This post was originally published on this site

NEW ORLEANS — Erin Brown recalls all too well the dreadful call he received from his mother in 2021, while in the thralls of the covid-19 pandemic: His cousin — his “brother” — had been shot six times.

Although it was not the first time gun violence had reached the then-17-year-old Brown’s social circle, that incident was different. It involved family. So it hit Brown harder, even though his cousin, then 21, survived the gunshot wounds.

Now, while Brown works toward high school graduation and a career in graphic design, he said, he stays indoors in his neighborhood, the Lower 9th Ward. The frequent accidental shootings there frighten him the most. The gunfire outside his windows makes it hard to sleep.

“We were all just quarantined, now we can’t even go outside,” said Thomas Turner, 17, Brown’s classmate at the campus of the NET: Gentilly charter school, in New Orleans’ Gentilly neighborhood. “Just because you want to shoot and stuff, I feel like that is just locking us back in our room.”

It’s an all-too-common feeling in pockets of this city — which had one of the nation’s highest rates of homicides among large cities in 2022 — and other communities across the country where shots ring out regularly. As gun violence soars nationwide, children’s health experts are advocating for such traumatic exposure to be considered what’s known as an “adverse childhood experience.”

For decades, the definition for these adverse childhood events has excluded exposure to community gun violence. That means young people exposed to shootings outside the home have been without access to the broad range of intervention efforts and support at various stages of life given to youth facing other forms of traumatic events, such as child abuse or household dysfunction, said Nina Agrawal, a pediatrician who has researched how such experiences have been handled.

“We need to start recognizing that our children are experiencing trauma and it may not show up overtly, but we have to start recognizing it and listening,” said Agrawal, who chairs the Gun Safety Committee for the New York state chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Agrawal’s young patients who have witnessed the effects of gun violence are developing chest pain, headaches, and other health concerns, a commonality among youth experiencing a lack of sleep due to gun violence paranoia, she said. The more time a child spends on high alert, the more disruptions to the immune system and brain function occur, as well as effects on mental and behavioral health, said Agrawal.

For Turner, it was the day of his grandmother’s funeral in 2021 that brought gun violence too close to home. As young children and older relatives gathered to honor her life in the Holly Grove neighborhood, shots were fired outside the church.

Turner recalled how his first instinct was to find his younger sister and mother, who were also attending the funeral. Although he is relieved that the suspect in the shooting was arrested — something locals complain is rare — Turner said he now feels as if he’s susceptible to such capricious violence while living in New Orleans.

Gun injuries, including suicides, are the leading cause of death for children and teens nationwide. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not differentiate which injuries come from stray bullets, and electronic health records don’t typically record how patients feel about their safety. So Agrawal regularly asks her patients if they feel safe at home, school, and other places.

