A press conference on this topic will be held Tuesday, Aug. 17, at 9 a.m. Eastern time online at www.acs.org/fall2020pressconferences.

Author: bkellaway

Questions & Answers – AA Agnostica

The creator of the Polish website Agnostics and Atheists in AA recently asked me a number of questions. Here are the questions

and my answers.

By Roger C

How long have you been in AA?

I’ve been in AA since I got sober a little over a decade ago (March 8, 2010). However, after three months of attending mainstream AA meetings, I became terrified that I would start drinking again, because I couldn’t stand the meetings. All the God stuff, you know. And the meetings ending with the Lord’s Prayer. I then accidentally discovered the oldest secular AA meeting in Canada, Beyond Belief Agnostics and Freethinkers, started in Toronto, Ontario on September 24, 2009. I went to the meeting. I loved the meeting! I remember walking along Bloor Street after it was over and I threw my hands up in the air and shouted “I’m saved!”

Are you an agnostic or an atheist?

I am an agnostic. Life to me is a “Magical Mystery Tour”, as per the Beatles. I certainly don’t believe in a anthropomorphic, interventionist, male deity. Not a chance. I should also note that I have a Master’s degree in Religious Studies obtained from McGill University in Montreal, Québec.

I am an agnostic. Life to me is a “Magical Mystery Tour”, as per the Beatles. I certainly don’t believe in a anthropomorphic, interventionist, male deity. Not a chance. I should also note that I have a Master’s degree in Religious Studies obtained from McGill University in Montreal, Québec.

As an agnostic I studied and taught there for a decade, and I read the New Testament in its original language, Koine Greek. But I was always an agnostic. And everybody at McGill knew that and I was treated with great respect.

So, as an agnostic, what was I doing in the Faculty of Religious Studies? Well, one of my main reasons was to figure out why people believe in a supernatural, anthropomorphic deity. It is my understanding that it isn’t until we humans are about nine years old that we realize that our lives will end – with our death. Oh, my! So a main reason for religious belief is the denial of mortality and the invention of immortality – of course not for all other animals but just for we human animals.

Moreover and as a consequence religion is a cultural issue. As Richard Dawkins puts it in his book The God Delusion “Though the details differ across the world, no known culture lacks some version of the… anti-factual… fantasies of religion.” (p. 166). And that is passed along from one generation to another. Religion is hammered into children by their parents. It was certainly obvious that religion had been a key part of the early lives of the soon to be ordained ministers at McGill University.

Did you immediately reveal in the AA fellowship that God was not a part of your recovery?

Yes I did. And it was the huge disrespect I got at mainstream AA meetings as a result that really disturbed me, and made me want to get the hell out.

Is your home group a special group for agnostics and atheists, or is it a regular AA meeting?

I attended three secular AA meetings in Toronto – Beyond Belief Agnostic and Freethinkers, We Agnostics and We Are Not Saints – for roughly six years until I started the We Agnostics meeting in Hamilton (an hour away from Toronto) on Thursday, February 4, 2016. The meeting was a huge success and a second We Agnostics meeting on Mondays was launched on September 10, 2018. Of course since mid-March of this year both have been zoom meetings.

But now – hallelujah! – the Face to Face meetings at the First Unitarian Church are scheduled to recommence on Monday, August 24. We will, of course, play it safe. As Heather, one of the meeting organizers put it, “I think we should err on the side of extreme caution”. There will, of course, be masks, hand sanitizing, social distancing…

But f2f meetings are important, particularly for newcomers to AA.

How many agnostic AA groups are there in the area you live in?

In Hamilton there is only the one We Agnostics group, with two meetings. Toronto has some 500 AA meetings a week. Ten of the groups are secular and there is a secular AA meeting each and every day (when there is no pandemic). In all of the province of Ontario there are 20 secular AA groups and 24 meetings every week.

If an agnostic or an atheist asks you for sponsoring do you use the Big Book or do you rely on other texts?

No, I do not use the Big Book. The word “God” (or “He” or “Him” etc.) is used 281 times in the first 164 pages of the Big Book. A Christian God, by the way. The book is hugely disrespectful of non-believers and of women. I have published, via AA Agnostica, a total of eight secular AA books. One of them was written by two women back in 1991. It’s called The Alternative 12 Steps – A Secular Guide to Recovery. When I first found the book, it had been out of print for over a decade. In order to publish a second edition, I needed the permission of the authors, and it took me a year to find them. I published the second edition in 2014.

No, I do not use the Big Book. The word “God” (or “He” or “Him” etc.) is used 281 times in the first 164 pages of the Big Book. A Christian God, by the way. The book is hugely disrespectful of non-believers and of women. I have published, via AA Agnostica, a total of eight secular AA books. One of them was written by two women back in 1991. It’s called The Alternative 12 Steps – A Secular Guide to Recovery. When I first found the book, it had been out of print for over a decade. In order to publish a second edition, I needed the permission of the authors, and it took me a year to find them. I published the second edition in 2014.

Today, another one of my favorite books is Staying Sober Without God. Published in 2019, it also has a good set of 12 steps called The Practical Steps.

What was the reason you started the AA Agnostica website?

Interesting question! The website was initially called “AA Toronto Agnostics” and was launched by another fellow and me in June of 2011 when the two secular AA groups in the city, including mine, Beyond Belief Agnostics and Freethinkers, were booted out of the Greater Toronto Area Intergroup (GTAI). And why were we booted out? Well, because we used a secular version of the 12 Steps. That resulted in a war that lasted for almost six years and was resolved in January 2017, when the groups were re-admitted to the GTAI as legitimate and respected members, with their secular 12 Steps.

Anyway, after six months I changed the name of the website to AA Agnostica. While initially its sole purpose was to provide information about the times and locations of the secular AA meetings it quickly became a popular site where atheists, agnostics and freethinkers in AA could share their views. Finally, a place where they could do that! That’s the historical significance of the website. Since then over 600 articles have been posted on AA Agnostica, usually one every Sunday and sometimes on Wednesdays.

How do you get articles for the website?

There are many ways. First, there is a widget on the home page of the AA Agnostica website that invites people to write an article. Even without that, a number of people who visit AA Agnostica are motivated to write an article. And I will from time to time invite various people – because of their comments, articles they have written elsewhere, etc. – to write for AA Agnostica.

Let me also add that I avoid negative articles, in particular those whose sole purpose is to attack mainstream Alcoholics Anonymous. While there are many problems with mainstream or traditional AA – and critiques are welcome! – mere grumbling and griping is not helpful.

What is your opinion about publishing brochures for agnostics in AA?

I think brochures are a good idea. When I started the We Agnostics meeting in Hamilton I created a brochure about the meeting and I brought it to every mainstream AA meeting – usually about a half hour before the meeting started – and asked them to put copies on their literature table. Some of them did and some of them threw the brochures out. But it was very helpful in terms of getting people to attend our meeting. And recently I posted an article on AA Agnostica about brochures/pamphlets encouraging people to create their own: Secular AA Pamphlets.

Have you thought about organizing annual workshops for agnostics and atheists in AA?

Two – not annual but biennial – workshops have already been organized for agnostics and atheists in AA in Ontario. We call them conferences or roundups. And the ones in Ontario are called SOAAR – Secular Ontario Alcoholics Anonymous Roundup. The first was held in Toronto in 2016. I was one of the organizers of the second SOAAR, held in Hamilton in 2018. (There are articles about both on AA Agnostica.)

