pandemic, researchers at the drug company Synairgen, a spinoff company from the University of Southampton in England, developed an inhaled form of interferon beta and were testing it in people with other respiratory problems, including MERS coronavirus infections. The company quickly began clinical trials to see if interferon beta could help COVID-19 patients, too.

In a trial in 101 hospitalized patients and 120 people who were ill but still at home, participants were randomly assigned to get either inhaled interferon or a placebo. Only two people in the home-care group needed hospitalization, the company said in a preliminary report. Both were in the placebo group. That’s a low percentage of people — about 3 percent — much lower than researchers expected, says Richard Marsden, Synairgen’s CEO. That’s too few to figure out how to target the drug to those who might benefit the most.

The vast majority of people, even people who have health conditions that put them at high risk of complications, don’t get sick enough to need hospitalization. “They have very mild symptoms,” Marsden says. “They need little more than [acetaminophen], a hot water bottle and some sympathy, and they recover very well.”

About 10 percent of people will develop concerning breathlessness and some may end up in the hospital. But it’s so relatively few that you would need to treat a huge number of people just to stop one or two from landing in the hospital, Marsden says. “That’s the quirk of this virus,” he says.

For viruses such as the original SARS or the MERS coronaviruses, which have much higher mortality rates, it makes sense to treat everyone who gets sick right away. But with SARS-CoV-2, the severe breathlessness that sends people to the hospital usually doesn’t show up until the second week of infection. That may be how long it takes for the virus to move down into the lungs and start causing damage there that interferon beta may be able to counter, Marsden hypothesizes (SN: 7/22/2021). So treating people at home earlier might not help anyway.

Results of a Phase III trial for efficacy of interferon beta for hospitalized patients are expected later this year. In the earlier trial, hospitalized people who got the drug were more than twice as likely as those that got a placebo to recover fully to a point where they had no restrictions on their activities, the company reported.

“It’s not worth giving our drug to everybody. Wait until they develop lower respiratory tract illness and then give it to them,” when it may do more good, Marsden says. “It’s a huge ask of a drug that it be so safe and so efficacious that you can give it to everybody.”

Trial troubles

Keeping people out of the hospital in the first place would help relieve the burden on health systems and perhaps prevent people from developing long-term consequences from severe illness. But it’s no surprise that early in the pandemic researchers weren’t focused on at-home treatments.

“A lot of the scientific community was just trying to save lives, particularly for patients who were in the hospital,” says Esther Krofah, executive director of FasterCures, part of the Milken Institute think tank based in Washington, D.C. “But there was not a full concerted effort on repurposed drugs that could be helpful for mild to moderate cases.”

One reason for that is that hospitalized patients are easier to recruit into studies, says Naggie of the Duke Clinical Research Institute. “You don’t have to convince them to come in and communicate with the team.”

Outpatient studies often have to advertise, set up hotlines, send letters or call people on the phone to find volunteers willing to take part in the trial. And that can set up situations in which multiple trials are competing for participants. As a result, many trials conducted over the past year didn’t enroll enough people to get definitive answers about whether their treatments worked.

“We need to create a much more cohesive clinical trial system in this country,” Krofah says.

That’s beginning to happen. The National Institutes of Health have launched a large trial called ACTIV-6, expected to enroll 13,500 people. It is similar to earlier trials of hospitalized patients that determined that remdesivir, steroids and other treatments can reduce death rates or shave days off hospital stays.

ACTIV-6 will test a battery of existing drugs against a placebo to see if any of them can reduce the chance of people needing hospitalization. The goal is to have five or six, and potentially up to eight “arms” of the trial with all of the drugs being tested at the same time, each in about 600 people, says Naggie, who is one of the study’s principal investigators. People getting the placebo will serve as the comparison group for all of the drugs. First up is the antiparasitic drug ivermectin.

Ivermectin has been used globally for a long time in various forms for treating intestinal parasitic worms, head lice and skin conditions such as rosacea. It’s given to animals to prevent heartworm disease and to treat infections with other parasites. Generally, it is a safe drug, Naggie says.

And there are hints it could work against SARS-CoV-2. The drug had already been shown to limit infections caused by HIV and other RNA viruses, including West Nile, dengue and influenza viruses in lab studies. Researchers in Australia tested ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2 in green monkey cells growing in lab dishes and found that the drug could quickly shut down production of viral RNA, the group reported last year in Antiviral Research.

Clinical trials have pitted ivermectin against COVID-19. But the studies measured success by different standards, with some tracking viral loads or symptom severity, and others tracking time to recovery or death. Some were randomized and placebo-controlled; others didn’t have control groups. Some trials were done in hospitalized people, others in outpatient settings. Some mixed ivermectin with other drugs.

The results varied. Some showed a benefit of the drug; others showed no difference between ivermectin and a placebo or standard care. Those trials did have one thing in common, says Naggie. “None of them are yet definitive. The quality is not as high as we would like it to be.”

To date, health officials have recommended against taking ivermectin for COVID-19 outside of clinical trials. Even the pharmaceutical company Merck, which makes ivermectin, has said there is no evidence to support the drug as a COVID-19 treatment.

“What that means is please don’t go take your dog’s ivermectin or your horse’s ivermectin. It has not been proven to be an effective remedy for COVID-19,” Naggie says.

Her study will test ivermectin’s effect in people 30 and older who have been sick for 10 days or less. And people don’t have to leave their homes to participate. Study participants will be mailed the pills and will be asked to fill out daily surveys about their symptoms. Perhaps the trial will show once and for all whether ivermectin works as well in people as it does in lab dishes.

A quick-fix pill?

Meanwhile, other treatment trials are already well under way, some of which may announce results before the end of this year. Of particular interest are orally administered drugs, some of which are “looming on the horizon quite quickly,” says Yasmeen Long, director of FasterCures.

Among the most promising is an antiviral drug called molnupiravir (formerly EIDD-2801), The drug mimics a building block of RNA and interferes with the virus’s replication, much like remdesivir does (SN: 8/24/2020). Unlike remdesivir, the new drug is in pill form and can be easily be given to newly diagnosed people.

Merck and Miami-based Ridgeback Biotherapeutics are testing the antiviral in a Phase III trial, which will measure the drug’s efficacy in non-hospitalized people who have at least one risk factor for serious complications from COVID-19. Already the U.S. government has agreed to buy 1.7 million courses of the drug, if the FDA grants it emergency use authorization, Merck announced in a news release.

Early results of a Phase II trial of safety, dosing and efficacy found that people who took 800 milligrams of molnupiravir twice daily for five days had less virus in their noses than people who got a placebo, researchers reported June 17 at medRxiv.org. Within three days of starting treatment, only 1.9 percent of the 202 people taking 800 mg of molnupiravir had detectable virus in nasal swabs. That compares with 16.7 percent of those taking the placebo.

By day five of treatment, researchers detected no virus in people taking molnupiravir, while 11.1 percent of people on the placebo still had detectable virus in their swabs. If those preliminary results, which have not been reviewed by other scientists yet, hold up, it may mean that the drug could shorten the course of illness, keep people out of the hospital and reduce the chance of spreading the virus to others.

Other studies, including one testing the antidepressant pill fluvoxamine (SN: 2/1/21) and a large study of other repurposed drugs may also yield easy, early and effective treatments. “Which is great,” Naggie says, because “whether or not one trial is going to change all of clinical practice is questionable.” Having multiple studies of people who are sick at home might “help move the needle on what might be useful,” she says.