On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner, walked into an elevator in downtown Tulsa, Okla. What happened next is unclear, but it sparked the Tulsa race massacre, one of the worst episodes of racial violence in U.S. history, with a death toll estimated in the hundreds.

A century later, researchers are still trying to find the bodies of the victims. A new excavation has brought renewed hope that these individuals could one day be found and identified.

By some accounts, Rowland may have tripped and bumped the arm of a 17-year-old white elevator operator named Sarah Page. Others said he stepped on her foot. Some recalled hearing her scream. Others wondered if the two had been sweet on each other and had a sort of lovers’ quarrel. Whatever happened, it was a dangerous time for a young Black man to be caught in a precarious situation with a young white woman.

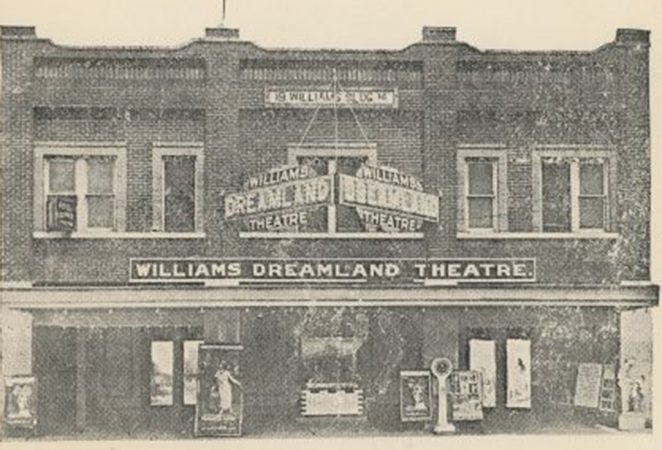

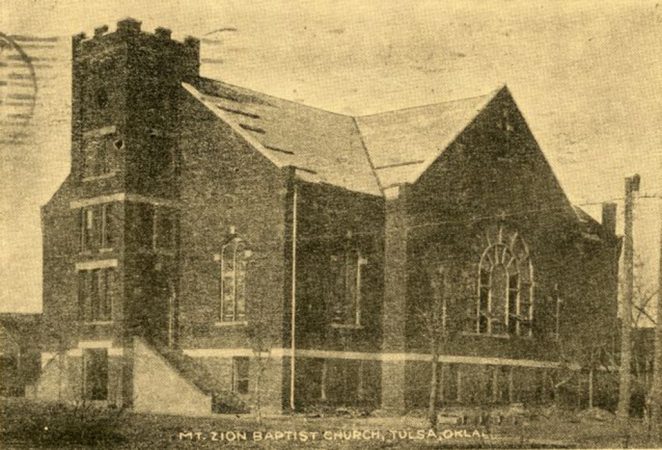

Tulsa’s population had skyrocketed to over 100,000 people. Most of the city’s African American residents, about 11,000, lived in a section called Greenwood. The neighborhood’s concentration of thriving entrepreneurs earned it the nickname “Black Wall Street” from Booker T. Washington in the early 1910s.

Greenwood became an oasis from racial prejudice and violence, says Alicia Odewale, a native Tulsan and archaeologist at the University of Tulsa. “You could buy land, create businesses and raise families.”

But amid its prosperity, the city was extremely segregated: Oklahoma passed a Jim Crow law immediately after it became a state in 1907, the Ku Klux Klan had a hand in local politics, and lynching was common. Tulsa reflected the racial tensions and violence across the United States after World War I. “There’s sort of a national pandemic of racial terror that’s happening, and Tulsa is unfortunately one city among a hundred,” Odewale says.

The day after the elevator incident, Rowland was arrested on a dubious charge of assault. Rumors circulated that he might be lynched. That night white mobs invaded Greenwood, setting fires, destroying property, looting shops and murdering Black residents. Instead of protecting the neighborhood, law enforcement handed out weapons and deputized white attackers. Machine gun fire echoed through Greenwood’s streets, and private planes dropped explosives and fired on those who fled.

For 24 hours Tulsa was a war zone.

