This post was originally published on this site

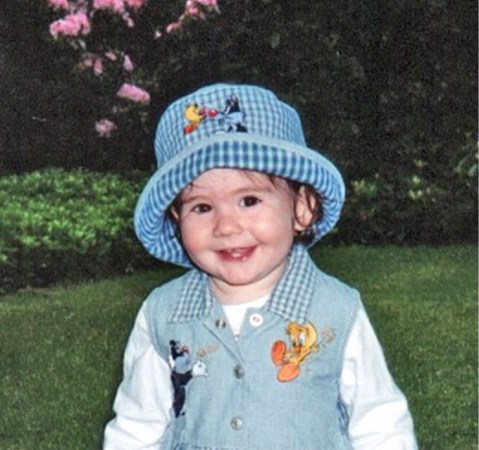

In 1997, at 15 and a half months old, Maria Crandall was developing well and the “happiest little kid,” says her mom Laura Gould, a research scientist at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “There was no concern.”

One night, Maria developed a fever. By the next morning, she “seemed to be back to her happy self.” Yet after Maria’s nap later that day, Gould couldn’t wake her. Gould started CPR. Emergency medical technicians quickly arrived and took Maria to the emergency room. But Gould’s daughter had died in her sleep.

“You think it’s going to be like TV and, you know, all of the sudden they’re going to wake up,” Gould says. “And it was just too late.”

Gould thought she must have missed something. But the medical examiner couldn’t find anything wrong from the autopsy. The mystery of Maria’s death led Gould to help bring into existence a whole field of research on unexpected deaths in children.

Sudden unexplained death in childhood, or SUDC, is a category of death for children age 1 and older. It means that after an autopsy and review of the child’s medical history and circumstances of the death, there remains no explanation for why the child died. These deaths most often occur when a child is sleeping.

In the United States, around 400 children age 1 and older die without an explanation each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The majority of these deaths affect younger children, those who are 1 to 4 years old. SUDC is much rarer than sudden unexpected infant death, or SUID; around 3,400 babies die unexpectedly each year in the United States. SUID includes sudden infant death syndrome along with other unexpected deaths in children younger than 1 year old.

After her daughter died in 1997, Gould, then a neurological physical therapist, searched for answers. The only information she could find was about infants who unexpectedly died. She attended a conference on sudden infant deaths in 1999 and met pathologist Henry Krous of Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. Gould and Krous cofounded the San Diego SUDC Research Project, the first big effort to study sudden unexplained deaths in children. The project collected available information on SUDC cases, including autopsy reports and medical records, and developed a questionnaire for parents. Researchers reviewed the material to look for commonalities among these deaths.

Looking for clues to help unravel SUDC

One clue that emerged from the project was an association between SUDC and seizures that are due to fevers. These febrile seizures occur in about 2 to 4 percent of kids younger than 5 years old and are generally considered harmless by the medical community. But the seizures turned out to be a prevalent feature in the medical histories of children affected by SUDC. A study that included 49 toddlers with SUDC found that 24 percent had a history of febrile seizures, Krous, Gould and colleagues reported in 2009. Subsequent research has found that close to 30 percent of children with unexplained death have a history of febrile seizures.

The San Diego SUDC Research Project continued until 2012, when Krous retired. Gould went on to work with neurologist Orrin Devinsky of New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. Devinsky is an expert in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, a brain disorder marked by recurring seizures. In 2014, Gould, Devinsky and others set up the SUDC Foundation to provide families with information and support and to raise research funds. The same year Gould and Devinsky started the SUDC Registry and Research Collaborative at NYU Langone Health, with an eye towards expanding the types of studies they could do and the biological specimens and other information they collected.

Families learn about the NYU registry on their own or through the foundation. Medical examiners refer SUDC cases to the registry too, sometimes before the autopsy has started. This means that, with the parents’ consent, the registry can acquire the whole brain to look for differences in children with SUDC. The NYU registry includes more than 350 families, Gould says. Over 80 percent of the children died at the ages of 1 to 4 years old.

Gould works with families as they are deciding whether to enroll. At times, she is speaking with people hours to days after their lives have changed forever. Gould remembers the “absolute numbness” she felt when her daughter died. When she talks to families, she tells them about her experience and “that they can ask me anything they want whether they enroll in the research or not — that I’m there to support them.”

Video evidence of seizures before SUDC

Over time, some enrolled families have been able to provide videos from crib cameras or home security systems. These images of their sleeping children had unexpectedly captured their final moments.

A team of forensic pathologists and neurologists who specialize in epilepsy reviewed seven videos the registry received, of children who were 13 to 27 months old. Six of the children appeared to have a seizure shortly before they died, Gould, Devinsky and the team reported online in Neurology in January. After the seizure, some of the children appeared to have irregular or labored breathing before they became still.

The videos add evidence that seizures probably play a prominent role in SUDC, Gould says. Yet why these brief seizures are followed by the death of these children still isn’t known. The team didn’t have heart rate or brain activity information for the kids in the video study. But a study of people who experienced sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, which often occurs during or after a seizure, may offer some clues, Gould says. These people were being evaluated in epilepsy monitoring units, from which heart rate, brain activity and other information was available. Those who died unexpectedly exhibited heart rate and breathing disturbances beforehand.

“The vast, vast majority of children with febrile seizures will do just fine,” Gould says. “We don’t want to scare everyone.” A big part of the research is figuring out how to identify the children at risk, she says. That would also inform recommendations for families — perhaps including some type of monitoring during sleep for vulnerable children — and guidelines that pediatricians can offer.

This 25-years-and-counting research endeavor wouldn’t have gotten to this point without the efforts of many, Gould says, including scientists from many disciplines, medical examiners and the families — “The families, who say, this is the worst thing that’s ever happened to me, learn as much as you can from it to help someone else.”

When Maria died, many medical professionals told Gould her daughter was the only such case they’d ever encountered. Having no one who could relate to her experience was incredibly isolating, she says. Now, when talking to grieving parents, “one of the things I always want every family to know is that you’re not alone.”