At the one in Hamilton one on the speakers was Jeffrey Munn, the author of Staying Sober Without God. He came all the way up from California! The next SOAAR, to be organized largely by the Brown Baggers, originally scheduled for 2020, will now be held in 2022, as a result of the pandemic and so it doesn’t interfere with the International Conference of Secular AA (ICSAA) which will be held near Washington, DC, in the fall of 2021.

Would you like to say something about the situation of agnostics and atheists in AA? How do you see the near and further future?

Well, I think AA needs to grow up. It’s a bit silly to totally depend upon a book published over 80 years ago. That’s the “Conference-approved” nonsense. And it’s absolutely absurd to be ending meetings with the Lord’s Prayer and then pretending to be “spiritual, not religious”. More nonsense.

Roughly 20 years ago the growth of mainstream AA peaked, in spite of the growth of the population – and the growth in the number of alcoholics. But the growth of the secular movement within AA has been impressive. Twenty years ago there were 36 secular AA meetings worldwide. Thirty six! And now, today, there are approximately 550 secular AA meetings.

Our growth – including our regional roundups and the three International Conferences of Alcoholics Anonymous (ICSAAs) – has already had an impact on mainstream AA. So: let’s keep it up!

Onwards and upwards…

Patients taking long-term opioids produce antibodies against the drugs

University of Wisconsin-Madison scientists have discovered that a majority of back-pain patients they tested who were taking opioid painkillers produced anti-opioid antibodies. These antibodies may contribute to some of the negative side effects of long-term opioid use.

Hurricanes have names. Some climate experts say heat waves should, too

Hurricane Maria and Heat Wave Henrietta?

For decades, meteorologists have named hurricanes and ranked them according to severity. Naming and categorizing heat waves too could increase public awareness of the extreme weather events and their dangers, contends a newly formed group that includes public health and climate experts. Developing such a system is one of the first priorities of the international coalition, called the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance.

Hurricanes get attention because they cause obvious physical damage, says Jennifer Marlon, a climate scientist at Yale University who is not involved in the alliance. Heat waves, however, have less visible effects, since the primary damage is to human health.

Heat waves kill more people in the United States than any other weather-related disaster (SN: 4/3/18). Data from the National Weather Service show that from 1986 to 2019, there were 4,257 deaths as a result of heat. By comparison, there were fewer deaths by floods (2,907), tornadoes (2,203) or hurricanes (1,405) over the same period.

What’s more, climate change is amplifying the dangers of heat waves by increasing the likelihood of high temperature events worldwide. Heat waves linked to climate change include the powerful event that scorched Europe during June 2019 (SN: 7/2/19) and sweltering heat in Siberia during the first half of 2020 (SN: 7/15/20).

Some populations are particularly vulnerable to health problems as a result of high heat, including people over 65 and those with chronic medical conditions, such as neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes. Historical racial discrimination also places minority communities at disproportionately higher risk, says Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital and a member of the new alliance. Due to housing policies, communities of color are more likely to live in urban areas, heat islands which lack the green spaces that help cool down neighborhoods (SN: 3/27/09).

Part of the naming and ranking process will involve defining exactly what a heat wave is. No single definition currently exists. The National Weather Service issues an excessive heat warning when the maximum heat index — which reflects how hot it feels by taking humidity into account — is forecasted to exceed about 41° Celsius (105° Fahrenheit) for at least two days and nighttime air temperatures stay above roughly 24° C (75° F). The World Meteorological Organization and World Health Organization more broadly describe heat waves as periods of excessively hot weather that cause health problems.

Without a universally accepted definition of a heat wave, “we don’t have a common understanding of the threat we face,” Bernstein says. He has been studying the health effects of global environmental changes for nearly 20 years and is interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Defined categories for heat waves could help local officials better prepare to address potential health problems in the face of rising temperatures. And naming and categorizing heat waves could increase public awareness of the health risks posed by these silent killers.

“Naming [heat waves] will make something invisible more visible,” says climate communicator Susan Joy Hassol of Climate Communication, a project of the Aspen Global Change Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Colorado that’s not part of the new alliance. “It also makes it more real and concrete, rather than abstract.”

The alliance is in ongoing conversations with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the World Meteorological Organization and other institutions to develop a standard naming and ranking practice.

“People know when a hurricane’s coming,” Hassol says. “It’s been named and it’s been categorized, and they’re taking steps to prepare. And that’s what we need people to do with heat waves.”

Why do we miss the rituals put on hold by the COVID-19 pandemic?

For over a thousand years, the various prayers of the Catholic Holy Mass remained largely unaltered. Starting in the 1960s, though, the Catholic Church began implementing changes to make the Mass more modern. One such change occurred on November 27, 2011, when the church attempted to unify the world’s English-speaking Catholics by having them all use the same wording. The changes were slight; for instance, instead of responding to the priest’s “The Lord be with you” with “And also with you,” the response became: “And with your spirit.”

The seemingly small modification sparked an uproar so fierce that some leaders warned of a “ritual whiplash.”

The new wording has stayed intact, but that outsize reaction did not surprise ritual scholars. “The ritual reflects the sacred values of the group,” says Juliana Schroeder, a social psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Those [ritual actions] are nonnegotiable.”

But in the midst of the global coronavirus pandemic, people are being forced to renegotiate rituals large and small. Cruelly, a pandemic that has taken more than half a million lives worldwide has disrupted cherished funeral and grieving rituals.

Even when rituals can be tweaked to fit the moment, such as virtual religious services or car parades in place of graduation ceremonies, the experiences don’t carry the same emotional heft as the real thing. That’s because the immutability of rituals — their fixed and often repetitive nature — is core to their definition, Schroeder and others say. So too is the symbolic meaning people attach to behaviors; doing the ritual “right” can matter more than the outcome.

Why do such behaviors even exist? Anthropologists, psychologists and neuroscientists have all weighed in, so much so that the theories used to explain the purpose of rituals feel as myriad as the forms rituals have taken the world over.

That growing body of research can help explain the unrest people are now experiencing as beloved rituals go virtual or get punted to some unsettled future. Multiple lines of evidence suggest, for instance, that rituals help with emotional regulation, particularly during periods of uncertainty, when control over events is not within reach. Rituals also foster social cohesion. Engaging in rituals, in other words, could really help people and societies navigate this new and fraught global landscape.

“This is exactly the time … when we want to be able to congregate with other people, get social support and engage in the kinds of collective rituals that promote cooperation [and] reduce anxiety,” says developmental psychologist Cristine Legare of the University of Texas at Austin. And yet, with COVID-19, congregating in any sort of group can be downright dangerous. What does that mean for how we persevere?

An illusion of control

Polish-born British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski documented rituals and speculated on their reason for being in the early 1900s. Living among fishermen on the Trobriand Islands off New Guinea from 1915 to 1918, Malinowski noticed that when the fishermen stuck to the safe and reliable lagoon, they described their successes and failures in terms of skill and knowledge.

But when venturing into deeper waters, the fishermen practiced rituals during all stages of the journey, acts Malinowski collectively referred to as “magic.” Before setting out, the men consumed special herbs and sacrificed pigs. While on the water, the fishermen beat the canoe with banana leaves, applied body paint, blew on conch shells and chanted in synchrony. Malinowski later used that Trobriand data to comment more broadly on human behavior.

