This post was originally published on this site

Marijuana and other products containing THC, the plant’s main psychoactive ingredient, have grown more potent and more dangerous as legalization has made them more widely available.

Although decades ago the THC content of weed was commonly less than 1.5%, some products on the market today are more than 90% THC.

The buzz of yesteryear has given way to something more alarming. Marijuana-related medical emergencies have landed hundreds of thousands of people in the hospital and millions are dealing with psychological disorders linked to cannabis use, according to federal research.

But regulators have failed to keep up.

Among states that allow the sale and use of marijuana and its derivatives, consumer protections are spotty.

“In many states the products come with a warning label and potentially no other activity by regulators,” said Cassin Coleman, vice chair of the scientific advisory committee of the National Cannabis Industry Association.

The federal government has generally taken a hands-off approach. It still bans marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance — as a drug with no accepted medical use and a high chance of abuse — under the Controlled Substances Act. But when it comes to cannabis sales, which many states have legalized, the federal government does not regulate attributes like purity or potency.

The FDA “has basically sat on its hands and failed to honor its duty to protect the public health,” said Eric Lindblom, a scholar at Georgetown University’s law school who previously worked at the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

Pot has changed profoundly since generations of Americans were first exposed to it.

Cannabis has been cultivated to deliver much higher doses of THC. In 1980, the THC content of confiscated marijuana was less than 1.5%. Today many varieties of cannabis flower — plant matter that can be smoked in a joint — are listed as more than 30% THC.

At one California dispensary, the menu recently included a strain posted as 41% THC.

