This post was originally published on this site

To discover how millions in opioid settlement funds are being spent in Idaho, you can visit the state attorney general’s website, which hosts 91 documents from state and local entities getting the money.

What you’ll find is a lot of bureaucratese.

Nearly three years ago, these jurisdictions signed an agreement promising annual reports “specifying the activities and amounts” they have funded.

But many of those reports remain difficult, if not impossible, for the average person to decipher.

It’s a scenario playing out in a host of states. As state and local governments begin spending billions in opioid settlement funds, one of the loudest and most frequent questions from the public has been: Where are the dollars going? Victims of the crisis, along with their advocates and public policy experts, have repeatedly called on governments to transparently report how they’re using these funds, which many consider “blood money.”

Last year, KFF Health News published an analysis by Christine Minhee, founder of OpioidSettlementTracker.com, that found 12 states — including Idaho — had made written commitments to publicly report expenditures on 100% of their funds in a way an average person could find and understand. (The other 38 states promised less.)

But there’s a gap between those promises and the follow-through.

This year, KFF Health News and Minhee revisited those 12 states: Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, Idaho, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah. From their reports, it became clear that some did not fulfill their promises. And several just squeaked by, meeting the letter of the law but falling far short of communicating to the public in a clear and meaningful manner.

Take Idaho, for instance. Jurisdictions there completed a standard form showing how much money they spent and how it fell under approved uses of the settlement. Sounds great. But in reality, it reads like this: In fiscal year 2023, the city of Chubbuck spent about $39,000 on Section G, Subsection 9. Public Health District No. 6 spent more than $26,000 on Section B, Subsection 2.

Cracking that code requires a separate document. And even that provides only broad outlines.

G-9 refers to “school-based or youth-focused programs or strategies that have demonstrated effectiveness in preventing drug misuse.” B-2 refers to “the full continuum of care of treatment and recovery services for OUD and any co-occurring SUD/MH conditions,” referring to opioid use disorder and substance use disorder or mental health conditions.

“What does that mean? How exactly are you doing that?” asked Corey Davis, a project director at the Network for Public Health Law, when he first saw the Idaho reports.

Does a school-based program involve hiring mental health counselors or holding a one-time assembly? Does treatment and recovery services mean paying for someone’s rehab or building a new recovery house?

Without details on the organizations receiving the money or descriptions of the projects they’re enacting, it’s impossible to know where the funds are going. It would be similar to saying 20% of your monthly salary goes to food. But does that mean grocery bills, eating out at restaurants, or hiring a cook?

The Idaho attorney general’s office, which oversees the state’s opioid settlement reports, did not respond to requests for comment.

Although Idaho and the other states in this analysis do better than most in having any reports publicly available, Davis said that doesn’t mean they get an automatic gold star.

“I don’t think we should grade them on a curve,” he said. It’s not “a high bar to let the public see at some reasonable level of granularity where their money is going.”

To be sure, many state and local governments are making concerted efforts to be transparent. In fact, seven of the states in this analysis reported 100% of their expenditures in a way that is easy for the public to find and understand. Minnesota’s dashboard and downloadable spreadsheet clearly list projects, such as Renville County’s use of $100,000 to install “a body scanner in our jail to help staff identify and address hidden drugs inside of inmates.” New Jersey’s annual reports include details on how counties awarded funds and how they’re tracking success.

There are also states such as Indiana that didn’t originally promise 100% transparency but are now publishing detailed accounts of their expenditures.

However, there are no national requirements for jurisdictions to report money spent on opioid remediation. In states that have not enacted stricter requirements on their own, the public is left in the dark or forced to rely on ad hoc efforts by advocates and journalists to fill the gap.

Wading Through Reports

When jurisdictions don’t publicly report their spending — or publish reports without meaningful details — the public is robbed of an opportunity to hold elected officials accountable, said Robert Pack, a co-director of East Tennessee State University’s Addiction Science Center and a national expert on addiction issues.

He added: People need to see the names of organizations receiving the money and descriptions of their work to ensure projects are not duplicating efforts or replacing existing funding streams to save money.

“We don’t want to burden the whole thing with too much reporting,” Pack said, acknowledging that small governments run on lean budgets and staff. But organizations typically submit a proposal or project description before governments give them money. “If the information is all in hand, why wouldn’t they share it?”

Norman Litchfield, a psychiatrist and the director of addiction medicine at St. Luke’s Health System in Idaho, said sharing the information could also foster hope.

“A lot of people simply are just not aware that these funds exist and that these funds are currently being utilized in ways that are helping,” he said. Greater transparency could “help get the message out that treatment works and treatment is available.”

