by bob k

On May 31, 2011, Alcoholics Anonymous was dramatically altered, both in Toronto, Ontario and far beyond. In the short run, the changes produced were precisely as they had been intended to be. However, the long-term results were exactly the opposite of the goals of the crusaders seeking to purify Toronto AA.

Back in September of 2009, Beyond Belief, an agnostic AA group, had been formed in mid-town Toronto. It scooped up some members from nearby groups and garnered the enthusiastic support of many others. There was nothing surreptitious about the group’s operation. The intergroup’s listing linked to Beyond Belief’s personal page describing the prayerless meetings and posting, alongside the traditional steps, a secular interpretation of AA’s Twelve-Steps.

From the start, Beyond Belief was popular and successful. Within a few months, a larger room was needed and acquired. A second weekly meeting was added. At some point, a break-out room helped to accommodate the growing attendance. In September 2010, another nontraditional group, We Agnostics, was organized at a different location. Nonconforming newcomers were drawn to the secular format and experienced success not attained during previous forays into conventional meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Older members found a renewed passion, now freed from the unappealing options of having to “go along to get along” or staying silent.

Despite seemingly endless protestations that the organization is “spiritual not religious,” atheists, agnostics, and many others find Alcoholics Anonymous to be quite religious. Perhaps the heathens’ misunderstanding of the enormous difference between spirituality and religion comes from the unfortunate fact that the spiritual and the religious versions of the Lord’s Prayer contain precisely the same words. The broader definition of “religion” aligns closely with all that goes on in AA.

Rarely has any society been more attached to the status quo.

On May 31, 2011, the two agnostic groups were unceremoniously booted out of Toronto AA. The motion had prompted lively discussion but a separate motion to defer the vote to the following month was defeated. The anti-agnostic element was bloodthirsty and wanted their pound of flesh right then and there.

What happened in Toronto became a topic of conversation in many locales far afield from Toronto. “Experts” from Pittsburgh, Seattle, Topeka, and Jacksonville weighed in on the issue, undeterred by their complete lack of direct experience with the events: “Of course, they were delisted — they changed the steps. Delisting isn’t a big deal. A real AA group engaged in real 12-Step work doesn’t really need a listing.”

To be clear, the two Toronto agnostic groups were not simply delisted. They were disenfranchised. When a motion came in 2012 to revisit the issue, relist the groups, etc., Beyond Belief and We Agnostics could not speak for themselves nor could they vote for themselves. The Intergroupers had done all that they could within the limits of their power, but they tried to do more. They reached out to the General Service people pressing for further purging actions.

This was more than a delisting.

In the shortest of times, the website organized to advertise the meeting times and locations of the two non-religious AA groups morphed into aaagnostica.org. Seemingly nanoseconds later, the Toronto website had viewers from all over the globe. Some came to love and some came to hate. Others were merely curious. “What is agnostic AA? I’ve never heard of that.”

On June 22, webmaster Roger C. posted “Anarchy Melts,” essentially a condemnation of the delisting and disenfranchising actions of the Toronto Intergroup through the words of AA founder Bill Wilson: “Any two or three alcoholics gathered together for sobriety may call themselves an AA Group.” The assault on the oppressors continued. Groups facing Intergroup attacks in other regions weighed in with their stories. During the five-year period that the groups were out of Toronto AA, AA Agnostica acted as the voice of a growing movement.

When secular literature was published, AA Agnostica offered book reviews. History essays were presented, and satires ridiculed fundamentalists and their proclivity for inconsistency.

Agnostic AA was growing and there was a thirst for information about it. “How do I go about starting a secular meeting in my town?” It’s a delicious irony that the agnostic AA movement owes a debt of gratitude to Toronto Intergroup. Following the “Law of Unintended Consequences,” the intergroup crusaders’ efforts to purify AA led to the creation of the AA Agnostica website. It’s undeniable that the tremendous growth of AA’s secular movement has been significantly spurred by the material presented here.

