Luis M. Tuesta, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, has been awarded the Avenir Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health, to study the epigenetic mechanisms of microglial activation and their role in shaping the behavioral course of opioid use disorder.

Author: bkellaway

Making Gyms Safer: Why the Virus Is Less Likely to Spread There Than in a Bar

After shutting down in the spring, America’s empty gyms are beckoning a cautious public back for a workout. To reassure wary customers, owners have put in place — and now advertise — a variety of coronavirus control measures. At the same time, the fitness industry is trying to rehabilitate itself by pushing back against what it sees as a misleading narrative that gyms have no place during a pandemic.

In the first months of the coronavirus outbreak, most public health leaders advised closing gyms, erring on the side of caution. As infections exploded across the country, states ordered gyms and fitness centers closed, along with restaurants, movie theaters and bars. State and local officials consistently branded gyms as high-risk venues for infection, akin to bars and nightclubs.

In early August, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo called gym-going a “dangerous activity,” saying he would keep them shut — only to announce later in the month that most gyms could reopen in September at a third of the capacity and under tight regulations.

New York, New Jersey and North Carolina were among the last state holdouts — only recently allowing fitness facilities to reopen. Many states continue to limit capacity and have instituted new requirements.

The benefits of gyms are clear. Regular exercise staves off depression and improves sleep, and staying fit may be a way to avoid a serious case of COVID-19. But there are clear risks, too: Lots of people moving around indoors, sharing equipment and air, and breathing heavily could be a recipe for easy viral spread. There are scattered reports of coronavirus cases traced back to specific gyms. But gym owners say those are outliers and argue the dominant portrayal overemphasizes potential dangers and ignores their brief but successful track record of safety during the pandemic.

A Seattle gym struggles to comply with new rules and survive

At NW Fitness in Seattle, everything from a set of squats to a run on the treadmill requires a mask. Every other cardio machine is off-limits. The owners have marked up the floor with blue tape to show where each person can work out.

Esmery Corniel, a member, has resumed his workout routine with the punching bag.

“I was honestly just losing my mind,” said Corniel, 27. He said he feels comfortable in the gym with its new safety protocols.

“Everybody wears their mask, everybody socially distances, so it’s no problem here at all,” Corniel said.

There’s no longer the usual morning “rush” of people working out before heading to their jobs.

Under Washington state’s coronavirus rules, only about 10 to 12 people at a time are permitted in this 4,000-square-foot gym.

“It’s drastically reduced our ability to serve our community,” said John Carrico. He and his wife, Jessica, purchased NW Fitness at the end of last year.

Meanwhile, the cost of running the businesses has gone up dramatically. The gym now needs to be staffed round-the-clock to keep up with the frequent cleaning requirements, and to ensure people are wearing masks and following the rules.

Keeping the gym open 24/7 — previously a big selling point for members — is no longer feasible. In the past three months, they’ve lost more than a third of their membership.

“If the trend continues, we won’t be able to stay open,” said Jessica Carrico, who also works as a nurse at a homeless shelter run by Harborview Medical Center.

Given her medical background, Jessica Carrico was initially inclined to trust the public health authorities who ordered all gyms to shut down, but gradually her feelings changed.

“Driving around the city, I’d still see lines outside of pot shops and Baskin-Robbins,” she said. “The arbitrary decision that had been made was very clear, and it became really frustrating.”

Even after gyms in the Seattle area were allowed to reopen, their frustrations continued — especially with the strict cap on operating capacity. The Carricos believe that falls hardest on smaller gyms that don’t have much square footage.

“People want this space to be safe, and will self-regulate,” said John Carrico. He believes he could responsibly operate with twice as many people inside as currently allowed. Public health officials have mischaracterized gyms, he added, and underestimated their potential to operate safely.

“There’s this fear-based propaganda that gyms are a cesspool of coronavirus, which is just super not true,” Carrico said.

Gyms seem less risky than bars. But there’s very little research either way

The fitness industry has begun to push back at the pandemic-driven perceptions and prohibitions. “We should not be lumped with bars and restaurants,” said Helen Durkin, an executive vice president for the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association (IHRSA).

John Carrico called the comparison with bars particularly unfair. “It’s almost laughable. I mean, it’s almost the exact opposite. … People here are investing in their health. They’re coming in, they’re focusing on what they’re trying to do as far as their workout. They’re not socializing, they’re not sitting at a table and laughing and drinking.”

Since the pandemic began, many gyms have overhauled operations and now look very different: Locker rooms are often closed and group classes halted. Many gyms check everyone for symptoms upon arrival. They’ve spaced out equipment and begun intensive cleaning regimes.

Gyms have a big advantage over other retail and entertainment venues, Durkin said, because the membership model means those who may have been exposed in an outbreak can be easily contacted.

A company that sells member databases and software to gyms has been compiling data during the pandemic. (The data, drawn from 2,877 gyms, is by no means comprehensive because it relies on gym owners to self-report incidents in which a positive coronavirus case was detected at the gym, or was somehow connected to the gym.) The resultant report said that the overall “visits to virus” ratio of 0.002% is “statistically irrelevant” because only 1,155 cases of coronavirus were reported among more than 49 million gym visits. Similarly, data collected from gyms in the United Kingdom found only 17 cases out of more than 8 million visits in the weeks after gyms reopened there.

Only a few U.S. states have publicly available information on outbreaks linked to the fitness sector, and those states report very few cases. In Louisiana, for example, the state has identified five clusters originating in “gym/fitness settings,” with a total of 31 cases. None of the people died. By contrast, 15 clusters were traced to “religious services/events,” sickening 78, and killing five of them.

“The whole idea that it’s a risky place to be … around the world, we just aren’t seeing those numbers anywhere,” said IHRSA’s Durkin.

A study from South Korea published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is often cited as evidence of the inherent hazards of group fitness activities.

The study traced 112 coronavirus infections to a Feb. 15 training workshop for fitness dance instructors. Those instructors went on to teach classes at 12 sports facilities in February and March, transmitting the virus to students in the dance classes, but also to co-workers and family members.

But defenders of the fitness industry point out that the outbreak began before South Korea instituted social distancing measures.

The study authors note that the classes were crowded and the pace of the dance workouts was fast, and conclude that “intense physical exercise in densely populated sports facilities could increase the risk for infection” and “should be minimized during outbreaks.” They also found that no transmission occurred in classes with fewer than five people, or when an infected instructor taught “lower-intensity” classes such as yoga and Pilates.

Public health experts continue to urge gym members to be cautious

It’s clear that there are many things gym owners — and gym members — can do to lower the risk of infection at a gym, but that doesn’t mean the risk is gone. Infectious disease doctors and public health experts caution that gyms should not downplay their potential for spreading disease, especially if the coronavirus is widespread in the surrounding community.

“There are very few [gyms] that can actually implement all the infection control measures,” said Saskia Popescu, an infectious disease epidemiologist in Phoenix. “That’s really the challenge with gyms: There is so much variety that it makes it hard to put them into a single box.”

Popescu and two colleagues developed a COVID-19 risk chart for various activities. Gyms were classified as “medium high,” on par with eating indoors at a restaurant or getting a haircut, but less risky than going to a bar or riding public transit.

Popescu acknowledges there’s not much recent evidence that gyms are major sources of infection, but that should not give people a false sense of assurance.

“The mistake would be to assume that there is no risk,” she said. “It’s just that a lot of the prevention strategies have been working, and when we start to loosen those, though, is where you’re more likely to see clusters occur.”

Any location that brings people together indoors increases the risk of contracting the coronavirus, and breathing heavily adds another element of risk. Interventions such as increasing the distance between cardio machines might help, but tiny infectious airborne particles can travel farther than 6 feet, Popescu said.

The mechanics of exercising also make it hard to ensure people comply with crucial preventive measures like wearing a mask.

“How effective are masks in that setting? Can they really be effectively worn?” asked Dr. Deverick Anderson, director of the Duke Center for Antimicrobial Stewardship and Infection Prevention. “The combination of sweat and exertion is one unique thing about the gym setting.”

“I do think that, in the big picture, gyms would be riskier than restaurants because of the type of activity and potential for interaction there,” Anderson said.

The primary way people could catch the virus at a gym would be coming close to someone who is releasing respiratory droplets and smaller airborne particles, called “aerosols,” when they breathe, talk or cough, said Dr. Dean Blumberg, chief of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health.

He’s less worried about people catching the virus from touching a barbell or riding a stationary bike that someone else used. That’s because scientists now think “surface” transmission isn’t driving infection as much as airborne droplets and particles.

