KINGSPORT, Tenn. — Jerry Qualls had a heart attack in 2022 and was rushed by ambulance to Holston Valley Medical Center, where he was hospitalized for a week and kept alive by a ventilator and blood pump, according to his medical records.

His wife, Katherine Qualls, said his doctors offered little hope. In an interview and a written complaint to the Tennessee government, she said doctors at Holston Valley told her that her husband would not qualify for a heart transplant and shouldn’t be expected to recover.

Defiant, she insisted he be transferred hours away to a hospital in Nashville. Within days of leaving Holston Valley, Jerry Qualls was awake and sitting upright, his wife said, and he ultimately received a lifesaving heart transplant.

“How many families don’t know how to get a transfer and their loved one dies?” Katherine Qualls wrote in her complaint to the state. “My husband would have been dead within a few days if I didn’t get him out when I did.”

Holston Valley Medical Center is a flagship of Ballad Health, a 20-hospital system in northeastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia that is the only option for hospital care in a large swath of Appalachia. Ballad formed six years ago when lawmakers in both states, in an effort to prevent hospital closures, waived federal antitrust laws so two rival health systems could merge. The merger created the largest state-sanctioned hospital monopoly in the nation.

Since then, Ballad has largely kept those hospitals open. But the monopoly has also fallen short of about three-fourths of the quality-of-care goals set by the states over the last three fiscal years, including failing to meet state benchmarks on infections, mortality, emergency room speed, and patient satisfaction, according to annual reports from the Tennessee Department of Health and Ballad itself.

Some local residents have become wary, afraid, or unwilling to seek care at Ballad hospitals and must drive over an hour to reach other options, according to written complaints to the Tennessee government and state lawmakers, public hearing testimony, and KFF Health News interviews conducted over the past year with patients, family members, local leaders, and some officials who once publicly supported the monopoly, including a former government consultant and one state lawmaker. Many of those who submitted complaints or were interviewed allege that paper-thin staffing at Ballad hospitals and ERs is the root cause of the monopoly’s quality-of-care woes.

In a two-hour interview vigorously defending the company, Ballad Health CEO Alan Levine said the hospitals are rapidly recovering from a quality-of-care slump caused by covid-19 and a subsequent rise in nursing turnover and staff shortages. These issues affected hospitals nationwide, Levine said, and were not related to the Ballad merger or the monopoly it created.

Levine declined to discuss specific complaints from patients. But he said that each of the complaints referenced in this article took issue with medical decisions made by doctors in Ballad hospitals — not “any policy or practice at Ballad.”

“I can understand if the patients, if the wife, was upset about the medical decisions they made if it turned out to be wrong,” Levine said. “But that has nothing to do with the merger, OK? That’s a completely different issue, and it happens in hospitals all over the country.”

In the interview with KFF Health News and in the days that followed, Levine flexed considerable connections to officials in the Tennessee government. As Levine spoke in a boardroom at Ballad’s hilltop headquarters, he was flanked by three local mayors who voiced support for the hospitals and said complaints came from a vocal minority of their constituents. Days later, Levine got two Tennessee state agency directors and a former state health commissioner to provide emails or text messages supporting statements he made during the interview.

Logan Grant, executive director of the Tennessee Health Facilities Commission, which processes complaints against hospitals for the state, said in a statement prompted by Levine that Ballad hospitals are “not an outlier in terms of substantiated survey findings.”

Joe Grandy, the mayor of Tennessee’s Washington County, where Ballad is headquartered, said most residents consider the quality of care in the area “about as good as it gets.”

Brenda Getaz certainly doesn’t.

Getaz, 76, who spent three decades as a hospital official specializing in quality standards before retiring to Washington County, said she plans to move to Atlanta if state governments do not take action to fix Ballad in the coming year. Getaz said local medical professionals she trusts have urged her to move away so she does not have to rely on Ballad for care.

“I’m frightened to be taken to a Ballad facility,” she said.

Glimpses of Government Concern

The Tennessee Department of Health, which has the most direct oversight over Ballad Health, over the past year has declined multiple interview requests to discuss the hospital monopoly. Department emails reviewed by KFF Health News, some of which were obtained through public record requests, offer glimpses of concern inside the agency.

Emails show the health department has attempted to hold Ballad more accountable for its quality of care in closed-door negotiations and is investigating Holston Valley’s treatment of a recent heart patient after receiving detailed complaints from his family. In a 2023 email, Tennessee Health Commissioner Ralph Alvarado reacted to a news story about low job satisfaction among Ballad nurses by writing: “Ouch. … What are they doing to address this?”

