This post was originally published on this site

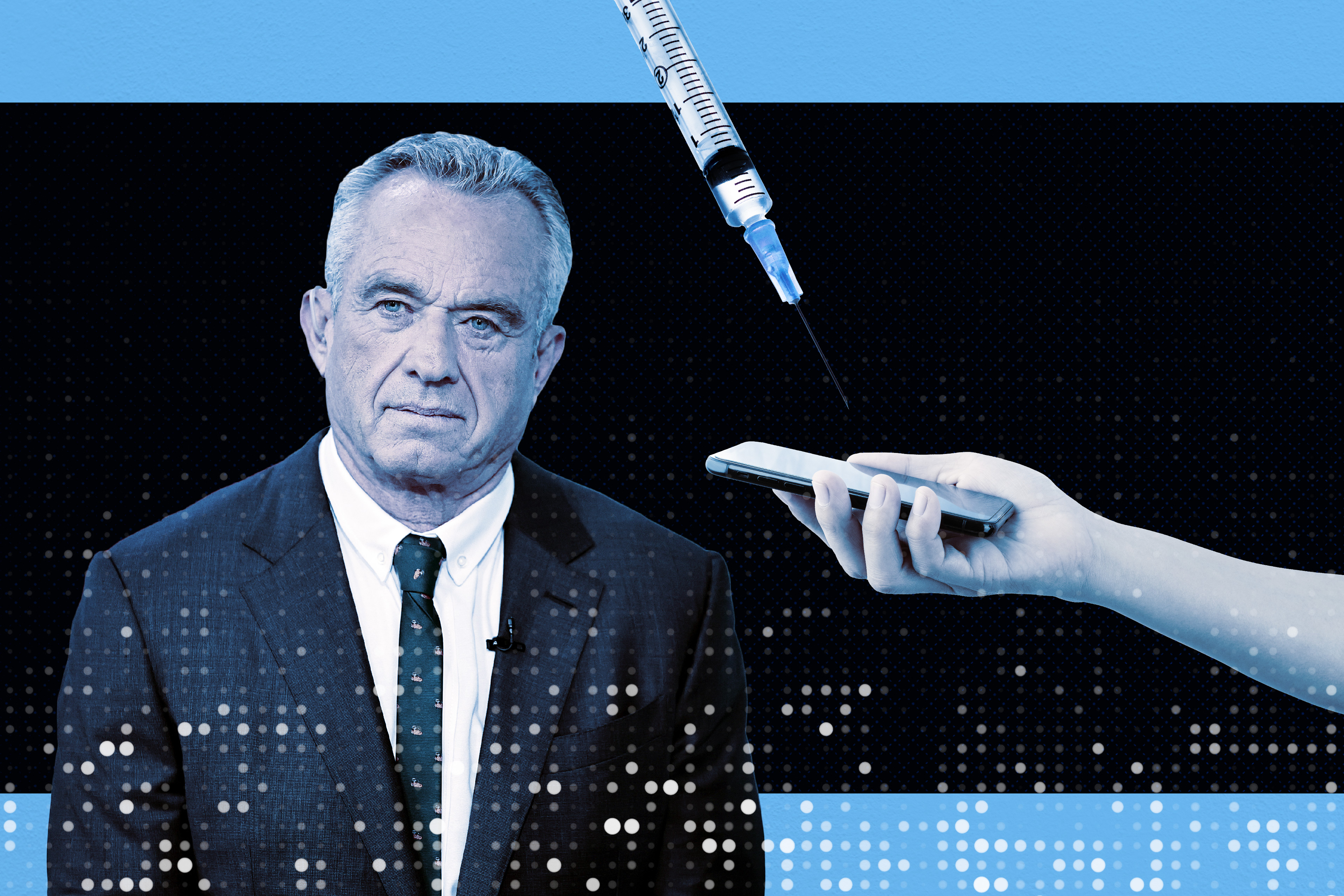

Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the latest scion of the Kennedy clan to seek the presidency, has a set of unusual fans: some of the most influential tech executives and investors in America. Kennedy’s strong anti-vaccine views are, for this group, a sideshow.

“Tearing down all these institutions of power. It gives me glee,” said one of his boosters in tech, Chamath Palihapitiya, a garrulous former Facebook executive, nearly two hours into a May episode of the popular “All-In” podcast he co-hosts with other tech luminaries. The person who might help with the demolition was the show’s guest, Kennedy himself.

“Me too,” responded David Sacks, Palihapitiya’s co-host on the podcast, an early investor in Facebook and Uber. Sacks and Palihapitiya said they would host a fundraiser for Kennedy, which, according to the Puck news outlet, was set for June 15.