“We find magic wherever the elements of chance and accident, and the emotional play between hope and fear, have a wide and extensive range. We do not find magic whenever the pursuit is certain, reliable and well under control of rational methods,” Malinowski wrote in an essay published posthumously in 1948.

Working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, American anthropologist Roy Rappaport built on that idea by developing a social framework for ritual, theorizing that such behaviors help individuals and groups maintain a balanced psychological state — much like a thermostat system that controls when the heat kicks on. In recent decades, anthropologists and psychologists have tested the idea that rituals regulate emotions.

In 2002, during a period of intense fighting between Palestine and Israel, anthropologist Richard Sosis took a taxi from Jerusalem to Tzfat, in northern Israel. Sosis, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs, noticed that the driver was carrying the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms despite professing little religious inclination and admitting he didn’t read it. The driver said the book was there for his protection. Sosis suspected that the mere presence of the book helped the cabdriver manage the stress of possibly violent encounters. But how?

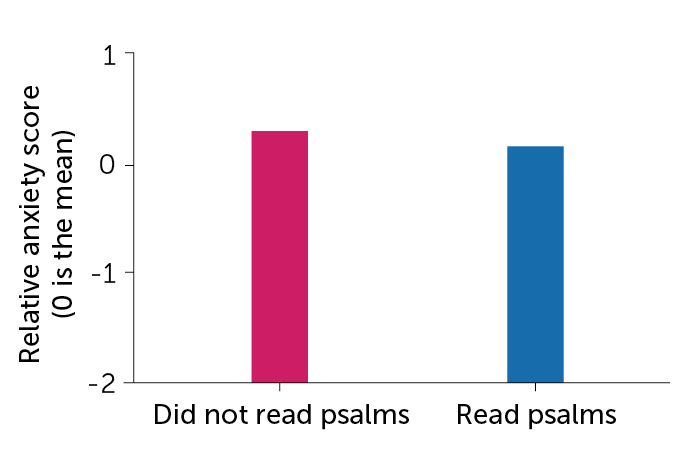

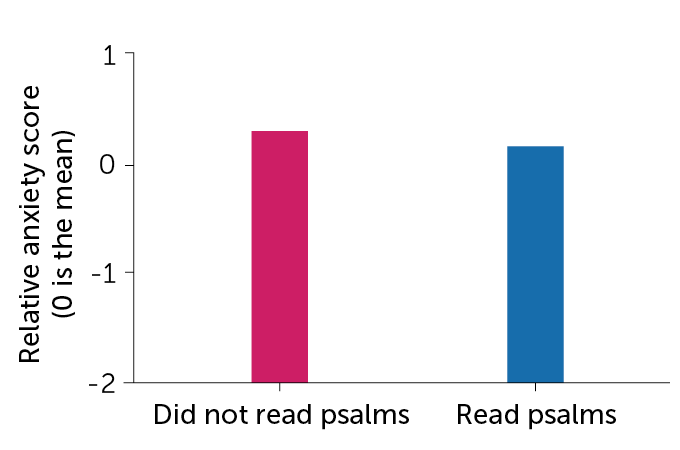

A few years later, Sosis and his team recruited 115 Orthodox Jewish women from Tzfat to take part in a study about psalm reading. By the time interviews began in August 2006, war between Israel and Lebanon’s Hezbollah had broken out; 71 percent of the women in the study had fled Tzfat for central Israel.

The researchers asked the women to list their three top stressors during the war. The women listed many of the same issues, with a few important differences. Almost 76 percent of those who stayed in Tzfat reported concerns about property damage compared with just 11 percent of women who left. Women who left were more likely than women who stayed to worry about stressors associated with displacement, such as inadequate child care (32 percent versus 9 percent) and a lack of schedule (32 percent compared with 6 percent).

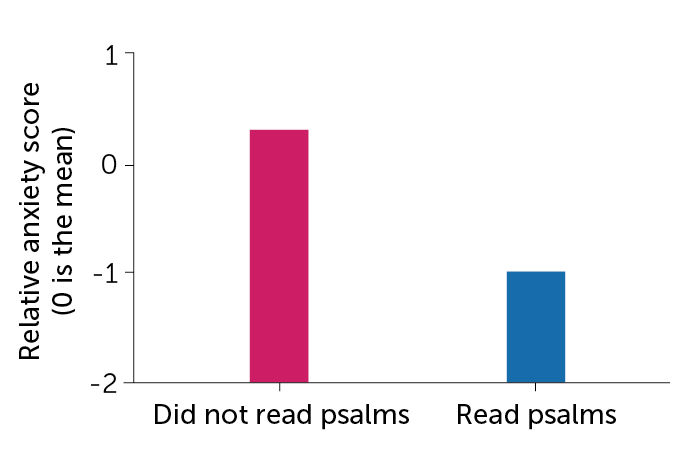

The researchers also had the women fill out a questionnaire about anxiety. Psalm reading provided anxiety relief, but the psalms’ true power depended on the women’s location. That is, the anxiety scores of women who left Tzfat and recited psalms were only slightly lower than the scores of women who left but did not recite psalms. The anxiety scores of women who stayed in Tzfat and recited psalms, on the other hand, were more than 50 percent lower than women who stayed and did not recite psalms. Overall, those who remained in Tzfat and recited psalms had lower anxiety scores than those who left.

“Reciting the psalms was effective under conditions in which the stressor was uncontrollable. But once you could devise instrumental solutions to a problem, such as taking care of your kids or finding work, reciting psalms isn’t going to fix anything,” says Sosis, whose findings appeared in American Anthropologist in 2011. Several more recent studies conducted on individuals living in war and earthquake zones mirror Sosis’ finding that rituals give participants a sense — or a comforting illusion — of control over the uncontrollable.

Testing the illusion

In recent years, researchers have begun testing the psychological benefits of rituals using controlled experiments and physiological monitors. In one study, Dimitris Xygalatas, an anthropologist and psychologist also at the University of Connecticut, and colleagues recruited 74 Hindu women in southwest Mauritius. Thirty-two women were sent to a lab and the rest to the local temple. All participants completed a survey evaluating their overall anxiety and were fitted with heart rate monitors.

Researchers elicited anxiety among the women by giving them three minutes to put together a speech on their flood preparedness — natural disasters are a common threat to the island — to ostensibly be evaluated later by government experts.

Afterward, women at the temple performed their usual routine — praying to Hindu deities and offering fruits and flowers. These actions tended to follow the same pattern across participants, such as holding an oil lamp or incense stick and moving it slowly clockwise before the statue of a deity. Women at the lab, meanwhile, sat quietly for 11 minutes, about the same time it took for the other women to pray. All participants then took a second anxiety survey.

On the first survey, both groups reported similar levels of anxiety. But the women who then performed their rituals at the temple reported half as much anxiety as the women in the lab.

That divergence also showed up on the heart monitors, specifically on a marker for resilience known as heart rate variability. During periods of stress, heart rate becomes less variable and the time between beats gets shorter.

Spacing between heartbeats for women who sat quietly increased only about 3 percent from the baseline rate, measured when the women first arrived at the lab. But for women who performed the ritual and experienced stress reduction, the space between beats lengthened 22 percent from the baseline rate, Xygalatas and colleagues reported in the Aug. 17 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. That is, heart rate variability was 30 percent higher among women performing the ritual than women who sat quietly.

