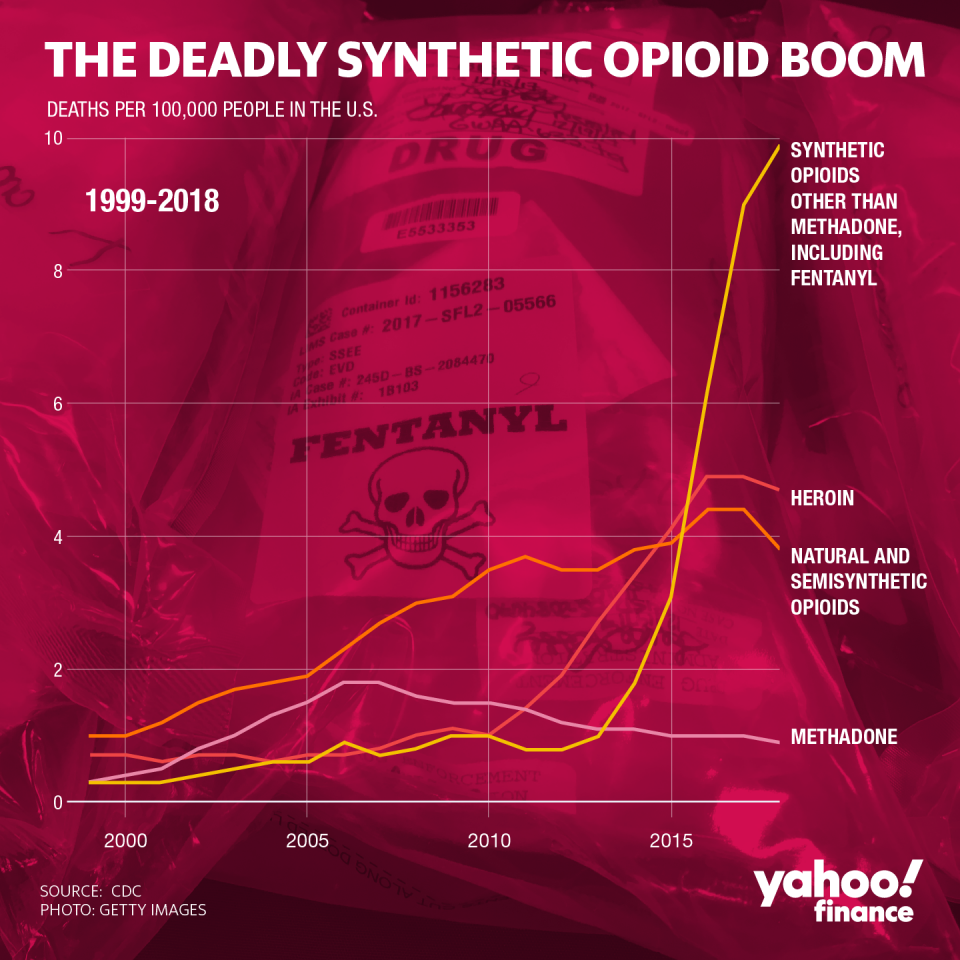

I am the mother of four, but addiction is my ever-present extra child. My grandparents died of alcoholism. My father-in-law did, too. My 43-year-old brother died of a heroin overdose in May. He became addicted after taking prescribed OxyContin following an appendectomy.

When my 13-year-old daughter needed hernia surgery as my brother was hitting rock bottom, it wasn’t the operation I feared. It was the opiates that would be part of her recovery. A 2018 study in the journal Pediatrics reported “persistent” opiate use by nearly 5 percent of patients age 13 to 21 following surgery, as compared to 0.1 percent in the nonsurgical group.

I wanted to figure out a way to help my daughter through the pain without resorting to using opiates.

Days before my daughter’s operation, our family devised a pain protocol based on what we learned from a popular TEDtalk byJohann Hari, a journalist who believes that people avoid addiction through “bonds and connections.”

He cites a study comparing two groups of rats. One group lived alone in cages, with only food, water and water laced with heroin. Those rats became addicted and quickly died. The other group lived in what Mr. Hari called “Rat Park.” They had treats, activities and interaction with other rats. They chose the plain water over the heroin water. They thrived, despite the presence of an addictive substance.