Kennedy’s newfound friends in Silicon Valley were mostly loud supporters of vaccines early in the pandemic, but they have proven more than willing to let him expound on his anti-vaccine views and conspiracy theories as he promotes his presidential bid. During a two-hour forum on Twitter, hosted by company owner Elon Musk and Sacks, Kennedy raised a range of themes, but returned to the subject he’s become famous for in recent years: his skepticism about vaccines and the pharmaceutical companies that sell them.

Indeed, on the June 5 appearance, he praised Musk for ending “censorship” on his corner of social media. A promoter of conspiracy theories, Kennedy said various forces are keeping him from discussing his safety concerns over vaccines, like Democratic Rep. Adam Schiff (as part of the intelligence apparatus), Big Pharma, and Roger Ailes (who has been dead for six years).

Kennedy argued an influx of direct-to-consumer advertising from pharmaceutical concerns keep media outlets, like Fox News, from featuring his theories about vaccine safety. Fox didn’t respond to a request for comment.

He then said he supported reversing policies that allow direct-to-consumer ads in media. (Kennedy earlier dubbed himself a “free-speech absolutist” and, later, in a discussion about nuclear power, a “free-market absolutist” and even later a “constitutional absolutist.” Legal scholars doubt the courts, on First Amendment grounds, would be receptive to a ban of direct-to-consumer ads.)

Support for Kennedy in the venture capital and tech communities, which have a big financial stake in the advancement of science and generally reject irrational conspiracy theories, is likely limited. Multiple venture capitalists and technologists contacted by KFF Health News expressed puzzlement over what’s driving the embrace from Musk and others.

“I think he is a lower-intellect, Democratic version of Donald Trump, so he attracts libertarian-leaning, anti-‘woke,’ socially liberal folks as a protest vote,” said Robert Nelsen, a biotech investor with Arch Venture Partners. “I think he is a dangerous conspiracy theorist, who has contributed to many deaths with his anti-vaccine lies.”

But the ones with the megaphones are letting Kennedy talk. Jason Calacanis, another co-host of “All-In” and a pal of Musk’s, said late in the podcast he was pleased the conversation didn’t lead with “sensational” topics — like vaccines. Still, during the podcast, Kennedy was given nearly five uninterrupted minutes to describe his views on shots — a long list of alleged safety problems, ranging from allergies, autism, to autoimmune problems, many of which have been discredited by reputable scientists.

David Friedberg, another Silicon Valley executive and guest on the show, suggested there wasn’t “direct evidence” for those problems. “I don’t think it’s solely the vaccines,” Kennedy conceded. After an interlude touching on the role of chemicals, he was back to injuries caused by diphtheria shots.

While Friedberg, a former Google executive and founder of an agriculture startup sold to Monsanto for a reported $1.1 billion, pushed back against Kennedy, he did so deep into the podcast, after the candidate had left. Kennedy’s views — on nuclear power and vaccines — manifest “as conspiracy theories,” he said. “It doesn’t resonate with me,” he continued, as he “likes to have empirical truth be demonstrated.”

The muted pushback is a bit of a reversal. Early in the rollout of covid-19 vaccines, many tech luminaries had been among the most loudly pro-shot individuals. The “All-In” crew was no exception. Sacks once tweeted, “We’ve got to raise the bar for what we expect from government”; Palihapitiya begged administrators to “stop virtue signaling” with vaccination criteria and simply mass-vaccinate instead.

That was then. Sacks recently retweeted a video of Bill Gates questioning the effectiveness of current covid vaccines and defended Kennedy from charges of being anti-vaccination.

Musk himself has sometimes suggested he has qualms with vaccines, tweeting in January, without evidence, that “I’m pro vaccines in general, but there’s a point where the cure/vaccine is potentially worse, if administered to the whole population, than the disease.”

Musk isn’t the only top tech executive to signal interest in Kennedy’s candidacy. Block CEO and Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey has tweeted Kennedy “can and will” win the presidency.

In some ways, the Valley’s interest in Kennedy — vaccine skepticism and all — has deep roots. Tech culture grew out of Bay Area counterculture. It has historically embraced individualistic theories of health and wellness. While most have conventional views on health, techies have dabbled in “nootropics,” supplements that purportedly boost mental performance, plus fad diets, microdosing psychedelics, and even quests for immortality.

There’s a “deeply held anti-establishment ethos” among many tech leaders, said University of Washington historian Margaret O’Mara. There’s a “suspicion of authority, disdain for gatekeepers and traditionalists, dislike of bureaucracies of all kinds. This too has its roots in the counterculture era, and the 1960s antiwar movement, in particular.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.