Fifty Chosen Articles:

Number Thirty.

The last of the three international secular AA conferences.

Originally posted in September 2018.

The history and growth of Secular AA over the past decade.

By Carolyn B.

I am a relative newcomer to Secular AA (just over one year) and on attending the International Conference of Secular AA in downtown Toronto at the Marriott Hotel this past weekend I experienced the same feelings of joy, relief and of having finally found my people that I experienced in my first meeting of secular AA.

With 268 delegates from around the world – including countries such as Great Britain, France, Australia and Poland – the conference was filled with a sense of fellowship and lively debate. Secular AA is alive, vibrant, willing to consider change, tackle difficult questions and to consider how we will move into the future. The theme and focus of the conference was on inclusion and diversity.

There were many topics discussed in the conference plus there were concurrent sessions. There were seven panels held in the main ballroom. And a total of 30 workshops! I could not attend as many as I would have liked. Topics ranged from online meetings, anonymity, LGBTQ meetings, atheist beliefs and secular AA. Other sessions included starting Secular groups and organizing regional conferences, women’s issues in AA, and Secular Al-Anon to name a few. Here are some titles of the panels and workshops (you can see all of them here, ICSAA Agenda):

- History of Secular AA

- She Devils AA Meeting

- Emotional Sobriety: The New Frontier

- Are Atheist Thumpers Dividing Secular AA?

- The Biology, Psychology and Philosophy of Spirituality

- How to Start a Secular AA Meeting

- My Pet is Step 2

- Relationship Repair in Recovery

There were several sessions that stood out for me and may be of interest to others. They were on the themes of recovery and spirituality.

First, recovery. There was considerable discussion on what recovery means and as you and I know many feel it is a process rather than an actual state. There were interesting discussions on what has been found to be helpful in recovery; that quitting drinking is not enough as we all know. “Recovery Capital” was the name of a wonderful workshop conducted by Dr. Ray Baker, from British Columbia. Recovery Capital is defined as “the volume of internal and external resources that can be drawn upon to initiate and sustain recovery from addiction” (Granfield & Cloud 1999). This involves focusing on one’s physical, social, cognitive, behavioural and spiritual life. Of course this makes sense for those of us who are addicted.

Second, spirituality. There was a spectrum of opinion expressed by atheists on the place of spirituality in Secular AA. Some of the more militant atheist members feel that using the word spirituality in the secular groups makes us more like traditional AA and they oppose this. Others have a more broad concept of spirituality. Both atheists and agnostics share ideas of spirituality as not being religious; but, rather they used such terms as “ethical spirituality”, “self – transcendence” and “transcendence”. I offer these ideas for your consideration.

One of the people at the conference was Jon W, the senior editor of the AA Grapevine. Jon was part of a panel organized by Roger C on The History of Secular AA. The Grapevine has put together a book in which “Atheist and agnostic AA members share their experience, strength and hope”. The book contains 43 stories by nonbelievers in AA previously published by the Grapevine, the first in May 1968 and the most recent in October 2016.

One of the people at the conference was Jon W, the senior editor of the AA Grapevine. Jon was part of a panel organized by Roger C on The History of Secular AA. The Grapevine has put together a book in which “Atheist and agnostic AA members share their experience, strength and hope”. The book contains 43 stories by nonbelievers in AA previously published by the Grapevine, the first in May 1968 and the most recent in October 2016.

Although it was not yet officially published, 250 copies were made available at the conference. The title of the book, One Big Tent, perfectly reflects the theme of the conference, diversity and inclusiveness, and is an important part of the contemporary history of the secular movement within Alcoholics Anonymous!

I need as well to report that there were three excellent keynote speakers at the conference. The first one to speak was Dr. Vera Tarman. Her topic was “More was my Higher Power”. In the panel on spirituality she also talked about the biology of spirituality, which was fascinating, to say the very least.

The second speaker was Deirdre S from New York who gave a talk entitled “The Cross-Addicted Mind: How Obsessive Use of Substances and Behaviors Fuels Alcoholism”. She also spoke at the Austin convention and you can read her talk here, A History of Special Interest Groups in AA.

And finally, the talk “AA: do we need God to make it work? A medical-scientific analysis” was presented by Dr. Ray Baker, who also did the workshop on Recovery Capital. He is writing a book about addiction, the working title is Recovery Medicine, and I really look forward to it being published!

As mentioned previously there were many ideas and questions raised throughout the conference. Questions that I need to think about and you may also want to consider are:

- Do we need to use the Secular 12 Steps in our meetings?

- Do we ever need the 12 steps at all in Secular AA?

- How do we make our meetings open to youth?

- Are there specific readings that we can use in Secular AA that are not part of traditional AA? If so what would they be?

- How closely affiliated do we want Secular AA to be with Traditional AA?

These are some of the highlights, ideas and questions that were discussed at the conference. I present them here for your consideration.

And while there was a stimulating and exciting diversity of opinion at the conference, there was also agreement on key issues. At the membership business meeting on Sunday morning two statements were adopted unanimously by those at the conference.

The first is our mission statement, the mission of secular AA:

Our mission is to assure suffering alcoholics that they can find sobriety in Alcoholics Anonymous without having to accept anyone else’s beliefs or deny their own. Secular AA does not endorse or oppose any form of religion or belief system and operates in accordance with the Third Tradition of the Alcoholics Anonymous Program: “The only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking”.