There’s a tremendous amount of work involved in operating a busy website. When John S. of Kansas City agreed to take up the mantle, Roger C. planned to retire from active posting. Of course, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry. Activists have a hard time sitting back and viewing the action from a Lazy-Boy. The period of inactivity was brief. There followed five glorious years during which we had two marvellous websites, AA Beyond Belief and AA Agnostica.

John added podcasting and that’s his niche. He may have overloaded himself. For someone with a full-time job in the real world, it was all a bit too much, so he dropped the weekly essays, retiring AA Beyond Belief. As AA Agnostica winds down, we will soon have no such venue. Perhaps someone reading this today will be moved to take up the task.

We need a new website and webmaster.

A total of fifty-four articles by Bob K have been posted on AA Agnostica (those by Bobby Beach have a check mark –  ):

):

- Websites and The Growth of Secular AA (June 6, 2021)

- Courtenay Baylor (April 25, 2021)

- The Magical Mystery Cure (is coming to take you away) (February 7, 2021)

- The Virtual 2020 Secular AA Conference (December 20, 2020)

- “We’re Spiritual Not Religious.” “Oh, Please!!” (October 4, 2020)

- Sleight of Hand; Slight on “Real” Inclusivity (September 20, 2020)

- THUMPERTOWN THEATRE PRESENTS… Bill and Bob go to the Library (May 24, 2020)

- What If We Built It And Nobody Came? (May 13, 2020)

- The Underground Railroad (April 26, 2020)

- The One and Only Kool-Aid (February 23, 2020)

- Tales of Spiritual Experience (January 19, 2020)

- The Rainbow Group (January 8, 2020)

- WRITING the BIG BOOK: The Creation of AA (November 17, 2019)

- Unintended Consequences (March 31, 2019)

- We Are Diversity (March 20, 2019)

- Freaken Big Book Fundamentalists Hate Freaken Everything (February 24, 2019)

- The Sad Tale of the Founder of Moderation Management (January 6, 2019)

- Bill W, LSD and AA Spirituality (November 18, 2018)

- Lord’s Prayer Threatened – Fundies go Wild (June 28, 2017)

- A Manual for Alcoholics Anonymous (June 4, 2017)

- The Kawartha Freethinkers (May 21, 2017)

- The Search for Self-Esteem (March 30, 2017)

- The Watering Down of AA (March 16, 2017)

- Remembering Ernie Kurtz (January 19, 2016)

- Carl Gustav Jung (June 28, 2015)

- Anne Smith (April 26, 2015)

- Jim Burwell (March 22, 2015)

- Dr. Bob – Part Two (Akron-Style AA) (January 25, 2015)

- William Duncan Silkworth (October 22, 2014)

- Lois Wilson (October 5, 2014)

- Bill Wilson and Other Women (October 1, 2014)

- Sylvia K. – First Lady of Chicago AA (September 14, 2014)

- William James and AA (August 24, 2014)

- Slaying the Dragon (July 2, 2014)

- Alcoholism – What’s It All About? (May 25, 2014)

- Twelve Steps to Psychological Good Health and Serenity (April 23, 2014)

- Dr. Bob, AA Co-Founder – Part One (March 30, 2014)

- Young Bill Wilson – Part Two (December 1, 2013)

- Young Bill Wilson – Part One (November 24, 2013)

- Frank Buchman and the Oxford Group (November 3, 2013)

- Charles B. Towns (October 6, 2013)

- Clarence Snyder: Almost Co-Founder (September 15, 2013)

- Anonymity in the 21st Century (April 21, 2013)

- Marty Mann and the Early Women of AA (April 14, 2013)

- Edwin Throckmorton Thacher (Ebby) (February 3, 2013)

- Christmas, Christians, Lepers, and Alcoholics (Revisited) (December 23, 2012)

- Twentieth Century Influences on AA (November 18, 2012)

- Short of a Game Changer – Appendix II (October 21, 2012)

- God As We Understood Him (June 17, 2012)

- Heathens, Spies, Websites, Water-boarding & Carrot Cake (April 1, 2012)

