This post was originally published on this site

Soon after a series of state laws left a Planned Parenthood clinic in Columbia, Missouri, unable to provide abortions in 2018, it shipped some of its equipment to states where abortion remained accessible.

Recovery chairs, surgical equipment, and lighting from the Missouri clinic — all expensive and perfectly good — could still be useful to other health centers run by the same affiliate, Planned Parenthood Great Plains, in its three other states. Much of it went to Oklahoma, where the organization was expanding, CEO Emily Wales said.

When Oklahoma banned abortion a few years later, it was time for that equipment to move again. Some likely ended up in Kansas, Wales said, where her group has opened two new clinics within just over two years because abortion access there is protected in the state constitution — and demand is soaring.

Her Kansas clinics regularly see patients from Texas, Missouri, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and even Louisiana, as Kansas is now the nearest place to get a legal abortion for many people in the southern U.S.

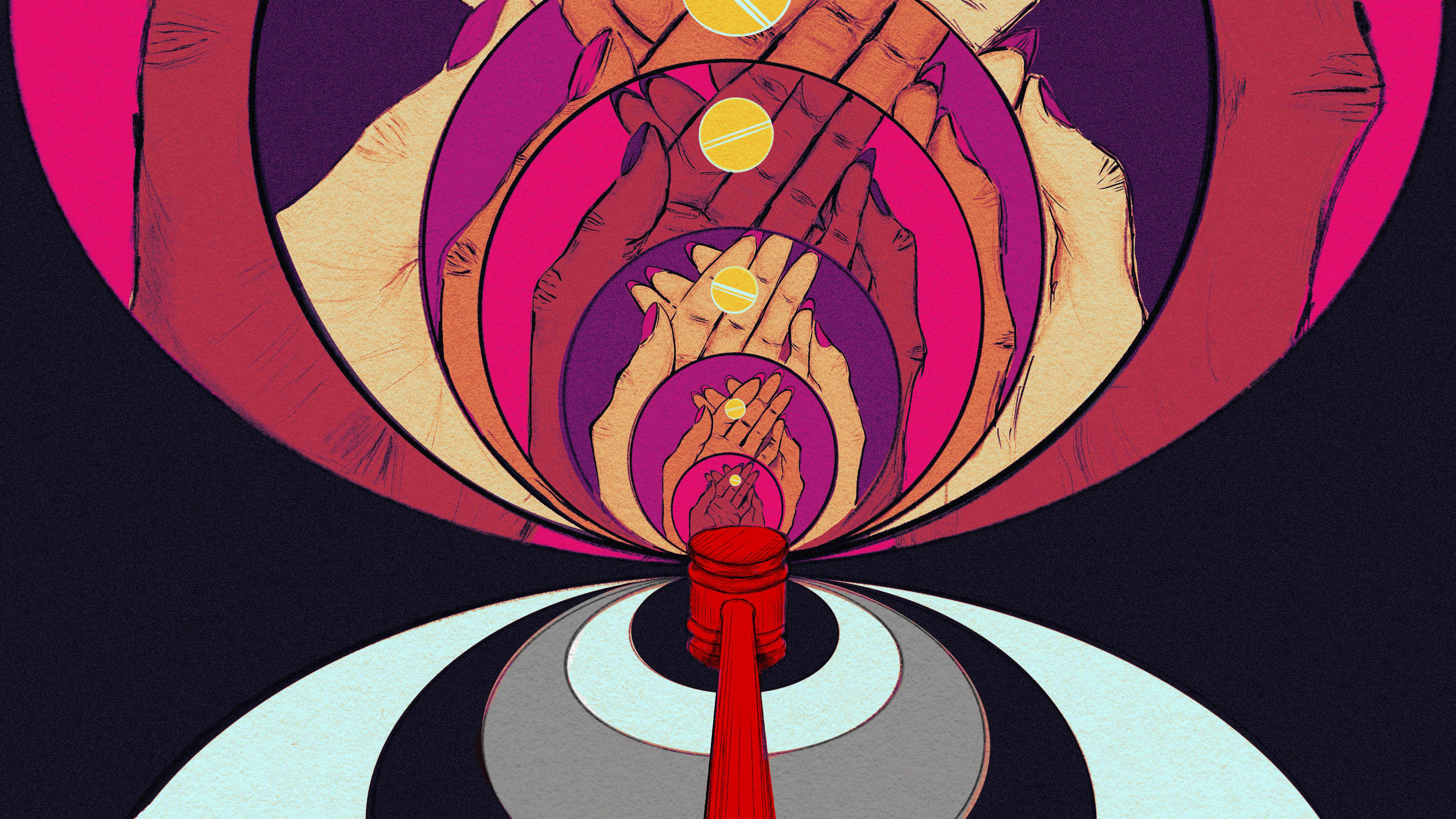

Like the shuffling of equipment, America’s abortion patients are traveling around the nation to navigate the patchwork of laws created by the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which left policies on abortion to the states.