“I’m not really worried about transmission that way,” Blumberg said. “There’s too much attention being paid to disinfecting surfaces and ‘deep cleaning,’ spraying things in the air. I think a lot of that’s just for show.”

Blumberg said he believes gyms can manage the risks better than many social settings like bars or informal gatherings.

“A gym where you can adequately social distance and you can limit the number of people there and force mask-wearing, that’s one of the safer activities,” he said.

Adapting to the pandemic’s prohibitions doesn’t come cheap

In Bellevue, Washington, PRO Club is an enormous, upscale gym with spacious workout rooms — and an array of medical services such as physical therapy, hormone treatments, skin care and counseling. PRO Club has managed to keep the gym experience relatively normal for members since reopening, according to employee Linda Rackner. “There is plenty of space for everyone. We are seeing about 1,000 people a day and have capacity for almost 3,000,” Rackner said. “We’d love to have more people in the club.”

The gym uses the same air-cleaning units as hospital ICUs, deploys ultraviolet robots to sanitize the rooms and requires temperature checks to enter. “I feel like we have good compliance,” said Dean Rogers, one of the personal trainers. “For the most part, people who come to a gym are in it for their own health, fitness and wellness.”

But Rogers knows this isn’t the norm everywhere. In fact, his own mother back in Oklahoma believes she contracted the coronavirus at her gym.

“I was upset to find out that her gym had no guidelines they were following, no safety precautions,” he said. “There are always going to be some bad actors.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes NPR and Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Carrie Feibel, an editor for the NPR-KHN reporting partnership, contributed to this story.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Kids Are Missing Critical Windows for Lead Testing Due to Pandemic

CLEVELAND — Families skipping or delaying pediatric appointments for their young children because of the pandemic are missing out on more than vaccines. Critical testing for lead poisoning has plummeted in many parts of the country.

In the Upper Midwest, Northeast and parts of the West Coast — areas with historically high rates of lead poisoning — the slide has been the most dramatic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In states such as Michigan, Ohio and Minnesota, testing for the brain-damaging heavy metal fell by 50% or more this spring compared with 2019, health officials report.

“The drop-off in April was massive,” said Thomas Largo, section manager of environmental health surveillance at the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, noting a 76% decrease in testing compared with the year before. “We weren’t quite prepared for that.”

Blood tests for lead, the only way to tell if a child has been exposed, are typically performed by pricking a finger or heel or tapping a vein at 1- and 2-year-old well-child visits. A blood test with elevated lead levels triggers the next critical steps in accessing early intervention for the behavioral, learning and health effects of lead poisoning and also identifying the source of the lead to prevent further harm.

Because of the pandemic, though, the drop in blood tests means referrals for critical home inspections plus medical and educational services are falling, too. And that means help isn’t reaching poisoned kids, a one-two punch, particularly in communities of color, said Yvonka Hall, a lead poisoning prevention advocate and co-founder of the Cleveland Lead Safe Network. And this all comes amid COVID-related school and child care closures, meaning kids who are at risk are spending more time than ever in the place where most exposure happens: the home.

“Inside is dangerous,” Hall said.

The CDC estimates about 500,000 U.S. children between ages 1 and 5 have been poisoned by lead, probably an underestimate due to the lack of widespread testing in many communities and states. In 2017, more than 40,000 children had elevated blood lead levels, defined as higher than 5 micrograms per deciliter of blood, in the 23 states that reported data.

While preliminary June and July data in some states indicates lead testing is picking up, it’s nowhere near as high as it would need to be to catch up on the kids who missed appointments in the spring at the height of lockdown orders, experts say. And that may mean some kids will never be tested.

“What I’m most worried about is that the kids who are not getting tested now are the most vulnerable — those are the kids I’m worried might not have a makeup visit,” said Stephanie Yendell, senior epidemiology supervisor in the health risk intervention unit at the Minnesota Department of Health.

Lifelong Consequences

There’s a critical window for conducting lead poisoning blood tests, timed to when children are crawling or toddling and tend to put their hands on floors, windowsills and door frames and possibly transfer tiny particles of lead-laden dust to their mouths.

Children at this age are more likely to be harmed because their rapidly growing brains and bodies absorb the element more readily. Lead poisoning can’t be reversed; children with lead poisoning are more likely to fall behind in school, end up in jail or suffer lifelong health problems such as kidney and heart disease.

That’s why lead tests are required at ages 1 and 2 for children receiving federal Medicaid benefits, the population most likely to be poisoned because of low-quality housing options. Tests are also recommended for all children living in high-risk ZIP codes with older housing stock and historically high levels of lead exposure.

Testing fell far short of recommendations in many parts of the country even before the pandemic, though, with one recent study estimating that in some states 80% of poisoned children are never identified. And when tests are required, there has been little enforcement of the rule.

Early in the pandemic, officials in New York’s Erie County bumped up the threshold for sending a public health worker into a family’s home to investigate the source of lead exposure from 5 micrograms per deciliter to 45 micrograms per deciliter (a blood lead level that usually requires hospitalization), said Dr. Gale Burstein, that county’s health commissioner. For all other cases during that period, officials inspected only the outside of the child’s home for potential hazards.

About 700 fewer children were tested for lead in Erie County in April than in the same month last year, a drop of about 35%.

Ohio, which has among the highest levels of lead poisoning in the country, recently expanded automatic eligibility for its Early Intervention program to any child with an elevated blood lead test, providing the opportunity for occupational, physical and speech therapy; learning supports for school; and developmental assessments. If kids with lead poisoning don’t get tested, though, they won’t be referred for help.

In early April, there were only three referrals for elevated lead levels in the state, which had been fielding nine times as many on average in the months before the pandemic, said Karen Mintzer, director of Bright Beginnings, which manages them for Ohio’s Department of Developmental Disabilities. “It basically was a complete stop,” she said. Since mid-June, referrals have recovered and are now above pre-pandemic levels.

“We should treat every child with lead poisoning as a medical emergency,” said John Belt, principal investigator for the Ohio Department of Health’s lead poisoning program. “Not identifying them is going to delay the available services, and in some cases lead to a cognitive deficit.”

Pandemic Compounds Worries

One of the big worries about the drop in lead testing is that it’s happening at a time when exposure to lead-laden paint chips, soil and dust in homes may be spiking because of stay-at-home orders during the pandemic.

Exposure to lead dust from deteriorating paint, particularly in high-friction areas such as doors and windows, is the most common cause of lead exposure for children in the U.S.

“I worry about kids in unsafe housing, more so during the pandemic, because they’re stuck there during the quarantine,” said Dr. Aparna Bole, a pediatrician at Cleveland’s University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

The pandemic may also compound exposure to lead, experts fear, as both landlords and homeowners try to tackle renovation projects without proper safety precautions while everyone is at home. Or the economic fallout of the crisis could mean some people can no longer afford to clean up known lead hazards at all.

“If you’ve lost your job, it’s going to make it difficult to get new windows, or even repaint,” said Yendell.

The CDC says it plans to help state and local health departments track down children who missed lead tests. Minnesota plans to identify pediatric clinics with particularly steep drops in lead testing to figure out why, said Yendell.

But, Yendell said, that will likely have to wait until the pandemic is over: “Right now I’m spending 10-20% of my time on lead, and the rest is COVID.”

The pandemic has stretched already thinly staffed local health departments to the brink, health officials say, and it may take years to know the full impact of the missed testing. For the kids who’ve been poisoned and had no intervention, the effects may not be obvious until they enter school and struggle to keep up.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

‘Terrible Role-Modeling’: California Lawmakers Flout Pandemic Etiquette

SACRAMENTO — In California, the cradle of renowned tech startups and the Silicon Valley, elementary school students have had to figure out how to work remotely, but lawmakers have not.

Since March, Californians have scrambled to comply with public health orders that required most office and school work to occur at home. But in one of the most iconic office spaces in the state — the Capitol building in Sacramento — most lawmakers and their staffers have gathered in large numbers for months (except when COVID-19 infections forced them to take unplanned recesses).

And as the end-of-session frenzy gripped them in late August, pandemic no-nos spiked: Lawmakers huddled closely, let their masks slip below their noses, smooshed together for photos and shouted “Aye!” and “No!” when voting in the Senate, potentially spraying virus-laden particles at their colleagues.

“It’s terrible role-modeling,” said Dr. Sadiya Khan, assistant professor of cardiology and epidemiology at Northwestern University. “Why do we have to do this if they’re not doing it?”

