This post was originally published on this site

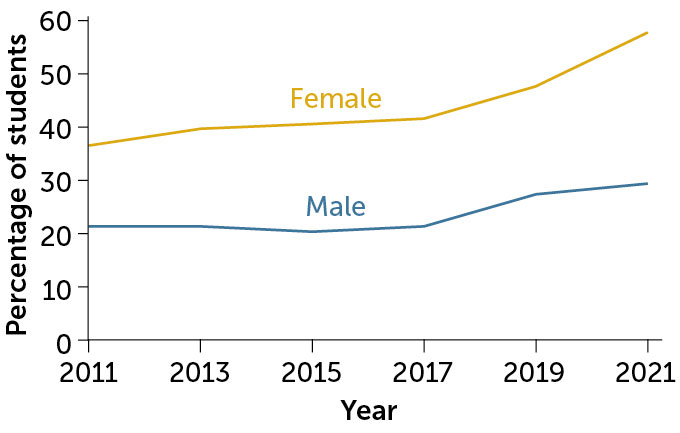

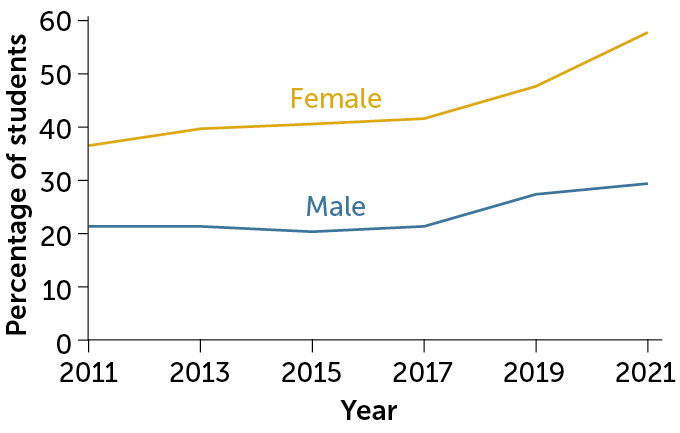

Teenagers in the United States are in crisis. That news got hammered home earlier this year following the release of a nationally representative survey showing that over half of high school girls reported persistent feelings of “sadness or hopelessness” — common words used to screen for depression. Almost a third of teenage boys reported those same feelings.

“No one is doing well,” says psychologist Kathleen Ethier. She heads the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Adolescent and School Health, which has overseen this biennial Youth Risk Behavior Survey since 1991.

During the latest round of data collection, in fall 2021, over 17,000 students from 31 states responded to roughly 100 questions related to mental health, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, sexual behavior, substance use and experiences of violence.

One chart in particular garnered considerable media attention. From 2011 to 2021, persistent sadness or hopelessness in boys went up 8 percentage points, from 21 to 29 percent. In girls, it rose a whopping 21 percentage points, from 36 to 57 percent.

Some of that disparity may arise from the fact that girls in the United States face unique stressors, researchers say. Compared with boys, girls seem more prone to experiencing mental distress from social media use, are more likely to experience sexual violence and are dealing with a political climate that is often hostile to women’s rights (SN: 7/16/22 & 7/30/22, p. 6).

But the gap between boys and girls might not be as wide as the numbers indicate. Depression manifests differently in boys and men than in girls and women, mounting evidence suggests. Girls are more likely to internalize feelings, while boys are more likely to externalize them. Rather than crying when feeling down, for instance, boys may act irritated or lash out. Or they may engage in risky, impulsive or even violent acts. Inward-directed terms like “sadness” and “hopelessness” miss those more typically male tendencies. And masculine norms that equate sadness with weakness may make males who are experiencing those emotions less willing to admit it, even on an anonymous survey.

Consequently, screening tools, such as the one used by the CDC’s survey, may miss depression in about 1 in 10 males, research suggests.

“We need to have more of a recognition that boys and men, some of them, not all of them, are suffering,” says clinical psychologist Ryon McDermott of the University of South Alabama in Mobile. “And we miss them. We miss them in our assessments, and we miss them in our discussions.”

