This post was originally published on this site

Languishing. The term captured the zeitgeist in April 2021 when organizational psychologist Adam Grant penned an article in the New York Times titled, “There’s a name for the blah you’re feeling: It’s called languishing.”

“Languishing is the neglected middle child of mental health. It’s the void between depression and flourishing — the absence of well-being,” wrote Grant, of the University of Pennsylvania.

The idea struck a chord with readers, and Grant’s ode to languishing went on to become the newspaper’s most read article of the year. Even I, generally suspicious of fads, felt the idea’s lure. Yes, I thought to myself, that explains a lot.

But I began to question my gut reaction to Grant’s piece after stumbling across several articles on flourishing in the December SSM-Mental Health — all part of a series spearheaded by medical anthropologist Sarah Willen.

The study of how and why people flourish anchors a subfield of psychology known as positive psychology and includes related areas of research into happiness, well-being and resilience. In this research, flourishing refers to an optimal state of mental well-being, where one is happy, satisfied with life and has a sense of purpose.

Positive psychologists tend to believe that anyone can flourish if they just try hard enough, says Willen, of the University of Connecticut in Storrs. Consequently, she says, these researchers tend to downplay systemic barriers to flourishing, such as those related to race or class.

Positive psychologists “presume that people have a good measure of control over what they are able to do in life,” Willen says. But her own research, and that of others, shows that societal forces limit that control for many people.

In one article in the SSM-Mental Health series, Willen zooms in on Grant’s column to argue that its languishing framing speaks to the privileged few, and illustrates how the elite and powerful often capture the narrative during historic moments while eliding the lived experience of people lower on the social totem pole.

The rise of positive psychology

Positive psychology is a relatively young field. In the late 1990s, when psychologist Martin Seligman of the University of Pennsylvania took over as president of the American Psychological Association, he sought to reverse the field’s traditional focus on mental illness and focus instead on mental well-being. Since that time, positive psychology has emerged as a leading paradigm for research into mental health, writes Willen in her introduction to the mental health series.

The field has garnered enormous public and private investments: The Templeton Foundation, for example, currently funds the Global Flourishing Study, a $43.4 million initiative at Harvard University that will look at flourishing across time among 240,000 participants from 22 countries.

Meanwhile, the study of human flourishing and its effects has permeated well beyond psychology research. The concept now shows up frequently in research on preventive medicine and physical health, and in K-12 schools through what’s known as positive education, where, the idea goes, positive schools and positive teachers who “transmit optimism, trust and a hopeful sense of the future … are the fulcrum for producing more well-being in a culture.”

But some researchers remain skeptical of positive psychology. For one, the field largely emphasizes individual-level — not societal — changes to help people flourish, such as practicing gratitude and volunteering. That risks reducing the study of flourishing to simple self-help tricks, Willen says. What’s more, this individualized view of flourishing helps fuel the incredibly powerful and profitable self-help industry, say Willen and others.

“Positive psychology is a billion-dollar industry, and selling positivity as they do is incredibly lucrative and culturally seductive,” says Oksana Yakushko, a practicing psychologist in Santa Barbara, Calif.

But, she says, the field ignores many people’s realities. “I am troubled by the socio-political implications of selling this positive psychology ideology in a world where human beings are consistently abused, traumatized, and stressed because they are not white, wealthy, able-bodied, Western, heterosexual, etc.”

What does it mean to flourish?

With positive psychology capturing money and attention, Willen began thinking a few years ago about how to push back against the movement. Decades of research into public health have made clear that thriving in life depends at least as much on a person’s environment and circumstances as their individual attributes, she says. “There are times in life when you feel like you just have to say something. It feels really important [to] bring a perspective from another discipline.”

So from 2018 to 2019, Willen and her team conducted a qualitative study of flourishing in Cleveland. Their 167-person pool of participants reflected the city’s economic and racial diversity. The team sought to understand how people conceived of flourishing through a series of open-ended questions beginning with: “Would you describe yourself as someone who’s flourishing at this point in your life? Why or why not?”

Roughly half of the participants said they were flourishing, the team reported in the December SSM-Mental Health. But the researchers also identified stark racial and socioeconomic disparities in those responses.

Sixty-seven percent of white respondents felt they were flourishing compared with 48 percent of Black respondents. Similarly, 88 percent of respondents with incomes over $100,000 reported flourishing compared with 46 percent of respondents with incomes below $30,000.

