This post was originally published on this site

Kanu Caplash was lying on a futon in a medical center in Connecticut, wearing an eye mask and listening to music. But his mind was far away, tunneling down through layer upon layer of his experiences. As part of a study of MDMA, a psychedelic drug also known as molly or ecstasy, Caplash was on an inner journey to try to ease his symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

On this particular trip, Caplash, now 22, returned to the locked bathroom door of his childhood home. As a kid, he used to lock himself in to escape the yelling adults outside. But now, he was both outside the locked door, knocking, and inside, as his younger, frightened self.

He started talking to his younger self. “I open the door, and my big version picks up my younger version of myself, and literally carries me out,” he says. “I carried myself out of there and drove away.”

That self-rescue brought Caplash peace. “I got out of there. I’m alive. It’s all right. I’m OK.” For years, Caplash had experienced flashbacks, nightmares and insomnia from childhood trauma. He thought constantly about killing himself, he says. His experiences while on MDMA changed his perspective. “I still have the memory, but that anger and pain is not there anymore.”

Caplash’s transcendent experiences, spurred by three therapy sessions on MDMA, happened in 2018 as part of a research project on PTSD. Along with a handful of other studies, that research suggests that when coupled with psychotherapy, mind-altering drugs bring some people immediate, powerful and durable relief.

Those studies, and the intense media coverage they received, have helped launch psychedelic medicine into the public conversation in the United States, England and elsewhere. Academic groups devoted to studying psychedelics have sprung up at Johns Hopkins, Yale, New York University Langone Health, the University of California, San Francisco and other research institutions. Private investors have ponied up millions of dollars for research on psychedelic drugs. The state of Oregon has started the process of legalizing therapeutic psilocybin, the key chemical in hallucinogenic mushrooms; lawmakers in other states and cities are considering the same move.

New ways to help people with PTSD, depression, anxiety and other mental health disorders are desperately needed. An estimated 30 percent of people with depression, for instance, don’t get relief from current treatments. Psychedelics, some researchers and clinicians believe, may help.

“The promise is incredible,” says Monnica Williams, a psychologist at the University of Ottawa, who ran the clinical trial Caplash participated in at UConn Health in Farmington. “Psychedelics have the potential to really completely revolutionize mental health and change everything.”

But a cloud of questions hovers over the research. It’s not known how the therapy works or who it might work for. Even if these new treatments perform well in clinical trials, the drugs, and the mind-bending experiences they bring, won’t appeal to everyone. What’s more, the drugs may not be available, or they may cost too much.

Psychedelic drugs, including MDMA, psilocybin and the hallucinogen LSD, which is also being studied as a treatment for depression and other mental health disorders, are illegal under federal law, classified as Schedule 1 substances by the U.S. government — with high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use. Many people may be reluctant to take an illegal drug that lowers their defenses and makes them vulnerable, no matter how great the promise of healing.

Social and legal hurdles, barriers to access and scientific questions make it unlikely that psychedelics will replace current mental health treatments, many experts agree. More likely is that with enough research, psychedelic substances will become another tool for doctors and therapists.

Caplash remembers what MDMA did for him right after his sessions. “I wasn’t as angry as I was before. My muscles were a lot less tense. I could literally see clearer,” Caplash says. “As I went through the study, I was also becoming a different person.”

The benefits are still with him. Caplash no longer thinks of suicide. A biology major at the University of Connecticut, he has big dreams and advocates for more accessible mental health care for others. “I feel like I’m at peace, to an extent,” he says. “I know who I am and what I want to do.”

A winding path

Psychedelic drugs are not new. Scientists at the pharmaceutical company Merck made MDMA in 1912. Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD in 1938, and Aldous Huxley popularized the drug in his 1953 book The Doors of Perception. When people talk about the psychedelic renaissance, they often begin with Hofmann and Huxley, says Sutton King, who advocates to include Indigenous voices in discussions about psychedelics and is an Afro-Indigenous member of the Menominee and Oneida Nations of Wisconsin.

But the story of psychedelics starts long before then. Indigenous communities around the world have used psilocybin and other consciousness-changing compounds for healing for thousands of years.

“The traditional Indigenous Nations … have had these connections to these medicines,” says King, who is cofounder and president of the Urban Indigenous Collective, a nonprofit advocacy group in New York City.

Belinda Eriacho, a wisdom carrier of Dine’ (Navajo) and A:shiwi (Zuni) descent, believes that psychedelic drugs, called sacred plant medicines by some Indigenous groups, are catalysts to help align mental, physical, spiritual and emotional health. “We were the knowledge keepers,” she says. “A lot of our understanding about these medicines is through practical experiences. They are not something you can read in a book.”

But around the middle of the 20th century, medical researchers, dissatisfied with existing mental health treatments, began trying to quantify these drugs’ effects on mental states. A flurry of research yielded promising hints, but many of those early attempts didn’t yield solid data. Some experiments were poorly designed; worse, some were deeply unethical, forcing high doses of psychedelics on people who were incarcerated or experiencing psychosis. Many of those study subjects were people of color.