By the evening of June 1, 35 square blocks smoldered, thousands of homes and businesses lay in ruin and a still unknown number of people were dead in the streets. A Red Cross report from 1921 suggests that about 800 people were wounded and 300 people died in the massacre, though the toll recorded by Oklahoma’s vital statistics bureau was just 36: 26 Black people and 10 white.

Tulsa Historical Society

A long history of racism, denial, deflection and cover up of the massacre has left deep wounds in the city’s Black communities. A century later, Tulsans still have questions: How many people died? Who were they? And where are they buried?

Answers to some of those questions now seem within reach thanks to an investigation that in October 2020 unearthed a mass grave believed to hold massacre victims. The finding brings some of those who lost their lives one step closer to being laid to rest properly. Future steps could involve DNA analysis to put names to the remains and possibly to reunite the dead with their families. But that prospect also raises concerns about privacy. And survivors and descendants have renewed their quest for reparations from the city and state.

Since 2018, when Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum launched the investigation, Greenwood descendants and community leaders have worked side by side with a multidisciplinary team of scientists and guided the process at each step. “Not only is the whole world watching, our children are watching,” says Kavin Ross, a local historian and descendant of massacre survivors. “Whatever we do, whatever we come up with, they’ll see how we are playing a role in history.”

In June, the team begins the careful process of exhuming remains from the mass grave and analyzing bones and artifacts for clues about the identity of the individuals and how they died.

A culture of silence

As the smoke cleared on June 1, 1921, Greenwood’s surviving Black residents were arrested and taken to internment sites. When they were released days later, many found themselves homeless and their neighborhood unrecognizable. No one was prosecuted for crimes committed during the massacre. Months later, Sarah Page told her lawyer she didn’t wish to prosecute. The district attorney dismissed the case against Dick Rowland. Both left town.

Over the next year, Tulsans filed $1.8 million in claims against the city; only one, a white pawn shop owner, received compensation. Some survivors left. Those who stayed rebuilt their homes and business themselves, in spite of the city’s attempts to block those efforts while blaming Greenwood residents for the violence.

For a long time, the people of Tulsa, Black and white, didn’t talk much about the massacre. The story was omitted from local historical accounts, and newspapers didn’t write about it until decades later. Black survivors kept quiet out of fear for their safety and because it was painful to recall.

Ross’ great-grandparents Mary and Isaac Evitt owned a popular Greenwood juke joint called the Zulu Lounge, where people would go to listen to music, dance and gamble. It was destroyed during the massacre, and the family’s experience was a touchy subject for his great-aunt Mildred. “She would get angry … refuse to even converse about it,” Ross says.

Tulsans have tried to find answers and search for the dead before. Rumors have persisted for a century that bodies were buried in mass graves around Tulsa, burned in the city’s incinerator and disposed of in the Arkansas River or down mine shafts outside of town. But no records of mass graves had ever been found. Death records from the period are sparse and often incomplete.

In 1997, Ross’ father, state Rep. Don Ross, introduced a joint resolution in the Oklahoma legislature that launched a commission to investigate the massacre. The commission set up a telephone tip line, and Clyde Eddy called in to report what he’d seen.

Growing up, Eddy often cut through Oaklawn Cemetery on his way to his aunt’s house. The then 10-year-old boy scout was with his cousin a few days after the massacre, when they spotted wooden crates the size of pianos strewn about at the edge of the cemetery. Nearby, men were digging a trench. Curious, the boys went over to investigate. They lifted the top of one crate and saw the dead bodies of three or four people stacked inside. They opened another crate and saw the same. Just as they were about to open a third crate, grave diggers chased them off. The boys lingered for a bit at the iron cemetery fence before walking on.

Returning to Oaklawn in his 80s, Eddy showed investigators where he’d seen the trench as a boy. A Scottie-shaped metal grave marker now stood nearby. A team of scientific consultants enlisted by the commission recommended excavating at Oaklawn.

But the city never broke ground.

At the time, the commission was divided on a slew of issues, including paying reparations to survivors devastated by the massacre and how to proceed respectfully with an excavation. “We got caught up in the politics of the day,” says Scott Ellsworth, a Tulsa-born historian at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who worked on both the 1997 investigation and the new one.

Intent on doing things differently the second time around, the city set up a series of committees to run the investigation launched in 2018: one for historical accounts, one for the physical investigation and one to provide public oversight — made up of community members who call the shots at each step of the process. Ross chairs the third group. “They’re the ones in the driver’s seat,” Odewale says.