Legislative leaders are divided on whether remote voting violates the state constitution. Nonetheless, it was authorized — should it be needed — on a limited basis by both chambers in late July.

In the last week of the session, the Democratic leader of the state Senate ordered 10 Republican senators who lunched together to vote via video after one of them, Sen. Brian Jones (R-Santee), announced he had tested positive for the coronavirus. The lone Republican senator who did not dine with them was allowed to vote on the floor.

But the remote-voting option didn’t extend to others such as Assembly member Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland), who brought her newborn onto the floor for a late-night vote on Aug. 31.

.@BuffyWicks should’ve been home with her baby voting by proxy. That she came to #caleg is a testament to her but it didn’t have to be this way. Expecting + new moms can be “in the room where it happens” by being in the zoom where it happens. #WeSaidEnough https://t.co/Bh00nohICv

— Christine Pelosi (@sfpelosi) September 2, 2020

Lawmakers insist the guiding forces behind their decision-making have been “science-based protocols.”

But the science is pretty clear: Stay home, wear a mask that covers your nose and mouth, wash your hands and keep at least 6 feet away from people indoors. Maybe let your pregnant and nursing colleagues work from home.

Here at California Healthline, we let science and data guide our decisions, so we ran some of the legislators’ behavior by epidemiologists and infectious disease experts.

This isn’t (solely) to COVID-shame our elected officials for violating local, state and national recommendations governing how to conduct themselves in a pandemic — while crafting and debating the laws that govern our lives. Instead, we aim to be constructive. The pandemic rages on, and lawmakers may face similar conditions when they return in December to swear in newly elected members, or possibly sooner if Gov. Gavin Newsom calls for a special legislative session this fall.

Should Lawmakers Meet Indoors?

Health officials have pleaded with the public to stay home when possible to minimize the spread of COVID-19. The virus, they say, is extremely contagious, especially indoors.

But elected officials around the country continue to meet in person.

In California’s Capitol, everyone must wear masks, the number of visitors to the Assembly and Senate floors were limited to provide more social-distancing space among members, and plexiglass dividers were installed in both chambers.

“These are absolutely unprecedented times in the California State Senate, and there was no prior experience with live remote voting or participation,” Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins said in a statement to California Healthline. “So, we proceeded with a method that maximized participation while respecting public safety and meeting the legislature’s constitutional duties, which, as you know, private businesses do not have to consider in their remote decision making.”

Despite the precautions, congregating indoors is not wise, public health experts say.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea for any large group to have gathered, even if you were all wearing masks in an indoor environment,” Khan said.

“We know that wearing a mask — consistently and correctly — substantially reduces the risk of coronavirus spread but certainly does not eliminate it,” said Dr. Leana Wen, an emergency physician and visiting public health professor at George Washington University. “And in this time of a pandemic, we should all be doing what we can to switch to virtual meetings and gatherings, when possible.”

Broken Social-Distancing Rules

Time after time, California lawmakers flagrantly broke social-distancing rules.

Some didn’t wear masks that properly sealed their faces, or pulled their masks down to sip coffee. Impassioned senators yelled to cast votes, while their colleagues in the Assembly quietly voted at their desks by simply pushing a button. And lawmakers in both chambers huddled closely to confer.

“Physical distance is quite important, actually,” said Dr. George Rutherford, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California-San Francisco. It’s the “second layer” of protection after masks, he said.

“I realize it doesn’t lend itself well to this kind of business, but you have to figure it out,” he said.

Thank you Majority Leader @IanCalderon for your incredible service to our legislature & all Californians! You’ll be dearly missed but you’ve earned some well deserved quality time with your family. I know we’ll see you in service again. Until then, wish you nothing but happiness! pic.twitter.com/phXFcXVPKf

— Ash Kalra 🌱 (@Ash_Kalra) September 2, 2020

Lawmakers, Rutherford noted, are prone to dramatic speeches and like to yell passionately into microphones to make a point, which is not particularly good behavior under COVID.

“I mean, the louder you talk, the greater your exhalational force, the more likely you are to overwhelm the protections of the mask,” he said.

The Cry Heard ’Round the World

A baby’s cry from the Assembly floor triggered national rebuke of California’s legislature. When Wicks came to the floor to vote on a housing bill Aug. 31, her month-old daughter, Elly, wasn’t pleased that her late-night feeding had been interrupted.

And Elly agrees! #CALeg https://t.co/U3E1KIChmA pic.twitter.com/ETodCXCjv3

— M Franco (@rjactivista) September 1, 2020

Wicks had asked Assembly leadership if she could vote by proxy but was told she was not at high risk for COVID-19. Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon later apologized.

“Inclusivity and electing more women into politics are core elements of our Democratic values,” Rendon said in a statement. “Nevertheless, I failed to make sure our process took into account the unique needs of our Members. The Assembly needs to do better. I commit to doing better.”

The photo of Wicks holding her swaddled baby in her arms went viral — a rallying cry for mothers across the country balancing the demands of work with children at home. Plus, requiring that she appear in person was not only unnecessary, Wen said, but dangerous.

“Newborns are extremely high-risk because they have no immunity, other than the immunity that they obtained from their mother, said Wen, who is the mother of a 5-month-old. “Every employer, every entity needs to do everything they can to be flexible during this time of a pandemic.”

Why Not Legislate Virtually?

Congress continues to gavel into session in person, and many state constitutions require legislatures to meet in person. At least 30 states have allowed remote voting, extended bill deadlines or made other legislative accommodations since the start of the pandemic, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Only Wisconsin and Oregon already had rules in place for remote voting in case of an emergency.

California dabbled with online hearings this spring and summer and witnesses testified remotely. There were the usual trip-ups: mute buttons still engaged, a crackly phone line or a lawmaker caught uttering a bad word.

This moment says everything about 2020. State Sen. @ScottWilkCA, struggling with mute on his Zoom voting in Senate session, looked to have mouthed one of those not-so-nice words in frustration. The chamber laughed and his face was priceless.

Senator, thanks for this moment! pic.twitter.com/2yphFgOp3M

— John Myers (@johnmyers) August 28, 2020

But the technology is available to conduct the people’s business, and public health experts urged lawmakers to consider updating their rules.

“It’s not the same as being in person for sure. It is really hard to accomplish things the same way,” Khan acknowledged. But “in 2020, we’re very blessed with a million different ways to remotely interact for video and audio that should be explored and exhausted before saying that there is no better option.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KHN’s ‘What the Health?’: The Politics of Science

Can’t see the audio player? Click here to listen on SoundCloud.

The headlines from this week will be about how President Donald Trump knew early on how serious the coronavirus pandemic was likely to become but purposely played it down. Potentially more important during the past few weeks, though, are reports of how White House officials have pushed scientists at the federal government’s leading health agencies to put politics above science.

Meanwhile, Republicans appear to have given up on using the Affordable Care Act as an electoral cudgel, judging, at least, from its scarce mention during the GOP convention. Democrats, on the other hand, particularly those running for the U.S. House and Senate, are doubling down on their criticism of Republicans for failing to adequately protect people with preexisting health conditions. That issue was key to the party winning back the House in 2018.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of Kaiser Health News, Joanne Kenen of Politico, Mary Ellen McIntire of CQ Roll Call and Sarah Karlin-Smith of the Pink Sheet.

Among the takeaways from this week’s podcast:

- The Affordable Care Act has become a political vulnerability for Republican officials, who have no interest in reopening the debate on it during this campaign. Trump vowed before his 2016 election to repeal the law immediately after taking office and members of Congress had berated it for years. But they could not gain the political capital to overturn Obamacare.

- Trump’s comments to journalist-author Bob Woodward about holding back information on the risks of the coronavirus pandemic from the public may not have a major effect on the election since so many voters’ minds are already set on their choices. For many, the president’s statements are seen by partisans as identifying what they already believe: for Trump’s supporters, that he is protecting the public; for his critics, that he is a liar.

- The number of COVID-19 cases appears to have hit another plateau, but it’s still twice as high as the count last spring. Officials are waiting to see if end-of-the-summer activities over the Labor Day holiday will create another surge.

- The stalemate on Capitol Hill over coronavirus relief funding shows no sign of easing soon. Republicans in the Senate are resisting Democrats’ insistence on a massive package, but it’s not exactly clear what the GOP can agree on.

