This post was originally published on this site

By Brendan O’K

“All people must necessarily rally to the call of their own particular convictions and we of AA are no exception,” said Bill Wilson. One of my strong convictions is agnosticism, the belief that nobody knows or can know of the existence or nature of God. So I lack the religious faith that so many people told me was essential to thrive in AA. But after 15 years I’m still involved in our movement: I go to two or three meetings a week (five in the Zoom/Covid period) and am a volunteer for the AA telephone helpline in London.

Although I’ve lived in London for many years, I grew up mostly in Liverpool in the northwest of England, a city unusual for its high number of Catholics – many, like me, of Irish descent. I was an altar boy, a choirboy at the Catholic cathedral and around the age of 17 was being considered by my Jesuit educators as a potential priest. I had what I thought was a deep faith and I sincerely thought (agonised) about being a priest. But my faith turned out to be brittle and just an adolescent passion – maybe I read too many books (Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov was a big influence) – and by the time I was 18, 19 I had lost any interest in religion.

I mention this part of my background to show that my attitude to religion isn’t one of “contempt prior to investigation” as the Big Book says of some people – in fact, I know well the religious impulses and feelings, having once experienced them. Incidentally I think people who lapse from their faith often throw themselves into political activism of various kinds to replace what they sense they’ve lost, but that’s not for me.

At university in Manchester, I started drinking regularly. At first it was normal, social drinking, based on parties, girls, friends, the usual things for young men. In my 30s I became more melancholy after various heartbreaks with women and started drinking heavily, often alone. By the time I was 44 I was drinking mechanically, like a robot, and it was now an empty experience. That included my last day of heavy drinking, which was, on the surface, spectacular.

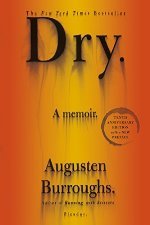

I was staying with friends in New York and on July 4th, 2005, Independence Day, I went to watch baseball in the Bronx for over four hours (of steady drinking), then headed to Battery Park in Manhattan to see James Brown perform, followed by two parties in Brooklyn where I consumed four bottles of red wine, topped off by sleeping with a married woman. The following day, hungover and remorseful, I bought some books including a novel called Dry, by Augusten Burroughs, about a man who is forced to go to AA, hates it, then gradually likes it as he experiences the benefits of sobriety. I read this on the plane back to London a few days later and it planted a seed.

I was staying with friends in New York and on July 4th, 2005, Independence Day, I went to watch baseball in the Bronx for over four hours (of steady drinking), then headed to Battery Park in Manhattan to see James Brown perform, followed by two parties in Brooklyn where I consumed four bottles of red wine, topped off by sleeping with a married woman. The following day, hungover and remorseful, I bought some books including a novel called Dry, by Augusten Burroughs, about a man who is forced to go to AA, hates it, then gradually likes it as he experiences the benefits of sobriety. I read this on the plane back to London a few days later and it planted a seed.

A few weeks on, with all the elation of drinking gone, I turned to AA in desperation. On the one hand, I had misgivings about the religious nature of most people in the programme (this is the nature of AA even in a huge, otherwise largely secular city like London.) This was in stark contrast to my non-AA life, where almost everyone I knew had grown up secular or was a lapsed Jew, Muslim, Anglican or Catholic like me. But on the other hand, after a single meeting I completely lost the desire to drink, and I decided to keep coming back. I will always be grateful to AA for changing my life for the better.

I took on commitments and got a sponsor. I was enthusiastic. But I was always aware of most people’s casual assumption that there is a god, and found it hard to adopt a belief in a higher power helping me towards sobriety. Like many in this position, I settled upon AA itself as my higher power – I mean the members who had empathy with me and who were helping me. After five or six years of this, having done the 12 Steps and become a sponsor for people (who were mostly agnostics and atheists), I realised I was mostly enduring the religiosity of our movement and wasn’t always getting what I needed to thrive. I was too often sitting silently at the back of the room, trying to tolerate what was – to me and a minority of other AA members – sometimes nonsense. I felt present but not involved, like the lapsed Catholic I am who goes to mass once a year with his dad at Christmas but who doesn’t take communion.

I think being in AA should include having a strategy for sharing my own ‘strength, hope and experience’ in meetings, even when the topic being discussed is God. It isn’t productive to angrily challenge what is being said by others in the meeting, and yet there is more to our sobriety and more to Alcoholics Anonymous than merely learning how to blend in. Some of you may know the despair that can accompany having to choose between pretending to fit in and being ostracised by the people around you.

So, with a friend, I revived the mini-tradition in London of meetings for agnostics, atheists and ‘freethinkers’ by setting up meetings for such people in north and east London. They are still flourishing and new ones which are nothing to do with me have also now formed in different parts of the city. In 2018 the General Service Conference of AA in North America voted to adopt the British conference-approved pamphlet, “The God Word: Agnostics & Atheists in AA.” It was translated into French and Spanish from the original English. I’m proud to say this pamphlet, which is now eligible for AA meetings all over the world, was largely the work of the small group I helped to set up in Islington, north London on Thursday nights. We lobbied AA for a few years about it and eventually won.

