This post was originally published on this site

It was the juice that tipped him off. At lunch, Ícaro de A.T. Pires found the flavor of his grape juice muted, flattened into just water with sugar. There was no grape goodness. “I stopped eating lunch and went to the bathroom to try to smell the toothpaste and shampoo,” says Pires, an ear, nose and throat specialist at Hospital IPO in Curitiba, Brazil. “I realized then that I couldn’t smell anything.”

Pires was about three days into COVID-19 symptoms when his sense of smell vanished, an absence that left a mark on his days. On a trip to the beach two months later, he couldn’t smell the sea. “This was always a smell that brought me good memories and sensations,” Pires says. “The fact that I didn’t feel it made me realize how many things in my day weren’t as fun as before. Smell can connect to our emotions like no other sense can.”

As SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, ripped across the globe, it stole the sense of smell away from millions of people, leaving them with a condition called anosmia. Early in the pandemic, when Pires’ juice turned to water, that olfactory theft became one of the quickest ways to signal a COVID-19 infection. With time, most people who lost smell recover the sense. Pires, for one, has slowly regained a large part of his sense of smell. But that’s not the case for everyone.

About 5.6 percent of people with post–COVID-19 smell loss (or the closely related taste loss) are still not able to smell or taste normally six months later, a recent analysis of 18 studies suggests. The number, reported in the July 30 British Medical Journal, seems small. But when considering the estimated 550 million cases and counting of COVID-19 around the world, it adds up.

Scientists are searching for ways to hasten olfactory healing. Three years into the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have a better idea of how many people are affected and how long it seems to last. Yet when it comes to ways to rewire the sense of smell, the state of the science isn’t coming up roses.

A method called olfactory training, or smell training, has shown promise, but big questions remain about how it works and for whom. The technique has been around for a while; the coronavirus isn’t the first ailment to snatch away smell. But with newfound pressure from people affected by COVID-19, olfactory training and a host of other newer treatments are now getting a lot more attention.

The pandemic has brought increased attention to smell loss. “If we have to provide a silver lining, COVID is pushing the science at a speed that’s never happened before,” says Valentina Parma, an olfactory researcher and assistant director of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia. “But,” she cautions, “we are really far from a solution.”

Nasal attack

Compared with sight or hearing, the sense of smell can seem like an afterthought. But losing it can affect people deeply. “Your world really changes if you lose the sense of smell, in ways that are usually worse,” Parma says. The smell of a baby’s head, a buttery curry or the sharp salty sea can all add emotional meaning to experiences. Smells can also warn of danger, such as the rotten egg stench that signals a natural gas leak.

As an ear, nose and throat doctor, Pires recalls a deaf patient who lost her sense of smell after COVID-19 and enrolled in a clinical trial that he and colleagues conducted on smell training. She worked in a perfumery company — her sense of smell was crucial to her job and her life. “At the first appointment, she said, with tears in her eyes, that it felt like she wasn’t living,” Pires recalls.

Unlike the cells that detect color or sound, the cells that sense smell can replenish themselves. Stem cells in the nose are constantly pumping out new smell-sensing cells. Called olfactory sensory neurons, these cells are dotted with molecular nets that snag specific odor molecules that waft into the nose. Once activated, these cells send messages through the skull and into the brain.

Because of their nasal neighborhood, olfactory sensory neurons are exposed to the hazards of the environment. “They may be covered with a little layer of mucus, but they’re sitting out there being constantly bombarded with bacteria and viruses and pollutants and who knows what else,” says Steven Munger, a chemosensory neuroscientist at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Gainesville.

Exactly how SARS-CoV-2 damages the smell system isn’t clear. But recent studies suggest the virus’s assault is indirect. The virus can infect and kill nose support cells called sustentacular cells, which are thought to help keep olfactory neurons happy and fed by delivering glucose and maintaining the right salt balance. That attack can inflame the olfactory epithelium, the layers of cells that line parts of the nasal cavity.

Once this tissue is riled up, the olfactory sensory neurons get wonky, even though the cells themselves haven’t been attacked. After an infection and ensuing inflammation, these neurons slow down the production of their odor-catching nets, a decrease that could blind themselves to odor molecules, scientists reported in the March 17 Cell.

With time, the inflammation settles down, and the olfactory sensory neurons can get back to their usual jobs, researchers suspect. “We do think that for post-viral smell disorders, the most common way to recover function is going to be spontaneous recovery,” Munger says. But in some people, this process doesn’t happen quickly, if ever.

That’s where smell training comes in.

A nose workout

One of the only therapies that exists, smell training is quite simple — a good old-fashioned nose workout. It involves deeply smelling four scents (usually rose, eucalyptus, lemon and cloves) for 30 seconds apiece, twice a day for months.