- The vaccine being developed by AstraZeneca ran into difficulty this week as experts seek to determine whether a neurological problem that developed in one volunteer was caused by the vaccine. Some public health officials, such as NIH Director Francis Collins, said this helps show that even with the compressed testing timeline, safeguards are working.

- Nonetheless, another vaccine maker, Pfizer, said it might still have its vaccine ready before the election.

- The recent controversy at the FDA over the emergency authorization of plasma to treat COVID patients and the awkward decision at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to change guidelines for testing asymptomatic people have created a credibility gap among some Americans and played into concerns that the administration is undercutting science.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KHN’s Elizabeth Lawrence, who reported the August NPR-KHN “Bill of the Month” installment, about an appendectomy gone wrong, and the very big bill that followed. If you have an outrageous medical bill you would like to share with us, you can do that here.

Plus, for extra credit, the panelists recommend their favorite health policy stories of the week they think you should read too:

Julie Rovner: ProPublica’s “A Doctor Went to His Own Employer for a COVID-19 Antibody Test. It Cost $10,984,” by Marshall Allen

Joanne Kenen: The Atlantic’s “America Is Trapped in a Pandemic Spiral,” by Ed Yong

Sarah Karlin-Smith: Politico’s “Emails Show HHS Official Trying to Muzzle Fauci,” by Sarah Owermohle

Mary Ellen McIntire: The Atlantic’s “What Young, Healthy People Have to Fear From COVID-19,” by Derek Thompson

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to What the Health? on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, Spotify, or Pocket Casts.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

Dark matter clumps in galaxy clusters bend light surprisingly well

Dark matter just got even more puzzling.

This unidentified stuff, which makes up most of the mass in the cosmos, is invisible but detectable by the way it gravitationally tugs on objects like stars. (SN: 11/25/19). Dark matter’s gravity can also bend light traveling from distant galaxies to Earth — but now some of this mysterious substance appears to be bending light more than it’s supposed to. A surprising number of dark matter clumps in distant clusters of galaxies severely warp background light from other objects, researchers report in the Sept. 11 Science.

This finding suggests that these clumps of dark matter, in which individual galaxies are embedded, are denser than expected. And that could mean one of two things: Either the computer simulations that researchers use to predict galaxy cluster behavior are wrong, or cosmologists’ understanding of dark matter is.

Very high concentrations of dark matter can act like a lens to bend light and drastically alter the appearance of background galaxies as seen from Earth — stretching them into arcs or splitting them into multiple images of the same object on the sky. “It’s totally cool. It’s like a fun house mirror,” says astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan of Yale University.

Judging by computer simulations of galaxy clusters, clumps of dark matter around individual galaxies that are dense enough to cause such dramatic gravitational lensing effects should be rare (SN: 10/4/15). Based on cluster simulations run by Natarajan and colleagues, “we would expect to see 1 [strong lensing] event in every 10 clusters or so,” says study coauthor Massimo Meneghetti, an astrophysicist at the Astrophysics and Space Science Observatory of Bologna in Italy.

But telescope images told a different story. The researchers used observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope in Chile to investigate 11 galaxy clusters from about 2.8 billion to 5.6 billion light-years away. In that set, the team identified 13 cases of severe gravitational lensing by dark matter clumps around individual galaxies. These observations indicate there are more high-density dark matter clumps in real galaxy clusters than in simulated ones, Meneghetti says.

The simulations could be missing some physics that leads dark matter in galaxy clusters to glom tightly together, Natarajan says. “Or … there’s something fundamentally off about our assumptions about the nature of dark matter,” she says, like the notion that gravity is the only attractive force that dark matter feels.

Richard Ellis, a cosmologist at the University College London who was not involved in the work, thinks the crux of the problem is more likely in the computer simulations than in the nature of dark matter. “A cluster of galaxies is a very dangerous place. It’s like the Manhattan of the universe,” he says — busy with galaxies whizzing past one another, colliding and getting torn up. “There’s awful physics that goes into predicting how many of these little lensed things they should find,” Ellis says, so the new result “is intriguing, but my suspicion is that there’s something in the simulations … that isn’t quite right.”

Future observations with the upcoming Euclid space telescope (SN: 11/14/17), the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (SN: 1/10/20) could help clear matters up, says Bhuvnesh Jain, an astrophysicist at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in the work. “These three telescopes are going to produce extremely large samples of galaxy clusters,” he says. That may lead to a new understanding of the physics in these turbulent environments, and help determine whether unrealistic simulations are to blame for this dark matter mystery.

Hazelden Betty Ford CEO to be Stepping Away

Addiction Recovery Bulletin

Passing the First Lady’s baton –

September 9, 2020 – Mishek, the third-longest-serving leader in the organization’s 71-year history and architect of the historic 2014 merger of the Hazelden Foundation and the Betty Ford Center, says he will step down when his successor is hired—likely in the first half of next year. Until then, he will continue to lead the addiction treatment leader through the pandemic, which has increased demand for Hazelden Betty Ford’s services, and advance the innovation, collaboration and growth that have defined his tenure.

“While I’m excited about the next chapter in my life, I’m equally excited about the future of Hazelden Betty Ford and know that our mission is more important than ever before,” Mishek said. “In this extraordinary time, I remain 100% focused on our employees, the people we serve, and the hope and healing that so many individuals, families and communities need right now.”

When Mishek assumed leadership of the Hazelden Foundation in 2008, the Center City, Minnesota-headquartered nonprofit had six sites nationwide. Today, after several acquisitions and start-ups, as well as the pivotal merger with the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, California, the new Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation has 17 sites and is on its way to offering virtual care in all 50 states through its industry-leading RecoveryGo behavioral health service. Major construction projects are also under way and planned to enhance and expand the organization’s two largest campuses in Center City and Rancho Mirage. In addition, the organization is serving a growing number of people nationally through its graduate school of addiction studies, publishing division, research center, professional and medical education branch, school- and community-based prevention programs and public advocacy arm.

During Mishek’s tenure—a period marked by seismic shifts in healthcare…

more@HazeldenBettyFord

The post Hazelden Betty Ford CEO to be Stepping Away appeared first on Addiction/Recovery eBulletin.

How does a crop’s environment shape a food’s smell and taste?

About seven years ago, Kristin and Josh Mohagen were honeymooning in Napa Valley in California, when they smelled something surprising in their glasses of Cabernet Sauvignon: green pepper. A vintner explained that the grapes in that bottle had ripened on a hillside alongside a field of green peppers. “That was my first experience with terroir,” Josh Mohagen says.

It made an impression. Inspired by their time in Napa, the Mohagens returned home to Fergus Falls, Minn., and launched a chocolate business based on the principle of terroir, often defined as “sense of place.”

Different countries produce cocoa with distinct flavors and aromas, Kristin Mohagen says. Cocoa from Madagascar “has a really bright berry flavor, maybe raspberry, maybe citrus,” she says, while cocoa from the Dominican Republic “has a little more nutty, chocolaty taste.”

The couple estimates that back in 2013, when they founded Terroir Chocolate, about 50 other small batch chocolate companies in the United States were also touting terroir as integral to their products’ flavors.

Since then, terroir has continued to take hold as a marketing strategy — and not just for wine and chocolate. Terroir labels are also becoming more common for products like coffee, tea and craft beer, says Miguel Gómez, an economist at Cornell University who studies food marketing and distribution. Consumers “are increasingly interested in knowing where the products they are eating are produced — not only where but who is making them and how,” he says. People “value differences in the aromas, the flavors.”

The definition of terroir is somewhat fluid. Wine enthusiasts use the French term to describe the environmental conditions in which a grape is grown that give a wine its unique flavor. The soil, climate and even the orientation of a hillside or the company of neighboring plants, insects and microbes play a role. Some experts expand terroir to include specific cultural practices for growing and processing grapes that could also influence flavor.

The notion of terroir is quite old. In the Middle Ages, Cistercian and Benedictine monks in Burgundy, France, divided the countryside into climats, according to subtle differences in the landscape that seemed to translate into unique wine characteristics. Wines produced around the village of Gevrey-Chambertin, for example, “are famous for being fuller-bodied, powerful and more tannic than most,” says sommelier Joe Quinn, wine director of The Red Hen, a restaurant in Washington, D.C. “In contrast, the wines from the village of Chambolle-Musigny, just a few miles south, are widely considered to be more fine, delicate and light-bodied.”

Some scientists and wine experts are skeptical that place actually leaves a lasting imprint on taste. But a recent wave of scientific research suggests that the environment and production practices can, in fact, impart a chemical or microbial signature so distinctive that scientists can use the signature to trace food back to its origin. And in some cases, these techniques are beginning to offer clues on how terroir can shape the aroma and flavor of food and drink.