In our meeting formats and in our general tone we try to be accepting, encouraging and supportive of anyone looking for a solution to their alcoholism irrespective of what they believe or don’t believe. There is no shortage of newcomers coming to our meetings.

But I also attend ‘mainstream’ meetings, where most people seem to believe in a god. Some are dogmatic about this (a minority – there are also, of course, dogmatic atheists who won’t engage in a dialogue with those who don’t share their views), but most people are friendly to me and accept that I’m secular. Occasionally I’m told point-blank by a religious fundamentalist that if I don’t find God as my higher power I’ll eventually get drunk. I just graciously decline their offer to help me. I’m strong and secure in my agnosticism and will not be marginalised. They have their opinion, I have mine, there’s no need for me to respond angrily. I sometimes point out that the AA headquarters in England (in York) completely accepts the legitimacy of the secular meetings we have set up. I’m strong and secure in my agnosticism. Nobody is going to marginalise me. We’re all in this together, all recovering alcoholics who face similar daily challenges of living a sober way of life.

Frankly, for 15 years I’ve seen AA sometimes – often – being ineffective even for those who strongly believe in a traditional god. This is probably due to the large amount of mystification that usually comes with AA’s message. The difficult parts of our process of sobriety, such as the unruly will, the unmanageable life, the dilemma of our powerlessness and our residual character defects are just ‘turned over’ to a supposedly loving god (a god who it seems chooses to make some alcoholics sober and leave others to carry on drinking ruinously.)

I thoroughly accepted Step 1, I surrendered. This broke the vicious cycle that happened when my own ideas about correcting a bad situation only made things worse. But ultimately, even believers need a more precise understanding of the solution than “Let go and let God.”

AA, I suggest, can sometimes benefit from greater clarity regarding down-to-earth strategies. For many, belief in God is a catalyst in a process that makes sobriety possible, but the process itself is all about tapping into “human power.”

Viewing AA’s solution as “God doing for us what we could not do for ourselves” is to accept magical thinking. I can’t accept it (not in an arrogant way, I hope. ) More relevant to me is the empathy one gets at AA meetings, the actions taken under the 12 Steps, the social co-operation. This is all the work of “human power,’ ordinary people. It has nothing to do with a supernatural entity. All the resources necessary for sobriety are already in the possession of men and women.

If for you God is the answer to helping you get sober, that’s fine by me, and in fact none of my business anyway. But for me and for so many others the most important and salient assets AA has are in-depth identification, a sense of community, pragmatic wisdom about addiction, and sometimes just having something to do something that doesn’t involve using alcohol or drugs.

I’m not really interested in religion, I’m not even that interested in ‘spirituality’ – I don’t really know what that word means, I never have, even when I was a teenage Catholic. I just want to keep up this sober life which most of the time gives me peace of mind. I’m in AA for the same reason as you are, whether or not you have religion.

I hope a time will come when non-believers aren’t a sub-group that is grudgingly tolerated but instead are regarded as people who show AA is more concerned about being properly effective than about preserving AA orthodoxy.

The best way to make people realise that us non-believers aren’t working against AA or practising Satanic animal sacrifices at night is to share a positive message of recovery that everyone can relate to; to share one’s experience, strength and hope in a manner that invites an empathetic understanding of how atheists and agnostics experience AA; to form friendships where you can, focusing on similarities and responding to differences graciously; to always assume that there is someone in the meeting who needs to hear that they are not the only one who feels the way they do; to do service at meeting level and perhaps beyond; reach out to newcomers of the same gender, simply reassuring them they’re not alone; embody an attractive version of recovery, remembering the phrase ‘attraction, not promotion.’ Use humour, if you’re good at that. This puts people at ease, especially self-deprecating humour.

Finally, let’s suppose the word ‘spirituality’ is meaningful. I discovered that my addiction wasn’t a by-product of alcohol abuse, it was ‘a false filling-up of spiritual emptiness.’ It was ‘a set of protective repetitions designed to eliminate difficult feelings and choices.’ (I’m quoting a writer friend of mine who wrote a very good book about heroin and alcohol addition.) My friend continues: “If it is a disease of More, then at last I am Enough. I’ve stopped taking life so personally. I’m not so plagued by shame and self-hate.’ What he really wanted in his years of drugging and drinking, he now realises – and I realise too – was connection and love. I’ve had those two things in AA, with both non-believers and religionists. I hope you get some too.

Brendan O’K is 59 and has been sober since July 23rd, 2005. As an agnostic, he found the Steps difficult to accept at times but did them with a sponsor all the same. Having adopted a more open-minded stance to things he disagreed with, he now felt able to get involved in establishing meetings for other agnostics, atheists and freethinkers in London, having seen many newcomers give up because of the programme’s religiosity. Once these meetings were up and running and providing support for fellow sceptics, he found he had got his resentments against AA off his chest and took part in both mainstream and secular meetings. Brendan wants to put back something of what was freely given to him by AA.

The post An Agnostic and Mainstream AA first appeared on AA Agnostica.