Since that ruling, 14 states have enacted bans with few exceptions, while other states have limited access. But states that do not have an abortion ban in place have seen an 11% increase in clinician-provided abortions since 2020, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a national nonprofit that supports abortion rights. Over 170,000 people traveled out of their own state to receive abortion care in 2023, according to the institute.

Not all of the increase in abortions comes from interstate travel. Telehealth has made medication abortions easier to obtain without traveling. The number of self-managed abortions, including those done with the medication mifepristone, has risen.

And Guttmacher data scientist Isaac Maddow-Zimet said the majority of the overall abortion increase in recent years came from in-state residents in places without total bans, as resources expanded to improve access.

“That speaks, in a lot of ways, to the way in which abortion access really wasn’t perfect pre-Dobbs,” Maddow-Zimet said. “There were a lot of obstacles to getting care, and one of the biggest ones was cost.”

Last year, the estimated number of abortions provided in the U.S. rose to over 1 million, the highest number in a decade, according to the institute.

Still, abortion opponents hailed an estimated drop in the procedure in the 14 states with near-total bans.

“It’s encouraging that pro-life states continue to show massive declines in their in-state abortion totals, with a drop of over 200,000 abortions since Dobbs,” Kelsey Pritchard, a spokesperson for Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, wrote in a statement.

Organizations in states where abortion remains legal feel the ripples of every new ban almost instantly. One Planned Parenthood affiliate with a clinic in southern Illinois, for example, reported a roughly 10% increase in call volume in the two weeks following the enactment of Florida’s six-week abortion ban in May. And an Illinois-based abortion fund, Midwest Access Coalition, experienced a similar pattern the day the Dobbs decision was announced in June 2022.

“Our hotline was insane,” said Alison Dreith, the coalition’s director of strategic partnerships.

People didn’t know what the decision meant for their ability to access abortions, Dreith said, including whether already scheduled appointments would still happen. The coalition helps people travel for abortions throughout 12 Midwestern states, four of which now have total bans with few exceptions.

After serving 800 people in 2021, the Midwest Access Coalition went on to help 1,620 in 2022 and 1,795 in 2023. Some of that increase can be attributed to the natural growth of the organization, which is only about a decade old, Dreith said, but it’s also a testament to its work. It pays for any mode of transportation that will get clients to a clinic, including partnering with another Illinois nonprofit with volunteer pilots who fly patients across state lines on private flights to get abortions.

“We also book and pay for hotel rooms,” Dreith said. “We give cash for food, and for child care.”

The National Network of Abortion Funds, a coalition of groups that offer logistical and financial assistance to people seeking abortions, said donations increased after the Dobbs decision, and its members reported a 39% increase in requests for help in the following year. They financially supported 102,855 people that year, including both in-state and out-of-state patients, but have also seen a “staggering drop off” in donations since then.

Increased awareness about the options for abortion care, spurred on by an increase in news stories about abortion since the Dobbs decision, may have fueled the rise in abortions overall, Maddow-Zimet said.

Both sides now await the next round of policy decisions on abortion, which voters will make in November. Ballot initiatives in at least 10 states could enshrine abortion rights, expanding access to abortions, including in two states with comprehensive bans.

“Lives will be lost with the elimination of laws that protect more than 52,000 unborn children annually,” wrote Pritchard of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, citing an analysis on the group’s website.

In the meantime, Wales said her clinics in Kansas don’t have enough appointments to accommodate everyone who reaches out about scheduling an abortion. In the early days after the Dobbs decision, Wales estimated, only 20% of people who called the clinic were able to schedule an abortion appointment.

The organization has expanded and renovated its facilities across the state, including in Wichita, Overland Park, and Kansas City, Kansas. Its newest clinic opened in August in Pittsburg, just 30 miles from Oklahoma. But even with all that extra capacity, Wales said her group still expects to be able to schedule only just over 50% of people who inquire.

“We’ve done what we can to increase appointments,” Wales said. “But it hasn’t replaced what were many states providing care to their local communities.”

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.