Coffee’s chemical fingerprint

Ecologist Jim Ehleringer of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City studies trace elements that plants passively take up. Those elements are a direct reflection of the soil. “Trace elements do not decay and so they become characteristic of a soil type and persist over time,” Ehleringer says.

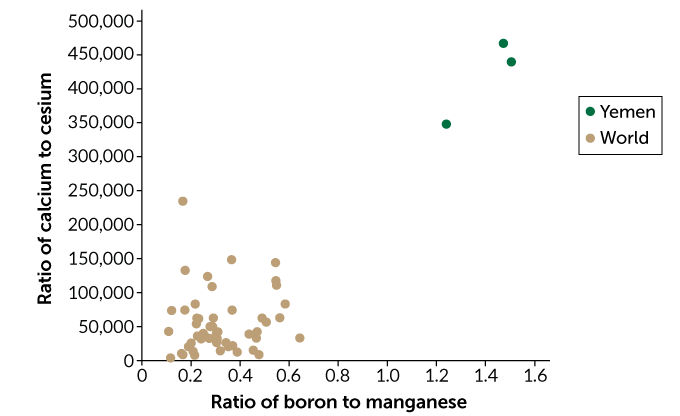

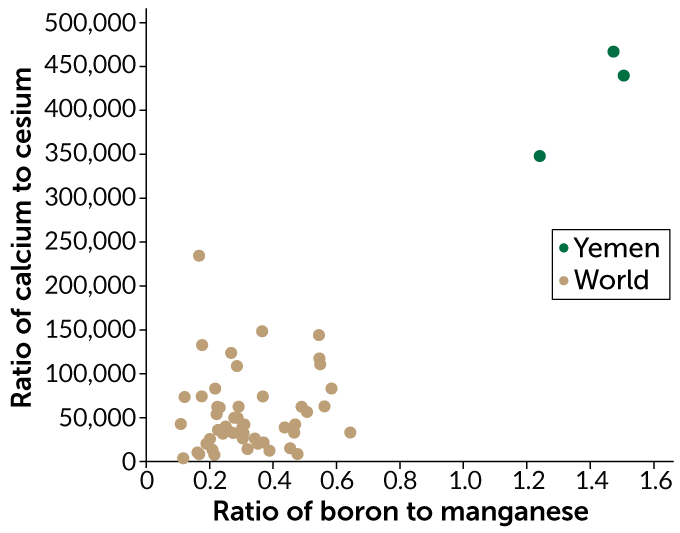

To see if they could trace a coffee to its origin using the coffee’s blend of trace elements, Ehleringer and his team recently measured the concentrations of about 40 trace elements in more than four dozen samples of roasted arabica coffee beans from 21 countries. Roasting beans to different temperatures can affect the concentrations of individual elements. To correct for this roasting effect, Ehleringer calculated the ratio of each element to every other element in a sample, which remains fairly constant, even with roasting.

In the Aug. 1 issue of Food Chemistry, his team reports that coffee beans from different regions can have distinct chemical fingerprints. A coffee’s chemical quality “comes down to geology,” Ehleringer says. Three samples of coffee beans from Yemen, for example, had a ratio of boron to manganese that was shared by less than 0.5 percent of coffee samples grown elsewhere.

Other researchers have used similar elemental analyses to find chemical signatures of place in products ranging from wines produced in distinct growing regions in Portugal to peanuts grown in different provinces in China.

The technique is valuable for validating origin when terroir is part of a product’s allure. Coffee farmers in Kona on Hawaii’s Big Island, for example, are using the results of an elemental analysis to support a class action lawsuit, scheduled for trial in November, against 21 major retailers. The suit claims those companies falsely market their coffees as “Kona” when the beans were actually grown elsewhere.

While an elemental analysis can authenticate a product’s terroir, it does not suggest that geology shapes flavor. Trace elements alone, says Ehleringer, “impart no flavor or taste.”

Tracking cocoa to its source

To try to link flavor to place, some scientists go after different chemical signatures altogether. At Towson University in Maryland, chemist Shannon Stitzel is tracing cocoa to its roots using organic compounds, which are mostly produced by the cocoa plant itself. The concentration of specific organic compounds in a plant can result from a complex mix of interacting factors — from the genes of a particular variety to components of terroir like climate and agricultural practices.

Stitzel works with samples of cocoa liquor — cocoa beans that have been fermented, dried, roasted and ground into a paste — from across the globe. At room temperature, cocoa liquor is a solid. But with a bit of heat, the paste melts into a glossy liquid that Stitzel describes as “a little thicker than honey.”

Using organic compounds to assign the cocoa liquor samples to their countries of origin is “not nearly as clean as when you do it with elemental analysis,” she says. In unpublished work, she was able to use an elemental analysis to accurately link cocoa liquor to its country of origin about 97 percent of the time.

But Stitzel turned to organic compounds because their presence may ultimately help explain the flavor differences that she, like the Mohagens, thinks very clearly exist between cocoa liquors from different countries. “You can open up each of the containers and the aroma is entirely different,” she says.

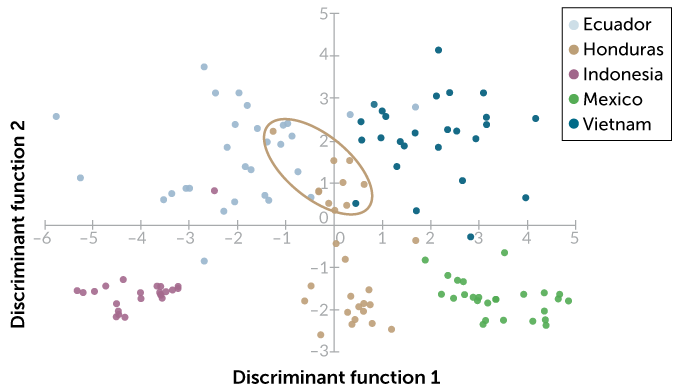

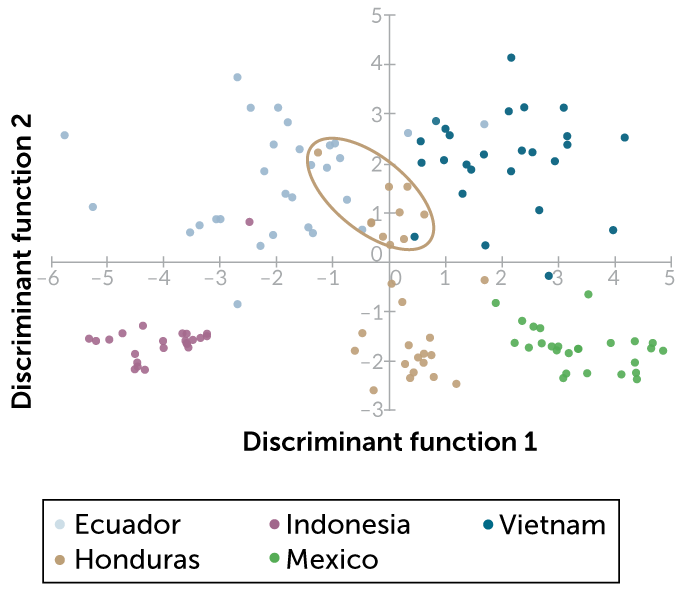

Stitzel recently identified concentrations of organic compounds in cocoa liquor from Vietnam, Indonesia, Honduras, Ecuador and Mexico. She then used a statistical technique known as a discriminant analysis to group samples based on similar concentrations of nine organic compounds, including caffeine, a similar compound called theobromine and an antioxidant called epicatechin.

On the American Chemical Society’s SciMeetings online platform in April, Stitzel reported that this chemical fingerprint was enough to accurately identify the correct country of origin for about 90 percent of the samples. In some cases, however, the samples didn’t form neat groups by country. Cocoa liquor samples from Honduras formed two different groups, depending on roasting temperature. Samples in the Honduras group that were roasted at the highest temperature were hard to tell apart from samples from Ecuador and Vietnam.

Stitzel now wants to add more compounds to the analysis to boost her sourcing accuracy and to connect regions to specific flavor compounds. “We’re still … trying to understand which compounds might be related to flavor,” she says. Her recent analysis already shows that caffeine, theobromine and epicatechin, which all produce a bitter flavor, can help set apart one country’s chocolates from another’s.