Other states that lacked detail in some of their expenditure reports said further descriptions are available to the public and can be found in other state documents.

In South Carolina, for instance, more information can be found in the meeting minutes of the Opioid Recovery Fund Board, said board chair Eric Bedingfield. He also wrote that, following KFF Health News’ inquiry, staff will create an additional report showing more granular information about the board’s “discretionary subfund” awards.

In Missouri, Department of Mental Health spokesperson Debra Walker said, further project descriptions are available through the state budget process. Anyone with questions is welcome to email the department, she said.

Bottom line: The details are technically publicly available, but finding them could require hours of research and wading through budgetary jargon — not exactly a system friendly to the average person.

Click Ctrl+F

New Hampshire’s efforts to report its expenditures follow a similar pattern.

Local governments control 15% of the state’s funds and report their expenditures in yearly letters posted online. The rest of the state’s settlement funds are controlled by the Department of Health and Human Services, along with an opioid abatement advisory commission and the governor and executive council.

Grant recipients from the larger share explain their projects and the populations they serve on the state’s opioid abatement website. But the reports lack a key detail: how much money each organization received.

To find those dollar figures, people must search through the opioid abatement advisory commission’s meeting minutes, which date back several years, or search the governor and executive council’s meeting agendas for the proposed contracts. Typing in the search term “opioid settlement” brings up no results, so one must try “opioid” instead, surfacing results about opioid settlements as well as federal opioid grants. The only way to tell which results are relevant is by opening the links one by one.

Davis, from the Network for Public Health Law, called the situation an example of “technical compliance.” He said people in recovery, parents who lost their kids to overdose, and others interested in the money “shouldn’t have to go click through the meeting notes and then control-F and look for opioids.”

James Boffetti, New Hampshire’s deputy attorney general, who helps oversee the opioid settlement funds, agreed that “there’s probably better ways” to share the various documents in one place.

“That doesn’t mean they aren’t publicly available and we’re somehow not being transparent,” he said. “We’ve certainly been more than transparent.”

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services said it will be compiling its first comprehensive report on the opioid settlement funds by the end of the year, as laid out in statute.

Where’s the Incentive?

With opioid settlement funds set to flow for another decade-plus, some jurisdictions are still hoping to improve their public reporting.

In Michigan, the state is using some of its opioid settlement money to incentivize local governments to report on their shares. Counties were offered $1,000 to complete a survey about their settlement spending this year, said Laina Stebbins, a spokesperson for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Sixty-four counties participated — more than double the number from last year, when there was no financial incentive.

In Maryland, lawmakers took a different approach. They introduced a bill that required each county to post an annual report detailing the use of its settlement funds and imposed specific timelines for the health department to publish decisions on the state’s share of funds.

But after counties raised concerns about undue administrative burden, the provisions were struck out, said Samuel Rosenberg, a Democrat representing Baltimore who sponsored the House bill.

Lawmakers have now asked the health department to devise a new plan by Dec. 1 to make local governments’ expenditures public.

