This post was originally published on this site

In the late 1800s, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, a Spanish brain scientist, spent long hours in his attic drawing elaborate cells. His careful, solitary work helped reveal individual cells of the brain that together create wider networks. For those insights, Cajal received a Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1906.

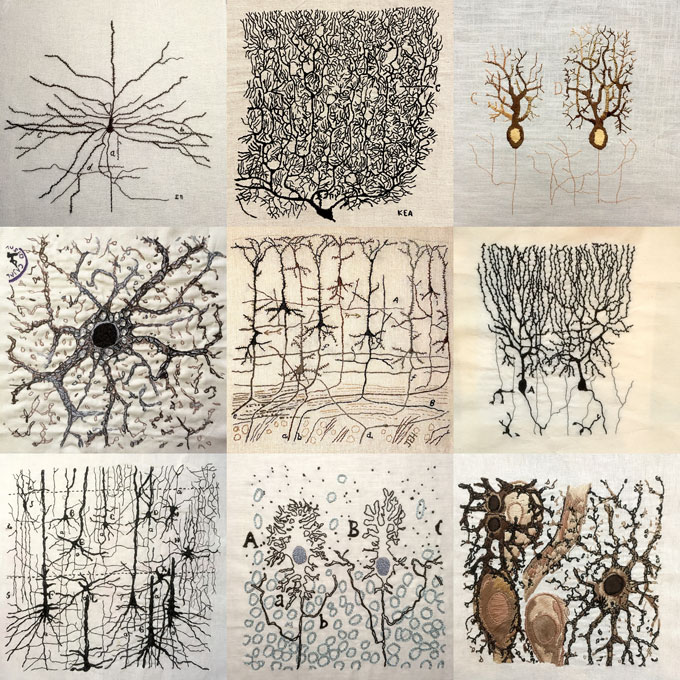

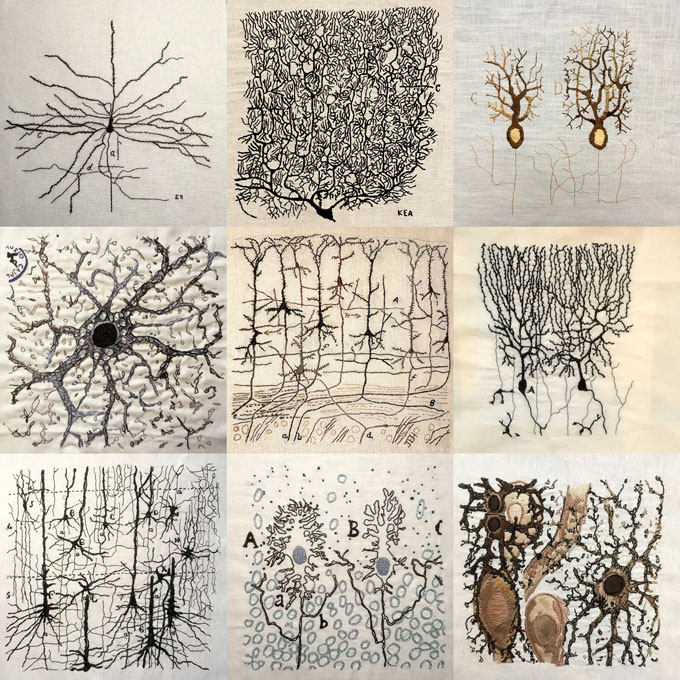

Now, a group of embroiderers has traced those iconic cell images with thread, paying tribute to the pioneering drawings that helped us see the brain clearly.

The Cajal Embroidery Project was launched in March of 2020 by scientists at the University of Edinburgh. Over a hundred volunteers — scientists, artists and embroiderers — sewed panels that will ultimately be stitched into a tapestry, a project described in the December Lancet Neurology.

Catherine Abbott, a neuroscientist at the University of Edinburgh, had the idea while talking with her colleague Jane Haley, who was planning an exhibit of Cajal’s drawings. These meticulous drawings re-created nerve cells, or neurons, and other types of brain cells, including support cells called astrocytes. “I said, off the cuff, ‘Wouldn’t it be lovely to embroider some of them?’”

The project had just begun when the COVID-19 pandemic upended the world. But stitching at home amid the shutdowns was a soothing activity, says Katie Askew, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Edinburgh. “Having something that can occupy your hands so you’re not scrolling through your phone looking at the news is great,” she says. Askew chose to re-create a type of neuron known as a Purkinje cell from a human cerebellum, a structure at the back and bottom of the brain that helps coordinate movement. Purkinje cells collect signals with lush thickets of tendrils, before sending along their own quieting signals. Cajal’s particular specimen nearly filled Askew’s fabric panel. “They are amazing cells,” she says. Spending months staring at a single cell has led her to spot similar branches in trees, she says.

Cajal’s artistic eye is obvious in his drawings, says Annie Campbell, one of the volunteers who contributed a square. “His images live in this liminal space between science and fine art,” says Campbell, who is herself an artist at Auburn University in Alabama. “He was making aesthetic decisions about what to leave out so that somebody could look at that and say, ‘Oh, that’s a neuron without all its dendrites so I can see the astrocyte wrapped around it.’”

Campbell decided to embroider an astrocyte with looping tendrils “for the beauty of the shape,” she says. As she sewed, she also began to learn more about the cells, which perform a variety of crucial jobs in the brain, including healing injuries.

Cajal’s drawings are still relevant today, says Abbott. “What strikes me the most is how completely timeless they are.” Even with powerful, high-resolution microscopes, scientists today see cells in a similar way. “It’s almost depressing to think that even with all of this fancy equipment, we’re not all that far ahead,” she says. “But I like that. I like that there is this direct connection to 100 years ago.”

That thread ties the embroiderers today to Cajal’s work, Abbott says. “We are looking at the same thing and feeling the same sense of wonder.”