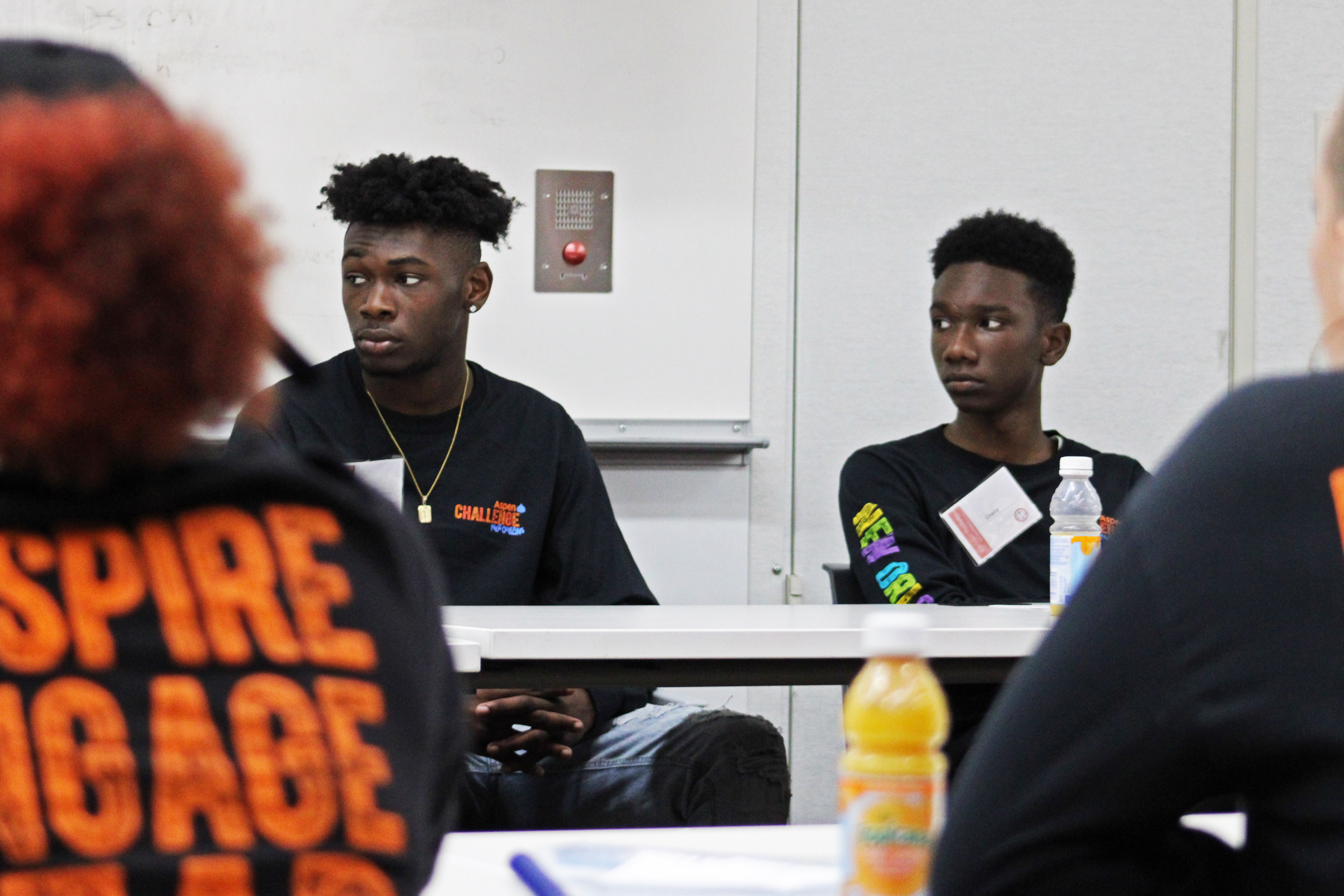

Brown and Turner are aware of the ever-present risk, so they channel their energy into the classroom, where they recently competed, with a small group of fellow NET students, in the national Aspen Challenge, aiming to pinpoint societal solutions to curb the epidemic of gun violence and reduce the damage it causes to mental health. The group, Heal NOLA, recommended coping mechanisms such as creating artwork and encouraging anonymous story-sharing of the mental trauma through social media. They also said the normalization of gun violence needs to end.

Before debuting their proposals in competition, Turner and classmate Chainy Smith spoke at a city-sponsored public safety summit in early April about how the internet and social media further the culture of gun ownership as self-defense. They advocated for a cultural shift in which flaunting one’s gun doesn’t earn respect and popularity.

For them, mental health resources are available inside the halls of the NET, the students said, and the intimate classroom where they work on the Aspen Challenge feels like a safe space for emotional processing. But Turner, Brown, and their other classmates know that isn’t always the reality elsewhere — outside of school, they said, they’ve been told by family and other adults that they are too young to understand depression.

Terra Jerome, a student participating in the Aspen project, said that when she has spoken out about mental health she feels as if no one understands where she is coming from. “Like, you’re not getting what I’m saying,” she said.

And the veneer of safety disappears when they leave school each day.

During spring break, two students from the school died in separate shootings.

“New Orleans is very traumatized,” said Erin Barnard, the Heal NOLA faculty adviser. “Everybody seems to know that everyone’s traumatized, but then, what are we doing to get out of that?”

Brown and Turner each worry about what lies beyond for them — and for their mothers — when they leave home. Both are close to their moms. They can talk openly about mental health with them, something they realize isn’t the case for every kid.

This element of being heard is a crucial intervention, Agrawal said. She said medical research needs to further understand the effects of youth isolation, adding that she has seen how it leads to increased rates of mental health problems, from intergenerational trauma to suicidal ideation. The younger children are when exposed to gun violence, she said, the higher their susceptibility to post-traumatic stress disorder. She is advocating for intervention for children under age 5 and before they’re exposed to gun violence.

Rather than feel the all-too-common urge of retaliation, Turner and Brown reflect on the incidents from a mental health perspective, wondering what was going on in the heads of the individuals who carried out the shootings.

“It all leads back to mental health, because why is that person carrying a gun in the first place?” Turner said.

Turner said he sees things he shouldn’t have by age 17. But he said his fear may not always be visible to others when he is on the basketball court, in the gym, or at the Uptown pizza spot that employs him. He’s just trying to live his life, he said. He hopes to become a firefighter and, someday, have kids. He said he doesn’t want them to endure such mental trauma.

For now, Turner feels it is his role to get the word out that young people are hurting mentally.

“If somebody need a hug, just a hug, I don’t have to know you, I’ll give you a hug,” said Turner. “You want to talk to me and tell me anything? I’m going to sit here and listen, because I’d want someone to do that for me.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.