Xygalatas’ and Sosis’ studies suggest that engaging in the individual, repetitive rituals often seen in religious practices, such as reading psalms or reciting prayers, could serve as a balm during the pandemic. But, typically, even individual rituals carry a social component. For instance, it was common for women in Sosis’ study to divvy up the 150 passages so that they could read the entire Book of Psalms in a single day. “Women recognize that other women are also engaging in these psalm-recitation activities,” Sosis says.

Researchers largely concur that the power of rituals rests within a larger social fabric. Rituals “are created by groups, and individuals inherit them,” Legare says. The problem is, during the pandemic, even if people are engaging in rituals on their own, those larger groups are now fractured.

Merging with the in-group

The idea that rituals serve to bond individuals is not new. Fourteenth century scholar Ibn Khaldūn used the term asabiyah, Arabic for solidarity, to describe the social cohesion that emerges from engaging in collective rituals. Khaldūn believed that solidarity had its foundations in kinship but extended to tribes and even nations. Centuries later, in the early 1900s, French sociologist Émile Durkheim theorized that group rituals fostered unity among practitioners.

In contemporary times, researchers have sought to understand the ways in which rituals bind people together. Work by University of Oxford anthropologist Harvey Whitehouse suggests that rituals exist on either side of a dichotomy. On one side are “imagistic” rituals that fuse people together, often more tightly than kin, through intense moments and painful rites of passage, such as piercing or tattooing one’s body and walking on fire.

Today, imagistic rituals are much less common than the “doctrinal” rituals that characterize modern-day life — prayers, religious services and various regimented rites of passage, such as baby showers and birthday parties. Such rituals appear to have become established as societies grew increasingly complex with the emergence of agriculture. While not binding people as tightly as imagistic rituals, doctrinal rituals enable group members to both identify those in their larger group and spot and police social deviants, Whitehouse says.

Several studies of contemporary communities support the idea that doctrinal rituals help unite social groups. In the early 2000s, Sosis compared cooperation among members of secular versus religious collective farming settlements, called kibbutzim, in Israel. The two types of kibbutzim operated in similar ways, except that men in the religious settlements were required to pray in groups of 10 or more people at least three times a day. Women also prayed, but did not have to do so collectively. Sosis reported in Current Anthropology in 2003 that members of religious kibbutzim were more cooperative, as evidenced by taking less money out of a communal pot, than members of secular kibbutzim. That difference was driven entirely by those ritual-practicing men in the religious kibbutzim.

In her research, Legare — who invents rituals to see how children understand such practices — has shown that children use rituals to identify and reinforce connections with members of their own group while shunning those outside the group. Recently, Legare, working with Nicole Wen, now at Brunel University London, divided 60 children, ages 4 to 11, into two groups. The children were given wristbands denoting their group’s color. One group was then walked through a highly scripted, ritualized process to make a bead necklace with prompts like: “First, hold up a green string. Then, touch a green star to your head. Then, string on a green star” and so on. The other group made necklaces with the same materials, but no script.

The activities continued for two weeks, during which the researchers measured how long children spent comparing their handiwork to that of members of their own group and how long they spent watching members of the other group, such as by looking over their shoulders. Reporting in the Aug. 17 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, the team found that during the experiment, children in the ritual group spent on average twice as much time as children in the nonritual group showing off their necklaces to members of their own group and monitoring the behavior of those not in the group.

Working in a group helps people bond even without a script to follow, Legare says. But “rituals take the effects of a group experience and turn them way up.”

Legare’s project and others also illustrate how rituals engender in-groups and out-groups. Whitehouse’s work suggests that shared traumatic experiences, which may include imagistic rituals, contribute to the cohesion of terrorist cell networks, where fighters would sooner die for fellow fighters than even family (SN: 7/9/16, p. 18).

The pandemic itself is the latest example of how a shared traumatic experience and the resulting rituals — Zoom parties, alliances around wearing or eschewing masks and reactions to civil rights rallies — can break or bind communities.

“Human social groups … [are] always going to be vulnerable to in-group preferences and out-group biases,” Legare says. Whether we use ritual for good — or evil — is up to us.

Pandemic asynchrony

Certain rituals, such as singing and dancing together, are particularly good at amplifying group cohesion and a spirit of generosity. But these group rituals, tragically, also can spread the coronavirus.

On March 10 in Skagit County, Wash., 61 members of a church choir met for practice. One singer, who had been feeling unwell for a few days, later tested positive for COVID-19. Within weeks, almost 90 percent of those in attendance had developed similar symptoms, with 33 confirmed cases; two members died from the disease. Similar stories linking choir practice to superspreading events have emerged. And the collective singing that characterizes so many religious services has emerged as a particularly risky activity in this pandemic.

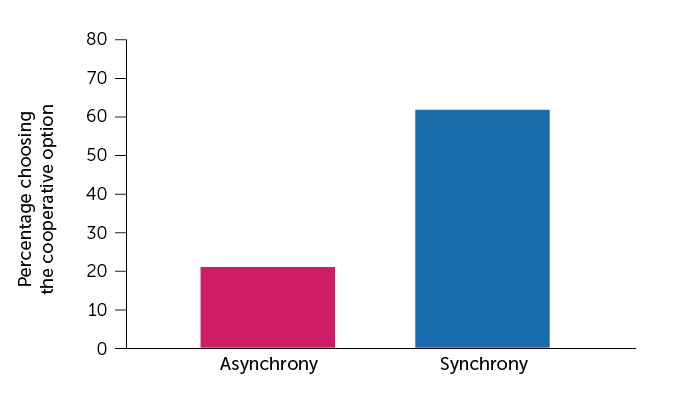

In a series of experiments reported in 2013, researchers tested to see if dancing or chanting together made people feel more generous toward members of their group. One of the tests divided 27 volunteers into groups of three and handed them a list of one-syllable words divided into three columns. The researchers told some of the groups to go down the list and chant the words together for six minutes, keeping in beat with a metronome — effectively a ritual performed in synchrony. Other groups recited the words sequentially, with each member reading the words in only one column.

The participants then played a cooperative game within their groups. Anonymously, each member could choose either option X, a guaranteed prize of $7, or option Y, a prize of $10 that came through only if every group member chose Y. If a single member chose X, no one would get money. Reporting in PLOS ONE, the researchers found that 62 percent of participants who chanted together chose Y compared with just 21 percent who chanted in sequence.

Other synchronized activities, such as marching, dancing, rowing and even collective social distancing while out in public, can bond participants, Whitehouse says. The alliance forged by synchrony is arguably playing out across the United States even now as both Black and non-Black people march and chant in unison to protest police brutality and systemic racism. In any context, Legare says, synchrony “is a powerful social catalyst.”

New rituals

Ironically, as the pandemic makes practicing rituals, particularly social rituals, profoundly challenging, decades of research have made clear that people turn to such regimented behaviors during periods of unrest. “Anthropologists have long observed that during times of anxiety, you see spikes in ritual activity,” Xygalatas says.

So even as rituals are being disrupted and diluted, people are seeking new sources of solace. Many people, for instance, are turning to their immediate family members to fill that ritual void.

“It’s possible that lockdowns are actually leading to the invention of new family rituals that foster this kind of resilience, ranging from the arrangement of rainbows and teddy bears in windows to the revival of more traditional family rituals like eating, singing [and] telling stories together,” Whitehouse says.