Diagnosing depression in boys and men

The idea of overlooked depression in men is not new. Take what happened on the Swedish island of Gotland. In the 1960s and ’70s, suicide rates were high. So in 1983, health officials launched an education program for Gotland doctors on depression treatment and suicide prevention.

At first, the program looked like a resounding success. The island’s overall suicide rate dropped from roughly 20 out of every 100,000 people in 1982 to roughly 7 out of every 100,000 people by 1985, researchers reported in the 1992 Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

But a subsequent, deeper analysis showed that the decline was almost entirely among women. In the 2½ years before and after the program, the number of women dying by suicide decreased from 11 to two, while the number of men dying by suicide mostly stayed steady, seeing a marginal decline from 16 to 15.

Men struggling with suicidal thoughts appear less likely to seek help and more likely to have doctors ignore their depressive symptoms when they do seek help, Wolfgang Rutz, then a psychiatrist at a Gotland hospital, theorized in 1996 in the Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. Doctors observed, for instance, that men who were depressed often didn’t present with classic symptoms, such as sadness, but instead presented as hostile, impulsive and aggressive.

Rutz suspected that this gender disparity in diagnosis and treatment might underpin why, at the time, men in Sweden were being diagnosed with depression half as often as women but dying by suicide five times as often. Without obvious signs of depression, Rutz noted, to the outside observer, many male suicides occurred seemingly without warning.

“The criteria of depression that are taught in psychiatric textbooks and diagnostic manuals today and which also have been used in the Gotland project seem insufficient in detecting the typical masculine way of being depressive,” Rutz wrote.

Rutz went on to develop a screening tool for male depression, which paved the way for more recent male-specific tools. They include the Male Depression Risk Scale, developed by Simon Rice, a clinical psychologist at Orygen, an Australian nonprofit research, clinical and advocacy institute focused on youth mental health.

The scale focuses on emotion suppression, anger and aggression; drug and alcohol use; somatic symptoms, such as concerns about sleep and sex; and risk-taking. Participants rate various statements, such as how often they bottle up negative feelings, have difficulty managing anger or use drugs for temporary relief. None of the questions ask about sadness or hopelessness.

Research shows that some men meet the criteria for depression on the Male Depression Risk Scale but not on more traditional scales. In a recent study of 1,000 Canadian men, Rice and his team found that 80 respondents, or 8 percent, met the criteria for depression only on a traditional scale that includes a question about how often the respondent has felt “down, depressed or hopeless.” In addition, 120 respondents, or 12 percent, met the criteria on both scales. But 110 respondents, or 11 percent, met the criteria for depression only on the men’s scale, the team reported in 2020 in the Journal of Mental Health.

The results suggest that had the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey included a male-specific question about depression, there might still have been a gender gap but perhaps a smaller one.

Too many boys and men are suffering in silence, says Rice, who is also a principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne. Ten or 11 percent of missed cases “might sound like a small percentage,” he says, “but at the population level, that is huge.”

Is it depression or something else?

The idea that acting out and aggression could, on occasion, constitute symptoms of depression remains controversial.

The CDC, Ethier says, has relied on extensive research in formulating its survey’s depression-related question, which reads: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?”

“That item is actually quite good at predicting who has depressive symptoms,” Ethier says, adding that such accuracy holds true for both girls and boys.

That’s not to say that boys aren’t struggling, Ethier says. Anecdotally, for instance, teachers are reporting a spike in behavioral problems in their classrooms, particularly among boys. But rather than indicating depression, Ethier says, such behavior is emblematic of the broader mental health crisis among teens.

That might sound like splitting hairs. If boys are distressed, why not label them as depressed? Providing the proper diagnosis matters for appropriate treatment and future health outcomes, Ethier says. “We know that depressive symptoms in adolescence have long-term implications for health and mental health. I don’t know that the research is as conclusive about that for behavioral issues in the classroom.”

For McDermott, who studies the difficulties of measuring depression, such behavioral problems could indicate other disorders, chiefly attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. But he has no doubt that some of those boys are depressed. “It is hard to say with 100 percent certainty that all boys who are acting out are experiencing depression, but it is a good bet that many of them are,” he says.