The aroma of place

Other researchers are finding that terroir leaves an imprint on the molecules that shape food’s aroma. Plants produce compounds known as aroma glycosides, which contain a sugar component linked to a volatile aromatic compound. When intact, aroma glycosides have no scent. But breaking the sugar-volatile bond — via high temperatures, low pH or enzymes from yeast — sets the volatile and its aroma free. The bouquet of a nicely aged bottle of wine is made up, in part, of aroma volatiles in the grapes that yeast enzymes let loose over time.

Many beer brewers, however, would rather your IPA have the same reliable flavor whether you pop open the bottle this Friday or in October. When volatile aromatics let loose in a bottled beer, that’s no good for large-volume brewers who need to ship consistent-tasting products. Brewers call that volatile release “beer creep,” says Paul Matthews, a senior research scientist in the Washington state branch of Hopsteiner, an international commercial hop grower and processor headquartered in New York City.

If brewers add hops (the flower of the hop plant) to beer early in the brewing cycle, heat breaks the sugar-volatile bond and the aroma from aroma glycosides is largely lost before bottling. The remaining flavor is more consistent over time. But when craft brewers make “dry hopped” beers like IPAs, adding the hops after the boiling stage, this late addition allows many aroma glycosides to go into fermentation and then into the bottle intact. The compounds release volatile aromatics as yeast enzymes break bonds even after the bottle is capped. So the aromas of these beers are more likely to “creep” over time.

Because genetics influences aroma and flavor, Matthews is exploring whether it’s possible to better control aroma glycoside concentrations through breeding. Breeding hop varieties to have lower concentrations could diminish the “beer creep” problem faced by large-volume craft brewers who distribute their beer over long distances.

At the same time, Matthews and colleagues are investigating the potential of breeding hop varieties to have higher aroma glycoside concentrations for use by smaller craft brewers, who are less concerned about shelf life but want to enhance the aroma of their beers.

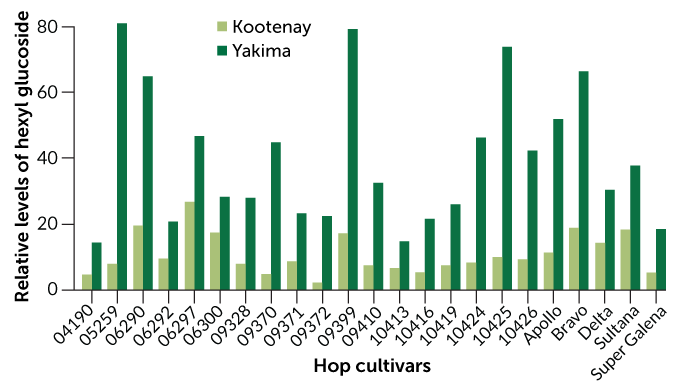

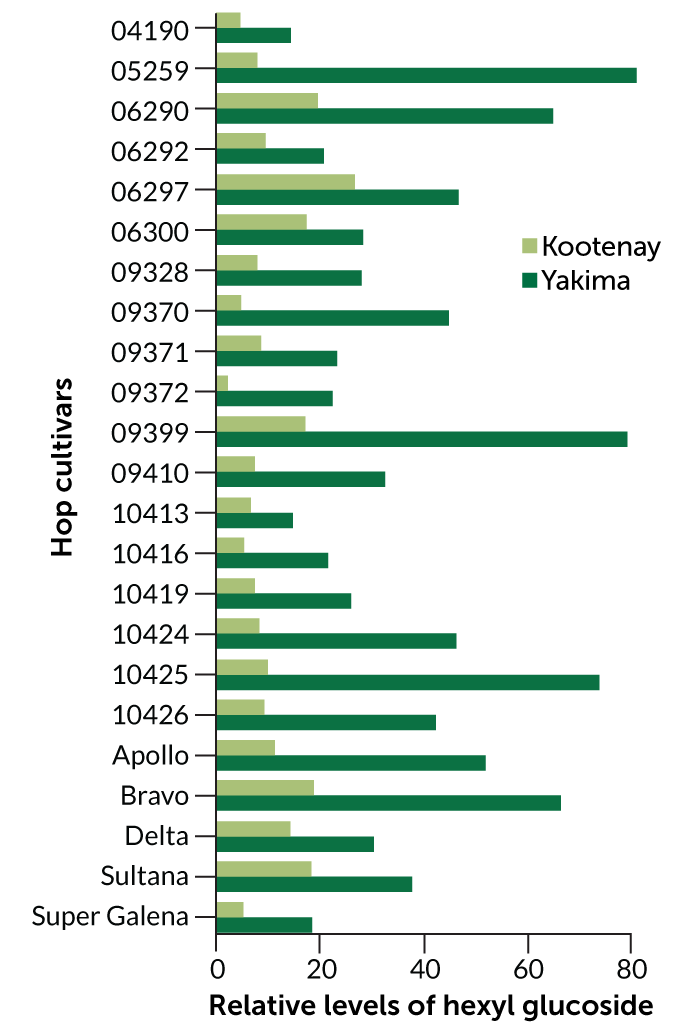

Matthews recently tested whether aroma glycoside concentrations in individual hop cultivars are determined more by genetics or by terroir. “Of course, they are determined by both,” he says. “But if they are more genetic, we can breed for them.”

In collaboration with colleagues, including phytochemist Taylan Morcol of Lehman College in the Bronx, part of the City University of New York, Matthews grew the same 23 genetically distinct hop cultivars at two commercial fields with distinct terroirs. Matthews calls the Yakima Valley site in Washington state “desert in the shadow of Mount Rainier.” The other site, in the Kootenay River valley in Idaho, is “much more boreal — pine forest and humid,” he says.

At each location, the team measured the concentrations of four aroma glycosides in each hop cultivar. Genetics indeed played the biggest role in determining how much aroma glycosides a hop plant produces, the researchers report in the Aug. 15 Food Chemistry. The concentrations of three of the aroma glycosides differed across cultivar types but remained fairly similar within the same cultivar grown in the two locations.

But for one aroma glycoside, terroir trumped genes in a big way. At the Kootenay site, all of the cultivars produced low concentrations of hexyl glucoside, a molecule that gives off a grassy aroma when its sugar bond is broken. But at the Yakima site, every one of these same cultivars, with genetics matching the plants in Kootenay, produced about two to eight times as much hexyl glucoside.

“There is a terroir difference,” Matthews says. The team can’t yet pinpoint which component of terroir causes the spike in hexyl glucoside at the Yakima site. The best guess: mites and aphids.

At Yakima, those critters, which munch on the hop plants, hang around for a longer portion of the growing season than at the Kootenay site. Matthews and his colleagues hypothesize that the plants might produce hexyl glucoside chemicals as a defense against the pests. When a mite or aphid munches on the plant, the volatile may be released to attract insects that will eat the mites or aphids.

The researchers are planning a follow-up experiment to test whether hop plants exposed to these pests in environmentally controlled chambers produce more of this grassy hexyl glucoside than hop grown under the same environmentally controlled conditions without the pests.

Microbes leave their mark

People have understood the importance of yeast in wine fermentation for at least two centuries. About six years ago, food microbiologist David Mills of the University of California, Davis and graduate student Nicholas Bokulich, now a food microbiologist at ETH Zurich, discovered that groups of microbes may help shape the flavor of wine. Unique microbial communities in different California growing regions can predict which metabolites will be present in the finished wine, Mills, Bokulich and colleagues reported in 2016 in mBio. “Metabolites are any product of metabolism in any organism,” Bokulich says, adding that yeast, other fungi and bacteria each make varying contributions of metabolites in different wines.

“Those metabolites … have an aroma and a flavor,” says Kate Howell, a biochemist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. One of Howell’s own studies, she and her team reported online in August in mSphere, suggests that fungal species in particular shape the metabolites — and thus aroma and flavor — in wine from different growing regions in Australia.

Howell and colleagues studied microbes at 15 vineyards growing Pinot Noir grapes across six wine regions in southern Australia. At each vineyard, the team extracted fungal and bacterial DNA from the soil, as well as from what’s known as the “must” — destemmed, crushed grapes that haven’t yet been fermented. Then, the team identified 88 metabolites in the finished wine.

Different wine growing regions had distinct microbial communities in both the soil and the must, which appeared to influence the unique compositions of metabolites in the finished wine. The researchers found that over 80 percent of the metabolites found in the various wines were linked to the diversity of fungi found in the grape must. High levels of Penicillium fungi, for example, resulted in wine with low levels of octanoic acid, a volatile compound that can give wine a mushroom flavor.