Digging in

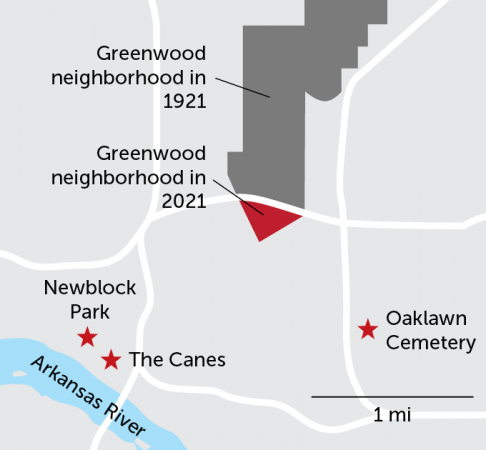

By the spring of 2019, historians began sifting through tips and interviews with more than 300 people. Investigators winnowed down the information from witnesses to the most promising prospects for finding mass graves: Oaklawn Cemetery just east of downtown, Newblock Park and the Canes area just west of downtown along the Arkansas River, and Rolling Oaks Memorial Gardens cemetery south of the city.

But digging didn’t begin right away.

“It’s not just about sticking a shovel in the ground,” says Kary Stackelbeck, the state archaeologist of Oklahoma at the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey in Norman. “You need to have a better way to narrow down your target.” One way to do that is using ground surveying technology that can reveal inconsistencies among natural layers of sediment.

For the surveys, the team used a gradiometer to measure subtle magnetic variations in soil; an electrical resistance meter, which sends electric currents into the ground to detect differences in soil moisture; and ground-penetrating radar, which measures how radar pulses bounce off underground objects, giving clues about their size and depth.

Using all three complementary techniques improves the chances of finding something, says Scott Hammerstedt, another Oklahoma Survey archaeologist. For example, big metal objects can interfere with the gradiometer and power lines mess with the electrical resistance meter scans.

Archaeologists walk or push the machines over the ground like a zigzagging lawnmower. Then they look for anomalies — like waves in the gray radar scans or dark spots on gradiometer scans. “All of these things really pick up contrast between the undisturbed surrounding soil and the archaeological features that we’re looking for,” Hammerstedt says. Then comes the digging, to learn whether that area of contrast is in fact a grave.

At Newblock Park, flagged as a site where people had seen piles of bodies in 1921, ground scans didn’t turn up anything significant. Across the train tracks and downriver from Newblock, the Canes was another area of interest.

A retired Tulsa police officer recalled seeing a photograph of bodies piled in a trench, which he found in the 1970s among boxes of images confiscated from photo studios after the massacre. He recognized the area as the Canes. That concurred with eyewitness accounts of bodies stacked on a river sandbar and buried somewhere in the vicinity. Today, that area hosts an encampment of people who are homeless. Ground-penetrating radar flagged two areas there, each about 2 by 3 meters.

The owners of Rolling Oaks did not grant access to investigators until recently, so it was not in the initial survey.

Finally, the team surveyed Oaklawn Cemetery — where Eddy had seen those piano-sized crates a century ago. Jackson Funeral Home in Greenwood, which served the Black community at the time, had been burned to the ground. But owner Samuel Jackson was released from internment and taken to one of the city’s white funeral homes to care for Black massacre victims whose bodies were being held there. The 1997 investigation had revealed death certificates of those individuals: Eighteen Black men and an infant were buried in unmarked graves somewhere at Oaklawn. In 1921, the Tulsa Daily World had also reported burials of Black victims at the cemetery. There lie Eddie Lockard and Reuben Everett, the only massacre victims whose graves were marked — likely because they were buried after their families were released from internment sites.

Oaklawn had three survey sites that were possible graves: an area flagged by cemetery caretakers as a place where victims were buried, a spot that matched Eddy’s description in the white section of the potter’s field — a burial ground for people who were poor — and an area in the Black potter’s field near the two marked graves.

Scanning had shown a big, 8-by-10-meter area beneath the surface with distinct walls in the section pointed out by the cemetery caretakers. “It really had these hallmarks that suggested it might be a mass grave,” Stackelbeck says.

