This post was originally published on this site

When nobody else wanted the job, Marguerite Vogt stepped in.

Working from early morning until late at night in a small, isolated basement laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, Vogt painstakingly handled test tubes and petri dishes under a fume hood: incubating, pipetting, centrifuging, incubating again. She was trying to grow a dangerous pathogen: poliovirus.

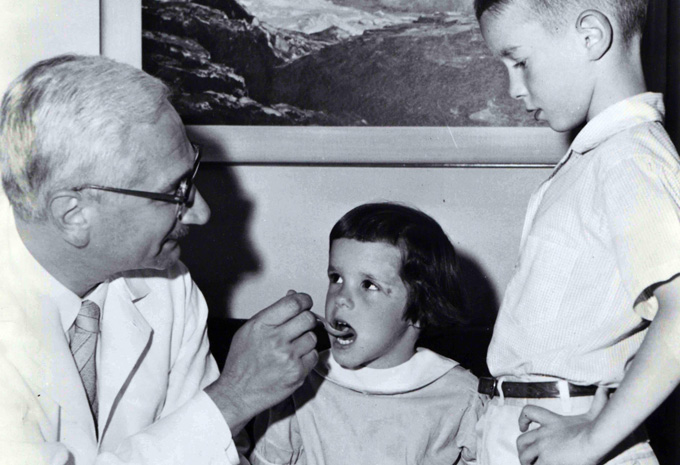

It was 1952 and polio was one of the most feared diseases in America, paralyzing more than 15,000 people, mostly children, each year. Parents wouldn’t let their children play outside, and quarantines were instituted in neighborhoods with polio cases.

Scientists were desperate for information about the virus, but many were hesitant to work with the infectious agent. “Everybody was afraid to go to that little lab in the basement,” says Martin Haas, professor of biology and oncology at the University of California, San Diego, and a personal friend and collaborator of Vogt’s for over three decades.

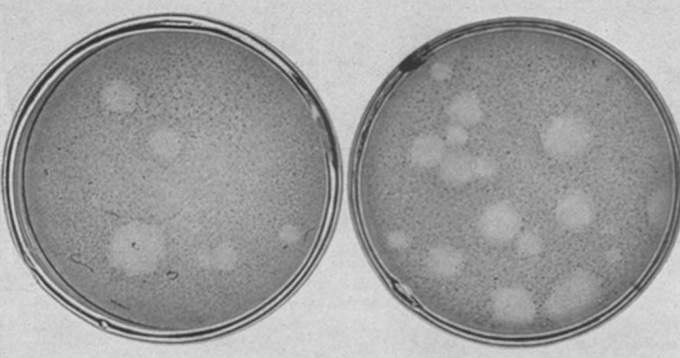

Vogt, a brand-new research associate in the laboratory of Renato Dulbecco, took on the task of attempting to grow and isolate the virus on a layer of monkey kidney cells. The method was called a plaque assay for the distinctive round plaques that form when a single virus particle kills all the cells around it.

Vogt didn’t tell her parents, both acclaimed scientists in Germany, that she was working with the virus. She later remarked that her father would have been very angry had he known of her poliovirus work, Haas says.

After a year of persistence, Vogt succeeded (and remained virus-free). In 1954, she and Dulbecco published the method for purifying and counting poliovirus particles. It was immediately used by other scientists to study variants of poliovirus, and by microbiologist Albert Sabin to identify and isolate strains of weakened poliovirus to make the oral polio vaccine used in mass vaccination campaigns around the world.

Perhaps even more importantly, the poliovirus plaque assay enabled scientists worldwide to analyze animal viruses at the level of individual cells, a field now known as molecular virology. Vogt and Dulbecco’s approach remains the gold standard for purifying and counting virus particles, including in recent studies of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The method, used to measure how infectious a virus is and isolate strains of a virus for further research, is ubiquitous in labs around the world.

Throughout a career spanning three-quarters of a century, beginning with a publication when she was 14 years old, Vogt contributed extensively to our knowledge of the genetics of animal development, how viruses can cause cancer and cellular life cycles. Upon her death in 2007 at the age of 94, nearly 100 three-ring binders lined the shelves of her office, filled with notes on decades of experiments.

Vogt was known for her intense, inventive lab work, including what others have called her “green thumb” for tissue culture — the process of growing cells, viruses and tissues in a dish.

“Being a meticulous person, she worried about every detail of the process of cell culture,” says David Baltimore, biologist and president emeritus of Caltech who worked for three years in a lab close to Dulbecco’s. “That’s really important, because it is finicky. Long experience and precise handling are key to getting good data.”