Howell hopes vintners may someday be able to manage microbes in the soil and throughout the fermentation process to bring out the best of the local microbial terroir. Today, nearly all of the yeasts that vintners purchase to add to their grape must are isolated from French vineyards and other famous wine regions, she says. “That doesn’t present the same value of place as encouraging diversity in the fermentation in the place that the grapes were grown.”

For his part, Quinn, of The Red Hen, eagerly awaits more scientific explorations of terroir. He would especially like to know why wines produced from the limestone-dominated Kimmeridgian soils in Chablis, Sancerre and Champagne, France, all have a chalky, saltlike mineral taste. Scientific research helps explain how wine reflects its place, Quinn says, “from the climatic elements to the microbial elements, what the earth is saying, and why [a particular] wine is so delicious.”

Hospitals, Nursing Homes Fail to Separate COVID Patients, Putting Others at Risk

Nurses at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center were on edge as early as March when patients with COVID-19 began to show up in areas of the hospital that were not set aside to care for them.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had advised hospitals to isolate COVID patients to limit staff exposure and help conserve high-level personal protective equipment that’s been in short supply.

Yet COVID patients continued to be scattered through the Oakland hospital, according to complaints to California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health. The concerns included the sixth-floor medical unit where veteran nurse Janine Paiste-Ponder worked.

COVID patients on that floor were not staying in their rooms, either confused or uninterested in the rules. Staff was not provided highly protective N95 respirators, said Mike Hill, a nurse in the hospital intensive care unit and the hospital’s chief representative for the California Nurses Association, which filed complaints to Cal/OSHA, the state’s workplace safety regulator.

“It was just a matter of time before one of the nurses died on one of these floors,” Hill said.

Two nurses fell ill, including Paiste-Ponder, 59, who died of complications from the virus on July 17.

The concerns raised in Oakland also have swept across the U.S., according to interviews, a review of government workplace safety complaints and health facility inspection reports. A KHN investigation found that dozens of nursing homes and hospitals ignored official guidelines to separate COVID patients from those without the coronavirus, in some places fueling its spread and leaving staff unprepared and infected or, in some cases, dead.

As recently as July, a National Nurses United survey of more than 21,000 nurses found that 32% work in a facility that does not have a dedicated COVID unit. At that time, the coronavirus had reached all but 17 U.S. counties, data collected by Johns Hopkins University shows.

KHN discovered that COVID victims have been commingled with uninfected patients in health care facilities in states including California, Florida, New Jersey, Iowa, Ohio, Maryland and New York.

A COVID-19 outbreak was in full swing at the New Jersey Veterans Home at Paramus in late April when health inspectors observed residents with dementia mingling in a day room — COVID-positive patients as well as others awaiting test results. At the time, the center had already reported COVID infections among 119 residents and 46 virus-related deaths, according to a Medicare inspection report.

The assistant director of nursing at an Iowa nursing home insisted April 28 that they did “not have any COVID in the building” and overrode the orders of a community doctor to isolate several patients with fevers and falling oxygen levels, an inspection report shows.

By mid-May, the facility’s COVID log showed 61 patients with the virus and nine dead.

Federal work-safety officials have closed at least 30 complaints about patient mixing in hospitals nationwide without issuing a citation. They include a claim that a Michigan hospital kept patients who tested negative for the virus in the COVID unit in May. An upstate New York hospital also had COVID patients in the same unit as those with no infection, according to a closed complaint to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Federal Health and Human Services officials have called on hospitals to tell them each day if they have a patient who came in without COVID-19 but had an apparent or confirmed case of the coronavirus 14 days later. Hospitals filed 48,000 reports from June 21 through Aug. 28, though the number reflects some double or additional counting of individual patients.

COVID patients have been mixed in with others for a variety of reasons. Some hospitals report having limited tests, so patients carrying the virus are identified only after they had already exposed others. In other cases, they had false-negative test results or their facility was dismissive of federal guidelines, which carry no force of law.

And while federal Medicare officials have inspected nearly every U.S. nursing home in recent months and states have occasionally levied fines and cut off new admissions for isolation lapses, hospitals have seen less scrutiny.

The Scene Inside Sutter

At Alta Bates in Oakland, part of the Sutter Health network, hospital staff made it clear in official complaints to Cal/OSHA that they wanted administrators to follow the state’s unique law on aerosol-transmitted diseases. From the start, some staffers wanted all the state-required protections for a virus that has been increasingly shown to be transmitted by tiny particles that float through the air.

The regulations call for patients with a virus like COVID-19 to be moved to a specialized unit within five hours of identification — or to a specialized facility. The rules say those patients should be in a room with a HEPA filter or with negative air pressure, meaning that air is circulated out a window or exhaust fan instead of drifting into the hallway.

Initially, in March, the hospital outfitted a 40-bed COVID unit, according to Hill. But when a surge of patients failed to materialize, that unit was pared to 12 beds.

Since then, a steady stream of virus patients have been admitted, he said, many testing positive only days after admission — and after they’d been in regular rooms in the facility.

From March 10 through July 30, Hill’s union and others filed eight complaints to Cal/OSHA, including allegations that the hospital failed to follow isolation rules for COVID patients, some on the cancer floor.

So far, regulators have done little. Gov. Gavin Newsom had ordered workplace safety officials to “focus on … supporting compliance” instead of enforcement except on the “most serious violations.”

State officials responded to complaints by reaching out by mail and phone to “ensure the proper virus prevention measures are in place,” according to Frank Polizzi, a spokesperson for Cal/OSHA.

A third investigation related to transport workers not wearing N95 respirators while moving COVID-positive or possible coronavirus patients at a Sutter facility near the hospital resulted in a $6,750 fine, Cal/OSHA records show.

The string of complaints also says the hospital did not give staff the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) under state law — an N95 respirator or something more protective — for caring for virus patients.

Instead, Hill said, staff on floors with COVID patients were provided lower-quality surgical masks, a concern reflected in complaints filed with Cal/OSHA.

Hill believes that Paiste-Ponder and another nurse on her floor caught the virus from COVID patients who did not remain in their rooms.

“It is sad, because it didn’t really need to happen,” Hill said.

Polizzi said investigations into the July 17 death and another staff hospitalization are ongoing.

A Sutter Health spokesperson said the hospital takes allegations, including Cal/OSHA complaints, seriously and its highest priority is keeping patients and staff safe.

The statement also said “cohorting,” or the practice of grouping virus patients together, is a tool that “must be considered in a greater context, including patient acuity, hospital census and other environmental factors.”

Concerns at Other Hospitals

CDC guidelines are not strict on the topic of keeping COVID patients sectioned off, noting that “facilities could consider designating entire units within the facility, with dedicated [staff],” to care for COVID patients.

That approach succeeded at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. A recent study reported “extensive” viral contamination around COVID patients there, but noted that with “standard” infection control techniques in place, staffers who cared for COVID patients did not get the virus.

The hospital set up an isolation unit with air pumped away from the halls, restricted access to the unit and trained staff to use well-developed protocols and N95 respirators — at a minimum. What worked in Nebraska, though, is far from standard elsewhere.

Cynthia Butler, a nurse and National Nurses United member at Fawcett Memorial Hospital in Port Charlotte, on Florida’s west coast, said she actually felt safer working in the COVID unit — where she knew what she was dealing with and had full PPE — than on a general medical floor.

She believes she caught the virus from a patient who had COVID-19 but was housed on a general floor in May. A similar situation occurred in July, when another patient had an unexpected case of COVID — and Butler said she got another positive test herself.

She said both patients did not meet the hospital’s criteria for testing admitted patients, and the lapses leave her on edge, concerns she relayed to an OSHA inspector who reached out to her about a complaint her union filed about the facility.

“Every time I go into work it’s like playing Russian roulette,” Butler said.

A spokesperson for HCA Healthcare, which owns the hospital, said it tests patients coming from long-term care, those going into surgery and those with virus symptoms. She said staffers have access to PPE and practice vigilant sanitation, universal masking and social distancing.

The latter is not an option for Butler, though, who said she cleans, feeds and starts IVs for patients and offers reassurance when they are isolated from family.

“I’m giving them the only comfort or kind word they can get,” said Butler, who has since gone on unpaid leave over safety concerns. “I’m in there doing that and I’m not being protected.”

Given research showing that up to 45% of COVID patients are asymptomatic, UCSF Medical Center is testing everyone who’s admitted, said Dr. Robert Harrison, a University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine professor who consults on occupational health at the hospital.

