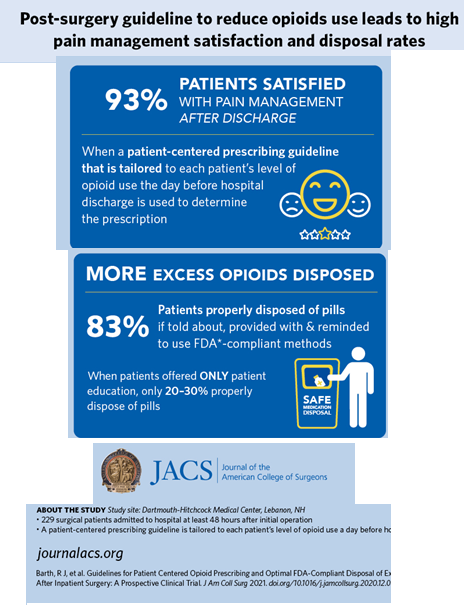

A prescribing guideline tailored to patients’ specific needs reduced the number of opioid pills prescribed after major surgery with researchers reporting a greater than 90 percent patient satisfaction rate with pain management and the highest compliance rate to date with appropriate disposal of leftover pills. The study was selected for the 2020 New England Surgical Society Program and published as an “article in press” on the website of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) in advance of print.

The researchers focused on a post-surgery opioid prescribing guideline developed by surgeons at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H. The guideline is based on the number of opioids patients take on the day before they are discharged from the hospital.

Lead study author Richard J. Barth Jr., MD, FACS, section chief of general surgery, explained that the guideline recommends discharging patients with no prescription for opioids if they have taken no opioids on the day before; 15 pills if they have taken one to three pills; and 30 pills if they have had four or more pills.

“This guideline was designed to satisfy the pain management needs of about 85 percent of patients,” said Dr. Barth, who led a previous study published in JACS in 20181

that proposed the guideline and showed that the number of opioids taken the day before discharge was the best predictor of how many opioids patients used after discharge.

The 2018 study involved only general surgery procedures, whereas the latest study included a broader cross-section of surgery: general surgery, as well as colorectal, gynecological, thoracic, and urological operations.

“In this new prospective study we found that 93 percent of patients had their post-surgery opioid needs satisfied,” Dr. Barth said of the most recent JACS study.

“This finding means that this guideline can be used for a wide variety of operations to guide surgeons on how many opioids to prescribe when sending patients home after surgery.”

Researchers consider patient’s perception of pain

This study is unique because it’s a prospective one of a post-surgery pain management guideline that takes into account an individual patient’s perception of pain. A prospective study enrolls patients before they’ve achieved the study outcome—in this case, an operation and their opioid use afterward—whereas a retrospective study evaluates outcomes after the fact. Other guidelines, which base the number of opioids prescribed solely on the operation that was performed, do not take into account individual variations in patients’ responses to pain. Minimizing opioid use among surgical patients is an important strategy for medicine because studies have found that up to 10 percent of patients who have undergone surgery, but have not used opioids before, may go on to become chronic opioid users.2

Study details

The study enrolled 229 patients admitted to the hospital for at least 48 hours after their initial operation. Upon discharge, patients received prescriptions for the non-opioid medications acetaminophen and ibuprofen, as well as opioids based on the guideline. Researchers used a protocol that deviated slightly from the post-discharge opioid prescribing guideline:

Patients who used no opioids—calculated as zero oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME)—on the day before discharge were sent home with five oxycodone 5-mg pill equivalents (PEs)

Patients who used up to 30 MME received 15 PEs

Patients who used 30 MME or more received 30 PEs

The lower the opioid usage was before hospital discharge, the higher the level of patient satisfaction with pain management: 99 percent of those in the zero-MME group reported satisfaction, as did 90 percent in the middle MME group, whereas 82 percent in the 30-plus MME group did so (P=0.001).

Despite being given an opioid prescription, 73 percent of the zero-MME group used no opioids at home, and 85 percent used two pills or less.

Surgeon’s role in minimizing opioid use

Dr. Barth noted that surgeons play a pivotal role in minimizing opioid use in their patients by setting expectations for pain management. That discussion involves letting patients know they are likely to be discharged with either no opioids or a small amount based on their opioid use on the day before they go home. “Explain to the patient, ‘We’ve studied this issue; we’ve figured out how many opioids you are likely to need,’” he said.

“The other part of that discussion involves letting patients know that they should expect some pain, that our goal isn’t to get rid of every last bit of their pain,” he added. “That was something that surgeons tried to accomplish years ago, but that’s not what we’re aiming for now. A low level of discomfort is acceptable, and patients need to have that expectation.”

That process also involves prescribing, not just recommending, over-the-counter non-opioid analgesics. “By prescribing non-opioid analgesics the surgeon sets the expectation that they should be used,” he said. “It’s a big difference if a surgeon prescribes non-opioid analgesics compared with just recommending that a patient take acetaminophen or ibuprofen that they might have at home.”

He added, “In this study, 95 percent of the patients took either acetaminophen or ibuprofen and 70 percent took both, whereas in previous studies1 where we had just recommended that they use them, 85 percent reported taking one or the other, but only 20 percent reported taking both.”

Opioid disposal rate soars with surgeons’ input

Proper disposal of unused pills is another key component of responsible opioid management. In this study, 60 percent of patients had leftover pills. “We worry about unused pills because those pills could be used by that individual patient and might predispose them for long-term or chronic use,” Dr. Barth said. “Those excess pills could also be diverted to others and perpetuate opioid misuse in the community.”

The Dartmouth-Hitchcock investigators employed several strategies to encourage patients to properly dispose of leftover pills. In addition to educating patients about the potential for opioid misuse and diversion, one strategy was to install a drop box for leftover pills in the institution’s pharmacy, located near the surgeons’ outpatient offices. A phone call before the post-surgery follow-up appointment also reminded patients to bring their unused pills with them to dispose. “These are easily actionable items that can really impact the disposal of excess opioids,” Dr. Barth added.

When these strategies were employed, 83 percent of patients disposed of their excess opioids using a method that complies with Food and Drug Administration recommendations. This rate is substantially higher than rates of disposal in the 20-to-30 percent range reported by other investigators who relied on patient education alone.3 Fifty-one percent of the patients who disposed of their excess opioids used the drop box in the hospital pharmacy, while 28 percent used a drop box in a police or fire department and 21 percent used other FDA-compliant methods of disposal. A total of 2,604 pills were prescribed in the study; only 187 of them (7 percent) were kept by patients.

This article first appeared at Facs.org here