Note: “An Arm and a Leg” uses speech-recognition software to generate transcripts, which may contain errors. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

Dan: Hey there. So, awards season has already started …

Nikki Glaser, Golden Globes host: Good evening! And welcome to the 82nd Golden Globes, Ozempic’s biggest night.

Dan: OK, I did not watch the Golden Globes this year. But there is an awards show that’s made basically just for nerds like me.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Hello, everyone, and welcome to the eighth annual Shkreli Awards.

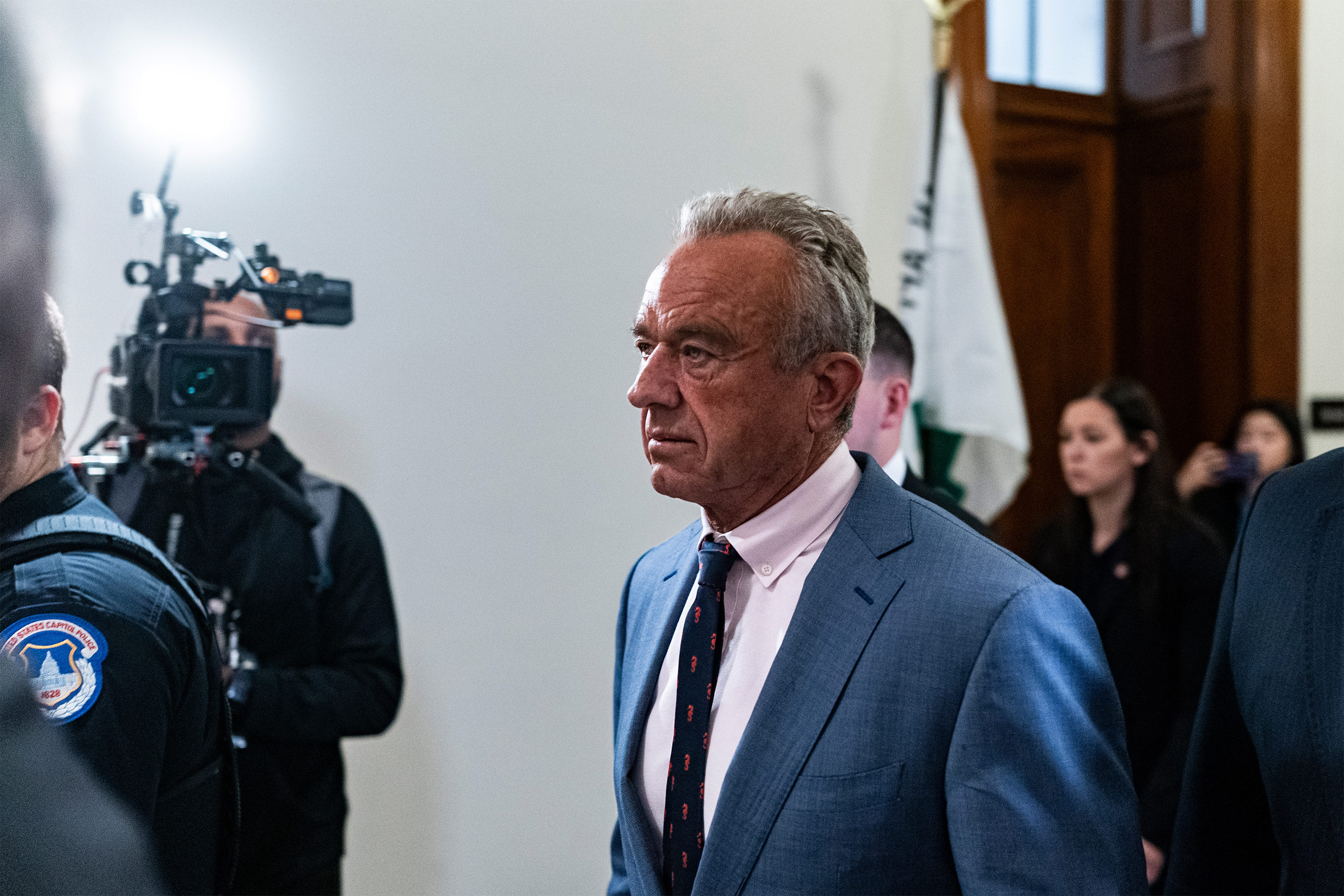

Dan: The Shkreli Awards! Named after the “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli. Remember him?

