Chapter 9:

Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA

Alex M.

When I was a small boy the neighborhood kids would gather on weekends to play kickball. We would all line up eagerly waiting to hear our name called for each team. I would look down at the ground and shuffle my feet knowing once again my name would the last one spoken. That was the start of a lifetime of not fitting in.

Raised as an only child in Kentucky during the 1950s, my father worked as a chemical engineer while my mother spoiled me at home. Food, clothing and shelter were easily provided. Our neighborhood was safe enough to leave our doors unlocked. Stay at home moms watched over each other’s kids so we never got into too much trouble. On Halloween we roamed far and wide, filling our sacks till they overflowed. At Christmas entire families went caroling house to house.

The only advice I remember getting from my father was to work hard, never ask for anything from anybody, get the best education I could and find a good job. My mother taught me that it didn’t matter who I thought I was or what I felt; all that mattered was how I appeared to the world. Keep your mouth shut, control your emotions, trust no one, and hold your secrets close. Lying to myself and pretending with others became routine.

When my father drank he turned into an angry, combative alcoholic who terrified me and abused my mother. As his life became more unmanageable our lives became more unmanageable.

I lived in fear of my father’s rages and not knowing when my mother would grab me up to flee the house during yet another domestic quarrel. All I wanted was to escape the chaos. At an early age I discovered books. I would hide in my room and read. Reading took me to a safe place, but it was empty and lonely.

Down deep I yearned to be part of something more. A lot more. Like Bill W., I wanted to prove to the world I was important. I wanted to fit in with others, be accepted and be the big-shot. I wanted the world to do my bidding and when it didn’t I got angry. The first resentment I remember was when the bully next door hit me with a sucker punch when I was five. l got even and remember his name to this day.

A doctoral dissertation – “Experiences of Atheists and Agnostics in AA” – is based on the book Do Tell. For more information click on the above image.

Going through school I tried to fit in with various groups. There were the usual Nerds, Jocks, Scholars and Romeos. None welcomed me. After a while I found a few outcasts who spent their time drinking. An unpopular group, they stayed in the shadows. Since I had recently discovered bourbon would help me sleep at night and ease my worries during the day, I joined the group. In no time those misfits became my friends and I worked to become the best drinker around. At last I fit in.

In high school I developed an interest in Medicine and I decided I was going to become a doctor. I knew it would take many years of schooling and hard work but I felt it was a worthy goal and might even relieve some of the turmoil in my life.

Somehow I was able to balance drinking and schooling long enough to enter a fine college in Philadelphia where I was on my own for the first time. Recurrent blackouts that started during freshman year terrified me, but instead of addressing the cause I denied there was a problem.

As my college drinking progressed my grades worsened but my desire to become a physician overcame my desire to drink. As a hard drinker, I was able to cut down on the alcohol and graduated with honors.

During medical school and later training I continued to drink when off duty but was too busy to drink while working. Once in medical practice, like Dr. Bob, I felt an obligation never to drink while working with patients but drank to oblivion when not at work.

During my early professional years I got married and later divorced. When I asked my wife why she wanted a divorce she said it was because I was never there for her. She was right. All I did was work and get drunk. It was all about me.

Several years after my divorce I met and married an exceptional lady from my hometown. Shortly after our honeymoon she was diagnosed with cancer and died within a few months.

The night she died I went outdoors and noticed that three white jet contrails had formed a perfect triangle in the sky. For some reason that image reminded me of the Holy Trinity. Believing God was mocking the death of my wife, I ran around screaming and cursing at the sky. I never set foot in a church again.

From that point on I used my wife’s death as justification to become even more selfish and self-centered. I drank with impunity. I just didn’t care anymore. I left practice and took a medical administrative position. Somehow I managed to remain employed but my drinking progressed over the next ten years. I drifted from desk job to desk job where it was easier for me to drink without consequence. By the time I reached my early fifties I owned my own medical consulting business which allowed me to drink however I wanted.

Through those years I had acquired a third wife who no longer wanted to be around me and a family that I had pushed aside. Eventually I stopped working completely because work continued to interfere with my drinking. The more I drank the worse I felt. I saw no way out of my inability to live sober or my disgust at living drunk. Suicide beckoned, and I would line up shotgun shells on the table by my bed praying to have the courage to load the gun and use it. By then my life consisted of sitting on a couch yelling at nameless newscasters on TV while drinking from blackout to blackout.

One day a friend offered to take me to an AA meeting and I agreed, probably because I was still drunk. All I remember from that meeting was that folks told me to ask God for help not drinking one day at a time and to keep coming back.

Working with my sponsor, I had no problem accepting that I was an alcoholic, but I had a big problem with the default AA solution: God. Despite being raised in the church, I never felt a personal connection to any God or religion that crossed my path. No Higher Power ever manipulated my life. There was no heaven or hell. Death was final. Events were governed by the laws of nature and coincidences were not arranged by God. Even when in the depths of my pain I had never cried out “God help me”. I had no idea if there was or was not a God, and really didn’t care. I was an agnostic for sure and probably an atheist at heart.

I had repeatedly demonstrated that my own will-power and self-reliance could not get me sober, and I needed to find something to get and stay sober. Lack of power over alcohol, that was my dilemma.

