This post was originally published on this site

Some 230 million years ago, massive dolphinlike reptiles called ichthyosaurs gathered to breed in safe waters — just like many modern whales do.

That’s the conclusion that researchers arrived at after studying a mysterious ichthyosaur graveyard in Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in Nevada. The park is home to the world’s richest assemblage of fossils of Shonisaurus popularis, one of the largest ichthyosaurs ever discovered (SN: 8/19/02).

“This is something we see in modern marine vertebrates — gray whales make [the] trek to Baja California every year” to breed, says Randall Irmis, a paleontologist at the National History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City. The sheltered, warm water offers safety for the whales (SN: 1/19/80).

The new finding, described December 19 in Current Biology, shows that this behavior “goes back at least 230 million years,” Irmis says. “It really connects the past to the present in a big way.”

The idea of birthing areas for ichthyosaurs has been proposed previously, and is even well-known enough to often be incorporated into artists’ renderings of the creatures, says Erin Maxwell, a paleontologist at the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, Germany, who wasn’t involved in the new research. But, she says, this study “is the first to support these speculations with data.”

Nevada’s ichthyosaur fossil trove has been a puzzle to paleontologists for decades. One curiosity is the many ichthyosaur fossils clustered in what’s now the park, but about 230 million years ago, was part of a tropical sea. Another oddity is that the site seems as if it were almost entirely populated by giant, 14-meter-long adult S. popularis. And then there’s the tantalizing question of what caused the deaths.

Scientists have previously suggested that the reptiles, which could be roughly the length of a school bus when grown, had congregated together for some unknown reason before something caused their mortality en masse.

Several pockets, or quarries, of specimens are scattered across the park. All told, Irmis and colleagues identified at least 112 ichthyosaur individuals in these quarries, including at one site where park officials had left previously discovered bones half-encased in the rock for public viewing.

That death snapshot meant that scientists could examine how the fossils were arranged relative to one another, perhaps offering insight into the reptiles’ behavior, says Neil Kelley, a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

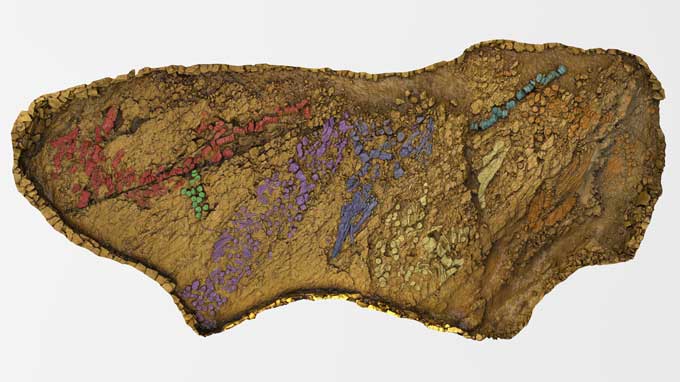

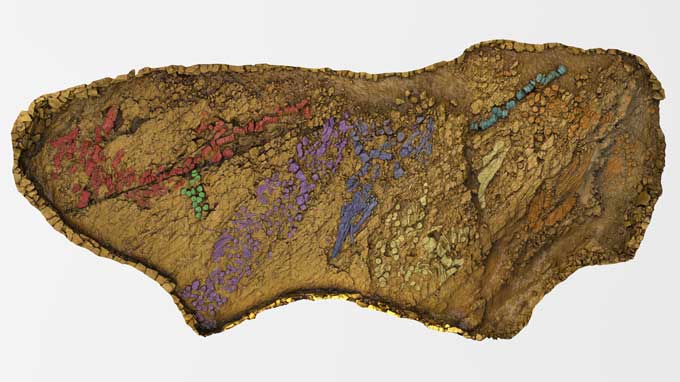

Kelley, Irmis and colleagues used digital cameras and a laser scanner to collect hundreds of measurements of the bone bed with the half-buried reptiles, combining the data into a 3-D model of the site. The team also studied the sizes and shapes of bones from across the park, including some now in museum collections. And the researchers analyzed the chemical makeup of the surrounding rocks and pored over older photographs and field notes.

These scraps of evidence helped the researchers begin to understand what they were looking at — and potentially solve at least one long-standing mystery: what brought these creatures together.

Though almost all of the park’s Shonisaurus skeletons are fully-grown adults, the site does have a few very tiny ichthyosaur remains, the scientists found. Using micro-computed tomography, a 3-D imaging technique that uses X-rays to see inside the fossils, the researchers discovered that some tiny bones were those of embryonic and newborn Shonisaurus.

The finding led the team to conclude that the site was a birthing ground. That could explain why there were so many of the same creatures in the same place alongside newborns, the researchers say.

The site also seems to have been a birthing ground for Shonisaurus for a long time. Rather than all the quarries dating to roughly the same time, different ones are separated by at least hundreds of thousands of years, the researchers found.

As for what killed the reptiles, “we don’t know,” Irmis says.

Among the hypotheses for a mass mortality event were harmful algal blooms or large-scale volcanic activity. But the new rock chemistry data eliminated those events as culprits.

Some of the animals in each quarry could have still died en masse. Having the creatures grouped in one place to breed may have left the reptiles vulnerable to a sudden catastrophic event that buried them in sediment, such as an undersea landslide.

But the fossil finds might also represent “just normal mortality over time,” Irmis says, given how the creatures seem to have come to the site again and again.