He became famous — infamous — in 2015, when a company he ran took over the making of an old drug called Daraprim. Old, old. Introduced in 1952, but it later became used to prevent a form of pneumonia that people with HIV can develop.

So Martin Shkreli jacked up the price — from thirteen-and-a-half dollars a pill to seven hundred and fifty bucks. Rings a bell, right? So, who gives out awards named after that guy?

Answer: A health care think tank called the Lown Institute. One of their big recent projects was ranking nonprofit hospitals by how much they do to “earn” their tax exemptions, for instance, by giving out charity care. The institute’s president, Dr. Vikas Saini, hosts the awards ceremony.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): So if this is your first time at the Shkreli Awards, this is our top 10 list of the most egregious examples of profiteering or dysfunction in health care.

Dan: I’m telling you: this is an awards show for nerds just like me. In fact, it’s also kind of a celebration of nerds kind of like me. Each of the awful stories these awards highlight was dug up and brought to light by … journalists.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): So this year, the journalists behind these stories will be receiving a Shkreli Reporting Award. And I have one in my hand here.

Dan: It’s a bobble head: White guy in a black suit — Clark Kent without the glasses – and it’s in a display box that says 2024 Shkreli Award. Someday, I hope the reporting we do here earns us one of these. The ceremony was held January 7. We’ll bring you some highlights — I mean, is it a highlight when you’re giving awards for the worst things? Well, let’s just say they were some of the most entertaining stories.

And we’ve got some reflections from a conversation I had with Dr. Saini the next day. The ceremony itself wasn’t fancy — just a Zoom presentation — but we’re gonna dress it up a little bit, so it sounds like other awards shows, with a big crowd, and a stage …

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): All right, so. Without further ado, let’s do the countdown. The 2024 Shkreli Awards. Brace yourselves. Here we go.

