DENVER — Seven years ago, Erica Green learned through a Facebook post that her brother had been shot.

She rushed to check on him at a hospital run by Denver Health, the city’s safety-net system, but she was unable to get information from emergency room workers, who complained that she was creating a disturbance.

“I was distraught and outside, crying, and Jerry came out of the front doors,” she said.

Jerry Morgan is a familiar face from Green’s Denver neighborhood. He had rushed to the hospital after his pager alerted him to the shooting. As a violence prevention professional with the At-Risk Intervention and Mentoring program, or AIM, Morgan supports gun-violence patients and their families at the hospital — as he did the day Green’s brother was shot.

“It made the situation of that traumatic experience so much better. After that, I was, like, I want to do this work,” Green said.

Today, Green works with Morgan as the program manager for AIM, a hospital-linked violence intervention program launched in 2010 as a partnership between Denver Health and the nonprofit Denver Youth Program. It since has expanded to include Children’s Hospital Colorado and the University of Colorado Hospital.

AIM is one of dozens of hospital-linked violence intervention programs around the country. The programs aim to uncover the social and economic factors that contributed to someone ending up in the ER with a bullet wound: inadequate housing, job loss, or feeling unsafe in one’s neighborhood, for example.

Such programs that take a public health approach to stopping gun violence have had success — one in San Francisco reported a fourfold reduction in violent injury recidivism rates over six years. But President Donald Trump’s executive orders calling for the review of the Biden administration’s gun policies and trillions of dollars in federal grants and loans have created uncertainty around the programs’ long-term federal funding. Some organizers believe their programs will be just fine, but others are looking to shore up alternative funding sources.

“We’ve been worried about, if a domino does fall, how is it going to impact us? There’s a lot of unknowns,” said John Torres, associate director for Youth Alive, an Oakland-based nonprofit.

Federal data shows that gun violence became a leading cause of death among children and young adults at the start of this decade and was tied to more than 48,000 deaths among people of all ages in 2022. New York-based pediatric trauma surgeon Chethan Sathya, a National Institutes of Health-funded firearms injury prevention researcher, believes those statistics show that gun violence can’t be ignored as a health care issue. “It’s killing so many people,” Sathya said.

Research shows that a violent injury puts someone at heightened risk for future ones, and the risk of death goes up significantly by the third violent injury, according to a 2006 study published in The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care.

Benjamin Li, an emergency medicine physician at Denver Health and the health system’s AIM medical director, said the ER is an ideal setting to intervene in gun violence by working to reverse-engineer what led to a patient’s injuries.

“If you are just seeing the person, patching them up, and then sending them right back into the exact same circumstances, we know it’s going to lead to them being hurt again,” Li said. “It’s critical we address the social determinants of health and then try to change the equation.”

That might mean providing alternative solutions to gunshot victims who might otherwise seek retaliation, said Paris Davis, the intervention programs director for Youth Alive.

“If that’s helping them relocate out of the area, if that’s allowing them to gain housing, if that’s shifting that energy into education or job or, you know, family therapy, whatever the needs are for that particular case and individual, that is what we provide,” Davis said.

AIM outreach workers meet gunshot wound victims at their hospital bedsides to have what Morgan, AIM’s lead outreach worker, calls a tough, nonjudgmental conversation on how the patients ended up there.

AIM uses that information to help patients access the resources they need to navigate their biggest challenges after they’re discharged, Morgan said. Those challenges can include returning to school or work, or finding housing. AIM outreach workers might also attend court proceedings and assist with transportation to health care appointments.

“We try to help in whatever capacity we can, but it’s interdependent on whatever the client needs,” Morgan said.

Since 2010, AIM has grown from three full-time outreach workers to nine, and this year opened the REACH Clinic in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. The community-based clinic provides wound-care kits; physical therapy; and behavioral, mental and occupational health care. In the coming months, it plans to add bullet removal to its services. It’s part of a growing movement of community-based clinics focused on violent injuries, including the Bullet Related Injury Clinic in St. Louis.

Ginny McCarthy, an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Colorado, described REACH as an extension of the hospital-based work, providing holistic treatment in a single location and building trust between health care providers and communities of color that have historically experienced racial biases in medical care.

Colorado, who works closely with the Denver Youth Program, opens up a take-home wound-care kit, which is offered at the REACH Clinic. The clinic’s services are offered to the community at no charge and, in the coming months, the hope is to add bullet removal care.(Stephanie Wolf for KFF Health News)

Caught in the Crossfire, created in 1994 and run by Youth Alive in Oakland, is cited as the nation’s first hospital-linked violence intervention program and has since inspired others. The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention, a national network initiated by Youth ALIVE to advance public health solutions to gun violence, counted 74 hospital-linked violence intervention programs among its membership as of January.

The alliance’s executive director, Fatimah Loren Dreier, compared medicine’s role in addressing gun violence to that of preventing an infectious disease, like cholera. “That disease spreads if you don’t have good sanitation in places where people aggregate,” she said.

Dreier, who also serves as executive director of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Gun Violence Research and Education, said medicine identifies and tracks patterns that lead to the spread of a disease or, in this case, the spread of violence.

“That is what health care can do really well to shift society. When we deploy this, we get better outcomes for everybody,” Dreier said.

The alliance, of which AIM is a member, offers technical assistance and training for hospital-linked violence intervention programs and successfully petitioned to make their services eligible for traditional insurance reimbursement.