People are also finding new ways to experience old traditions. Rachel Fraumann, a Methodist minister in Barre, Vt., says online attendance at her recorded sermons has more than doubled since mid-March. In her view, now is a great time for the ritually and spiritually adrift to shop around for their ritual fit.

Such “shopping” doesn’t need to occur within a religious context. Secular rituals, such as those centered around crafts, music or sports, have shown similar promises, and pitfalls, as religious activities, says Oxford cognitive anthropologist Martha Newson. Which means now could be a great time to try new hobbies with a solo component as a way to practice in the here and now, with a group component to look forward to after the pandemic ends, such as knitting with the goal of joining a knitting circle or buying a rowing machine to get fit enough to join the local crew team, where bodies move in sync.

Creating rituals outside of religion, though, can be hard to get right. “It’s not the hobby, it’s the people who do the hobby who make the tribe. Precisely what the magic ingredients are for that, we [don’t] know,” Newson says.

Those challenges won’t stop people from trying once the pandemic ends, Legare says. “I would predict that there will be an increase in attending religious services but [also] an increase in attending all kinds of social group activities. People are so starved for social interaction, I would predict increased enrollment in absolutely everything.”

‘Is This When I Drop Dead?’ Two Doctors Report From the COVID Front Lines

Health workers across the country looked on in horror when New York became the global epicenter of the coronavirus. Now, as physicians in cities such as Houston, Phoenix and Miami face their own COVID-19 crises, they are looking to New York, where the caseload has since abated, for guidance.

The Guardian sat in on a conversation with two emergency room physicians — one in New York and the other in Houston — about what happened when COVID-19 arrived at their hospitals.

Dr. Cedric Dark, Houston: When did you start worrying about how COVID-19 would impact New York?

Dr. Tsion Firew, New York: Back in February, I traveled to Sweden and Ethiopia for work. There was some sort of screening for COVID-19 in both places. On Feb. 22, I came to New York City, and nothing — no screening. At that point, I thought, “I don’t think this country’s going to handle this well.”

Dark: On Feb. 26, at a department meeting, one of my colleagues put coronavirus on the agenda. I thought to myself, “Why do we even need to bother with this here in Houston? This is in China; maybe it’s in Europe?”

Firew: On March 1, we had our first case in New York City, which was at my hospital. Fast-forward 15 days and I get a call saying, “Hey, you were exposed to COVID-positive patients.” I was told to stay home.

Dark: My anxiety grew as I saw what was happening in Italy, a country I’ve visited several times. I remember seeing images of people dying in their homes and mass graves. I started to wonder, “Is this what we’ll see over here? Are my colleagues going to be dying? Is this something that’s going to get me or my wife, who’s also an ER doctor? Are we going to bring it home to our son?”

In March, we repurposed our urgent care pod, which has eight beds, into our coronavirus unit. And for a while, that was enough.

Firew: In late March, health workers without symptoms were told to come back to work. It felt like a tsunami hit. I’ve practiced in very low-resource settings and even in a war zone, and I couldn’t believe what I was witnessing in New York.

The emergency department was silent — there were no visitors, and patients were very sick. Many were on ventilators or getting oxygen. The usual human interactions were gone. Everybody was wearing a mask and gowns and there were so many people who came to help from different places that you didn’t know who was who. I spent a lot more time on the phone talking to family members about end-of-life care decisions, conversations you’d normally have face-to-face.

In New York, the severity of the crisis really depended on what hospital you were at. Columbia has two hospitals — one at 168th and one at 224th — and the difference was night and day. The one on 224th is smaller and just across the bridge from the Bronx, which was hit hard by the virus.

There, people were dying in ambulances while waiting for care. The emergency department was overwhelmed with patients who needed oxygen. Its hallways were crowded with patients on portable oxygen tanks. We ran out of monitors and oxygen for the portable tanks. Staff members succumbed to COVID-19, exacerbating shortages of nurses and doctors.

My friends who work in Lower Manhattan couldn’t believe some of the things we saw.

Dark: I went to medical school at NYU and have a lot of friends in New York I was checking in with at the time. I thought that in Houston, a city that’s almost as big, we had the conditions for a similar crisis: It’s a large city with an international airport, it attracts a lot of business travelers, and thousands of people come here each March for the rodeo.

In late March, a guy about my age came into the hospital. It was the first day we got coronavirus tests. A few days later, a nurse texted me that the patient had tested positive. He hadn’t traveled anywhere — it was proof to me that we had community transmission in Houston before any officials admitted it.

You became infected, right?

Firew: In early April, I became sick, along with my husband. I never imagined that in 2020 I would be writing out a living will detailing my life insurance policy to my family. Walking from my bed to the kitchen would make my heart race; I often wondered: Is this when I drop dead like my patient the other day?

A few days before I got sick, the president had said that anybody who wanted a test could get one. But then I was on the phone with my workplace and with the department of health begging for a test.

It was also around that time that a brown-skinned physician who was about my age died from COVID-19. So I knew being in my mid-30s wouldn’t protect me. I was even more worried when my husband became ill because, as a Black man, his chances of dying from this disease were much higher than mine. We both recovered, but I still have some fatigue and shortness of breath.

When did cases pick up in Houston?

Dark: We saw a gradual increase in cases throughout April, but it stayed relatively calm because the city was shut down. The hospital was kind of a ghost town because no one was having elective procedures. Things were quiet until Texas reopened in May.

I remember when I lost my first COVID patient. He started to crash right in front of me. We started CPR and I ran the algorithms through my mind trying to think how we could bring him back, but kept ending up at the same conclusion: This is COVID and there’s nothing I can do.

It’s like serving on the front lines of a war. We initially struggled to find our own personal protective equipment while the hospitals worked to secure the supply chain. Although that situation has stabilized, a lot of patients who come in for non-COVID reasons wind up testing positive. COVID is everywhere.

Our patient population is heavily Latino and Black and, for a time, our hospital had some of the highest numbers of COVID cases among the nearly two dozen hospitals in the Texas Medical Center network. It’s revealed the fault lines of a preexisting issue in terms of inequities in health care.

As area hospitals fill up, they reallocate additional floors to COVID patients. Who knows, if we don’t get this under control, maybe one day the whole hospital will be COVID.

Firew: Now I’m just chronically angry. The negligence came from the top all the way down. Our leaders do not lead with evidence — we knew what was going to happen when states reopened so quickly.

Dark: Yeah, this was completely avoidable, had the governor [Texas Gov. Greg Abbott] decided not to open up the economy too fast.

How are things in New York now?

Firew: There have been several days where I’ve seen zero COVID cases. If I do see a case, it’s usually someone who has traveled from abroad or other states.

People are coming in for non-COVID reasons. Recently, a woman in her early 40s came in with a massive lesion on her breast. She’d started experiencing some pain three months ago, during the peak of the pandemic, and was too frightened to come to the hospital. To make matters worse, she didn’t have insurance and couldn’t afford the telehealth that many had access to.

By the time she made it to our hospital, the mass had metastasized to her spine and lungs. Even with aggressive treatment, she likely only has a few months to live. This is one of the many cases we’re seeing now that we are back to “normal” — complications of chronic illnesses and delayed diagnoses of cancer. The burden of the pandemic layered with a broken health care system.

Dr. Tsion Firew is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Columbia University and special adviser to the minister of health of Ethiopia.

Dr. Cedric Dark is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and a board member for Doctors for America.