In the 1960s, social and political sentiments began turning against these drugs — and the counterculture they represented — in both non-Indigenous and Indigenous communities. The U.S. government criminalized the use of psychedelics to keep them out of the public’s hands. The new restrictions kept the drugs out of researchers’ hands, too.

That social shift stigmatized the drugs and whatever promise they held, says neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda, who has studied PTSD for decades at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. Current drug treatments for PTSD, such as antidepressants or sleep medications, don’t work well for some people, she says. These medicines may help with symptoms, but don’t get at the root of the problem. Psychedelics might do more, she’s come to realize.

Two years ago, when Yehuda began studying psychedelic drugs, she faced a lot of skepticism. But those dismissals have disappeared. “The general attitude in academic medicine right now is, ‘Gosh, let’s try it. Let’s see. Maybe it will be good. Wouldn’t that be nice?’ ”

In some ways, psychedelics can outperform approved psychiatric drugs such as Prozac and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. And so far, the data suggest psychedelics work quickly, appear to be safe and have lasting effects, says Atheir Abbas, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. “That is hard to come by. I think that is extremely exciting.”

In the last five years, a handful of high-quality, albeit small, studies have suggested tremendous benefits from the psychedelic psilocybin for depression, anxiety and PTSD. The studies differ in their details, but many follow a similar arc. Generally, the studies begin with talk therapy sessions, followed by several therapy sessions in which participants are under the influence of a psychedelic drug. More psychotherapy comes afterward. At certain points in the process, researchers measure the participants’ symptoms.

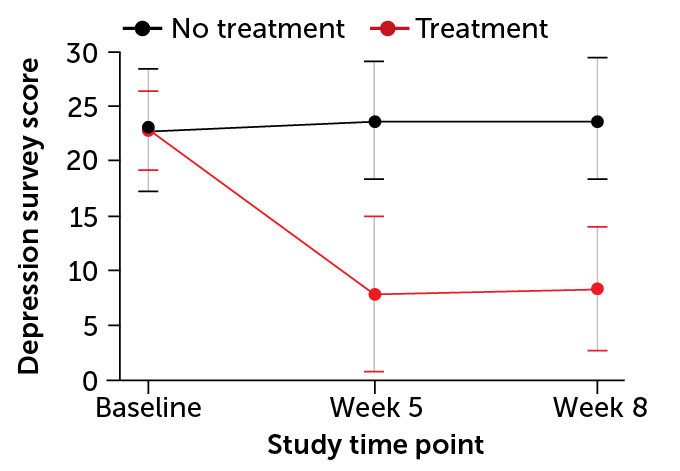

Psilocybin-assisted therapy quickly reduced signs of depression among 24 participants with moderate or severe depression, scientists reported in 2020 in JAMA Psychiatry. Four weeks after two psilocybin sessions, 71 percent of the participants had maintained a drop of at least 50 percent in their scores on a depression rating scale called the GRID-HAMD.

Earlier work showed psilocybin could help with depression and anxiety in patients facing life-threatening cancer; the benefits were still there about four years after the psilocybin treatment, researchers reported in the Journal of Psychopharmacology in 2020.

MDMA therapy seemed to have similar effects in an international study of 90 people with PTSD. Two-thirds of those who got MDMA no longer qualified for a PTSD diagnosis at the end of the trial, compared with about one-third of participants who received placebos. Those results appeared May 10 in Nature Medicine.

Collectively, the studies offer strong hints that psilocybin, MDMA and other psychedelic drugs can help in these research settings, says Scott Thompson, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. “All of them are giving the same sort of signal,” he says.

We’re in a moment when Western research is converging with the long history of Indigenous knowledge, King says. There is a place for both approaches, “two truths,” as King puts it, when it comes to helping people with psychedelic drugs.

King adds that the excitement coming from laboratories is accompanied by fear for some Indigenous people: fear of their ceremonies being appropriated, fear of worsening access to their medicines and fear of these substances being misunderstood. “It’s an exciting time, but it’s also a scary time for Indigenous peoples,” she says.

The healing components

One big question is how the various psychedelic drugs work. “If you look at all the knobs people are turning, it’s really not known what’s critical and what’s not,” Abbas says. The talk therapy that often goes with the drugs, the psychedelic trip or other drug effects could all be important.

Some people suspect that the psychotherapy is the healing component, not the drug itself. And plenty of data show that therapy works well for some people. Many of the key trials so far have been testing the drug in tandem with intense psychotherapy. Caplash, for instance, had multiple therapy sessions before, during and after his MDMA experiences. Similarly intense therapy sessions happened for people in the trial of psilocybin for depression. The drugs might make a person open to exploring some of the painful events of their past during therapy.

Others suspect that the psychedelic trip itself, the hallucinatory experience, is a crucial part of the treatment. That’s a hard question to study, but not impossible, Yehuda says. “We need the science to understand what transformation looks like, and how a drug facilitates it,” she says. “We’ve been afraid of studying the biology of altered states, or even consciousness, because it feels so wonky and so unscientific and so subjective and woo woo. But I think we should be up for this challenge.”