It’s done for the safety of staff and to reduce spread within the hospital, he said. Those who test positive are separated into a COVID-only unit.

And staff who spent more than 15 minutes within 6 feet of a not-yet-identified COVID patient in a less-protective surgical mask are typically sent home for two weeks, he said.

Outside of academic medicine, though, front-line staff have turned to union leaders to push for such protections.

In Southern California, leaders of the National Union of Healthcare Workers filed an official complaint with state hospital inspectors about the risks posed by intermingled COVID patients at Fountain Valley Regional Hospital in Orange County, part of for-profit Tenet Health. There, the complaint said, patients were not routinely tested for COVID-19 upon admission.

One nursing assistant spent two successive 12-hour shifts caring for a patient on a general medical floor who required monitoring. At the conclusion of the second shift, she was told the patient had just been found to be COVID-positive.

The worker had worn only a surgical mask — not an N95 respirator or any form of eye protection, according to the complaint to the California Department of Public Health. The nursing assistant was not offered a COVID test or quarantined before her next two shifts, the complaint said.

The public health department said it could not comment on a pending inspection.

Barbara Lewis, Southern California hospital division director with the union, said COVID patients were on the same floor as cancer patients and post-surgical patients who were walking the halls to speed their recovery.

She said managers took steps to separate the patients only after the union held a protest, spoke to local media and complained to state health officials.

Hospital spokesperson Jessica Chen said the hospital “quickly implemented” changes directed by state health authorities and does place some COVID patients on the same nursing unit as non-COVID patients during surges. She said they are placed in single rooms with closed doors. COVID tests are given by physician order, she added, and employees can access them at other places in the community.

It’s in contrast, Lewis said, to high-profile examples of the precautions that might be taken.

“Now we’re seeing what’s happening with baseball and basketball — they’re tested every day and treated with a high level of caution,” Lewis said. “Yet we have thousands and thousands of health care workers going to work in a very scary environment.”

Nursing Homes Face Penalties

More than 40% of the people who’ve died of COVID-19 lived in nursing homes or assisted living facilities, researchers have found.

Patient mixing has been a scattered concern at nursing homes, which Medicare officials discovered when they reviewed infection control practices at more than 15,000 facilities.

News reports have highlighted the problem at an Ohio nursing home and at a Maryland home where the state levied a $70,000 fine for failing to keep infected patients away from those who weren’t sick — yet.

Another facing penalties was Fair Havens Center, a Miami Springs, Florida, nursing home where inspectors discovered that 11 roommates of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 were put in rooms with other residents — putting them at heightened risk.

Florida regulators cut off admissions to the home and Medicare authorities levied a $235,000 civil monetary penalty, records show.

The vice president of operations at the facility told inspectors that isolating exposed patients would mean isolating the entire facility: Everyone had been exposed to the 32 staff members who tested positive for the virus, the report says.

Fair Havens Center did not respond to a request for comment.

In Iowa, Medicare officials declared a state of “immediate jeopardy” at Pearl Valley Rehabilitation and Care Center in Muscatine. There, they discovered that staffers were in denial over an outbreak in their midst, with a nursing director overriding a community doctor’s orders to isolate or send residents to the emergency room. Instead, officials found, in late April, the assistant nursing director kept COVID patients in the facility, citing a general order by their medical director to avoid sending patients to the ER “if you can help it.”

Meanwhile, several patients were documented by facility staff to have fevers and falling oxygen levels, the Medicare inspection report shows. Within two weeks, the facility discovered it had an outbreak, with 61 residents infected and nine dead, according to the report.

Medicare officials are investigating Menlo Park Veterans Memorial Home in New Jersey, state Sen. Joseph Vitale said during a recent legislative hearing. Resident council president Glenn Osborne testified during the hearing that the home’s residents were returned to the same shared rooms after hospitalizations.

Osborne, an honorably discharged Marine, said he saw more residents of the home die than fellow service members during his military service. The Menlo Park and Paramus veterans homes — where inspectors saw dementia patients with and without the virus commingling in a day room — both reported more than 180 COVID cases among residents, 90 among staff and at least 60 deaths.

A spokesperson for the homes said he could not comment due to pending litigation.

“These deaths should not have happened,” Osborne said. “Many of these deaths were absolutely avoidable, in my humble opinion.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

What Is the Risk of Catching the Coronavirus on a Plane?

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis tried to alleviate fears of flying during the pandemic at an event with airline and rental car executives. “The airplanes have just not been vectors when you see spread of the coronavirus,” DeSantis said during a discussion at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport on Aug. 28. “The evidence is the evidence. And I think it’s something that is safe for people to do.”

Is the evidence really so clear?

DeSantis’ claim that airplanes have not been “vectors” for the spread of the coronavirus is untrue, according to experts. A “vector” spreads the virus from location to location, and airplanes have ferried infected passengers across geographies, making COVID-19 outbreaks more difficult to contain. Joseph Allen, an associate professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard University called airplanes “excellent vectors for viral spread” in a press call.

In context, DeSantis seemed to be making a point about the safety of flying on a plane rather than the role airplanes played in spreading the virus from place to place.

When we contacted the governor’s office for evidence to back up DeSantis’ comments, press secretary Cody McCloud didn’t produce any studies or statistics. Instead, he cited the Florida Department of Health’s contact tracing program, writing that it “has not yielded any information that would suggest any patients have been infected while travelling on a commercial aircraft.”

[khn_slabs slabs=”241887″ view=”inline” /]

Florida’s contact tracing program has been mired in controversy over reports that it is understaffed and ineffective. For instance, CNN called 27 Floridians who tested positive for COVID-19 and found that only five had been contacted by health authorities. (The Florida Department of Health did not respond to requests for an interview.)

In the absence of reliable data, we decided to ask the experts about the possibility of contracting the virus while on a flight. On the whole, airplanes on their own provide generally safe environments when it comes to air quality, but experts said the risk for infection depends largely on policies airlines may have in place regarding passenger seating, masking and boarding time.

So How Safe Is Air Travel?

According to experts, the risk of catching the coronavirus on a plane is relatively low if the airline is following the procedures laid out by public health experts: enforcing mask compliance, spacing out available seats and screening for sick passengers.

“If you look at the science across all diseases, you see few outbreaks” on planes, Allen said. “It’s not the hotbed of infectivity that people think it is.”

Airlines frequently note that commercial planes are equipped with HEPA filters, the Centers for Disease Control-recommended air filters used in hospital isolation rooms. HEPA filters capture 99.97% of airborne particles and substantially reduce the risk of viral spread. In addition, the air in plane cabins is completely changed over 10 to 12 times per hour, raising the air quality above that of a normal building.

Because of the high air exchange rate, it’s unlikely you’ll catch the coronavirus from someone several rows away. However, you could still catch the virus from someone close by.

“The greatest risk in flight would be if you happen to draw the short straw and sit next to or in front, behind or across the aisle from an infector,” said Richard Corsi, who studies indoor air pollution and is the dean of engineering at Portland State University.

It’s also important to note that airplanes’ high-powered filtration systems aren’t sufficient on their own to prevent outbreaks. If an airline isn’t keeping middle seats open or vigilantly enforcing mask use, flying can actually be rather dangerous. Currently, the domestic airlines keeping middle seats open include Delta, Hawaiian, Southwest and JetBlue.

The reason for this is that infected people send viral particles into the air at a faster rate than the airplanes flush them out of the cabin. “Whenever you cough, talk or breathe, you’re sending out droplets,” said Qingyan Chen, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University. “These droplets are in the cabin all the time.”

This makes additional protective measures such as mask-wearing all the more necessary.

Chen cited two international flights from earlier stages of the pandemic where infection rates varied depending on mask use. On the first flight, no passengers were wearing masks, and a single passenger infected 14 people as the plane traveled from London to Hanoi, Vietnam. On the second flight, from Singapore to Hangzhou in China, all passengers were wearing face masks. Although 15 passengers were Wuhan residents with either suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19, the only man infected en route had loosened his mask mid-flight and had been sitting close to four Wuhan residents who later tested positive for the virus.

Traveling Is Still a Danger

Even though flying is a relatively low-risk activity, traveling should still be avoided unless absolutely necessary.

“Anything that puts you in contact with more people is going to increase your risk,” said Cindy Prins, a clinical associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Florida College of Public Health and Health Professions. “If you compare it to just staying at home and quick trips to the grocery store, you’d have to put it above” that level of risk.