When patients walked into Planned Parenthood clinics, a consumer data company sold their precise locations to anti-abortion groups for targeted ads.

When patients picked up prescriptions for testosterone replacement therapy, law enforcement retrieved their names and addresses without a warrant.

And when a father was arrested by immigration authorities, agents allegedly accessed his personal information from a medical clinic where he received diabetes treatment.

Progressive California lawmakers have proposed a number of bills aimed at bolstering privacy protections for women, transgender people, and immigrants in response to such intrusions by anti-abortion groups, conservative states, and federal law enforcement agencies as President Donald Trump declares the nation “will be woke no longer” and flexes his executive power to roll back rights.

Democrats have supermajorities in the state legislature, but even if they pass the proposals, they may first need to lobby one of their own: Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has noticeably tempered his once harsh criticism of Trump.

Last month, the Democratic governor issued a rare veto threat against a bill that would expand the state’s sanctuary law to limit cooperation between state prisons and federal immigration agents. And Newsom recently called transgender athletes’ participation in women’s sports “deeply unfair” on his new podcast with guest Charlie Kirk, a founder of the conservative group Turning Point USA. Newsom went on to tell Kirk that he had a “hard time with” the way the right talks about transgender people.

Billions of dollars are also on the line for California. Newsom visited the White House last month seeking unconditional aid for wildfire victims in Los Angeles, and the state relies on Washington for over 60% of its Medicaid budget, which is vulnerable to significant cuts under the GOP’s budget blueprint.

“California’s leaders have not been as aggressive, out of recognition that there are many things that the state needs federal cooperation on,” said Thad Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California-San Diego.

A Newsom spokesperson declined to comment on pending legislation. He has a track record of supporting abortion, transgender, and immigrant rights.

Since taking office, Trump has granted the Elon Musk-controlled Department of Government Efficiency — created through a Trump executive order — access to previously restricted data, including medical information, raising concerns that sensitive information could be exposed without proper safeguards.

The White House did not respond to requests for comment.

While most Americans are familiar with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, known as HIPAA, it offers only narrow protection for patients in health care settings. There’s no comprehensive federal law protecting data privacy.

Health care information has increasingly become a tool of surveillance and enforcement, and in states that have banned certain medical treatments or toughened immigration laws, vulnerable populations are at greater risk, said Suzanne Bernstein, a health privacy rights expert with the Electronic Privacy Information Center.

Progressive Democrats are concerned that personal information and people’s medical decisions could be used to monitor or criminalize patients, facilitate arrests in or near health care facilities, or jeopardize access to health care services.

