This post was originally published on this site

In fall 2021, staffers at Johnson Memorial Health were hoping they could finally catch their breath. They were just coming out of a weeks-long surge of covid-19 hospitalizations and deaths, fueled by the delta variant.

But on Oct. 1 at 3 a.m., a Friday, the hospital CEO’s phone rang with an urgent call.

“My chief of nursing said, ‘Well, it looks like we got hacked,’” said David Dunkle, CEO of the health system based in Franklin, Indiana.

The information technology team at Johnson Memorial discovered a ransomware group had infiltrated the health system’s networks. The hackers left a ransom note on every server, demanding the hospital pay $3 million in bitcoin within a few days.

The note was signed by the “Hive,” a prominent ransomware group that has targeted more than 1,500 hospitals, school districts, and financial firms in over 80 countries, according to the Justice Department.

Johnson Memorial was just one victim in a rising wave of cyberattacks on U.S. hospitals. One study found that cyberattacks on the nation’s health care facilities more than doubled from 2016 to 2021 — from 43 attacks to 91.

In the aftermath of a breach, the focus frequently falls on the risk of confidential patient information being exposed, but these attacks can also leave hospitals hemorrhaging millions of dollars in the months that follow, and also cause disruptions to patient care, potentially putting lives at stake.

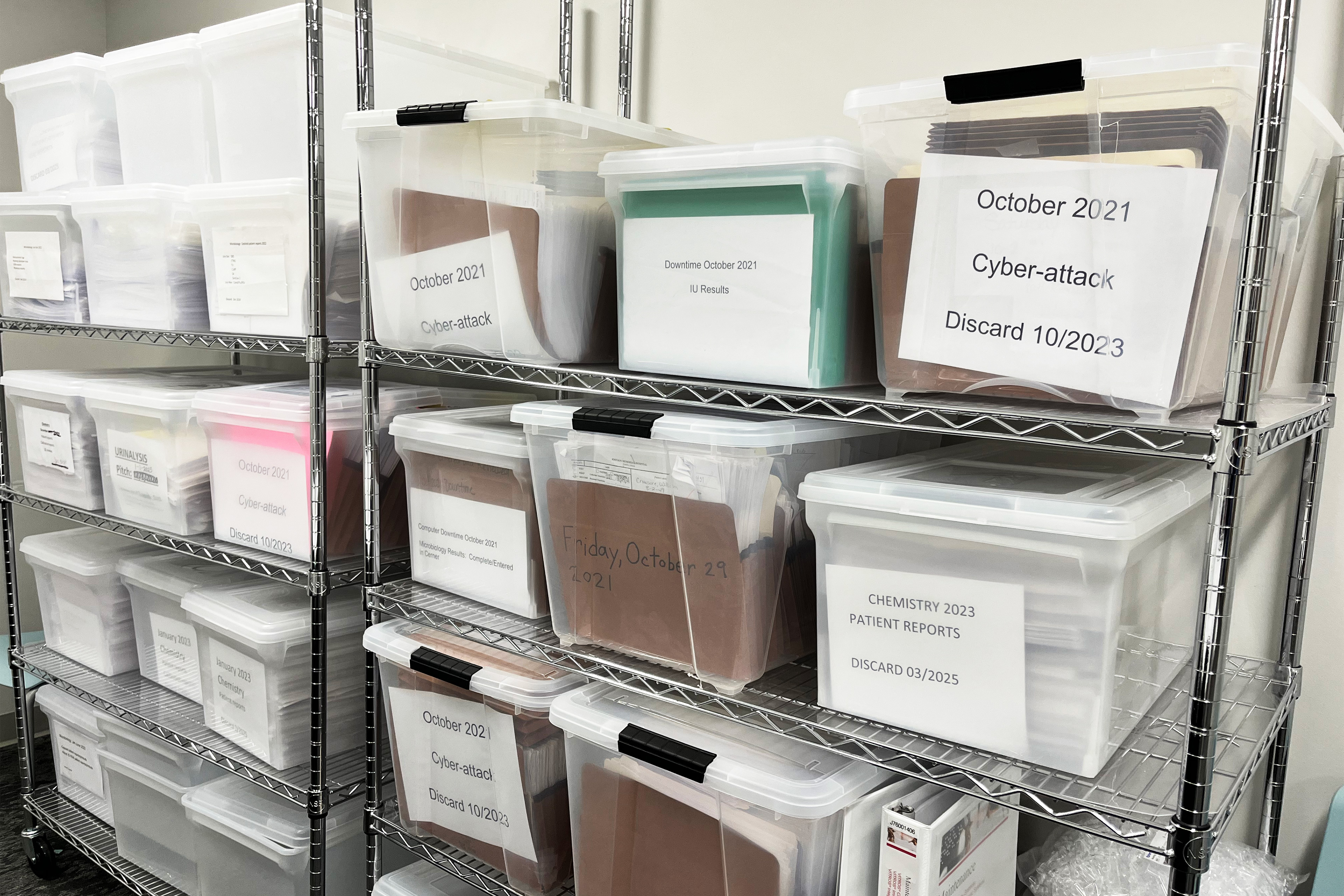

After its own attack, the staff at Johnson Memorial suddenly had to revert to low-tech ways of patient care. They relied on pen and paper for medical records and notes, and sent runners between departments to take orders and deliver test results.