In another email from the same year, Alvarado praised an informal report submitted at a public hearing that concluded Ballad’s monopoly had caused more harm than good. The report was written by Wally Hankwitz, a retired health care executive who once led a physician management company in Kingsport. The report levied pages of criticism against Ballad’s “sub-par” performance and called for the monopoly to end.

“THIS communication from the COPA hearing is particularly good,” the health commissioner wrote to some of his staff. “Totally based on data. I would almost like to hear Ballad’s response to this.”

When asked to respond to the Hankwitz report, Levine said it was “full of errors” and that “no credible institution would pay attention to it.”

Despite concerns, Tennessee and Virginia have each year determined that the benefits of the Ballad monopoly outweigh any negative impacts, issuing stamps of approval that allow the monopoly to continue. This has occurred, at least in part, because both states grade Ballad against scoring rubrics that do not prioritize quality of care.

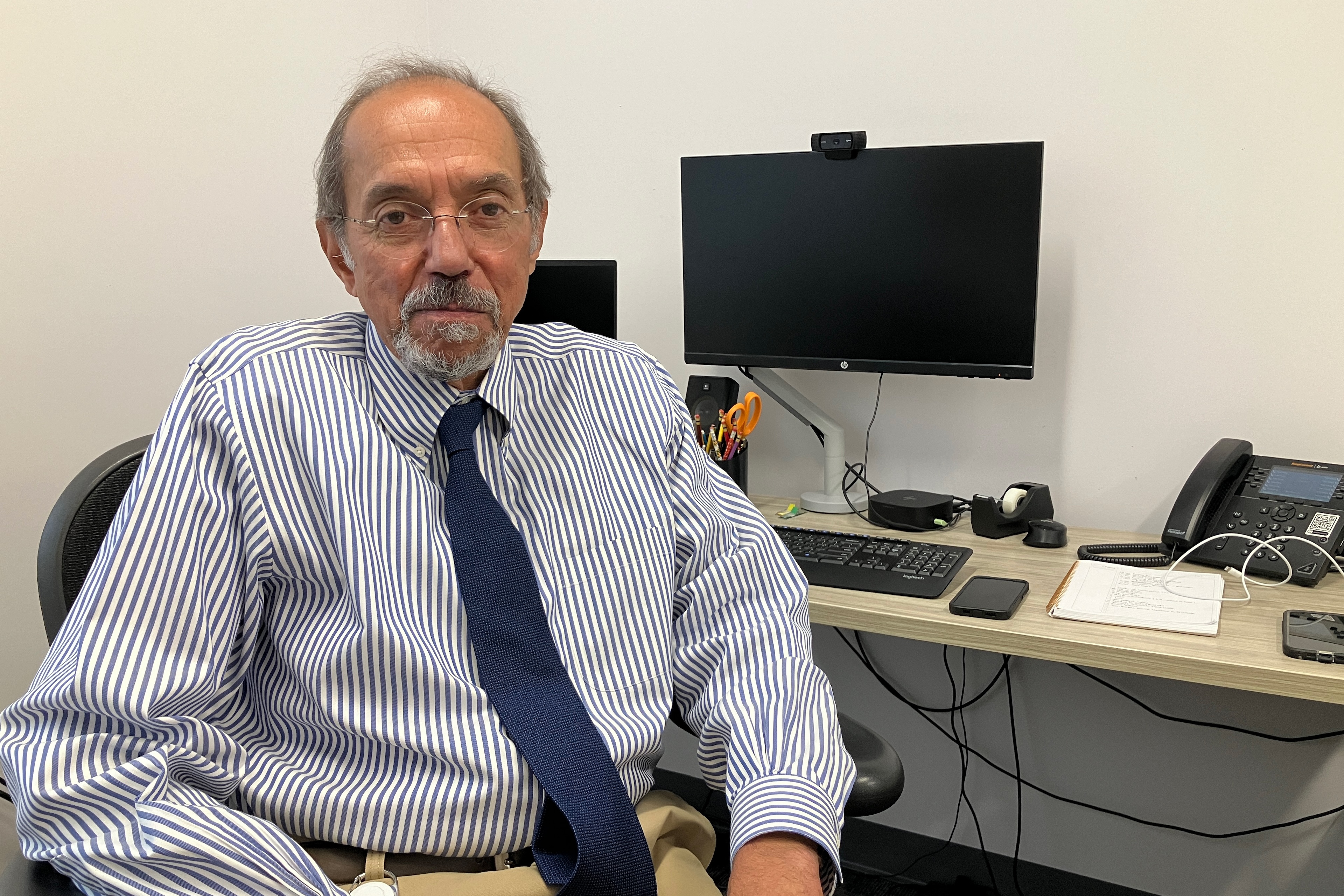

Larry Fitzgerald, a retired Tennessee consultant who monitored the monopoly for the state for more than five years and always gave Ballad high marks, said in an interview that his hands were tied by the state’s lenient grading system, which allowed Ballad to succeed on paper even when it failed to meet the state’s quality-of-care goals.