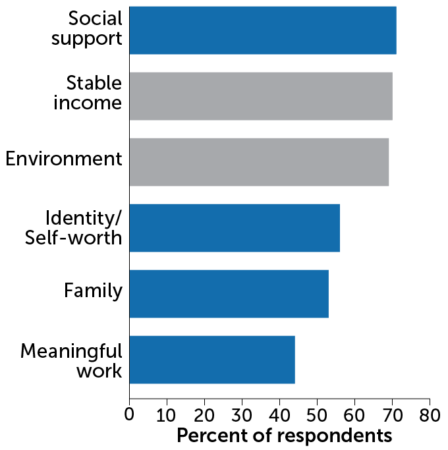

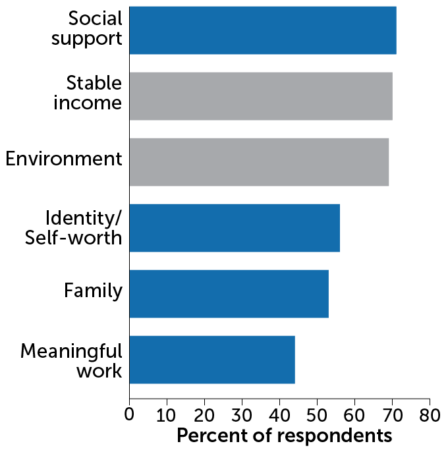

The team’s findings in response to another question — “What do people need, in general, to flourish?”— illuminated how participants’ understanding of flourishing often veered away from that of positive psychologists.

Positive psychologists tend to define someone as flourishing if they report having generally positive relationships and emotions, meaning and purpose in their life, self-acceptance or high self-esteem and deep engagement in their life’s activities. Among participants in Willen’s study, such relationships and feeling good about oneself were important to flourishing, but meaning and purpose showed up less frequently.

Most crucially, the participants in the study mentioned two aspects of flourishing that rarely figure into positive psychologists’ definitions of the term: Stable income and strong social determinants of health. The latter includes access to food, housing, education and safe neighborhoods while also experiencing low levels of discrimination.

If policy makers’ goal is to help as many people flourish as possible, then initiatives should focus on reducing inequality and mitigating those systemic barriers to well-being rather than more individualized measures, Willen says.

Is flourishing, or languishing, a privilege?

The disagreement between anthropologists and positive psychologists is largely one of world view, says Harvard University epidemiologist Tyler VanderWeele, who leads the Templeton-funded Global Flourishing Study. While Willen and her team argue that one’s environment may put happiness, or flourishing, out of reach, VanderWeele sees that world view as self-defeating.

Financial stability does comprise one of the six facets of flourishing that VanderWeele and colleagues are measuring in their global study of the concept. But for him, that facet is no more important than the other facets, which include happiness, mental and physical health, meaning and purpose, character and close social relationships.

“We do need to worry about structural conditions, financial means and trying to ensure opportunities for everyone to flourish and the means necessary for that.… [but] I don’t think those trump the other aspects of well-being,” says VanderWeele, who coauthored a rebuttal to the series in the same issue of SSM-Mental Health.

Focusing too much on factors outside any one individual’s control, such as racism or poverty, VanderWeele says, can be disempowering. Focusing on smaller factors, such as crafting one’s job to their liking or getting more involved in one’s community by joining a religious group or volunteering, meanwhile, hands that power back to the people.

This is not a debate between equals, Willen counters. With so much momentum behind their movement, positive psychologists have captured the narrative. And their self-help view of how to flourish is becoming The View, she says.

After Adam Grant’s article appeared in the Times, Willen witnessed how concepts drawn from positive psychology — in this case languishing — take on a life of their own as they enter the public domain.

That bird’s-eye view arose thanks to the Pandemic Journaling Project — an initiative Willen and other researchers launched in May 2020 to enable people from all walks of life to document how they were coping with this historic moment. Through those journal entries, the scientists observed which people glommed onto the idea that they were languishing — and who did not. Tellingly, entrants who mentioned the term skewed overwhelmingly white, wealthy and educated — a limited cohort that also reflects the readership of the Times, Willen says.

Grant uses his own arguably privileged experience of the moment to make sweeping claims about how people were experiencing the crisis, Willen says. He then uses those claims to write about how all people can overcome the blahs.

Specifically, Grant recommends people find flow. “Flow is that elusive state of absorption in a meaningful challenge or a momentary bond, where your sense of time, place and self melts away,” he writes. Such flow can arise by binge-watching shows and movies on Netflix, playing word games and, more broadly, pursuing uninterrupted time for oneself.

But just who has had the luxury to pursue such remedies for languishing, Willen asks. And who, struggling with precarity in work, health and other domains, has instead experienced something darker, something more akin to suffering?

Grant maintains that Willen is creating a “false dichotomy” between personal and systemic solutions to flourishing. Simpler behavioral interventions serve as crucial stopgap measures in challenging times, Grant adds. “It would be awfully cruel to tell readers suffering through a pandemic that they should just wait for social policies to change.”

But most people aren’t even aware of how individualized solutions to flourishing are overshadowing more systemic solutions, Willen says. Bringing that oversight to public attention is vital. “Unless we step back and ask ourselves whose voice is missing,” Willen says, “we risk internalizing a distorted account of history.”

Her words remind me of the adage: History is written by the victors. It’s a thought echoed on the Pandemic Journaling Project’s website. “Usually, history is written only by the powerful,” read the introductory words. “When the history of COVID-19 is written, let’s make sure that doesn’t happen.” That’s certainly an admonition I’ll be keeping in mind this year as I strive for balance in my reporting on positive psychology, the pandemic and other societal issues.