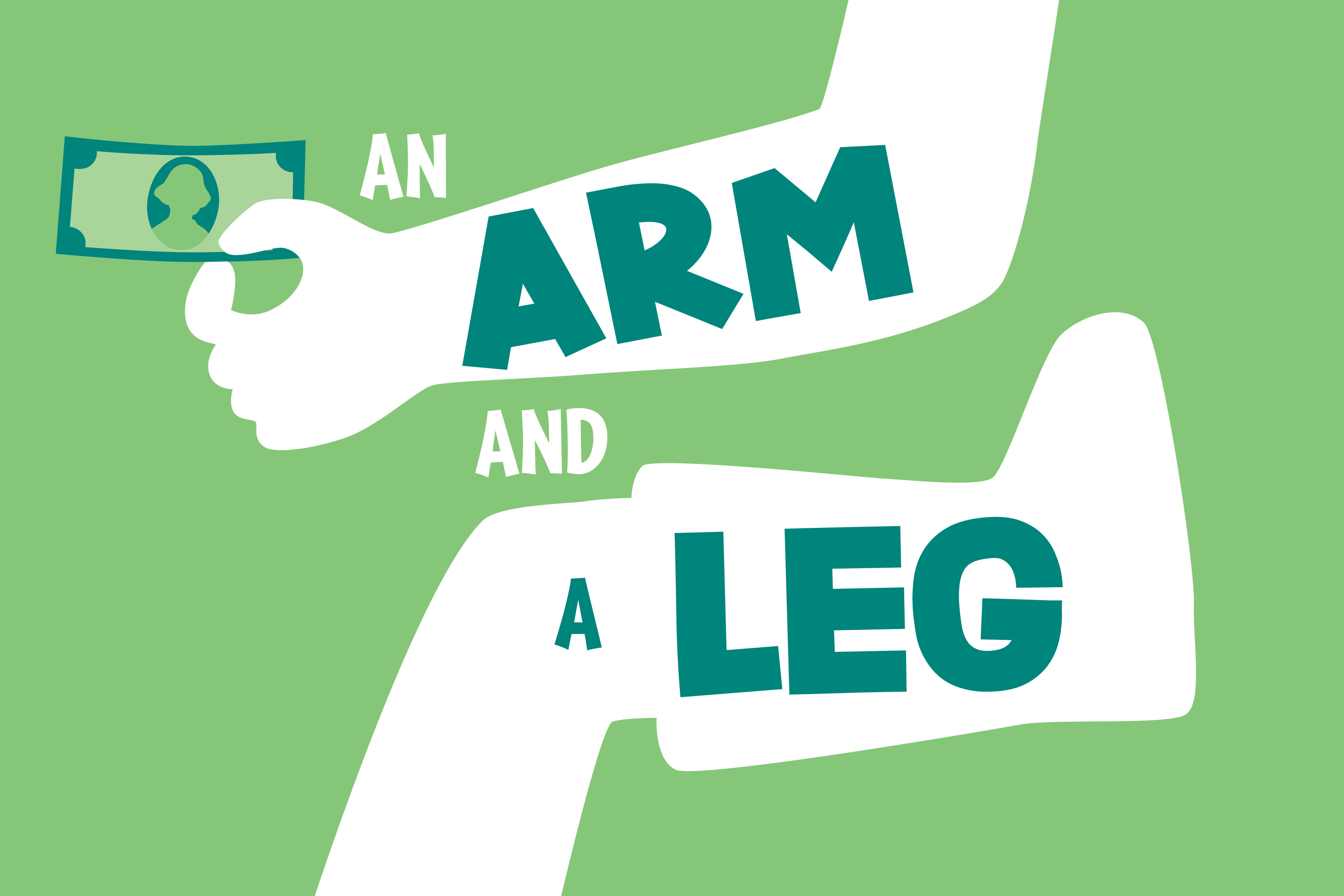

Dan: This is An Arm and a Leg. A show about why health care costs so freaking much, and what we can maybe do about it. I’m Dan Weissmann. I’m a reporter, and I like a challenge. So the job we’ve chosen on this show is to take one of the most enraging, terrifying, depressing parts of American life, and bring you something entertaining, empowering, and useful.

The Shkreli Awards show is a countdown, starting with number ten. And they started with a doozy this year.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony):Number ten. Texas Medical School allegedly neglects to notify next of kin before selling body parts of the deceased.

Dan: NBC News reported that the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Forth Worth was getting unclaimed bodies from the county coroner, and then cutting them up and selling them — without getting anybody’s consent.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): The center’s business supplied the body parts to major for-profit ventures like Medtronic and Johnson Johnson. The investigation found repeated failures at the center and at the county level to contact family members who were, in fact, relatively easy to identify and reach.

Dan: For instance, NBC talked with the family of Carl Honey, a veteran who died homeless, but was entitled to a military burial. Here’s what happened instead.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Swedish medical device maker paid 341 dollars for Honey’s right leg. A Pittsburgh medical education company spent 900 dollars for his torso, and the U.S. Army paid 210 dollars for bones from his skull. It just sounds so macabre. It’s more like a Halloween story.

Dan: When NBC News told the university what they’d found — and that they’d be publishing their findings — the medical school shut down the program and fired the people who had been running it.

But as Vikas Saini reflected when we talked, this probably wasn’t a story about a few rogue administrators. It sounded to him more like a really grisly example of how health care institutions get run.

Vikas Saini: They set a tone at the top, that’s, we got to make our numbers. We got to make our bottom line. You know, it’s like the widget factory and, you know, how many cars did Tesla ship, and with that mentality, you set the tone.