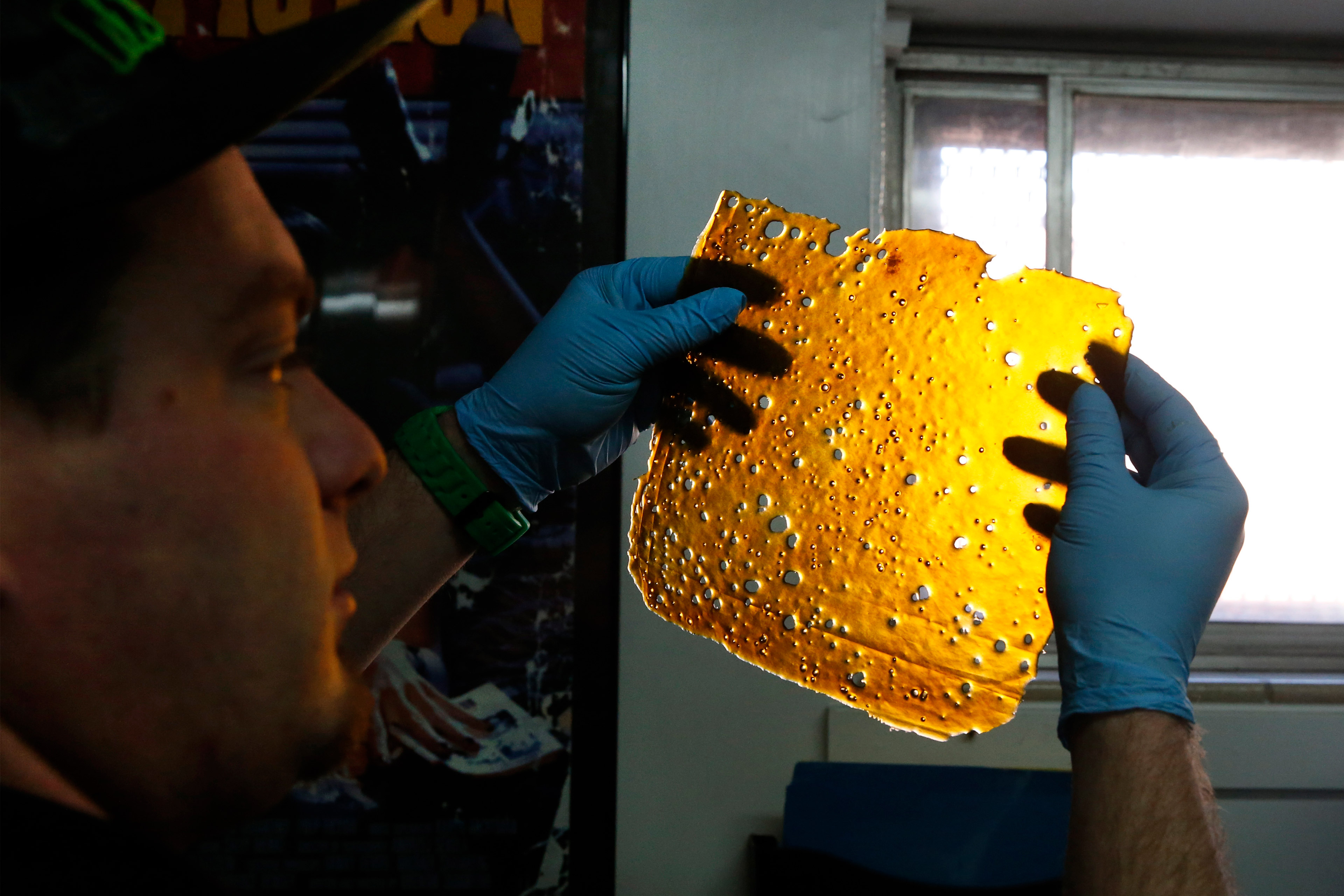

Legalization has also helped open the door to products that are extracted from marijuana but look nothing like it: oily, waxy, or crystalline THC concentrates that are heated and inhaled through vaping or dabbing, which can involve a bong-like device and a blowtorch.

Today’s concentrates can be more than 90% THC. Some are billed as almost pure THC.

Few people personify the mainstreaming of marijuana as vividly as John Boehner, the former U.S. House speaker. The Ohio Republican long opposed marijuana and, in 2011, reportedly declared himself “unalterably opposed” to its legalization.

Now he’s on the board of Acreage Holdings, a producer of marijuana products.

And Acreage Holdings illustrates the evolution of the industry. Its Superflux brand markets a vaping product — “pure live resin in a convenient, instant format” — and concentrates such as “budder,” “sugar,” “shatter,” and “wax.” The company bills its “THCa crystalline” concentrate as the “ultimate in potency.”

Higher concentrations pose greater hazards, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “The risks of physical dependence and addiction increase with exposure to high concentrations of THC, and higher doses of THC are more likely to produce anxiety, agitation, paranoia, and psychosis,” its website said.

In 2021, 16.3 million people in the United States — 5.8% of people 12 or older — had experienced a marijuana use disorder within the past year, according to a survey published in January by the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

That was far more than the combined total found to have substance use disorders involving cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, prescription stimulants such as Adderall, or prescription pain relievers such as fentanyl and OxyContin.

Other drugs are more dangerous than marijuana, and most of the people with a marijuana use disorder had a mild case. But about 1 in 7 — more than 2.6 million people — had a severe case, the federal survey found.

Most clinicians equate the term “severe use disorder” with addiction, said Wilson Compton, deputy director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Cannabis use disorder “can be devastating,” said Smita Das, a Stanford psychiatrist and chair of an American Psychiatric Association council on addiction.

Das said she has seen lives upended by cannabis — very successful people who have lost families and jobs. “They’re in a place where they don’t know how they got there because it was just a joint, it was just cannabis, cannabis wasn’t supposed to be addictive for them,” Das said.

Medical diagnoses attributed to marijuana include “cannabis dependence with psychotic disorder with delusions” and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, a form of persistent vomiting.

An estimated 800,000 people made marijuana-related emergency department visits in 2021, according to a government study published in December 2022.

‘Go Directly’ to Detox

A Colorado father thought it was just a matter of time before cannabis killed his son.

In spring 2021, the teen ran a red light, crashed into another car — injuring himself and the other driver — and fled the scene, the father recalled in interviews.

In the wreckage, the father later found joints, empty containers of a high-potency THC concentrate known as wax, and a THC vape pen.

On his son’s cellphone, he found text messages and scores of references to dabbing and weed. The teen said he had been dabbing before the crash and had intended to kill himself.

Weeks later, police arranged for him to be held involuntarily at a hospital for psychiatric evaluation. According to a police report, he thought cartel snipers were after him.

The doctor who evaluated the teen diagnosed “cannabis abuse.”

“Stop doing dabs or wax as they can make you extremely paranoid,” the doctor wrote. “Go directly to the detox program of your choice.”

By the father’s account, over the past two years the teen logged several other involuntary holds, dozens of encounters with police, repeated jailings, and a series of stays in inpatient treatment facilities.

At times out of touch with reality, he texted that God spoke to him and gave him superpowers.

The damage was also financial. Health insurance claims for his treatment totaled nearly $600,000, and the family’s out-of-pocket expenses came to almost $40,000 as of February.

In interviews for this article, the father spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid undermining the son’s recovery.

The father is convinced that his son’s mental illness was a result and not a cause of the drug use. He said the symptoms receded when his son stopped using THC and returned when he resumed.

His son is now 20, off marijuana, and doing well, the father said, adding, “I have absolutely no doubt in my mind that cannabis use is what caused his psychosis, delusions, and paranoia.”

Uneven State Regulation

Medical use of marijuana is now legal in 40 states and the District of Columbia, and recreational or adult use is legal in 22 states plus D.C., according to MJBizDaily, a trade publication.

Early in the covid-19 pandemic, while much of America was in lockdown, marijuana dispensaries delivered. Many states declared them essential businesses.

But only two adult-use states, Vermont and Connecticut, have placed caps on THC content — 30% for cannabis flower and 60% for THC concentrates — and they exempt pre-filled vape cartridges from the caps, said Gillian Schauer from the Cannabis Regulators Association, a group of state regulators.