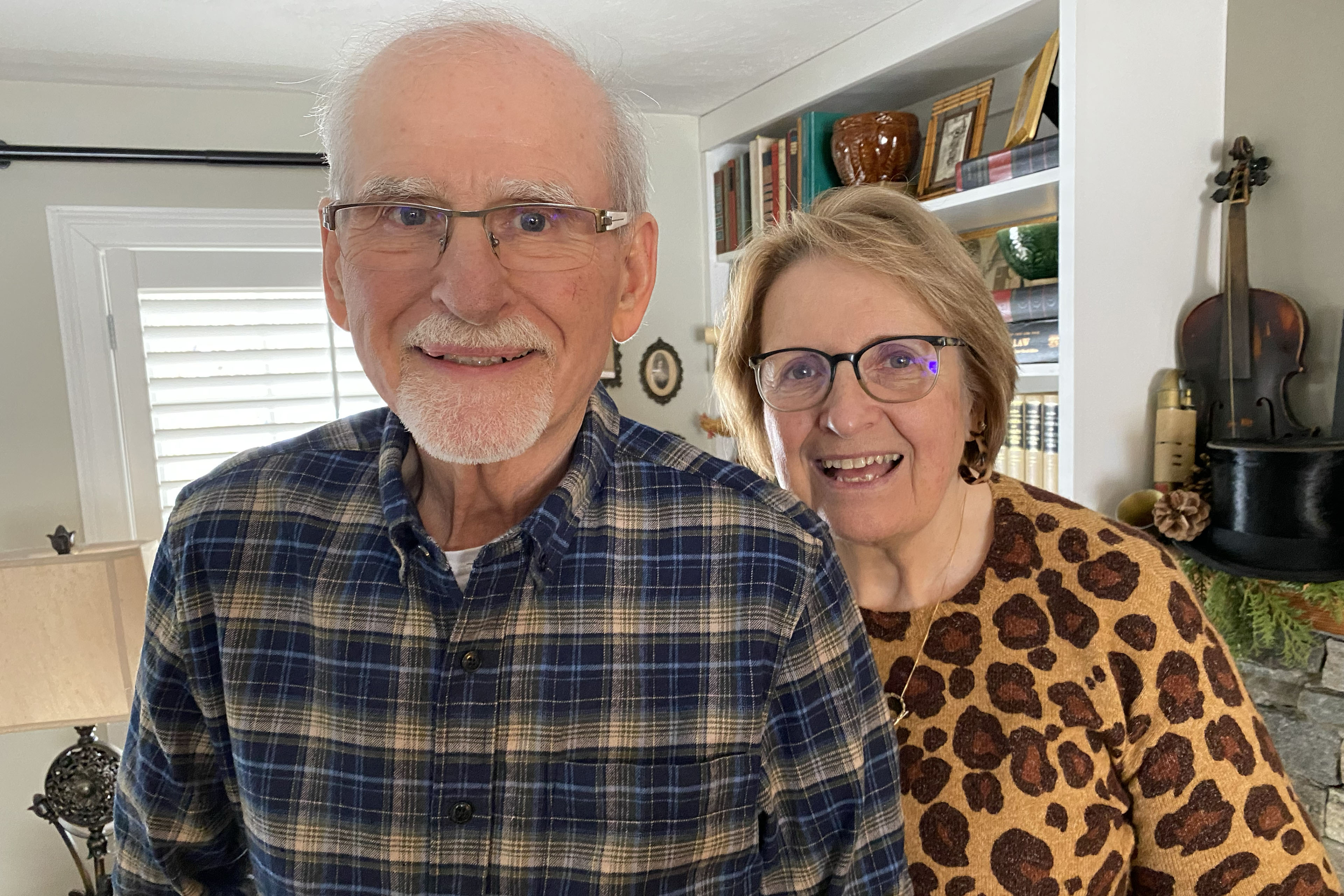

They and health privacy advocates say now is the time to shore up protections for the nearly 2 million immigrants living in California without authorization, the more than 200,000 transgender adults in the state, and thousands of people — living in the state or out of state — in need of abortion care in California each year. Some of these laws could take effect immediately if signed.

“This is about making sure that people are able to access critical health care in California and to take the politics out of our hospitals and health clinics,” said state Sen. Jesse Arreguín, who hopes the governor would sign his bill to protect immigrants.

The bills are expected to be debated in Sacramento in the coming months.

Since the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion, anti-abortion groups have purchased location information from consumer data companies to target people seeking abortion care with anti-abortion ads. And authorities in states with abortion bans have used cellphone data to enforce laws beyond their borders.

A bill introduced by state Assembly member Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, AB 45, would make geofencing, the collection of phone location by data brokers, illegal around health care facilities that provide in-person services. It would also prevent reproductive health information collected during research from being disclosed in response to out-of-state requests.

Conservative organizations said the proposal would single them out by restricting their ability to inform women about alternatives to abortion, including services offered by crisis pregnancy centers.

“I think that could very well be a First Amendment violation,” said Jonathan Keller, president of the California Family Council, a statewide anti-abortion nonprofit. “It doesn’t seem like the bill would be prohibiting or putting any restrictions on a group like Planned Parenthood if they wanted to market or target to a local high school or college.”

So far this year, lawmakers in 49 states have introduced more than 700 anti-transgender bills, seeking to ban gender-affirming care, prohibit gender identity education in schools, or restrict transgender students from participating in sports, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker, a national research organization tracking bills affecting transgender people. Transgender adults represent less than 1% of the U.S. population.

And some states with bans or restrictions on gender-affirming care have been targeting health care data. In 2023, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis requested that Florida universities release data on the number of individuals who have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria or received treatment at campus clinics. That same year, Missouri’s Republican attorney general, Andrew Bailey, submitted 54 requests to one hospital seeking information about gender-affirming care procedures.

Trump has issued a series of executive orders to ban access to gender-affirming care for minors. Federal judges have temporarily blocked some portions of his orders.

To guard against other states that criminalize or ban gender-affirming care, California state Sen. Scott Wiener wants to expand current protections for minors to include adults.

His bill, SB 497, would require law enforcement to obtain a warrant to access state databases on gender-affirming care and make it a misdemeanor to release the data to unauthorized parties. It would also prohibit health care providers, employers, and insurers from releasing information about a person who seeks or obtains gender-affirming physical and mental health care to an agency or individual from another state.

“We want to make sure that we are as comprehensively as possible shielding trans people from hate emanating from the federal government, other states, and private parties,” Wiener said.

Keller countered that authorities in states with bans on abortion or gender-affirming care should have access to medical information as they investigate providers who could harm patients or coerce them into procedures against their will. He cited a lawsuit against Kaiser Permanente over a teenager who detransitioned after undergoing gender-affirming care. A 2015 survey found it was uncommon for people undergoing gender-affirming care to decide to permanently detransition.

“The only way that you’re able to uncover that level of widespread malpractice and malfeasance is if these health care records are able to be accessed,” Keller said.

The California Family Council plans to oppose both bills.

Earlier this year, Trump rescinded a long-standing policy of not making immigration arrests near hospitals, schools, or churches. The decision has providers fearful that Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents will disrupt their work at health facilities and prompt immigrants to skip medical care — for themselves or, of particular concern, their children.

Anticipating the move, California’s Democratic attorney general, Rob Bonta, issued guidance in December advising health care providers how best to respond if ICE comes to their doorstep. But while private entities are encouraged to follow these policies, only state-run facilities are required to adopt them.

“Some health care providers have implemented them, but not everyone has,” Arreguín said.

Arreguín’s SB 81 would require all health care facilities, including hospitals and community-based clinics, to follow state guidance to limit cooperation with immigration authorities. It would also prohibit providers from granting access to private areas or places where a patient is actively receiving treatment or care, unless there’s a warrant.

Another immigration bill, AB 421, would limit the sharing of local law enforcement information if agents plan to make an arrest within a one-mile radius of a hospital or medical office, a child care or day care facility, a religious institution, or a place of worship. California law enforcement has some discretion to share information with immigration agents when an individual has been convicted of a serious crime or felony.

Kousser said immigration is more complicated for California politicians than health privacy. Although a February poll by the Public Policy Institute of California found that 7 in 10 Californians think immigrants are a benefit to the state, Kousser said that lawmakers, especially those who won by narrow margins in contested districts, still have to make tough political choices.

Senate Republican leader Brian Jones, who represents a predominantly Democratic district in San Diego, is proposing to change California’s sanctuary policies to require law enforcement to share information with ICE when a person has been convicted of a serious crime.

“When these violent felons are released from local custody, they go right back into the communities that they came from to re-victimize those same immigrant communities,” Jones said.

But Jones acknowledged the need for nuance when it comes to health privacy.

“Look, the bottom line for me on this immigration reform in America is it needs to be humanitarian and it needs to make sense,” Jones said. “And so, if there are areas that we need to protect folks, it might make sense.”