Once you set the tone, you can’t keep track of what everybody’s doing. And the people probably thought they were doing the right thing. They’re trying to bring in some revenue.

Dan: If your job is to bring in revenue, help make the numbers, then why would you bother trying to contact next of kin and get consent before selling off somebody’s body parts?

And this was a state medical school. As we’ll see, as you know, this theme — gotta make our numbers — runs through the whole awards ceremony and through so much of health care.

Next on the list was another banger.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Number nine, out of the mouths of babes, a taste for tongue-tie cutting intensifies.

Dan: I’d never heard of this, but: In some infants the little bit of tissue that connects the tongue to the floor of the mouth is a little thicker, or shorter, and that’s called a tongue tie. The New York Times reported that lactation consultants have sometimes advised new moms to have tongue-tied babies snipped, to help with nursing.

And the Times reported that the procedure has exploded in popularity.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Despite a lack of evidence showing effectiveness, baby tongue tie cutting procedures are being touted as a cure for everything from breastfeeding difficulties to sleep apnea, scoliosis, and even constipation.

Dan: New York Times reporters talked to one doc who said he does this procedure a hundred times a week. At 900 dollars a pop.

Dentists also do a lot of these, and a medical-device maker named Biolase apparently was encouraging them to do more. Here’s Dr. Saini from the awards ceremony again.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): At an April 2024 event for pediatric dentists billed as tequila and tongue ties, representatives for the laser device company trained attendees on the procedure before doing rounds of tequila shots and margaritas.

I should add that, you know, they had a third annual Phrenectomy Fiesta, which was advertised as “nacho average dental meeting.”

Dan: Later, Vikas Saini told me this story actually stirred some deep reflection, that goes back to the Lown Institute’s origin story, and his own.

The institute started as the Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, founded in 1973 by Dr. Bernard Lown, a cardiologist who advocated for non-invasive management of heart disease — and who became Saini’s mentor.

Vikas Saini: Dr. Lown’s motto was we do as much as possible for the patient and as little as possible to the patient.

Dan: Saini appreciates how doctors and researchers want to discover new things. But in our system, that desire gets wrapped up in the medical industry’s need to make the numbers — find new products to sell — like procedures.

Vikas Saini: These procedures take off, especially if there’s a need or a plausible facsimile of a need in this case. And once they take off, you know, it sort of snowballs.

Dan: Tongue-tie cutting looks to him like an especially wild version of the product-development side of things. And an event like tequila and tongue ties just strikes him as a natural extension.

Vikas Saini: This idea that the manufacturers train people in the technique, that’s not confined to this. This goes on all over the place.

Dan: We could dig up probably a trove of tongue ties and tequila shots-like events.

Vikas Saini: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Gallbladders and gimlets.

Dan: Here’s another example of a product in search of a market. This story was dug up by Arthur Allen, a reporter with our pals at KFF Health News. And in this case, the product is a drug.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): A drug company pursues high dose of profits despite risk to patients. That’s shocking. Amgen’s lung cancer drug, Lumakras … How do they make these names? Lumakras? There’s Ludacris. Lumakras… was granted accelerated FDA approval in 2021 at a daily dose of 960 milligrams.

Dan: But the company also had to test a lower dose: 240 milligrams. Which turns out to work just about as well, with a lot fewer side effects.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): That should be good news for patients looking to reduce the diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and mouth sores that can occur.

Dan: One patient told KFF Health News, “After two months on that drug, I had lost 15 pounds, had sores in my mouth and down my throat, stomach stuff. It was horrible.”

So yeah, a lower dose sounds like great news.

But not for Amgen. KFF Health News reported that by selling the higher dose, the company makes an extra 180 thousand dollars per year, per patient. So that’s what they’re doing.

At the awards ceremony, Vikas Saini said the story shows weaknesses in the FDA approval process. It’s long and expensive, but it’s not comprehensive.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): There’s no way of holistically looking at how much does this cost? What are the side effects? What are the trade-offs? And what’s the strength of the evidence? We need different mechanisms and methods than just saying, “Hey, you’re approved. You can charge a thousand bucks and we’ll figure it out later.”