This conversation was condensed and edited by Danielle Renwick.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

COVID Data Failures Create Pressure for Public Health System Overhaul

After terrorists slammed a plane into the Pentagon on 9/11, ambulances rushed scores of the injured to community hospitals, but only three of the patients were taken to specialized trauma wards. The reason: The hospitals and ambulances had no real-time information-sharing system.

Nineteen years later, there is still no national data network that enables the health system to respond effectively to disasters and disease outbreaks. Many doctors and nurses must fill out paper forms on COVID-19 cases and available beds and fax them to public health agencies, causing critical delays in care and hampering the effort to track and block the spread of the coronavirus.

“We need to be thinking long and hard about making improvements in the data-reporting system so the response to the next epidemic is a little less painful,” said Dr. Dan Hanfling, a vice president at In-Q-Tel, a nonprofit that helps the federal government solve technology problems in health care and other areas. “And there will be another one.”

There are signs the COVID-19 pandemic has created momentum to modernize the nation’s creaky, fragmented public health data system, in which nearly 3,000 local, state and federal health departments set their own reporting rules and vary greatly in their ability to send and receive data electronically.

Sutter Health and UC Davis Health, along with nearly 30 other provider organizations around the country, recently launched a collaborative effort to speed and improve the sharing of clinical data on individual COVID cases with public health departments.

But even that platform, which contains information about patients’ diagnoses and response to treatments, doesn’t yet include data on the availability of hospital beds, intensive care units or supplies needed for a seamless pandemic response.

The federal government spent nearly $40 billion over the past decade to equip hospitals and physicians’ offices with electronic health record systems for improving treatment of individual patients. But no comparable effort has emerged to build an effective system for quickly moving information on infectious disease from providers to public health agencies.

In March, Congress approved $500 million over 10 years to modernize the public health data infrastructure. But the amount falls far short of what’s needed to update data systems and train staff at local and state health departments, said Brian Dixon, director of public health informatics at the Regenstrief Institute in Indianapolis.

The congressional allocation is half the annual amount proposed under last year’s bipartisan Saving Lives Through Better Data Act, which did not pass, and much less than the $4.5 billion Public Health Infrastructure Fund proposed last year by public health leaders.

“The data are moving slower than the disease,” said Janet Hamilton, executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. “We need a way to get that information electronically and seamlessly to public health agencies so we can do investigations, quarantine people and identify hot spots and risk groups in real time, not two weeks later.”

The impact of these data failures is felt around the country. The director of the California Department of Public Health, Dr. Sonia Angell, was forced out Aug. 9 after a malfunction in the state’s data system left out up to 300,000 COVID-19 test results, undercutting the accuracy of its case count.

Other advanced countries have done a better job of rapidly and accurately tracking COVID-19 cases and medical resources while doing contact tracing and quarantining those who test positive. In France, physicians’ offices report patient symptoms to a central agency every day. That’s an advantage of having a national health care system.

“If someone in France sneezes, they learn about it in Paris,” said Dr. Chris Lehmann, clinical informatics director at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Coronavirus cases reported to U.S. public health departments are often missing patients’ addresses and phone numbers, which are needed to trace their contacts, Hamilton said. Lab test results often lack information on patients’ races or ethnicities, which could help authorities understand demographic disparities in transmission and response to the virus.

Last month, the Trump administration abruptly ordered hospitals to report all COVID-19 data to a private vendor hired by the Department of Health and Human Services rather than to the long-established reporting system run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The administration said the switch would help the White House coronavirus task force better allocate scarce supplies.

The shift disrupted, at least temporarily, the flow of critical information needed to track COVID-19 outbreaks and allocate resources, public health officials said. They worried the move looked political in nature and could dampen public confidence in the accuracy of the data.

An HHS spokesperson said the transition had improved and sped up hospital reporting. Experts had various opinions on the matter but agreed that the new system doesn’t fix problems with the old CDC system that contributed to this country’s slow and ineffective response to COVID-19.

“While I think it’s an exceptionally bad idea to take the CDC out of it, the bottom line is the way CDC presented the data wasn’t all that useful,” said Dr. George Rutherford, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California-San Francisco.

The new HHS system lacks data from nursing homes, which is needed to ensure safe care for COVID patients after discharge from the hospital, said Dr. Lissy Hu, CEO of CarePort Health, which coordinates care between hospitals and post-acute facilities.

Some observers hope the pandemic will persuade the health care industry to push faster toward its goal of smoother data exchange through computer systems that can easily talk to one another — an objective that has met with only partial success after more than a decade of effort.

The case reporting system launched by Sutter Health and its partners sends clinical information from each coronavirus patient’s electronic health record to public health agencies in all 50 states. The Digital Bridge platform also allows the agencies for the first time to send helpful treatment information back to doctors and nurses. About 20 other health systems are preparing to join the 30 partners in the system, and major digital health record vendors like Epic and Allscripts have added the reporting capacity to their software.

Sutter hopes to get state and county officials to let the health system stop sending data manually, which would save its clinicians time they need for treating patients, said Dr. Steven Lane, Sutter’s clinical informatics director for interoperability.

The platform could be key in implementing COVID-19 vaccination around the country, said Dr. Andrew Wiesenthal, a managing director at Deloitte Consulting who spearheaded the development of Digital Bridge.

“You’d want a registry of everyone immunized, you’d want to hear if that person developed COVID anyway, then you’d want to know about subsequent symptoms,” he said. “You can only do that well if you have an effective data system for surveillance and reporting.”

The key is to get all the health care players — providers, insurers, EHR vendors and public health agencies — to collaborate and share data, rather than hoarding it for their own financial or organizational benefit, Wiesenthal said.

“One would hope we will use this crisis as an opportunity to fix a long-standing problem,” said John Auerbach, CEO of Trust for America’s Health. “But I worry this will follow the historical pattern of throwing a lot of money at a problem during a crisis, then cutting back after. There’s a tendency to think short term.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Back to Life: COVID Lung Transplant Survivor Tells Her Story

Mayra Ramirez remembers the nightmares.

During six weeks on life support at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, Ramirez said, she had terrifying nightmares that she couldn’t distinguish from reality.

“Most of them involve me drowning,” she said. “I attribute that to me not being able to breathe, and struggling to breathe.”

On June 5, Ramirez, 28, became the first known COVID-19 patient in the U.S. to undergo a double lung transplant. She is strong enough now to begin sharing the story of her ordeal.

Mysterious Exposure

Before the pandemic, Ramirez worked as a paralegal for an immigration law firm in Chicago. She enjoyed walking her dogs and running 5K races.

Ramirez had been working from home since mid-March, hardly leaving the house, so she has no idea how she contracted the coronavirus. In late April, she started experiencing chronic spasms, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell, and a slight fever.

“I felt very fatigued,” Ramirez said. “I wasn’t able to walk long distances without falling over. And that’s when I decided to go into the emergency room.”

From the ER to a Ventilator

The staff at Northwestern checked her vitals and found her oxygen levels were extremely low. She was given 10 minutes to explain her situation over the phone to her mother in North Carolina and appoint her to make medical decisions on her behalf.

Ramirez knew she was about to be placed on a ventilator, but she didn’t understand exactly what that meant.

“In Spanish, the word ‘ventilator’ — ventilador — is ‘fan,’ so I thought, ‘Oh, they’re just gonna blow some air into me and I’ll be OK. Maybe have a three-day stay, and then I’ll be right out.’ So I wasn’t very worried,” Ramirez said.