Then I discovered what became for me the five most important words in AA as we know it today – “God as we understood him”. The words “as we understood him” were added to the Steps as a result of the work of Jim B., one of the very first atheists in AA. And those few words saved my life because they allowed me to turn to a spiritual power of my own understanding for help. I no longer had to rely on a religious power of someone else’s understanding.

Then I discovered what became for me the five most important words in AA as we know it today – “God as we understood him”. The words “as we understood him” were added to the Steps as a result of the work of Jim B., one of the very first atheists in AA. And those few words saved my life because they allowed me to turn to a spiritual power of my own understanding for help. I no longer had to rely on a religious power of someone else’s understanding.

In “Working With Others” Bill says, “If the man be agnostic or atheist, make it emphatic that he does not have to agree with your conception of God. He can choose any conception he likes, provided it makes sense to him. The main thing is that he be willing to believe in a power greater than himself and that he live by spiritual principles”. (BB, p. 93)

My responsibility today is to carry the message of hope and recovery to another alcoholic who still suffers. To be effective I must put aside my personal frustration that the Big Book not to subtly preaches that the highest Higher Power available to alcoholics is the traditional Christian God. This is not really surprising, given the influence of the Protestant Oxford Group in the early growth of AA.

So I got out pen and paper and wrote down what the “God of my understanding” looked like. In no way did it resemble the God of my upbringing, but it was a power that I could turn to for strength, direction, and guidance as I went through each day trying to do the next right thing.

But what could I to replace God with? Would it be Willingness, or Honesty, or Open-Mindedness, or Group of Drunks, or Homegroup, or Sponsor, or Allah, or Confucius, or Buddha, or Great Spirit, or the Cosmos, or Nature, or Love, or Compassion, or Tolerance or Service?

I needed some kind of power in my life by which I could not only stay sober but also find a new way of living. I couldn’t rely entirely on the power of my own self-will or self-reliance, since that approach had failed completely. So I had to find some other power of my understanding by which I could live. That power was to be mine, and mine alone. No longer need I feel intimidated by anyone else’s Higher Power that was discussed in the rooms of AA.

The power I draw on today comes from the feeling I get deep within me when I look up at the stars and realize that somehow all of us in this universe are connected. I am not connected by choice or by some imaginary divine hand. I am connected by the collective power of Love, Goodness and Compassion. In AA terms these spiritual principles are “the God of my understanding”.

My power is not a heavenly power; it is a human power. It is not a power created by my self-will; it simply exists because I exist. This is the power I turn to for strength, hope and direction in my life, rather than the power of John Barleycorn.

I feel my power most when I am in the rooms of AA and working one-on-one with other alcoholics. I especially like working with alcoholics struggling with the “God thing”, since I can share my story and be living proof that any of us can get sober, including those who struggle with their own concept of religion, God, Higher Power or spirituality.

Today I am grateful that Bill W. created AA, but I am so much more grateful for his fellow alcoholics Jim B., Hank P. and others who ensured AA could provide for not only for believers, but also for non-believers like myself. Certainly, more needs to be done to further “widen the gateway” of our fellowship, but that’s a story for another day.

![Do Tell! [Front Cover]](https://nrdblogs.nationalrehabdirectory.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Do-Tell-Full-Blue-Front-Cover-200-FRAMED.jpg) This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

The paperback version of Do Tell! is available at Amazon. It is also available via Amazon in Canada and the United Kingdom.

It can be purchased online in all eBook formats, including Kindle, Kobo and Nook and as an iBook for Macs and iPads.

The post A Friend of Jim B. first appeared on AA Agnostica.

Then I discovered what became for me the five most important words in AA as we know it today – “God as we understood him”. The words “as we understood him” were added to the Steps as a result of the work of Jim B., one of the very first atheists in AA. And those few words saved my life because they allowed me to turn to a spiritual power of my own understanding for help. I no longer had to rely on a religious power of someone else’s understanding.

Then I discovered what became for me the five most important words in AA as we know it today – “God as we understood him”. The words “as we understood him” were added to the Steps as a result of the work of Jim B., one of the very first atheists in AA. And those few words saved my life because they allowed me to turn to a spiritual power of my own understanding for help. I no longer had to rely on a religious power of someone else’s understanding.![Do Tell! [Front Cover]](https://nrdblogs.nationalrehabdirectory.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Do-Tell-Full-Blue-Front-Cover-200-FRAMED.jpg) This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

The foundational base of the AA triangle is labeled “recovery”. As a starting point, that makes complete sense to me. Without recovery from alcohol addiction, we are of little use to others in the fellowship and in our personal lives. What I would challenge however is the AA twelve step model as being a one size fits everyone stand-alone method of recovery.

The foundational base of the AA triangle is labeled “recovery”. As a starting point, that makes complete sense to me. Without recovery from alcohol addiction, we are of little use to others in the fellowship and in our personal lives. What I would challenge however is the AA twelve step model as being a one size fits everyone stand-alone method of recovery.

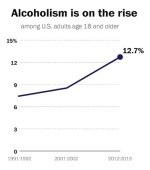

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.”

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.” Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.

Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.