In 2021, President Joe Biden issued an executive action that opened the door for states to use Medicaid for violence prevention. Several states, including California, New York, and Colorado, have passed legislation establishing a Medicaid benefit for hospital-linked violence intervention programs.

Last summer, then-U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared gun violence a public health crisis, and the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act earmarked $1.4 billion in funding for a wide array of violence-prevention programs through next year.

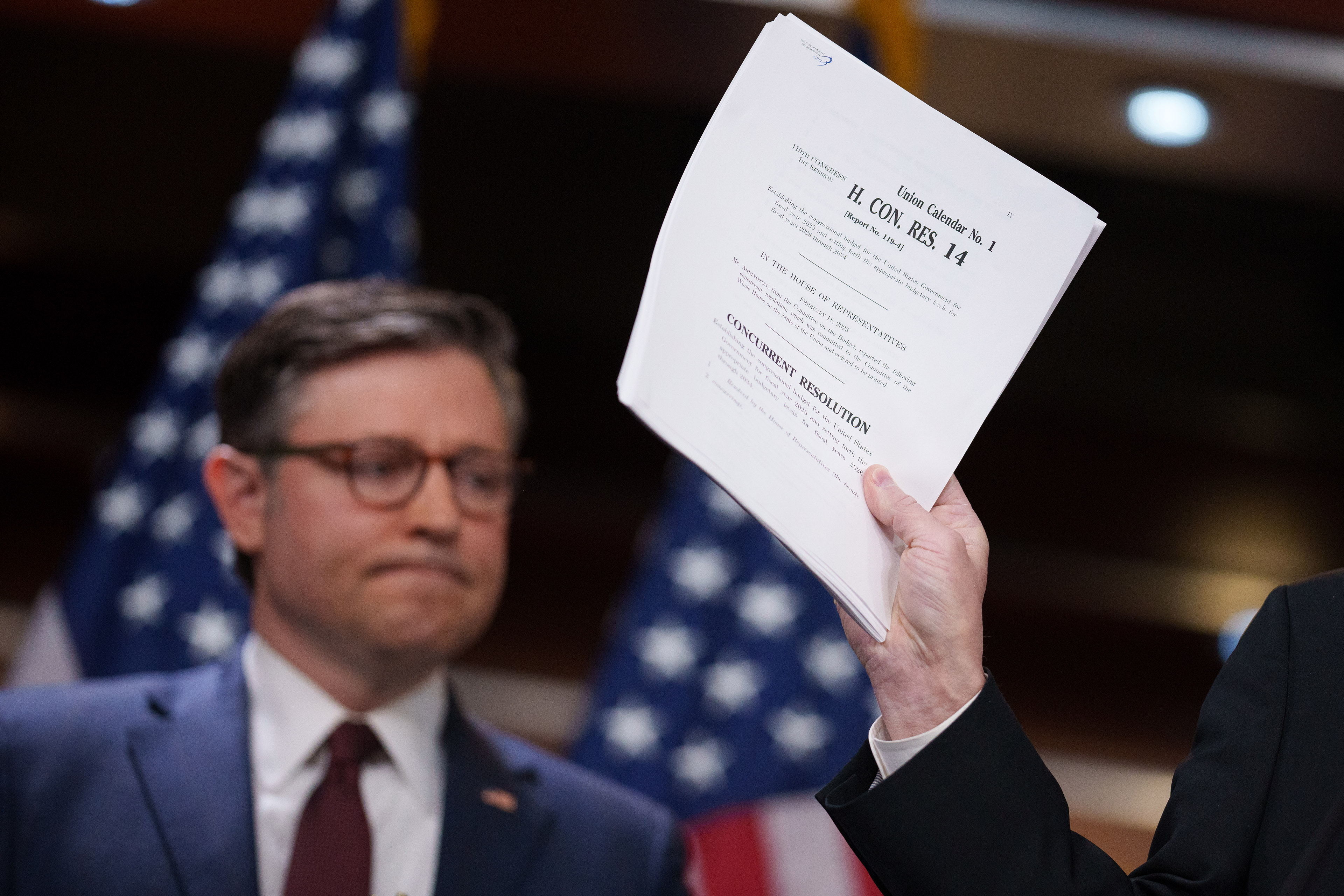

But in early February, Trump issued an executive order instructing the U.S. attorney general to conduct a 30-day review of a number of Biden’s policies on gun violence. The White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention now appears to be defunct, and recent moves to freeze federal grants created uncertainty among the gun-violence prevention programs that receive federal funding.

AIM receives 30% of its funding from its operating agreement with Denver’s Office of Community Violence Solutions, according to Li. The rest is from grants, including Victims of Crime Act funding, through the Department of Justice. As of mid-February, Trump’s executive orders had not affected AIM’s current funding.

Some who work with the hospital-linked violence prevention programs in Colorado are hoping a new voter-approved firearms and ammunition excise tax in the state, expected to generate about $39 million annually and support victim services, could be a new source of funding. But the tax’s revenues aren’t expected to fully flow until 2026, and it’s not clear how that money will be allocated.

Trauma surgeon and public health researcher Catherine Velopulos, who is the AIM medical director at the University of Colorado hospital in Aurora, said any interruption in federal funding, even for a few months, would be “very difficult for us.” But Velopulos said she was reassured by the bipartisan support for the kind of work AIM does.

“People want to oversimplify the problem and just say, ‘If we get rid of guns, it’s all going to stop,’ or ‘It doesn’t matter what we do, because they’re going to get guns, anyway,’” she said. “What we really have to address is why people feel so scared that they have to arm themselves.”