In fact, she would spend the next six weeks heavily sedated on that ventilator and another machine — known as ECMO, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation — pumping and oxygenating her blood outside of her body.

One theory about why Ramirez became so sick is that she has a neurological condition that is treated with steroids, drugs that can suppress the immune system.

By early June, Ramirez was at risk of further decline. She began showing signs that her kidneys and liver were starting to fail, with no improvement in her lung function. Her family was told she might not make it through the night, so her mother and sisters caught the first flight from North Carolina to Chicago to say goodbye.

When they arrived, the doctors told Ramirez’s mother, Nohemi Romero, that there was one last thing they could try.

Ramirez was a candidate for a double lung transplant, they said, although the procedure had never been done on a COVID patient in the U.S. Her mother agreed, and within 48 hours of being listed for transplant, a donor was found and the successful procedure was performed on June 5.

At a recent news conference held by Northwestern Memorial, Romero shared in Spanish that there were no words to describe the pain of not being by her daughter’s side as she struggled for her life.

She thanked God all went well, and for giving her the strength to make it through.

‘I Just Felt Like a Vegetable’

Dr. Ankit Bharat, Northwestern Medicine’s chief of thoracic surgery, performed the 10-hour procedure.

“Most patients are quite sick going into [a] lung transplant,” Bharat said in an interview in June. “But she was so sick. In fact, I can say without hesitation, the sickest patient I ever transplanted.”

Bharat said most COVID-19 patients will not be candidates for transplants because of their age and other health conditions that decrease the likelihood of success. And early research shows that up to half of COVID patients on ventilators survive the illness and are likely to recover on their own.

But for some, like Ramirez, Bharat said, a transplant can be a lifesaving option of last resort.

When Ramirez woke up after the operation, she was disoriented, could barely move her body and couldn’t speak.

“I just felt like a vegetable. It was frustrating, but at the time I didn’t have the cognitive ability to process what was going on,” Ramirez said.

She recalled being sad that her mother wasn’t with her in the hospital, not understanding that visitors weren’t allowed because of the pandemic.

Her family had sent photos to post by her hospital bed, and Ramirez said she couldn’t recognize anyone in the pictures.

“I was actually sort of upset about it, [thinking,] ‘Who are these strangers and why are their pictures in my room?’” Ramirez said. “It was weeks later, actually, that I took a second look and realized, ‘Hey, that’s my grandmother. That’s my mom and my siblings. And that’s me.”

After a few weeks, Ramirez said, she finally understood what happened to her. When COVID-19 restrictions loosened at the hospital in mid-June, her mother was finally able to visit.

“The first thing I did was just tear up,” Ramirez said. “I was overjoyed to see her.”

The Long Road to Recovery

After weeks of inpatient rehabilitation, Ramirez was discharged home. She’s now receiving in-home nursing assistance as well as physical and occupational therapy, and she’s working on finding a psychologist.

Ramirez eagerly looks forward to being able to spend more time with her family, her boyfriend and her dogs and serving the immigrant community through her legal work.

But for now, her days are consumed by rehab. Her doctors say it will be at least a year before she can function independently and be as active as before.

Ramirez is slowly regaining strength and learning how to breathe with her new lungs.

She takes more than 17 pills, four times a day, including medicines to prevent her body from rejecting the new lungs. She also takes anxiety meds and antidepressants to help her cope with daily nightmares and panic attacks.

The long-term physical and mental health tolls on Ramirez and other COVID-19 survivors remain largely unknown, since the virus is so new.

While most people who contract the virus are left seemingly unscathed, for some patients, like Ramirez, the road to recovery is full of uncertainty, said Dr. Mady Hornig, a physician-scientist at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Some patients can experience post-intensive care syndrome, or PICS, which can consist of depression, memory issues and other cognitive and mental health problems, Hornig said. Under normal circumstances, ICU visits from loved ones are encouraged, she said, because the human interaction can be protective.

“That type of contact would normally keep people oriented … so that it doesn’t become as traumatic,” Hornig said.

Hopes for the Future

COVID-19 has disproportionately harmed Latino communities, as Latinos are overrepresented in jobs that expose them to the virus and have lower rates of health insurance and other social protections.

Ramirez has health insurance, although that hasn’t spared her from tens and thousands of dollars’ worth of medical bills.

And even though she still ended up getting COVID-19, she counts herself lucky for having a job that allowed her to work from home when the pandemic struck. Many Latino workers don’t have that luxury, she said, so they’re forced to risk their lives doing low-wage jobs deemed essential at this time.

Ramirez’s mother is a breast cancer survivor, making her particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. She had been working at a meatpacking plant in North Carolina, for a company that Ramirez said has had hundreds of COVID-19 cases among employees.

So Ramirez is relieved to have her mom in Chicago, helping take care of her.

“I’m glad this is taking her away from her position,” Ramirez said.

Friends and family in North Carolina have been fundraising to help pay her medical bills, selling raffle tickets and setting up a GoFundMe page on her behalf. Ramirez is also applying for financial assistance from the hospital.

Her experience with COVID-19 has not changed who she is as a person, she said, and she looks forward to living her life to the fullest.

If she ever gets the chance to speak with the family of the person whose lungs she now has, she said, she will thank them “for raising such a healthy child and a caring person [who] was kind enough to become an organ donor.”

Her life may never be the same, but that doesn’t mean she won’t try. She laughs as she explains how she asked her surgeon to take her skydiving someday.

“Dr. Bharat actually used to work at a skydiving company when he was younger,” Ramirez said. “And so he promised me that, hopefully within a year, he could get me there.”

And she has every intention of holding him to that promise.

This story is part of a reporting partnership that includes Illinois Public Media, Side Effects Public Media, NPR and KHN.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Leaving Jail, Addicts Face Growing Opioid Crisis During Pandemic

In April, Rob Camidge was released from a short stint in jail and right into a pandemic. A recovering heroin addict with long stints of sobriety, Camidge knew the routine that helped to keep him clean: Working. Going to the gym. And three times a week, visiting an outpatient program where his urine was tested.

Now, due to COVID-19, there was no work. The gym was closed. And his recovery program moved online, sans drug tests. Narcotics Anonymous meetings via Zoom “don’t feel real,” he said. “There’s nothing like talking to someone across from you, looking from eye to eye.”

Besides, he was isolated from his friends and family on the Jersey Shore—and idle. “I can’t do what I normally do,” he said. “So what I know best is getting high.” And without in-person drug screenings, he figured “no one knows, the only person who knows is me…It’s only going to be this one time.”

Camidge got what he calls “the stinkin’ thinkin’” and began using heroin again in June before finally getting into a rehabilitation program. He’s now clean, living at a halfway house in Newark. And he’s finding a semblance of stability at a nonprofit for the formerly incarcerated called the New Jersey Reentry Corporation, where those who have dealt with incarceration and addiction are pouring into their offices, telling stories about how the recent pandemic worsened the health emergency that was already here: opioid addiction.

Early government data from throughout the region show a spike in suspected drug overdose deaths since the lockdown began in March. Deaths in New Jersey were up 15 percent from March to June, compared to the same period last year. In 2019 overdose deaths in New Jersey totaled 3,021—a slight decrease from the year before. But any progress appears to be wiped away in 2020. There were 309 deaths in May alone, compared to 248 in May 2019.