The core symptoms of depression, whether internal or external in nature, are the same in men and women, McDermott says. But on a depression scale focusing on internalizing symptoms such as sadness or hopelessness, a depressed man would, on average, score lower than an equally depressed woman.

Why those baselines vary by gender isn’t entirely clear, McDermott says. But when it comes to hopelessness, evidence suggests that boys might sometimes suppress those feelings in adherence to male norms that discourage vulnerability. Consider the results of a review of 74 studies with a total sample size of more than 19,000 mostly U.S. participants published in 2017 in the Journal of Counseling Psychology. High scores on a scale measuring conformity to Western masculine norms, such as emotional control, self-reliance and power over women, were linked with poorer mental health, including depression, and a reduced likelihood of seeking help.

Gender norms become entrenched during the teen years, says Leslie Adams, a behavioral researcher at Johns Hopkins University. That’s when boys are really absorbing messages around masculinity from friends, family and social media. “Endorsing feelings of sadness and hopelessness kind of goes against these learned, general scripts,” Adams says.

Those male scripts are poorly understood, say Adams and others studying male mental health, because most gender research focuses on girls and women.

For instance, take research into social media use. Ethier points to the popularity of male social media personalities espousing harmful attitudes toward women, such as TikToker Andrew Tate, who was recently arrested in Romania on suspicion of human trafficking. Anecdotally, Tate and influencers like him are one way boys come to understand the world, but data on the influence of social media on boys are sparse, Ethier says.

“We focus a lot on the ways that social media might be impacting girls in terms of body image,” she says. “I don’t think we focus enough of the conversation on what is being portrayed to boys.”

The resulting knowledge gap about boys’ lives affects all of society. “It is difficult to see that we can effectively address the health of boys and young men, achieve gender equity for girls and young women, or achieve rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth, without tackling the masculine identities adopted by boys in adolescence,” a group of pediatric health experts wrote in a commentary in 2018 in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Depression’s link to suicide

Just as Rutz observed on the island of Gotland, missing depression in boys and men can come with high stakes.

“Depression can manifest in many ways … beyond sadness and hopelessness,” Adams says. “When we don’t assess the other ways that depression can manifest, there are implications. One is suicide.”

Adams suspects that the same tendency to frame depression as an internal emotion also influences how researchers ask about suicide. For instance, asking about who has considered suicide or made a plan, as the CDC does in its youth survey, reflects the belief that the respondent is both ruminating and thinking ahead. “For boys, [suicide] may not have that linear path,” Adams says. “We’re missing … impulsivity.”