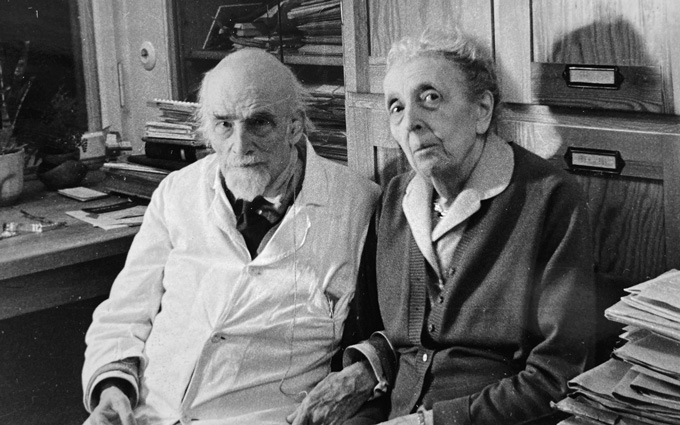

Born in 1913, Vogt grew up in Germany surrounded by science. The younger daughter of two pioneers of brain research, Oskar and Cécile Vogt, she and her sister Marthe were budding scientists from their youth. Marguerite Vogt’s first paper, published in 1927, investigated the genetics of fruit fly development.

But a year after receiving her M.D. at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in 1936, Vogt and her liberal family were ousted from Berlin by the Nazis. Her parents lost their positions at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research (now the Max Planck Institute), and Oskar was accused of supporting communists. The family avoided arrest or death due to the intercession of the Krupp family, former patients of Oskar’s and well-connected arms manufacturers who supplied the Nazi regime. With funding from the Krupps, Oskar and Cécile set up a private brain research institute in a remote part of Germany’s Black Forest. There, they continued their research and offered shelter and jobs to other people fleeing Nazi persecution.

From her parents’ institute in the Black Forest, Vogt published 39 seminal papers on how hormones and genetics influence the development of fruit flies, work that was later considered ahead of its time. In 1950, with the help of German-American scientists Hermann Muller and Max Delbrück, Vogt emigrated from Germany to the United States. Vogt rarely talked about her experiences during World War II. She never returned to Germany and refused to speak her native tongue with visiting German students and scientists.

After briefly working with Delbrück on bacterial genetics, Vogt went to work for Dulbecco on the poliovirus assay in 1952. After that success, the pair investigated the role of viruses in cancer. Once again, Vogt developed a technique to grow a virus — this time a small DNA-containing virus called polyomavirus — and the pair was able to count how many cells the virus transformed into cancer cells. In subsequent papers, the team demonstrated that certain viruses integrate their genetic material into host cell DNA, causing uncontrolled cell growth. The discovery changed the way scientists and doctors thought about cancer, showing that cancer is caused by genetic changes in a cell.

In 1963, Vogt followed Dulbecco to the Salk Institute in La Jolla, Calif. There, she spent decades studying viruses that can cause tumors, as well as other areas that sparked her interest, such as trying to define a cellular clock. “She was not only very intense, she was very inventive,” says Haas. “She always knew which way to go and what do to.”

Like the early days studying poliovirus, Vogt worked long and hard, typically six days a week, 10 hours per day. “She liked trying new things, so we often tried to do techniques that she had admired in papers she had read, or we learned things from other labs,” says Candy Haggblom, Vogt’s laboratory assistant for the last 30 years of Vogt’s career.

Vogt never married or had children. “Science was my milk,” she told the New York Times in 2001. But Vogt didn’t lack for company: She was a friend and mentor to many of the young scientists in the lab, four of whom went on to earn Nobel Prizes, and as an accomplished pianist and cellist, Vogt hosted a chamber music group that met at her home every Sunday morning for over 40 years, Haas says.

In 1975, Dulbecco was awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for work on how tumor viruses transform cells, a prize shared with Baltimore and virologist Howard Temin. Vogt was not recognized, and Dulbecco did not acknowledge her in his Nobel lecture.

During her lifetime, Vogt did not receive a single major prize or recognition. Despite an advanced degree and prestigious publication record, Vogt did not become a professor or get her own lab at Salk until after Dulbecco left the institute in 1972. She was 59 years old. That rankled her, says Haas, who cared for Vogt later in her life and thought of her like a mother. “She ran his lab while he ran around the world giving talks,” he says. “Marguerite ran it all.”

At 80, Vogt regularly jogged into the lab early in the morning. At 85, she published her final paper, fittingly about how human cells slow down and lose their ability to replicate with age.