The message I took from it was that affection and connection might help reduce my daughter’s pain. If we surrounded her with comfort, maybe she wouldn’t need the drugs at all.

Our pain protocol included my daughter’s favorite movies, books and foods. We made a list of relaxing activities that build oxytocin: braiding hair, massage, cuddling and wearing cozy clothes. We listened to her fears. As a distance swimmer she could tolerate discomfort, but she was afraid of the unknown of surgical pain. We agreed to bring home whatever pain medication was prescribed, but to avoid using it if possible.

At the hospital, my daughter changed into a pink cotton gown, dotted with lambs and rainbows. I smoothed her hair as a tech struggled to pin an IV into the back of her hand.

“It hurts, Mommy,” she pleaded. “I’m scared.”

A nurse offered a thimble of liquid Xanax to help ease her anxiety. She looked to me for permission, then nodded her head yes. Moments later I witnessed a powerful transformation from fear to nonchalance. She waved goodbye as a team wheeled her bed around a corner. I thought of previous outpatient procedures my children had faced: tubes in the ears, a meniscus tear. I was never given instructions about alternative pain management and I didn’t think to ask. The difference, now, was that my brother was an addict. What if I gave my children pain pills and they became addicted too?

Three hours later the surgeon breezed through the waiting room doors. The hernia was deeper than expected, he reported, and she would be in considerable pain tomorrow.

In the recovery room, my daughter lay propped up in bed, sucking on a frozen rocket pop. “Mama,” she said drowsily. “I’m all done.” She battled to keep her heavy eyelids open. The ice pop melted upright in her hand.

I thought of my brother, nodding off on a family ski vacation; in a parked car waiting for an oil change; during a children’s egg hunt on Easter Sunday.

While my daughter slept, a discharge nurse told me how to change her dressing and watch for fever. Then she explained how to “stay on top” of the pain with a prescription for 44 Oxycodone tablets. My jaw tightened.

“I don’t want to give this to her,” I said, shaking my head at my own memories.

The busy hallway went silent, except for the alarm of an empty IV drip.

“This is like heroin to me,” I said. “My brother is addicted.”

The nurse looked away. “My daughter too,” she said, and began to cry. “She won’t stop. I had to kick her out.”

We exchanged the mournful words of opiate families: “It’s everywhere.”

“Is this all for me?” she asked quietly. She collapsed, smiling, into the stack of duvets on the sofa.

The anesthesia kept the edge off the initial pain. My daughter dozed while we watched episodes of “MasterChef Junior.” That night, my husband carried her to bed, then I slept beside her, alternating Tylenol and ibuprofen. In the morning, I inquired about her discomfort, hoping she wouldn’t ask for a pill.

“It’s just annoying,” she said.

“Annoying like you’re suffering?” I asked.

“Annoying like can I have ice cream for breakfast?”

“Coming right up,” I said. I offered her our specialty of the house: mint chip and a side of Advil. That day, nestled in our sofa oasis, we nibbled from a wooden bowl of buttered popcorn mixed with M&Ms. While surviving all three “High School Musicals,” I stroked her skin, smoothed her hair and praised her bravery. We played Uno, and worked on a puzzle. Greeting cards and balloon bouquets came in from friends and teachers. The principal called. Not once did she complain of intolerable pain.

She winced gingerly when she wanted to flip sides on the couch. We assisted her so that she wouldn’t use her abdominal muscles.

The discharge nurse had told us that walking would speed recovery, so we pretended her stuffed animals were babies and carried them on laps around the first floor of our house.

By day three, she didn’t even want the over-the-counter medication.

“I’m good,” she said. “I don’t need it.”

I felt a mixture of relief and rage. Why were we sent home with so many pills? Without my brother’s experience, I might have given all of them to her.

Her recovery was so quick that it became hard to keep her quiet. On day four I found her teetering on the back of the sofa, arms wide, like she was walking a tightrope.

“Have you lost your mind?” I snapped. “Get down from there!”

“Mom, I’m training,” she protested. “Pain doesn’t bother me so I’m practicing for the military. I made the sofa into an obstacle course.”

As I tucked her back under a blanket, I thought of the twists, turns and pressures my children will inevitably face in their adult lives. My daughter’s resilience has given me reason to hope. Together we are defying our family heritage.

This article first appeared here at the NYTimes.com

Jennie Burke is a writer who lives in Baltimore.