- AA in the 1930s: God As We Understood Him (February 8, 2012)

- Does AA Need Religion: Agnostics on CBC Radio (January 29, 2012)

- Our Father Who Art Not in Public Schools (January 15, 2012)

- Christmas, Christians, Lepers and Alcoholics (December 29, 2011)

And here are articles by Bob posted on the AA Beyond Belief website (again with a check mark –  – for those by Bobby Beach):

– for those by Bobby Beach):

- Pandemics, Zoom and Happy Heathens (October 25, 2020)

- Sam Shoemaker (September 6, 2020)

- Richmond Walker (July 12, 2020)

- Fundamentalism’s Foibles and Follies (May 31, 2020)

- Billy Sunday (March 8, 2020)

- A Heathen Looks at the Twelve Steps (January 19, 2020)

- Powerlessness and Other Stuff (December 8, 2019)

- AA Incorporated (November 10, 2019)

- Our Perfectly Imperfect AA Founder (October 27, 2019)

- Lordy! Lordy! Lordy!!! (August 11, 2019)

- New Thought and AA (July 7, 2019)

- Dr. Benjamin Rush (June 16, 2019)

- Rowland Hazard (May 26, 2019)

- Florence Rankin (March 17, 2019)

- Ebby Thacher – An Unhappy Life (February 3, 2019)

- Selling AA – Early Publicity (May 6, 2018)

- Not Just the Washingtonians Part II (April 30, 2017)

- Toronto Agnostic AA Groups Win Fight for Inclusion (February 12, 2017)

- Floggings, Strychnine, Leeches, and Worse (November 13, 2016)

- Not Just the Washingtonians (April 17, 2016)

- Henrietta Sieberling (March 2, 2016)

- THE COMMON SENSE OF DRINKING | Richard R. Peabody (1931) (February 2, 2016)

- Willard Richardson and the Rockefeller People (February 3, 2016)

- Remembering Ernie Kurtz (January 19, 2016)

- Positive Affirmations and the Placebo Effect (January 17, 2016)

- The Washingtonian Society (January 6, 2016)

- The Fraud that is AA Fundamentalism (January 3, 2016)

- AA’s Sister Ignatia (December 2, 2015)

- ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS UNIVERSAL EDITION, By Archer Voxx (November 18, 2015)

- The LSD Experiments (October 21, 2015)

- Jerry McCauley – The Water Street Mission (October 14, 2015)

- Henry Parkhurst (October 7, 2015)

bob k is the co-founder of the Whitby Freethinkers Group just east of Toronto. He is the author of Key Players in AA History, published in 2015. A second edition will soon be published.

bob k is the co-founder of the Whitby Freethinkers Group just east of Toronto. He is the author of Key Players in AA History, published in 2015. A second edition will soon be published.

Two more books by bob are in the works – The Road To AA: 1620-1935 and The Secret Diaries of Bill W, a book which will be an intriguing biographical fiction of the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous.

The post Websites and The Growth of Secular AA first appeared on AA Agnostica.

![Do Tell! [Front Cover]](https://nrdblogs.nationalrehabdirectory.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Do-Tell-Full-Blue-Front-Cover-200-FRAMED.jpg) This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

This is a chapter from the book: Do Tell! Stories by Atheists and Agnostics in AA.

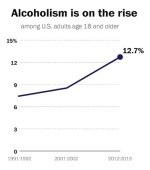

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.”

Americans would be justified in treating alcohol with the same wariness they have toward other drugs. Beyond how it tastes and feels, there’s very little good to say about the health impacts of booze. The idea that a glass or two of red wine a day is healthy is now considered dubious. At best, slight heart-health benefits are associated with moderate drinking, and most health experts say you shouldn’t start drinking for the health benefits if you don’t drink already. As one major study recently put it, “Our results show that the safest level of drinking is none.” Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.

Meanwhile, the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which is listed as the top campaign contributor to political candidates in the “beer, wine, and liquor” category by the Center for Responsive Politics, has lobbied for a bill that would, among other things, reduce excise taxes on beer and spirits.