The second is our vision statement:

Secular AA recognizes and honors the immeasurable contributions that Alcoholics Anonymous has made to assist individuals to recover from alcoholism. We seek to ensure that AA remains an effective, relevant and inclusive program of recovery in an increasingly secular society. The foundation of Secular AA is grounded in the belief that anyone – regardless of their spiritual beliefs or lack thereof – can recover in the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous. Secular AA exists to serve the community of secularly-minded alcoholics by supporting worldwide access to secularly formatted AA meetings and fostering mutual support within a growing population of secularly-minded alcoholics.

The conference was an opportunity to think about the larger issues facing Secular AA and my place in it. It was a very exciting conference for me. While the conference was intellectually stimulating, in no way does it take away the importance from what we do in our groups each week. For me, our group provides safety, fellowship, an opportunity to learn from others and to share my issues on my path to recovery. While the conference was stimulating, I am so grateful I have my group!

Carolyn B is a retired educator. She was initially involved in traditional AA but always found the “god” part not true to her beliefs. On moving to Hamilton, Ontario she discovered the We Agnostics Group. She has been an active and grateful member ever since.

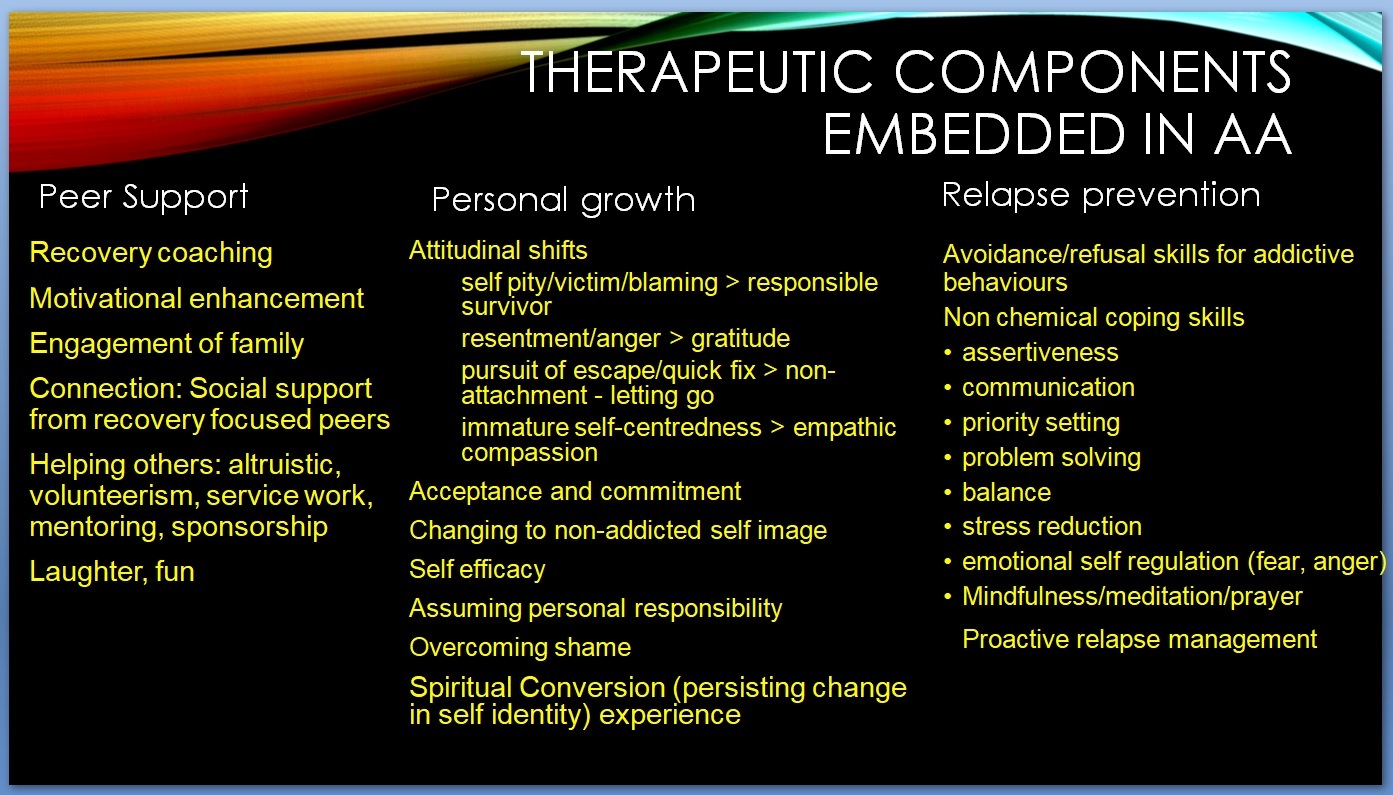

During his workshop at the conference, Dr. Ray Baker shared this slide that lists the ways in which recovery can be achieved and supported within Alcoholics Anonymous:

For a PDF of this article, click here: The 2018 International Conference of Secular AA.

The post The 2018 International Conference of Secular AA first appeared on AA Agnostica.

Rader specifies four fundamentals of recovery: self-direction, abstinence, physical health maintenance, and cognitive-behavioral transformation. Sticking with his clear and concise style, he gives the reader a thorough explanation of each fundamental and stresses that they are interrelated and that each one needs to be dealt with on a continual basis. This of course begs the question “just how am I supposed to do this?”

Rader specifies four fundamentals of recovery: self-direction, abstinence, physical health maintenance, and cognitive-behavioral transformation. Sticking with his clear and concise style, he gives the reader a thorough explanation of each fundamental and stresses that they are interrelated and that each one needs to be dealt with on a continual basis. This of course begs the question “just how am I supposed to do this?”