This post was originally published on this site

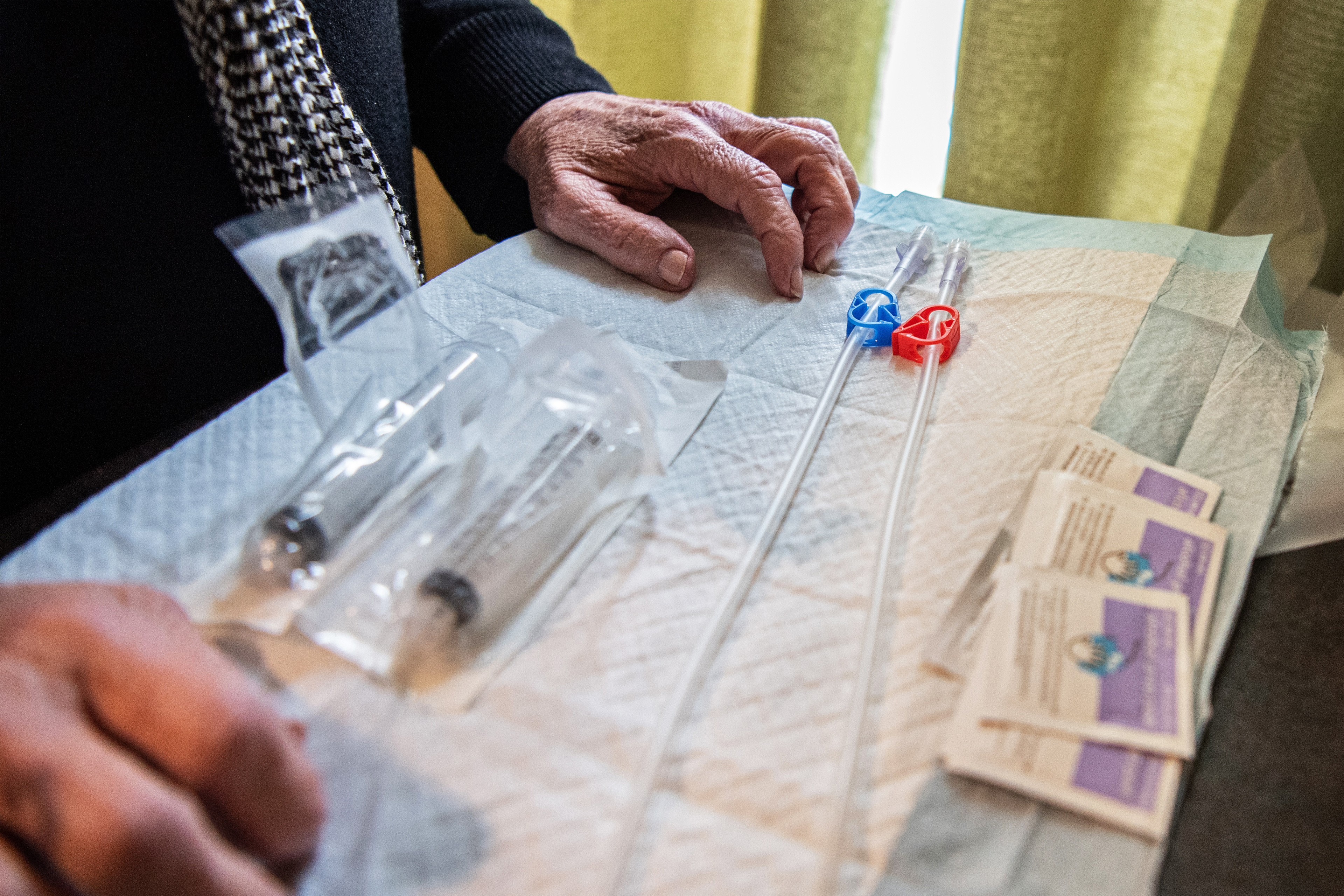

Nieltje Gedney was half-asleep in her West Virginia home, watching murder mysteries over the hum of a bedside hemodialysis machine, when she felt something warm and wet in her armpit.

A needle inserted into her arm had fallen loose, breaking a circuit that the machine used to clean her blood. It was still pumping, drawing and filtering blood as designed, but the blood was now spilling into her bed instead of returning to her body.

Gedney, a leader of the Home Dialyzors United support group, knew what to do. Armed with a decade of experience with hemodialysis, she calmly applied pressure to her arm and pressed a red button that turned off the pump. Her blood loss stopped. In the seconds her needle was loose, Gedney’s blood had soaked through her pajamas, bedsheets, and quilt.

“I sat up and looked down, and I was literally covered in blood,” said Gedney, 71. “It was a bloodbath.”

On that frightful night last year, Gedney survived a rare and very dangerous complication of hemodialysis — a venous needle dislodgment, or VND. About 500,000 Americans with kidney failure rely on hemodialysis to mimic the function of healthy kidneys by pumping their blood through an external cleaning machine. If the venous needle dislodges, the machine continues to pump and clean blood, but the blood escapes. The patient is methodically drained and, unless someone intervenes, can die in minutes.

By some estimates, at least one American is killed this way every week.

A relatively simple solution is available in Europe: An alarm detects blood loss with a disposable sensor patch, then automatically shuts off the dialysis pump. Dialysis companies in the United States have not embraced this fail-safe technology, so it is largely unavailable to Americans. The alarm costs $649 and each patch about $2.25. Neither is covered by Medicare, which insures most dialysis patients.