A few hours after that 3 a.m. call, Dunkle was on the phone with cybersecurity experts and the FBI.

The burning question on his mind: Should his hospital pay the $3 million ransom to minimize disruptions to its operations and patient care?

Dunkle worried about potential fines levied by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control against the hospital if it paid a ransom to an unknown entity that turned out to be on a sanctions list.

Dunkle also worried about possible lawsuits, because the hackers claimed they stole sensitive patient information they’d release to the “dark web” if Johnson Memorial did not pay up. Other health data breaches have led to class-action lawsuits from patients.

The Office for Civil Rights, within the Department of Health and Human Services, can also impose financial penalties against hospitals if patient data protected by federal privacy laws is divulged.

“It was information overload,” Dunkle recalled. All the while, he had a hospital full of patients needing care and employees wondering what to do.

In the end, the hospital did not pay the ransom. Leaders decided to disconnect after the attack, assess, and then rebuild, which meant taking several critical systems offline. That upended normal operations in various departments.

The emergency department diverted ambulances with sick patients to other hospitals because the staff couldn’t access patients’ medical records. In the obstetrics unit, newborns usually wear security bracelets around their tiny legs to prevent unauthorized adults from moving the infant or leaving the unit with them. When that tracking system went dark, staff members physically guarded the unit doors.

During one delivery, nurses struggled to communicate with an Afghan refugee who came from the nearby military post to give birth. The remote translation service they typically used was inaccessible because of the cyberattack.

“Stressed-out nurses were using Google Translate to communicate with this woman in labor,” said Stacey Hummel, the maternity department manager. “It was crazy.”

Hummel said it was the hardest challenge she’s ever faced in her 24 years of experience — even worse than the covid-19 pandemic. As the cyberattack unfolded, her nursing team was praying, “Please don’t let the fetal monitors go down.”

And then they did.

The clinical staff suddenly could no longer receive digital notifications outside the labor rooms, notifications that help them monitor the vital signs of laboring women and their fetuses. That meant critical data points, like a dangerously low heart rate or high blood pressure, could go unnoticed.

“Once that happened, we had to station a nurse in every single room,” Hummel said. “So staffing was a nightmare because you had to stand there and watch the monitor.”

The hospital’s billing department was also crippled. For months afterward, they were unable to bill insurance plans to be paid in a timely fashion. An IBM report estimated that cyberattacks on hospitals cost an average of nearly $10 million per incident, excluding any ransom payment — the highest among all industries. Hospital leaders say that, for this reason, cyberattacks pose an existential threat to the viability of hospitals across the country.

Cyber insurance has become a critical part of hospital budgets, according to John Riggi, national adviser for cybersecurity and risk at the American Hospital Association.

But some institutions are finding the insurance coverage isn’t comprehensive, so even after an attack they remain on the hook for millions of dollars in damages. At the same time, insurance premiums can soar after a cyberattack.

“The government certainly could help in the space of cyber insurance, perhaps setting up a national cyber insurance fund, just like post-9/11, when folks could not obtain insurance against terrorist attacks, to help with that emergency financial aid,” Riggi said.

The federal government has taken steps to address the threat of cyberattacks against critical infrastructure, including training and awareness campaigns by the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. The FBI has taken down several ransomware groups, including the Hive, the group behind the attack on Johnson Memorial.

Today, Johnson Memorial is up and running again. But it took nearly six months to resume near-normal operations, according to the hospital’s chief operating officer, Rick Kester.

“We worked … every single day in October, every single day. And some days, 12, 14 hours,” Kester said.

The hospital is still dealing with some ongoing costs. Its revenue cycle has not fully recovered and its cyberattack insurance claim, submitted nearly two years ago, still hasn’t been paid, Dunkle said. The hospital’s annual insurance premium is up 60% since the incident.

“That is an incredible increase in cost over the last three or four years and … when your claims aren’t paid, it can be even more frustrating,” he said. “We are investing so much in cybersecurity right now that I don’t know how small hospitals will be able to afford [to operate] much longer.”

And this week, a hospital in Illinois may become the first to close down partly due to a cyberattack. St. Margaret’s Health in Spring Valley, Illinois, planned to close its doors June 16. Suzanne Stahl, chair of the hospital’s parent company, SMP Health, said it became impossible to continue the hospital’s operations “due to a number of factors, such as the covid-19 pandemic, the cyberattack on the computer system of St. Margaret’s Health, and a shortage of staff.”

The hospital suffered a ransomware attack in 2021 that left it unable to bill insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare for more than three months, according to Linda Burt, the hospital’s vice president of quality and community services. Burt said not being able to submit claims put the hospital in a “financial spiral.”

This article is from a partnership that includes Side Effects Public Media, NPR, and KFF Health News.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.