Fitzgerald said he is unconvinced that the state-sanctioned monopoly had prevented any hospital closures and said the merger had “probably not” benefited local residents overall.

When asked where he would get medical attention if he lived in northeastern Tennessee or southwestern Virginia, Fitzgerald immediately responded, “I’m not going to a Ballad hospital.”

In his interview, Levine alleged Fitzgerald had “basically defrauded the state” by not raising these criticisms of Ballad in his public reports on the monopoly and said it was “irresponsible” and “obscene” to express his concerns about quality of care after retiring.

‘Horror Stories’ From Ballad Patients

Tennessee House member Bud Hulsey, a Republican from Kingsport, wrote in a 2023 letter to the state health department that he “was an avid supporter of the merger” that created Ballad but since then had become “concerned” and “saddened” by the state of the local hospitals.

In a recent interview, Hulsey said that while his family has received excellent care from Ballad, his constituents have told him “horror stories” for years.

“I had people call me from the waiting room after they’ve sat there for 12 or 14 hours,” Hulsey said. “The scales have far more complaints on them than accolades.”

Others have soured on the monopoly, too. Joe Macione, who for years was on the board of Wellmont Health System, one of the rival companies that became Ballad, once publicly advocated for the merger.

In an interview, Macione said state leaders should have admitted years ago that the monopoly was a mistake.

“It has not worked,” said Macione, 87. “All my family knows that, if I have the time, I want to go to a highly graded hospital, either in Asheville or Knoxville.”