“That’s the ugly side of dialysis,” said Debbie Brouwer-Maier, a 40-year dialysis nurse and member of the American Nephrology Nurses Association’s VND task force. She said the dialysis industry resists “any item that’s going to improve care if there is added cost.”

“The patch is the problem,” Brouwer-Maier said. “It’s a disposable you have to buy without being reimbursed for every single treatment the patient does.”

Currently, most American dialysis treatment occurs in a nationwide network of clinics where patients sit in rows of chairs for hours at a time about three times a week. Only about 2% of patients undergo hemodialysis at home, sometimes with the aid of family or a caregiver.

But hemodialysis is changing: The Trump and Biden administrations promoted home dialysis with increased Medicare payments. A new generation of portable machines offer better results, more independence, and a lower overall cost to the government and insurers. Home patients can be treated more often or for longer periods, putting less stress on their bodies, and may find it easier to travel or keep a day job.

Dialysis experts and patient advocates interviewed for this article agreed that many hemodialysis patients, if carefully selected and thoroughly trained, would benefit greatly from the momentum toward home care. Some also worry that no amount of training could erase the increased threat of needle dislodgment for those who dialyze at home while alone or asleep.

“It is the widowmaker heart attack of dialysis,” said Ankur Shah, a Brown University nephrologist. “If you have a VND at home, and you go one or two minutes before you recognize it, you are now trying to intervene while you are physically going into shock.”

Shah’s concerns are shared by others. In 2020, the nurse association task force found that patients who do hemodialysis at home or while asleep “may be at higher risk.” ECRI, a nonprofit focused on health care safety, named needle dislodgments a top health hazard for 2023 with a “particular concern” for patients at home. Both organizations said dialysis machines don’t reliably detect dislodgments, so blood pumps cannot be counted on to turn themselves off.

Ismael Cordero, an ECRI engineer who evaluates medical devices, said the absence of an automatic shut-off may also endanger patients in dialysis clinics, where a patient’s blanket could obscure a loose needle or staff members may not react in time.

Decades ago, Cordero witnessed a few dislodgments while working his way through college at a clinic in Pennsylvania. It was his job to mop up the blood.

“If that needle slips out, and no alarm goes off, and nobody notices, then within 10 minutes that patient would lose all of their blood,” he said.

Two companies make hemodialysis machines that the FDA has approved for home use.

Outset Medical, whose Tablo machines resemble a mini-fridge and were approved for home use in 2020, said in response to emailed questions that it has received no reports of VNDs among Tablo patients at home. The company said it believes VNDs may be more common or dangerous in a clinical setting than at home because staffers monitor multiple patients who are “frequently sleeping under blankets” and “completely disengaged from their treatment.”

“At home, a patient has been trained to manage themselves, including this rare event,” the company said in an email. “And despite the potential severity of the event, the treatment is simple and a procedure the patient performs every time they dialyze. Stop the blood pump.”

Fresenius, one of the world’s largest dialysis companies, which has sold NxStage hemodialysis machines for home use in the U.S. since 2005, declined to comment.

Despite the lethality of venous needle dislodgments, there is no accounting of how often they occur. The National Institutes of Health maintains voluminous data on kidney failure and dialysis patients but does not track VND events in clinics or at home. The Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services requires dialysis companies to log them internally but not to report them to the government or the public.

But research shows they do happen. A 2017 study by researchers in Portugal reported 88 venous needle dislodgments among about 733,000 dialysis sessions in one year. A 2012 survey of more than 1,100 dialysis nurses reported that 76% witnessed a dislodgment in the prior five years, and 8% said they had seen five or more. A 2008 study of dialysis clinics run by the Veterans Health Administration found 47 needle dislodgments or similar disconnects among 2.5 million sessions over a six-year span, including many that required hospitalization and some that were fatal.

Redsense Medical, a Swedish company that makes dialysis safety products, estimates that needle dislodgment kills three Americans and 21 people globally each week. But these estimates are extrapolated from a mid-2000s study from a single Pittsburgh hospital — one of the few efforts in the U.S. to count them.

Redsense’s signature product is a stand-alone alarm system, used by some clinics and home patients in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Australia. The system detects a needle dislodgment with a blood sensor patch, then sounds an alarm and flashes red lights to alert someone to turn off the pump.

But these alarms could be doing more. Since 2017, some Redsense alarms have also been able to send a signal that will automatically turn off a blood pump without human intervention. This fail-safe was requested by dialysis clinics in Europe, said Redsense CEO Pontus Nobréus, but it has never been submitted to the FDA for approval because no companies showed interest in using it in the United States.

Currently, no hemodialysis machine used in the U.S. is programmed to respond to the shut-off signal, Nobréus said.

“It hasn’t been used to its full potential, which is a pity,” Nobréus said. “We can send a signal to the machine, but the manufacturer has to have the software integrated to actually tell the machine to stop.”

Although Redsense alarms are not covered by Medicare, new legislation could change that. In May, Rep. Adrian Smith (R-Neb.) and Rep. Melanie Stansbury (D-N.M.) introduced the “Home Dialysis Risk Prevention Act,” which would extend Medicare coverage to VND alarms and related supplies for home patients only.

The bill was motivated in part by rural constituents who drive hours to dialysis clinics, Smith said, and he believes Medicare coverage lags far behind the latest dialysis technology.

“We want our public policy to be parallel with what technology can deliver,” Smith said, “and more than that, encourage innovation and more technology that will ultimately help patients.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.