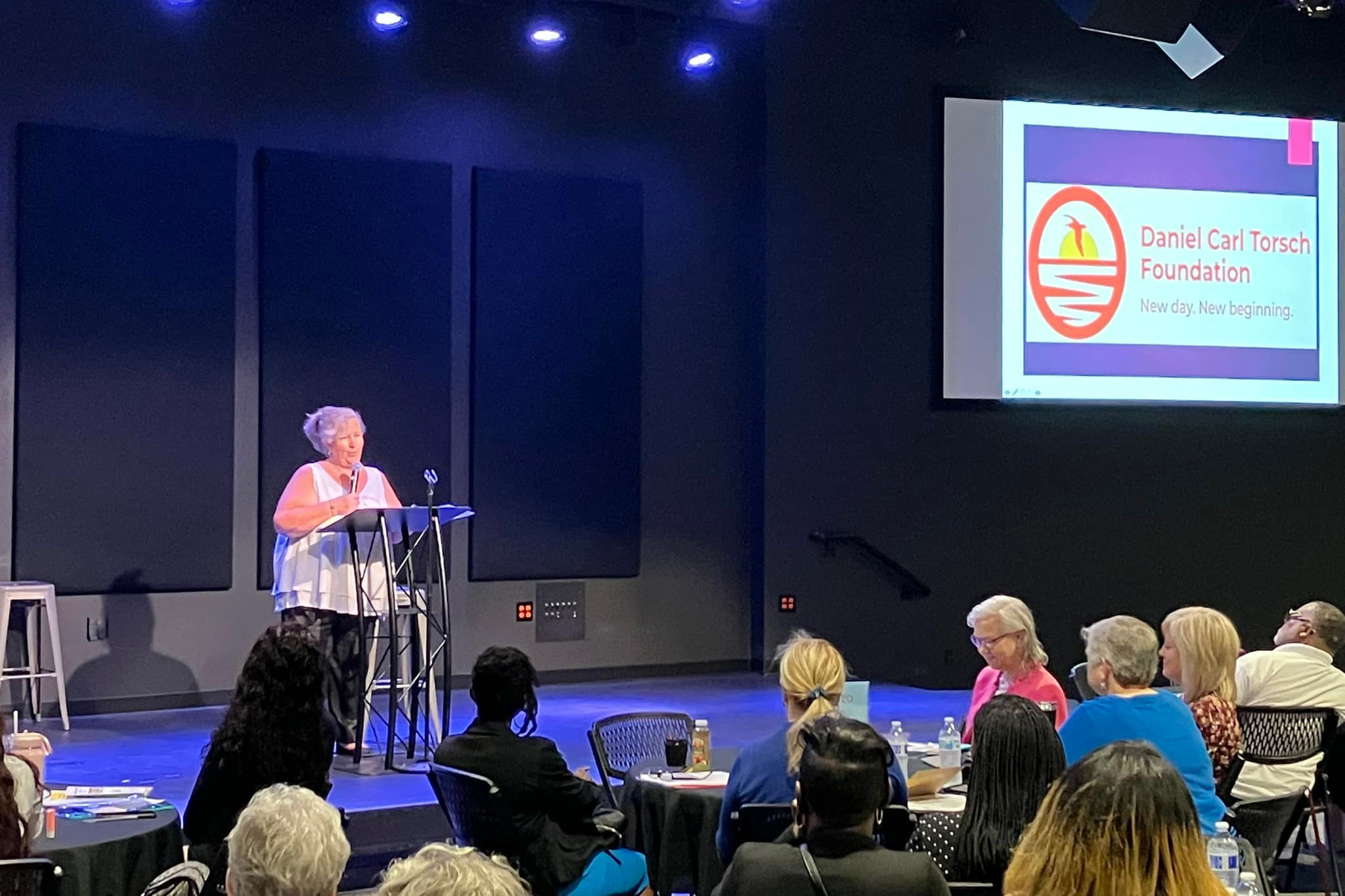

Toni Torsch, a Maryland resident whose son Dan died of an overdose at age 24, said she’ll be watching to ensure the public gets a clear picture of settlement spending.

“This is money we got because people’s lives have been destroyed,” she said. “I don’t want to see that money be misused or fill a budget hole.”

Methodology

In March 2023, KFF Health News published an analysis by Christine Minhee, founder of OpioidSettlementTracker.com, assessing states’ written commitments to report how they use opioid settlement dollars. That analysis determined that 12 states had promised to publicly report expenditures on 100% of their funds in a way an average person could track.

More than a year later, KFF Health News senior correspondent Aneri Pattani and Minhee revisited those 12 states’ reporting practices to determine if they had fulfilled their promises and to assess how useful the resulting expenditure reports were to the public.

Expenditure reports were gathered via state and local government websites, Google searches, and Minhee’s Expenditure Report Tracker. If Minhee and Pattani were unable to find public reports, they contacted state governments directly.

For expenditures to be considered “publicly reported,” they had to meet the following criteria:

1. Expenditures had to be expressed as specific dollar amounts. Descriptions of how the money was used without a dollar figure would not qualify.

2. The report passes the “Googleability test”: Could a typical member of the public reasonably be expected to find expenditure information by keyword-searching online? If people had to file a public records request, navigate lengthy budget or appropriations documents, or rifle through meeting minutes for the information, it would not qualify.

For an expenditure report to be considered “publicly reported with clarity,” it had to meet one additional criterion:

3. Reports had to contain some combination of vendor name (e.g., an individual or organization) that received the money and a description of the money’s use such that a typical member of the public could understand the specific service, product, or effort the money supported.

Each state divides opioid settlement funds into shares controlled by different entities. The majority of expenditures in each share were required to meet the above-listed criteria in order for that share to be classified as “publicly reported” or “publicly reported with clarity.”

For example, in Utah, 50% of opioid settlement funds are controlled by county governments. As of Oct. 9, less than half of all counties had reported expenditures in a manner that was easily accessible to the public. As such, that 50% share was not counted as “publicly reported.”

This analysis was conducted by Pattani and Minhee from July to October. Classifications were made based on states’ expenditure reports as of Oct. 9.

This article was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.