Dan: Before giving “final approval,” the FDA has asked Amgen for extra studies, but meanwhile, the drug is on the market, and the “FDA-approved” dose on the label is … the higher one.

So, we’ve heard about procedures and drugs getting pushed that may… not be the best for patients. But do make money. And then there’s a story from the New York Times about folks selling products that … don’t seem to even exist.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Here’s a story that’s gonna piss people off, perhaps. In 2023, a massive surge in Medicare billing for urinary catheters left patients shaking their heads. Up to 450,000 beneficiaries had bills for catheters submitted on their behalf.

Representing an 800 percent increase over previous years. Just seven suppliers were responsible for two billion dollars of these suspicious charges.

Dan: That two billion dollars? The New York Times story says that could amount to a fifth of all Medicare spending on medical supplies for that year. That’s just seven “suppliers.”

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): When the New York Times looked into these suppliers, the curiously named Pretty in Pink Boutique, they found no medical business at its address, and its phone number rang a random auto body shop.

Dan: The Times found that Pretty In Pink had billed Medicare for more than a quarter-billion dollars. I said to Saini: This example seems to show, this kind of fraud — maybe you don’t even have to try that hard.

Vikas Saini: I think it just illustrates, you know, the dollar flows through healthcare are so massive. Multiple trillions of dollars. You know, that a billion here, a billion there, it’s not even real money yet.

Dan: So, with trillions of dollars moving around, and a LOT of people who need to hit their numbers, we get high-priced drugs that may not be worth the money and body parts sold off without anybody’s consent. Folks getting procedures they may not need. Companies billing for catheters no one seems to have gotten.

And of course the Shkreli Awards “honored” more winners. Including a doctor accused of giving patients drugs they didn’t need — and which killed them.

There was an insurance company that denied a claim for an air-ambulance ride for a baby — leaving the family on the hook for more than 97 thousand dollars. [That’s another one reported by our pals at KFF Health News, with NPR this time.]

And there were two stories about hospitals beholden to private equity investors. One has been accused of denying care to cancer patients and demanding payment upfront.

The hospital denies that allegation, but NBC News found that their charity care policy had been altered in 2023 to exclude cancer treatment.

And as bad and ridiculous as all this sounds, still ahead, we’ve got top two honorees – well, dis-honorees — and some bigger thoughts from Vikas Saini about what it all means. That’s right after this.

An Arm and a Leg is a co-production of Public Road Productions and KFF Health News — that’s a nonprofit newsroom covering health issues in America. KFF’s reporters do amazing work — they’ve broken lots of Shkreli Award winning stories. I’m honored to work with them.

The other private-equity story in this year’s Shkreli Awards involves a chain of hospitals, Steward Healthcare, that ended up bankrupt. The Boston Globe published a heartbreaking story with the headline, “They died in hallways. In line. Alone. Their deaths are the human cost of Steward’s financial neglect.”

The Shkreli Awards gave their number one spot to Steward’s CEO — well, now he’s the former CEO: Ralph de la Torre, who reportedly made a quarter-billion dollars over the four years leading up to the bankruptcy.

They illustrated the story with a photo of an empty chair with a name card for de la Torre — in a Congressional hearing room. He skipped the hearing — he was reportedly on one of his yachts at the time. And got held in contempt.

It’s a hell of a story. But if I had gotten to vote for the top spot, I would’ve gone with the company that became the runner up.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): Number two, corporate healthcare behemoth exercises crushing power. So what started out as a small Minnesota health insurer is now the fourth largest business in the nation by revenue, controlling nearly 90,000 physicians and acquiring influence across the breadth and depth of the healthcare industry in the United States.

Dan: Ninety-thousand physicians. That’s more than three times as many doctors as work for the VA.

Of course that company is UnitedHealth Group. Which also operates the country’s biggest insurance company, United HealthCare. And a BUNCH of other health care businesses. We’ve talked a lot about United on this show in the last couple of years.