Other scientists are focusing on the actions of the drugs themselves, by looking inside the brain. Thompson, for instance, suspects that it’s possible to get the benefits and skip the trip by restricting cells’ responses to serotonin, a chemical messenger that’s thought to be involved in the hallucinations. His recent study in mice hints that this just might be possible.

In the mice, Thompson and colleagues blocked a sensor thought to spark psilocybin-related hallucinations. When this serotonin-detecting receptor, called 5-HT2A, was blocked, the mice appeared to stop tripping (their heads no longer twitched). Yet, psilocybin still had antidepressive effects on the mice, restoring a lost preference for sugar water. The result raises the idea that the antidepressant effects associated with psychedelics can come without the hallucinations, the researchers reported in the April 27 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

If a similar thing could happen in people, “you could retain the benefits but block the trip,” Thompson says. “The trip is the thing that makes you have to spend all day in the hospital with a facilitator there, and makes it expensive, and keeps psychedelics from being widely used,” Thompson says. “Being able to block the trip would lower the barriers in many ways.”

Eriacho, who has used psychedelics for her own healing, says the holistic experience is what matters. Psychedelic medicines allow a person to go within, to the pockets of the mind where traumas lurk, and begin to heal. “That is what it’s done for me,” she says. But the ceremony, the ritual and the wider context were all keys to her healing.

Who will benefit?

The trials completed so far have been small and included mostly white volunteers. Williams and colleagues tallied participants in psychedelic studies from 2008 to 2017. Of the 282 people who took part (and for whom race or ethnicity data were available), just 50 were not white, the researchers wrote in 2018 in BMC Psychiatry.

People of color have been underrepresented in these studies for many reasons, says Williams, who designed her study at UConn Health to specifically look at the effects of MDMA-assisted therapy in people of color. Caplash, who is Indian-American, was the first and only person to go through the process at UConn. Soon after his participation, the trial was stopped at that site. Other enrolled volunteers there were unenrolled, says Williams, now at the University of Ottawa.

“This is a very marginalized and vulnerable group,” she says. “There were fears that if anything really bad happened [during the trial], it would reflect very badly on the university.” UConn Health spokesperson Lauren Woods says that is false. The clinical trial was stopped for a “variety of reasons,” she wrote in an e-mail to Science News, declining to provide specifics.

Without strong efforts to create inclusive studies that actively recruit a diverse group of people into the trials, train therapists of color and consider racial trauma, psychedelic drugs will not be accessible to everyone who might benefit from them, Williams says. “This needs to be an important part of what we do,” she says. “We can’t keep doing it the same way it was done in the past.”

Yehuda aims to design treatments for “the populations who need it the most,” she says. That includes combat veterans with PTSD. She and her colleagues are beginning to enroll 60 veterans in a clinical trial at the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., where Yehuda directs the Mental Health Patient Care Center. “We are hoping to enroll a lot of ethnically diverse and racially diverse people, because we already serve them,” Yehuda says. “We’ve done a lot of the trust work already.”

As part of her studies, Yehuda plans to get at the question of who the drugs might work for, and why, in part by scrutinizing biological differences between people who get relief from the psychedelics and people who don’t. “We’re going to ask these somewhat tougher questions,” she says. “There is going to be a science about who [MDMA] is particularly good for.”

Meanwhile, the people making laws and policies are impatient for the science to yield answers. In 2020, Oregon voters approved Measure 109, which provides a sanctioned way to offer people psilocybin-assisted therapy. The state’s Psilocybin Advisory Board, which includes doctors, scientists and even a mushroom biologist, has two years to figure out how the state will regulate that effort.

Abbas is on that advisory board. Speaking personally and not on behalf of that board, he says designing a system for psilocybin-based therapy is immensely complex. “It’s not just who, but it’s how you identify those folks, it’s how you regulate the providers, how you regulate the psilocybin.”

Though studies so far have mainly focused on the performance of psychedelic drugs from a scientific perspective, other considerations are important, too. Perspectives from Indigenous peoples will be sought out, Abbas says.

“There needs to be this meeting of the minds, and the openness that the scientific and Western way of thinking is not always the right way,” Eriacho says. Clinical trials, for instance, often rely on narrowly defined clinical surveys to capture symptoms. “Those are Western concepts,” she says, and from her perspective, those metrics miss a lot. “You don’t have a very comprehensive way of looking at what an individual may be experiencing,” she says.

What Oregon’s psilocybin program will ultimately look like is still anyone’s guess. The same is true for use of other psychedelics. There is no single story to be found amid all of these diverse and intersecting perspectives — Indigenous traditions, Western medicalization, social movements, eager private investors.

In the place of one story, we have many, including that of Kanu Caplash, who feels healed by an experience enabled by a psychedelic drug. His transformation was deeply personal. Yet it gives us a glimpse of something possible and powerful.

If you or someone you care about may be at risk of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, a free, 24/7 service that offers support, information and local resources: 1-800-273-TALK (8255).