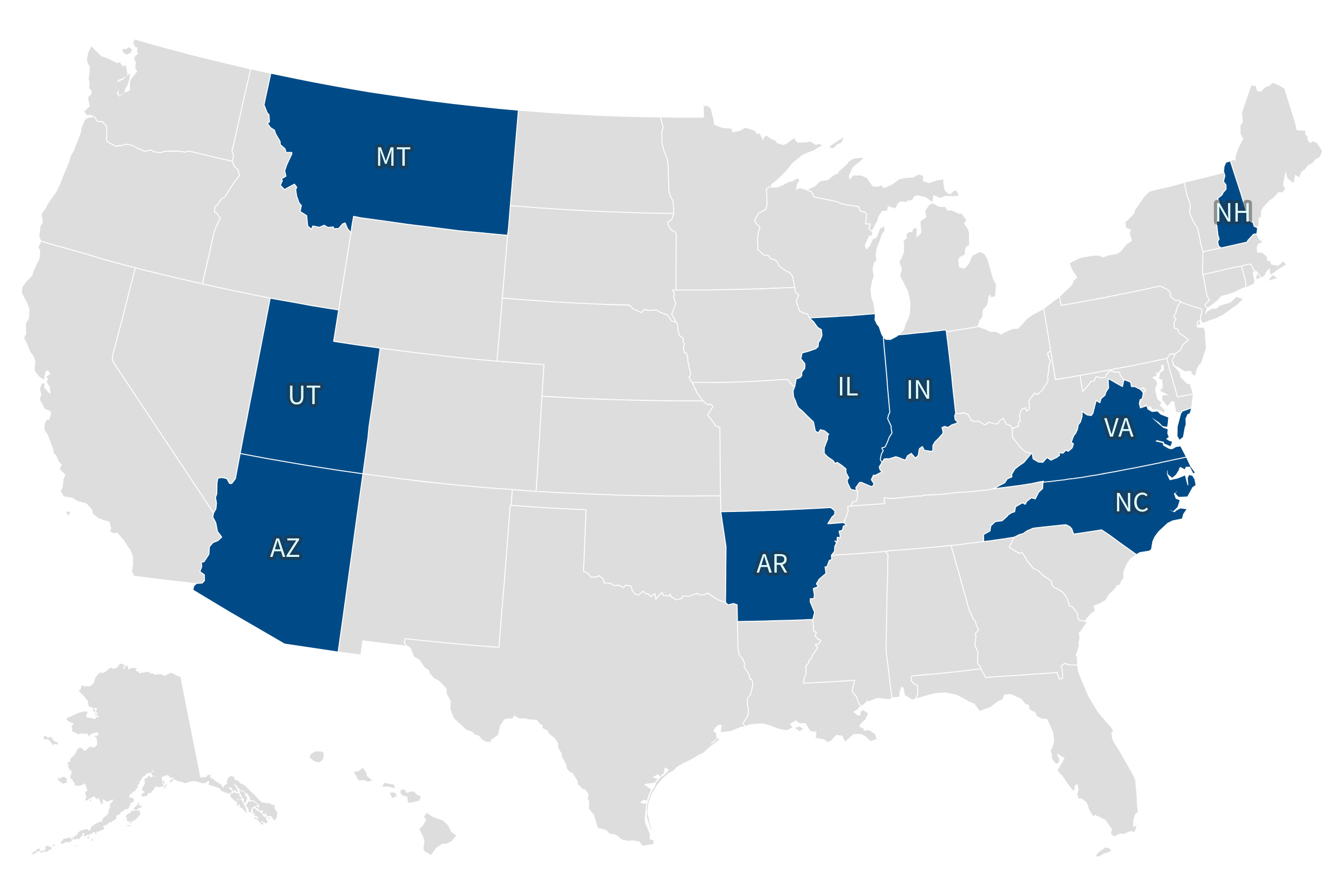

Ballad Health was created in 2018 after Tennessee and Virginia officials waived federal anti-monopoly laws and approved the nation’s biggest hospital merger, based on what’s called a Certificate of Public Advantage, or COPA, agreement. Ballad is now the only option for hospital care for most of the approximately 1.1 million people in a 29-county region at the nexus of Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina.

In the years since, there have been multiple signs of discontent with and within Ballad hospitals. In 2019, protesters gathered daily for eight months outside Holston Valley to oppose the closure of the neonatal intensive care unit and the downgrading of a trauma center. (Ballad has said the NICU closure was necessary and benefited patients, and a study published this year said the trauma changes saved lives.)

In 2020, Bristol Regional Medical Center CEO Greg Neal resigned after it was discovered he made the initial incision in a heart surgery despite not being a doctor, according to Tennessee state records. (Levine said in his interview that the resignation shows Ballad is holding employees accountable.)

In 2022, 14 cardiologists signed a letter warning of “severe limitations” in the Bristol Regional cardiac catheterization lab that were affecting patient safety and delaying procedures for weeks or months. (Ballad said in a letter to the Tennessee government that it worked with the cardiologists, who it said were partly to blame, to make the lab more efficient.)

In 2023, Ballad Health was ranked last among 200 large health care organizations in an analysis of nurse satisfaction published by an MIT business magazine. (Levine dismissed this analysis as unscientific.) This year, the Federal Trade Commission cited Ballad as a cautionary tale while opposing a similar hospital merger under consideration in Indiana, and a longtime Kingsport doctor took a parting shot at Ballad in his obituary. (Ballad declined to comment on either topic.)

And in August, the widow of a Tennessee sheriff filed a lawsuit alleging that Ballad caused her husband’s death and intentionally understaffed hospitals “to save money.” Brenda Tester, the wife of Johnson County Sheriff Eddie Tester, alleged in that lawsuit that Ballad put her husband on blood thinners and then gave him an unnecessary liver biopsy, causing “life ending internal blood loss” that led to “his cardiac arrest and ultimately his sudden death.”

Ballad has yet to respond to the Tester lawsuit in court. Levine said in his interview that the doctors who treated the sheriff were not employed by Ballad but merely contracted to work in its hospitals.

Some of Ballad’s most determined critics are family members of Anton Maki Jr., a former Holston Valley doctor who returned to the hospital as a patient in February. The family has filed complaints with multiple Tennessee agencies and the federal government and provided emails to KFF Health News showing that Tennessee is investigating Maki’s case.

In an interview and in those complaints, Maki’s family members allege Holston Valley gave Maki improper treatment, even though his symptoms and lab tests made it obvious that he was having a serious heart attack that required urgent attention.

The improper care did “permanent damage” to Maki’s heart, the family’s complaints allege. That damage required him to have a permanent mechanical heart pump surgically implanted at a non-Ballad hospital, said one of his daughters, Alexandra Maki, who is a surgeon in Kentucky. She said her father died after a fall three months later while still in a weakened state.

Alexandra Maki said that her father had been alarmed by the Ballad monopoly for years but that she didn’t fully appreciate his warnings until she witnessed his care at Holston Valley firsthand.

“I filed these complaints because it is my duty as a doctor to report what I saw,” Alexandra Maki said. “That was not care. It is a facade of a hospital. It is a well-oiled death machine.”

KFF Health News reporter Samantha Liss contributed to this article.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.