And a team at STAT News — that’s a news outlet covering health, medicine and science — they did a massive series on United in 2024, documenting just how big United has grown, and how its tentacles interact.

For instance: UnitedHealth is the biggest player in Medicare Advantage — that’s the privatized version of Medicare. You’re in a United Healthcare Medicare Advantage plan, your in-network doctor is likely to work for United HealthGroup.

STAT interviewed some of those doctors, who said they felt pressured to, one, spend less time with patients. And two … well, the second part needs a little setup: When you run a Medicare Advantage plan, you get extra money— a bonus — for insuring patients who are less healthy.

So the second thing these docs told STAT was: They felt pressured to use aggressive medical-coding tactics to make their patients look as unhealthy as possible. Which could earn that bonus for the insurance plan.

Vikas Saini (awards ceremony): According to STAT this tactic may have allowed the company to take tens of billions of dollars in additional payments from us, the taxpayers, over the past decade. UnitedHealth faces a federal lawsuit for this behavior, as well as an ongoing antitrust investigation. And of course, the company denies any wrongdoing.

Dan: When we talked, Vikas Saini said: If he were working for United, he might pursue the same kinds of strategies. That’s how you hit your numbers, keep shareholders happy. It’s the logic of so much of our healthcare system.

It was the logic of Martin Shkreli, the guy who gives these awards their name. Shkreli did eventually spend seven years in jail. But not for jacking up the price of medicine.

Vikas Saini: People say he went to jail and they link it to the pharma pricing thing, but he didn’t go to jail for that. He went to jail for this other thing, securities fraud. So it may be, raising the price that much was perfectly legal, and then that puts a different spin on his justification, which is he felt it was his duty to his shareholders to maximize what he could make.

Dan: By the same logic, United owes its shareholders maximum return. Grows bigger and bigger. And other players — trying to hit their numbers — they try to grow big enough to compete.

Vikas Saini: Now, maybe someday, you know, we’ll have three behemoths duking it out. But again, the people left holding the bag and all these healthcare Godzilla-versus-King-Kong fights, the people left holding the bag are patients, communities, smaller hospitals, rural hospitals, and most of us, really.

Dan: When Godzilla and King Kong fight, they stomp on everybody.

Vikas Saini: Yeah, exactly.

Dan: Meanwhile, United has been in the news recently, in a big way. In December, the CEO of the insurance division, Brian Thompson, was shot to death in New York. You probably heard about it.

Vikas Saini: I’d characterize my mood, or my reaction in response to that shooting to be one of alarm and urgency. The urgency is that we’ve been doing the Shkreli Awards for, you know, years, and years, and years. You know, the kind of anger and the kind of simmering resentments, they have been there for a while. And that’s what I’m alarmed about. Because we got big problems. If nothing else, it’s a flare being shot up to say there is a crisis and to call it anything less than a crisis is not real.

Dan: Vikas Saini sees this crisis as an extension of how our health care system works. Everybody hitting their numbers. And he asks, “Yeah, but, numbers of what?”

Vikas Saini: If we’re going to treat health care as a commodity and we’re going to have the magic of the marketplace solve all these problems, which some people still think is the way forward – I happen to disagree in many dimensions – but according to the logic of the marketplace, what’s the product off the assembly line? If the product is health care activity, health care procedures, then we have the system we have, but what if the product were health? What if the product were wellness?

Dan: We don’t measure for that. He thinks again about his mentor, Bernard Lown.

Vikas Saini: He was always fond of saying that in most other businesses, the you get more efficient by doing everything faster. And he said, in health care, at least in the doctor patient relationship, you get more efficient by doing everything slower.

Dan: Meaning, by taking time to really get to know patients.

Vikas Saini: The quick example is, if I know someone for 10 years and they come in Friday at 4:30 with a headache, I have one response. If I’ve never met this person in my life and they come in Friday at 4:30 with a headache, I’m more likely to send them for a CT scan or see a neurologist or whatever the hell it is.