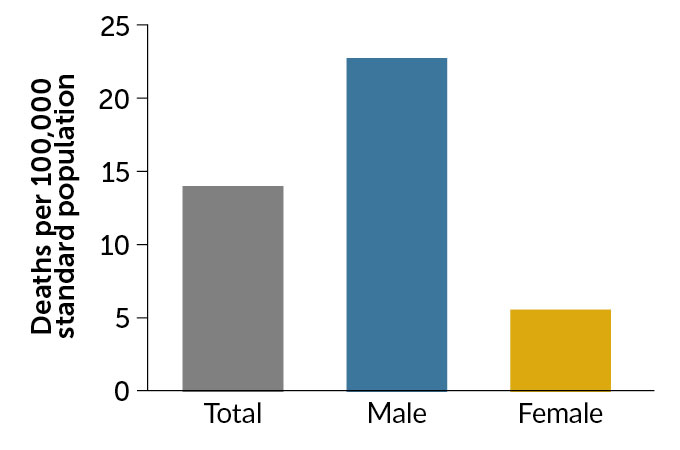

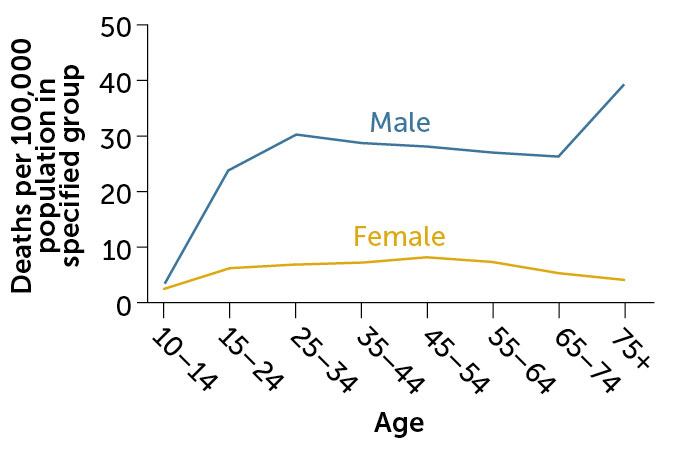

That could help explain why, in the CDC survey, teen girls reported higher levels of suicidal thinking, planning and attempts than boys, despite the fact that boys die by suicide at higher rates. Provisional federal data show that, in 2021, roughly 6 of every 100,000 girls ages 15 to 24 died by suicide. That’s compared with roughly 24 of every 100,000 boys of the same age. From 2020 to 2021, the rate of suicide in that age group increased 5 percent in girls compared with 8 percent in boys.

Access to guns might factor in here. For every 10 percent increase in household gun ownership in a state, the youth suicide rate increases by about 27 percent, researchers reported in 2019 in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. And boys are seven times as likely to kill themselves with a gun than girls are, according to a 2022 report by Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun violence prevention organization.

Missed depression in boys could help explain a long-standing research question, Adams and others say: Why do more women get diagnosed with depression, the most common precursor to suicide, when more men die by suicide?

One path forward is to look beyond sadness and hopelessness as proxies for depression, Adams says. What about impulsivity, conflict with others or social withdrawal? Perhaps those symptoms serve as better proxies for depression — and suicidal thinking — in men, she says.

Understanding other proxies could protect not just depressed individuals from harm but also broader society, another line of research suggests. Seena Fazel, a forensic psychiatrist at the University of Oxford, and colleagues began examining data from Swedish patient registries to investigate if depression links to violent behavior. Their participant pool included about 47,000 adults diagnosed with depression from 2001 to 2009 and nearly 900,000 people without such a diagnosis.

People with depression were three times as likely to commit a violent crime, such as assault, arson or a sexual offense, as individuals without depression, the team reported in 2015 in Lancet Psychiatry.

To attempt to rule out genetic or environmental differences, the team looked at siblings. A person with depression was twice as likely to commit a violent crime as their sibling without depression. Fazel and another team reported a similar link between depression and violence among teens and young adults in 2017 in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

The link between violence and depression has been found for both men and women. But since men commit most violent crimes, missing depression in men is a concern, Fazel says.

But he stresses the importance of keeping such findings in perspective. His earlier work, for instance, found that over a 13-year period in Sweden, there were 450 violent crimes committed per 10,000 people. Of those, 24 were committed by people with severe mental illness. “With guns and mental illness,” Fazel says, “you are much more likely to kill yourself than kill somebody else.”

Shifting views on depression

The idea that depression may look different in men and women — not to mention differences based on other demographic factors (SN: 2/11/23, p. 18) — is gaining traction.

For instance, a 2022 revision to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, the American Psychiatric Association’s reference book, acknowledges the gender differences in depression. The revision’s authors note that, compared with depressed women, depressed men tend to report “greater frequencies and intensities of maladaptive self-coping and problem-solving strategies, including alcohol or other drug misuse, risk-taking and poor impulse control.”

Even before the revision, the DSM included “irritable mood” as a feature of depression in youngsters. So teenagers’ age and gender both potentially influence how they express depression.

Even if the idea that depression looks different in boys and girls gains wider acceptance, changing the Youth Risk Behavior Survey will take time. If enough experts express concerns about how questions related to mental health are posed, then the earliest the CDC could amend the survey would be for the 2025 round of data collection, a CDC spokesperson told Science News.

But the experts I spoke with are hopeful that such changes will trickle into other mainstream research. Even adding a single word to questions, such as asking about irritability in addition to sadness and hopelessness, could identify a huge number of depressed boys who might otherwise appear fine, these researchers argue.

Tweaks of this nature, Rice says, “could be a game changer at identifying depression in boys [and] young men.”