This post was originally published on this site

Across Central and South America, one group of bejeweled frogs is making a comeback.

Harlequin frogs — a genus with over 100 brightly colored species — were one of the groups of amphibians hit hardest by a skin-eating chytrid fungus that rapidly spread around the globe in the 1980s (SN: 3/28/19). The group is so susceptible to the disease that with the added pressures of climate change and habitat loss, around 70 percent of known harlequin frog species are now listed as extinct or critically engendered.

But in recent years, roughly one-third of harlequin frogs presumed to have gone extinct since the 1950s have been rediscovered, researchers report in the December Biological Conservation.

The news is a rare “glimmer of hope” in an otherwise bleak time for amphibians around the globe, says Kyle Jaynes, a conservation biologist at Michigan State University in Hickory Corners.

The comeback frog

For Jaynes, the path to uncovering how many harlequin frogs have returned from the brink of extinction started when he heard about the Jambato harlequin frog (Atelopus ignescens). This black and orange frog was once so widespread in the Ecuadorian Andes that its common name comes from the word ”jampatu,” which means “frog” in Kichwa, the Indigenous language of the area.

Then came the fungus. From 1988 to 1989, the frogs “just completely disappeared,” Jaynes says. For years, people searched for traces of the frogs. Scientists ran extensive surveys, and pastors offered rewards to their congregants for anyone that could find one.

Then in 2016, a boy discovered a small population of Jambato frogs in a mountain valley in Ecuador. For a species that had been missing for decades, “it seemed like a miracle,” says Luis Coloma, a researcher and conservationist at the Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios in Quito, Ecuador.

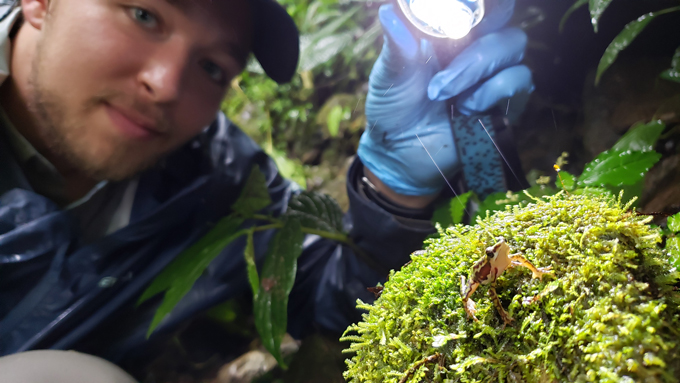

Coloma runs a breeding program for Jambato and other Ecuadorian frogs threatened with extinction. In 2019, Jaynes was part of a group of researchers visiting Coloma’s lab to see if they could work out how these frogs had cheated death. After the Jambato frogs returned to the scene, the team started hearing about other missing harlequin species being spotted for the first time in years.

Those stories led Jaynes, Coloma and their colleagues to comb through reports to see just how many harlequin frogs had reappeared. Of the more than 80 species to have gone missing since 1950, as many as 32 species were spotted in the last two decades — a much higher number than the team had expected.

“I think we were all shocked,” Jaynes says.

Ensuring conservation

The news comes with caveats. For one thing, it seems like most species avoided disappearing by a hair, and their numbers are still dangerously low. So extinction is still very much on the table. “We’ve got a second chance here,” Jaynes says. “But there is still a lot we have to do to conserve these species.”

Ensuring the continuation of the rediscovered species will depend in part on understanding how they’ve managed to survive so far. Some scientists have speculated that amphibians at higher elevations might be more susceptible to the fungus since it prefers lower temperatures.

But a cursory analysis by Jaynes and colleagues revealed that harlequin frogs are being rediscovered at all elevations across their range, indicating that something else may be at play. Jaynes suspects that there is a biological basis for which harlequin frogs live, such as having developed resistance to the fungus (SN: 3/29/18).

Studies like this one can serve as a “launching pad” for understanding how amphibians might survive the dual threats of disease and climate change, says Valerie McKenzie, a disease ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved with the study.

In the meantime, the fact that people are starting to notice the reemergence of species that were once thought to be gone forever “gives me a lot of hope that other species that are harder to observe — because they’re nocturnal or live high in the canopy — are also recovering,” she says. “It motivates me to think we should go look for them.”