Breaking ground

In July 2020, after a slight delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the team began test excavations at Oaklawn. A backhoe removed soil layer by layer, inches at a time, as archaeologists watched carefully for subtle changes in soil color and texture, and for any hint of a burial.

City of Tulsa

Gravedigging involves removing soil to the depth of several feet, then refilling the grave shaft with that soil. “Long before humans were walking around Tulsa, weathering of sedimentary rock exposed to the elements created layers of soil, and when humans come along and dig things up, those layers mix, destroying the original soil characteristics,” says Deb Green, a geoarchaeologist with the Oklahoma Survey. At Oaklawn, deep soil is yellowish brown, with a crumbly texture like silt, When mixed with gray topsoil, it gets darker and starts to feel more like compact clay over time. These qualities appear both in regular graves and mass graves.

During an archaeological excavation, the goal is to stop the backhoe before it hits a burial, so the archaeologists look for other clues that remains might be present. The soil above a coffin with a decaying body is darker and higher in organic carbon than the surrounding area, and sometimes contains pockets of air. Nails and hinges can leach iron that turns dirt red, and decaying wood can leave a coffin outline in the sediment.

As the backhoe dug deeper, wood fragments, glass, pottery shards and artifacts came to the surface. Remnants of overlapping historic roads and a pond emerged from the soil.

The team found a bone. But it turned out to be from a farm animal. Wearily the researchers concluded that the anomaly they’d seen in the scans was likely an old dumping ground for temporary burial markers, offerings and other debris.

“It was definitely deflating because we felt a deep sense of responsibility and there had been so much buildup,” Stackelbeck says. “But this is how science works. You put together your best game plan, but sometimes the data don’t play out that way.”

The Original 18

The team then tried to locate the burials that Clyde Eddy saw, with no luck. Finally, the investigators turned their attention to the area of the Black potter’s field and the two marked graves, a site they dubbed the Original 18, for those 18 Black men mentioned in the funeral home records.

Based on newspaper accounts and funeral home records, the team thought the Original 18 had been buried in individual graves, so the group focused on a soil anomaly that looked like a single grave. The backhoe returned and began to scrape away at the soil layers.

On the second day, it hit wood and bone. This time the bone was human. But it still caught the group off guard.

“The first burial didn’t match what we expected to find, because [it] was a woman, and her casket wasn’t plain,” says Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville who is on the excavation team, and whose aunt lost her house in the massacre. The original 18 victims from the death certificates were all male and buried in plain caskets. Bearing a simple metal plate that read “At Rest,” the unidentified woman’s coffin resembled a standard pauper burial of the time. “If your family couldn’t afford a more formal burial, the city paid Oaklawn $5.04 to bury you in a lined casket with eight screws and a plate on top,” Stubblefield says. Whoever she was, this woman was probably not a massacre victim, Stubblefield suspects.

But soil cores revealed that the disturbed area was bigger than a single grave shaft.

As the archaeologists followed the soil patterns and dug a trench, the outlines of fragile coffins began to emerge, along with human bone fragments, hinges and nails. The coffins are close together in two rows, possibly stacked. Samples of two coffin fragments revealed pine wood construction.

At the end of the burial pit were steps dug into the earth. “They were haunting,” Stackelbeck says. “You don’t need stairs to dig a grave for one person or even two or three people.”

The crew had unearthed a mass grave.

“Here was proof that there was truth buried underneath Tulsa,” says Ross, the local historian. “I felt justified.”

In that trench, the investigators found 12 coffins in all, but hinges and decaying wood suggest there are at least three more. “Based on the sheer number of individuals, this certainly meets the definition of a mass grave,” says Soren Blau, a forensic anthropologist at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine in Melbourne, Australia. “This is not how we respectfully bury our dead,” Blau says.

While historical and preservation context varies, mass graves usually consist of a large, unmarked burial pit, sometimes with steps if dug by shovel or ramping to facilitate digging by machine.

City of Tulsa

On June 1, the excavation and exhumation of the remains will begin. The unidentified woman’s burial gives researchers an idea of what they might find. Large bone fragments and teeth appear to be well-preserved, but smaller bones like vertebrae or thin rib bones likely didn’t survive as well.