Dan: In addition — and contrast — to the Shkreli Awards, the Lown Institute gives out a Bernard Lown Award for Social Responsibility.

It honors a “young clinician” — under the age of 45– who stands out for “bold leadership” in humanitarian work and standing up for justice.

If you know somebody who could be a match, the deadline to nominate them for the 2025 award is January 31.

Speaking of deadlines, we had a big one on December 31: The end of our year-end fundraising drive.

We were racing to hit a big target: Between the Institute for Nonprofit News and a few super-generous donors, there were funds to match 30 thousand dollars in gifts.

Did we make it?

You bet we did. Or should I say, YOU did. Thank you SO much. Because of your generosity and commitment, we’re starting out 2025 super-strong.

Starting with: We’re bringing back the First Aid Kit newsletter, and making it WEEKLY. Starting in February. I’m super-excited.

Meanwhile, we’re starting an extremely cool partnership with KUOW, Seattle’s NPR news station. They’ll be helping more people discover this show– as a podcast.

(No immediate plans for a broadcast version, but this is really big. In just in the first few days, we are seeing lots of new folks listening to An Arm and a Leg — and we’re literally just getting started.)

If you’re one of the folks who’s discovered this show with help from KUOW and the NPR network, welcome aboard! I’m so glad you’re here.

We’ll be back with a new episode in a few weeks, and meanwhile, feel free to dig around in the hundred-and-some episodes we’ve published in the last six years. I think they’re all pretty good.

Catch you soon.

Till then, take care of yourself.

This episode of An Arm and a Leg was produced by me, Dan Weissmann, with

help from Emily Pisacreta and Claire Davenport — and edited by Ellen Weiss.

Adam Raymonda is our audio wizard.

Our music is by Dave Weiner and Blue Dot Sessions.

Bea Bosco is our consulting director of operations.

Lynne Johnson is our operations manager.

An Arm and a Leg is produced in partnership with KFF Health News. That’s a

national newsroom producing in-depth journalism about health issues in

America and a core program at KFF, an independent source of health policy

research, polling, and journalism.

Zach Dyer is senior audio producer at KFF Health News. He’s editorial liaison to this show.

And thanks to the Institute for Nonprofit News for serving as our fiscal sponsor.

They allow us to accept tax-exempt donations. You can learn more about INN at

INN.org.

Finally, thank you to everybody who supports this show financially.

You can join in any time at arm and a leg show, dot com, slash: support.

And here are the names of just some of the people who pitched in before the end of 2024. Thanks this time to… [names redacted]

Richard Clark has been clean and sober since September 1980 and has always been open about his atheism. He became involved in AA because of the compassion of an old-timer who was a devout Christian. Richard is now sober 44 years with no relapses, active in his weekly agnostic meeting, and never conceals his atheism. Professionally, Richard has been a therapist in addictions work since 1985. For several decades he’s been committed to the ancient Buddhist stream of Arhat consciousness and been recognized as a Pratyeka-buddha, pre-Theravada practise (and still working at it). He offers private counselling sessions with clients from across Canada. He has written three books and is presently writing a fourth book for addiction counsellors… and plans a fifth book on the psychology of recovery in Buddhism (atheist version). There is more information about him at

Richard Clark has been clean and sober since September 1980 and has always been open about his atheism. He became involved in AA because of the compassion of an old-timer who was a devout Christian. Richard is now sober 44 years with no relapses, active in his weekly agnostic meeting, and never conceals his atheism. Professionally, Richard has been a therapist in addictions work since 1985. For several decades he’s been committed to the ancient Buddhist stream of Arhat consciousness and been recognized as a Pratyeka-buddha, pre-Theravada practise (and still working at it). He offers private counselling sessions with clients from across Canada. He has written three books and is presently writing a fourth book for addiction counsellors… and plans a fifth book on the psychology of recovery in Buddhism (atheist version). There is more information about him at