In one study, 40 people who had smell disorders came away from the training with improved smelling abilities, on average, compared with 16 people who didn’t do the training, olfactory researcher Thomas Hummel and his colleagues reported in the March 2009 Laryngoscope.

Since then, the bulk of studies has shown that the method helps between 30 and 60 percent of the people who try it, says Hummel, of Technische Universität Dresden in Germany. His view is that the method can help some people, “but it does not work in everybody.”

One of the nice things is that there are no harmful side effects, Hummel says. That’s “the charming side of it.” But to do the training correctly takes discipline and stamina. “If you don’t do it regularly, and you give up after 14 days, this is futile,” he says.

Pires in his recent trial had hoped to speed up the process, which usually takes three months, by adding four more odors to the regimen. For four weeks, 80 participants received either four or eight smells. Both groups improved, but there was no difference between the two groups, the researchers reported July 21 in the American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy.

It’s not known how the technique works in the people it seems to help. It could be that it focuses people’s attention on faint smells; it could be stimulating the growth of replacement cells; it could be strengthening some pathways in the brain. Data from other animals suggest that such training can increase the number of olfactory sensory neurons, Hummel says.

Overall, this nose boot camp may be a possible approach for people to try, but big questions remain about how it works and for whom, Munger says. “In my view, it’s very important to be up front with patients about the very real possibility this therapy may not lead to a restoration of smell, even if they and their doctor feel it is worth trying,” he says. “I am not trying to discourage people here, but I also think we need to be very careful not to give unwarranted promises.”

Smell training doesn’t come with harmful biological side effects, but it can induce frustration if it doesn’t work, Parma says. In her practice, “I have been talking to a lot of people who say, ‘I did it every day for six months, twice a day for 10 minutes. I met in groups with other people, so we kept each other accountable, and I did that for six months. And it didn’t work for me.’” She adds, “I would want to address the frustration that this induces in patients.”

Beyond training

Other potential treatments are coming under scrutiny, such as steroids, omega-3 supplements, growth factors and vitamins A and E, all of which might encourage the recovery of the nasal epithelium.

More futuristic remedies are also in early stages of research. These include epithelial transplants designed to boost olfactory stem cells, treatments with platelet-rich plasma to curb inflammation and promote healing, and even an “electronic nose” that would detect odor molecules and stimulate the brain directly. This cyborg-smelling system takes inspiration from cochlear implants for hearing and retinal implants for vision.

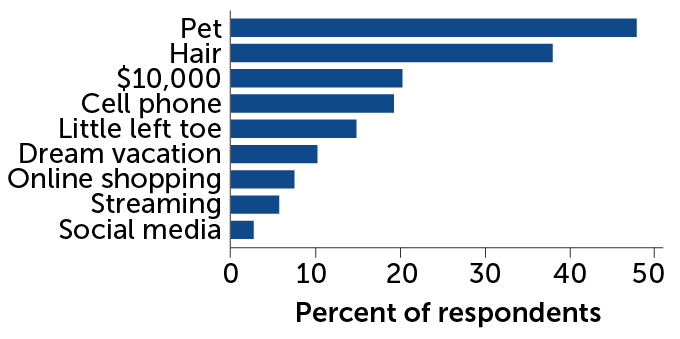

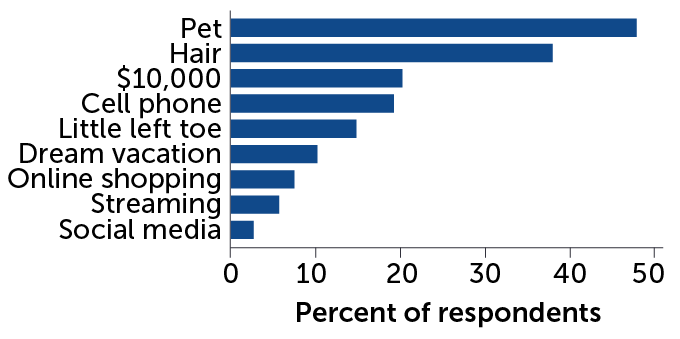

For many people, the sense of smell is appreciated only after it’s gone, Parma says, an apathy that’s illustrated in stark terms by a recent study of about 400 people. The vast majority of respondents — nearly 85 percent — would rather give up their sense of smell than sight or hearing. About 19 percent of respondents said they would prefer to give up their sense of smell than their cell phone. The survey results “dramatically illustrate the negligible value people place on their sense of smell,” researchers wrote in the March Brain Sciences.

Even as a doctor who treats people with smell loss, Pires has a newfound fondness for a good whiff. “Having lost it for a while made me appreciate it even more.”