Some states cap the number of ounces or grams consumers are allowed to buy. However, even a little marijuana can amount to a lot of THC, said Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, a professor of health policy, economics, and law at the University of Southern California.

Some states allow only medical use of low-THC products — for instance, in Texas, substances that contain no more than 0.5% THC by weight. And some states require warning labels. In New Jersey, cannabis products composed of more than 40% THC must declare: “This is a high potency product and may increase your risk for psychosis.”

Colorado’s marijuana rules run more than 500 pages. Yet its disclosure underscores the limits of consumer protections: “This product was produced without regulatory oversight for health, safety, or efficacy.”

Figuring out the right rules may not be simple. For example, warning labels could shield the marijuana industry from liability, much as they did for tobacco companies for many years. Capping potency could limit options for people who take high doses for relief from medical problems.

Overall, at the state level, the cannabis industry has blunted regulatory efforts by arguing that onerous rules would make it hard for legitimate cannabis businesses to compete with illicit ones, Pacula said.

Pacula and fellow researchers have called for the federal government to step in.

Months after ending his term as FDA commissioner, Scott Gottlieb issued a similar plea.

Complaining that states had gotten “far down the field while the feds sat on the sidelines,” Gottlieb called for “a uniform national scheme for THC that protects consumers.”

That was in 2019 and little has changed since then.

Where’s the FDA?

The FDA oversees food, prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, and medical devices. It regulates tobacco, nicotine, and nicotine vapes. It oversees tobacco warning labels. In the interest of public health and safety, it also regulates botanicals, medical products that can include plant material.

Yet, when it comes to the marijuana that people smoke, the cannabis-derived THC concentrates they vape or dab, and edibles infused with THC, the FDA appears very much on the sidelines.

The medical marijuana sold at dispensaries is not FDA-approved. The agency hasn’t vouched for its safety or efficacy or determined the proper dosage. It doesn’t inspect the facilities where the goods are produced, and it doesn’t assess quality control.

The agency does invite manufacturers to put cannabis products through clinical trials and its drug approval process.

The FDA’s website notes that THC is the active ingredient in two FDA-approved drugs used in cancer treatment. That alone apparently places the substance under FDA jurisdiction.

The FDA has “all the power it needs to regulate state-legalized cannabis products much more effectively,” said Lindblom, the former FDA official.

At least publicly, the FDA has focused not on THC concentrates derived from cannabis or weed smoked in joints, but rather on other substances: a THC variant derived from hemp, which the federal government has legalized, and a different cannabis derivative called cannabidiol or CBD, which has been marketed as therapeutic.

“The FDA is committed to monitoring the marketplace, identifying cannabis products that pose risks, and acting, within our authorities, to protect the public,” FDA spokesperson Courtney Rhodes said.

“Many/most THC products meet the definition of marijuana, which is a controlled substance. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) regulates marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act. We refer you to the Drug Enforcement Administration for questions about regulation and enforcement under the provisions of the CSA,” Rhodes wrote in an email.

The DEA, part of the Justice Department, did not respond to questions for this article.

As for Congress, perhaps its most consequential step has been limiting enforcement of the federal prohibition.

“Thus far, the federal response to state actions to legalize marijuana has largely been to allow states to implement their own laws on the drug,” a 2022 Congressional Research Service report said.

In October, President Joe Biden directed the secretary of Health and Human Services and the attorney general to review the federal government’s stance toward marijuana — whether it should remain classified among the most dangerous and tightly controlled substances.

In December, Biden signed a bill expanding research access to marijuana and requiring federal agencies to study its effects. The law gave agencies a year to issue findings.

Some marijuana advocates say the federal government could play a more constructive role.

“NORML does not opine that cannabis is innocuous, but opines that its potential risks are best mitigated via legalization, regulation, and public education,” said Paul Armentano, deputy director of the group formerly known as the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

“Products have to be tested for purity and potency,” he said, and “the federal government could have some oversight in licensing the labs that test those products.”

In the meantime, said Coleman, adviser to the National Cannabis Industry Association, states are left “having to become USDA + FDA + DEA all at the same time.”

And where does that leave consumers? Some, like Wendy E., a retired small-business owner in her 60s, struggle with the effects of today’s marijuana.

Wendy, who spoke on the condition that she not be fully named, started smoking marijuana in high school in the 1970s and made it part of her lifestyle for decades.

Then when her state legalized it, she bought it in dispensaries “and very quickly noticed that the potency was much higher than what I had traditionally used,” she said. “It seemed to have exponentially increased.”

In 2020, she said, the legal marijuana — much stronger than the illicit weed of her youth — left her obsessing about ways to kill herself.

Once, the self-described “earth-mother hippie” found camaraderie passing a joint with friends. Now, she attends Marijuana Anonymous meetings with others recovering from addiction to the stuff.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.