Using trauma patterns and gender clues in the bones, Stubblefield, who also worked on the 1997 investigation, will assess whether the individuals in the mass grave are massacre victims. She’ll be looking for bullet wounds and shotgun trauma. If there are actual bullets, her team might be able to determine their caliber. Based on their location in the cemetery, the graves should be from the 1920s, when the only other mass casualty event would have been the 1918 flu pandemic. But there are no records of flu victims being buried in mass graves in Tulsa.

The researchers will also search the coffins for personal effects and textiles that could help reveal facets of the identity and social standing of the dead.

City of Tulsa

DNA insights and limits

Putting names to the deceased will be hard, and could take years. Because the death certificates of the Original 18 had scant details and listed most individuals as having died from gunshot wounds, no document has enough unique information to aid identification efforts. DNA would give the team its best chance at an ID, but after a century, any DNA extracted from teeth or bone may not be intact. Specialized techniques used to study ancient DNA might be needed (SN: 2/17/21).

If DNA is preserved, a clear set of rules will be needed to guide who has access to those sequences and what analyses can be done. “Academia loves genetic sequences,” Stubblefield says. “We don’t want to get the profiles and see 10 years of publications on Greenwood individuals without acknowledgement or communication with the community.” Cautionary tales come to mind, like the use of cells from Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman diagnosed with cancer in the 1950s, who was not told her cells might be used for research, yet those cells led others to profit, making important vaccines against polio and HPV (SN: 3/27/10). “There’s a frequent issue with the misuse of Black bodies in science,” Stubblefield says.

Finding relatives would require DNA from descendants. Consumer DNA testing companies, which have large databases, would give researchers a better chance of finding distant cousins, but using those comes with concerns about consent and privacy (SN: 6/5/18). Depending on company policies, that data can end up in public databases or accessed by law enforcement (SN: 11/12/19).

“You don’t want to ask people to participate in the reconciliation or resolution of historical trauma in a way that might put them at risk in new ways,” says Alondra Nelson, a sociologist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J. In an ideal world, Greenwood-related DNA would be separated from a company’s larger database or handled through private labs, she says.

The project’s public oversight committee recently brought in a geneticist to talk about how DNA identification might inform the way forward. “It needs to be the community’s decision,” Stubblefield says. “We just want to make sure that privacy interests are addressed.”

The three remaining known survivors of the massacre, all 100 years or older, are suing the city for reparations. DNA results might play a role in future reparations efforts. “Genetics can provide people with inferences and context that allow them to make claims about the past and make claims about what’s owed to them in the present and future,” Nelson says.

Greenwood rising

Reckoning with what happened in 1921 means looking at the victims as people, not just death statistics, Odewale says. “We need to talk about how they lived, not just how they died.”

Odewale leads an effort to understand the aftermath of the massacre. The goal of this work, which is happening at the same time as the mass graves project, is to search for signs of structural survival in Greenwood — building foundations, walls, anything that might have withstood the burning — and map how the neighborhood has changed since 1921.

Courtesy of Alicia Odewale

“We see cycles of both destruction and construction in Greenwood,” she says. “It’s not just a site of Black trauma but also one of resilience.” Geophysical surveys have already turned up promising excavation prospects, and Odewale and her colleagues will break ground this summer.

The mass graves project is about finding lost ancestors, Odewale says, while her project in Greenwood is about understanding the roots of the community. “We need both to move forward,” she says.

Much more work lies ahead to excavate and identify remains and uncover modern complexities associated with Tulsa’s buried past. The researchers hope to excavate more sites and revisit old ones. Tips are still coming in, this time through the city’s website.

“We have been waiting a hundred years for what we’ve found so far,” Ross says. “We hope that we don’t have to wait another hundred years trying to find the truth.”

The latest findings show that with clever science, a single fingerprint left at a crime scene could be used to determine whether someone has touched or ingested class A drugs.

The latest findings show that with clever science, a single fingerprint left at a crime scene could be used to determine whether someone has touched or ingested class A drugs. Fields of opium poppies once bloomed where the Zurich Opera House underground garage now stands.

Fields of opium poppies once bloomed where the Zurich Opera House underground garage now stands.