Queens saw a 56 percent spike in overdose deaths during the first five months of the year. In Staten Island, the 58 overdose fatalities so far this year represent an increase from 49 at this time last year (though a spokesperson from the district attorney’s office said the numbers are preliminary and could change).

Another indicator: Emergency Medical Technicians in New York City administered naloxone, the drug used to revive those who overdose on heroin, 23 percent more often than last year, according to NY1. Unlike in New Jersey, which maintains an online overdose tracker, neither the state or city health departments in New York said it had public data about overdose deaths in 2020.

Nationally, a White House drug policy office analysis showed an 11.4 percent increase in fatalities during the first four months of the year, while a New York Times analysis estimated the increase to be 13 percent.

When the coronavirus epidemic first began to take hold in March, President Trump presaged the problem. “You will see drugs being used like nobody has ever used them before,” he said. “And people are going to be dying all over the place from drug addiction, because you would have people that had a wonderful job at a restaurant, or even owned a restaurant.”

Those struggling in recovery and the network of people who work with them describe myriad reasons for the spike in overdose deaths during COVID:

- A pause in drug screenings at outpatient facilities meant that those in recovery weren’t being held as accountable for staying off drugs.

- In-patient drug treatment facilities halted or limited in-take to preserve social distance. The New York State Office of Addiction Services and Support even advised that admissions be reduced.

- Group therapy sessions could no longer be held, leading to therapy via Zoom—which requires that patients have a video-enabled device. Such sessions also lack the human interaction many struggling with addiction require.

- Quarantine-imposed social isolation and separation from friends and family not only exacerbated some of the mental health challenges associated with addiction, but it led some heroin-addicted people to use alone, with no one there to revive them with naloxone or call 9-1-1 if they overdosed.

- Government offices were closed, so those leaving prison on drug charges had a harder time accessing housing, food and other public benefits, leading to a sense of desperation that can trigger relapses.

- Many doctors’ offices, where suboxone is prescribed to help people get off heroin, closed.

- The economic crisis has made jobs and affordable housing scarcer, especially for those re-entering the community.

- Fentanyl, an opioid far deadlier than heroin, is becoming increasingly common on the streets.

Jim McGreevey, former governor of New Jersey and now the chairman of the New Jersey Reentry Corporation, has spent much of the last 16 years since he left office ministering to prisoners and running nonprofits that assist those leaving incarceration.

“Some people suffer COVID watching Netflix; other people suffer COVID being out in the street worrying about how they’re going to eat, where they’re going to sleep,” McGreevey said to a group gathered at the nonprofit’s facility in Paterson on a recent Monday morning. “The stack is already against [those struggling with addiction] on so many levels, but COVID just made it worse, COVID made it almost insufferable.”

And yet, as the need increases to help the formerly incarcerated with addiction recovery, government support is in peril. McGreevey laid off 10 percent of his staff due to state budget cuts, and without more funds, he said his Paterson office could close this fall.

“We’ll spend a fortune to keep people locked up in prison, but we don’t do much to help people when they come out of prison in terms of addiction treatment, in terms of employment,” he said.

Budget cuts are playing out similarly in New York, where lawmakers are alarmed by a possible 31 percent reduction in drug treatment funding. Advocates for drug treatment say the federal government needs to provide emergency relief to mental health and addiction services, but little has been appropriated.

The irony of COVID is it prompted officials to release scores of incarcerated people—like those held on drug crimes—in order to prevent the spread of the virus behind bars. But without jobs or treatment programs waiting for them, they weren’t necessarily better off on the outside.

Rev. Wilfredo Toro, head chaplain at the Hudson County Corrections and Rehabilitation Center, saw this first hand. For years Toro counseled his step-daughter’s brother, Carlos Rivera, as he struggled with heroin addiction. Rivera had found his brother dead from an overdose five years earlier, and he used heroin to deal with the pain, Toro said. And so when Rivera was at the Hudson County jail earlier this year on a robbery charge (he needed money for heroin, Toro said), Toro visited him in his unit, gave him books and crossword puzzles, and prayed with him.

“He would ask God to help him,” Toro said. “He would look for God.”

Then Rivera was released early as part of an effort in New Jersey to get hundreds out of jails to keep them safe from COVID. There was no advance warning before Rivera was released, and so Toro couldn’t arrange to send him to a treatment center in Puerto Rico, where most of Rivera’s family lives. Instead, Rivera found temporary shelter in the basement of a church in Elizabeth, where men released early from jail stayed on cots.

Soon enough, Rivera overdosed—twice. He was twice revived by another man living at the church.

One night in the spring Rivera was seen kneeling in prayer near his bed for an extended period of time. “So when they touched him: ‘Hey Carlos, how long are you going to be praying? He then just fell back. He was already gone,” Toro said. Rivera had overdosed a third time, and died.

After his death, the church closed its temporary shelter. So the men inside were left again to figure out how to face both their addictions, and the pandemic.

Newly discovered cells in mice can sense four of the five tastes

Taste buds can turn food from mere fuel into a memorable meal. Now researchers have discovered a set of supersensing cells in the taste buds of mice that can detect four of the five flavors that the buds recognize. Bitter, sweet, sour and umami — these cells can catch them all.

That’s a surprise because it’s commonly thought that taste cells are very specific, detecting just one or two flavors. Some known taste cells respond to only one compound, for instance, detecting sweet sucralose or bitter caffeine. But the new results suggest that a far more complicated process is at work.

When neurophysiologist Debarghya Dutta Banik and colleagues turned off the sensing abilities of more specific taste cells in mice, the researchers were startled to find other cells responding to flavors. Pulling those cells out of the rodents’ taste buds and giving them a taste of several compounds revealed a group of cells that can sense multiple chemicals across different taste classes, the team reports August 13 in PLOS Genetics.

“We never expected that any population of [taste] cells would respond to so many different compounds,” says Dutta Banik, of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

But taste cells don’t respond to flavors in insolation; the brain and the tongue work together as tastemakers (SN: 11/24/15). So the scientists monitored the brain to see if it received bitter, sweet or umami signals when mice lacked a key protein needed for these broadly tasting cells to relay information. Those observations revealed that without the protein, the brain didn’t get the flavor messages, which was also shown when mice slurped bitter solutions as though they were water even though the rodents hate bitter tastes, says Dutta Banik, who did the work at the University at Buffalo in New York.

While these broadly sensing cells were incommunicado, the also brain seemed to miss signals from other more specific taste cells, such as those for sensing bitterness. So it may be that the broadly sensing cells work with the others to communicate taste information.

“The presence of these [newly discovered] cells completely disrupts how people think the taste bud works,” says Kathryn Medler, a neurophysiologist at the University at Buffalo in New York.

Life without functioning taste cells would be beyond bland. Taste is crucial for survival, Medler says. When taste diminishes, with age or after treatments such as chemotherapy, people can lose their appetites and become malnourished. A working sense of taste also helps protect us from eating something spoiled or toxic.

Since taste works similarly in mice and humans, Medler says, untangling how such cells work may someday help scientists bring the flavor back for people who have lost the sense of taste.

“The long-term implications are pretty profound,” says Stephen Roper, a neurobiologist at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla., who was not involved with the work. Learning how these cells sense and how information passes between them, the buds and the brain, he says, could someday allow people to engineer taste signals.