Whatever happened to the anti-alcohol movement?

By Olga Khazan

Posted on January 14, 2020 on The Atlantic

Occasionally, Elizabeth Bruenig unleashes a tweet for which she knows she’s sure to get dragged: She admits that she doesn’t drink.

Bruenig, a columnist at The New York Times with a sizable social-media following, told me that it usually begins with her tweeting something mildly inflammatory and totally unrelated to alcohol – e.g., The Star Wars prequels are actually good. Someone will accuse her of being drunk. She, in turn, will clarify that she doesn’t drink, and that she’s never been drunk. Inevitably, people will criticize her. You’re really missing out, they might say. Why would you deny yourself?

As Bruenig sees it, however, there’s more to be gained than lost in abstaining. In fact, she supports stronger restrictions on alcohol sales. Alcohol’s effects on crime and violence, in her view, are cause to reconsider some cities’ and states’ permissive attitudes toward things such as open-container laws and where alcohol can be sold.

Breunig’s outlook harks back to a time when there was a robust public discussion about the role of alcohol in society. Today, warnings about the devil drink will win you few friends. Sure, it’s fine if you want to join Alcoholics Anonymous or cut back on drinking to help yourself, and people are happy to tell you not to drink and drive. But Americans tend to reject general anti-alcohol advocacy with a vociferousness typically reserved for IRS auditors and after-period double-spacers. Pushing for, say, higher alcohol taxes gets you treated like an uptight school marm. Or worse, a neo-prohibitionist.

Unlike in previous generations, hardly any formal organizations are pushing to reduce the amount that Americans drink. Some groups oppose marijuana (by many measures a much safer drug than alcohol), guns, porn, junk food, and virtually every other vice. Still, the main U.S. organizations I could track down that are by any definition anti-alcohol are Mothers Against Drunk Driving—which mainly focuses on just that—and a small nonprofit in California called Alcohol Justice. In a country where there is an interest group for everything, one of the biggest public-health threats is largely allowed a free pass. And there are deep historical and commercial reasons why.

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.”

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.”

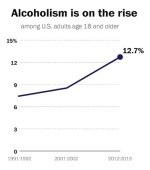

Alcohol’s byproducts wreak havoc on the cells, raising the risk of liver disease, heart failure, dementia, seven types of cancer, and fetal alcohol syndrome. Just this month, researchers reported that the number of alcohol-related deaths in the United States more than doubled in two decades, going up to 73,000 in 2017. As the journalist Stephanie Mencimer wrote in a 2018 Mother Jones article, alcohol-related breast cancer kills more than twice as many American women as drunk drivers do. Many people drink to relax, but it turns out that booze isn’t even very good at that. It seems to have a boomerang effect on anxiety, soothing it at first but bringing it roaring back later.

Despite these grim statistics, Americans embrace and encourage drinking far more than they do similar vices. Alcohol is the one drug almost universally accepted at social gatherings that routinely kills people. Cigarette smoking remains responsible for the deaths of nearly 500,000 Americans each year, but the number of smokers has been dropping for decades. And few companies could legally stock a work happy hour with joints and bongs, which have never caused a lethal overdose, but many bosses ply their workers with alcohol, which can be poisonous in large quantities.

America arrived at this point in part because the end of Prohibition took the wind out of the sails of temperance groups. When the nation’s 13-year ban on alcohol ended in 1933, alcohol control was left up to states and municipalities to regulate. (This is why there are now dry counties and states where you can’t buy alcohol in grocery stores.) At the national level, anti-alcohol efforts were “tainted with an aura of failure,” writes the wine historian Rod Phillips in Alcohol: A History. Membership in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the original prohibitionist group, declined from more than 2 million in 1920 to fewer than half a million in 1940. Some Christian groups continued to push for restrictions on things such as liquor advertising throughout the ’40s and ’50s. But eventually alcohol dropped off as a major national political issue and was eclipsed by President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs such as marijuana and heroin.

This dearth of anti-alcohol advocacy was met with a gradual shift in the way Americans began to view alcoholism—and with commercial interests that were ready to step into the breach. When Alcoholics Anonymous was founded in 1935, it portrayed alcoholism as a disease rather than a moral scourge on society, says Aaron Cowan, a history professor at Slippery Rock University, in Pennsylvania. (In time, the medical community would come to agree with the idea of alcohol abuse as a medical disorder.) By emphasizing individual rather than social reform, the organization helped cement the idea that the problem was not alcohol writ large, but the small percentage of people who could not drink alcohol without becoming addicted. The thinking became, If you have a problem with alcohol, why don’t you get help? Why ruin everyone else’s fun?

Of course, many people have a normal relationship with alcohol, which has been a fixture of social life since the time of the Sumerians and ancient Egyptians. But today, what actually constitutes a “normal” relationship with alcohol can be difficult to determine, because Americans’ views have been influenced by decades of careful marketing and lobbying efforts. Specifically, beer, wine, and spirit manufacturers have repeatedly tried to normalize and exculpate drinking. “The alcohol industry has done a great job of marketing the product, of funding university research looking at the benefits of alcohol, and using its influence to frame the issue as one of ‘The problem is hazardous drinking, and as long as you drink safely, you’re fine,’” says Michael Siegel, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University.

During World War II, the brewing industry recast beer as a “moderate beverage” that was good for soldiers’ morale. One United States Brewers’ Foundation ad from 1944 depicts a soldier writing home to his sweetheart and dreaming of enjoying a glass of beer in his backyard hammock. “By the end of the war, the wine industry, the distilled-spirits industry, and the brewing industry had really defined themselves as part of the American fabric of life,” says Lisa Jacobson, a history professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

In later decades, beer companies created the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation, now called the Foundation for Alcohol Research, which proceeded to give research grants to scientists, some of whom found health benefits to drinking. More recently, the National Institutes of Health shut down a study on the effects of alcohol after The New York Times reported that it was funded by alcohol companies. (George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, told the Times that the foundation through which the funds were channeled is a type of “firewall” that prevents interference from donors.)

Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.

Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.

(In an email, the NBWA spokeswoman Lauren Kane said, “The alcohol industry has varying views when it comes to regulation, but NBWA will continue to advocate for laws and policies that support public health and safety through thoughtful, common-sense alcohol regulation led by the states.”)

A few temperance organizations are still out there, says Mark Schrad, a political-science professor at Villanova University, but they’re more active in Europe. Alcohol Justice, the California nonprofit, supports tighter limits on alcohol sales and advertising. But Bruce Lee Livingston, the group’s executive director, says that because many nonprofits are dependent on state, federal, and county grants, it’s difficult for the group to lobby policy makers. And nonprofits’ forces are dwarfed by the firepower of the alcohol industry. “Alcohol has, to a large extent, been abandoned by foundations and certainly is not funded by direct corporate donations, so alcohol prevention as a field of advocacy is very limited,” Livingston says.

The way Bruenig sees it, pop culture tends to depict society as split between “good guys” who just want to have fun and “bad guys” who want to destroy all the fun. If you’re someone who calls alcohol into question, she said, “you get kind of recruited against your will into this anti-fun agenda.”

Regardless of how much Americans love to drink, the country could be safer and healthier if we treated booze more like we treat cigarettes. The lack of serious discussion about raising alcohol prices or limiting its sale speaks to all the ground Americans have ceded to the “good guys” who have fun. And judging by the health statistics, we’re amusing ourselves to death.

The post America’s Favorite Poison first appeared on AA Agnostica.

![Do Tell! [Front Cover]](https://nrdblogs.nationalrehabdirectory.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Do-Tell-Full-Blue-Front-Cover-200-FRAMED.jpg) This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.